In a less polarized era, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s dire warning that the United States could default on its debts as early as June 1, absent congressional action, might have served as a kick in the pants for lawmakers and the White House to get down to the business of raising the debt ceiling. Instead, Yellen’s announcement on Monday seemed only to entrench the opposing positions of President Joe Biden and congressional Republicans: Biden and Democrats insist that the debt ceiling must be raised without strings attached, while Republicans maintain that any measure to lift the nation’s borrowing cap must be accompanied by spending cuts outlined in a measure recently passed in the House.

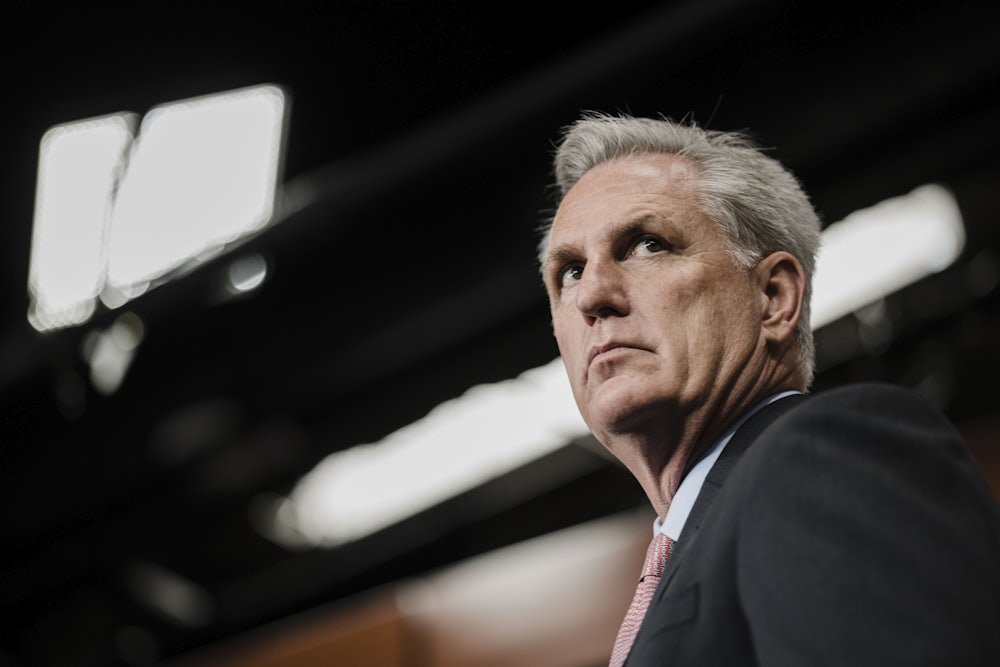

Biden will meet with congressional leaders, including Speaker Kevin McCarthy, next week. But in the meantime, the would-be negotiators are holding firm in their concurrent insistence that the U.S. cannot default and that they will not budge on their respective demands.

“President Biden has refused to do his job—threatening to bumble our nation into its first ever default—and the clock is ticking,” McCarthy said, in response to Yellen’s announcement.

The House narrowly passed legislation raising the debt ceiling last week, marrying it with significant spending cuts that would slash social safety net programs and roll back some of Biden’s signature legislative achievements and priorities. The measure was opposed by four hard-line conservative Republicans, along with all House Democrats. Senate Democrats, however, have dubbed this bill the “Default on America” act—a bit of wordplay that indicates that the measure is dead on arrival in the upper chamber.

“Our position remains the same: Both parties should pass a clean bill to avoid default together, before we hit the critical June 1 deadline,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer told reporters Tuesday. Schumer has started the process of bringing such a bill to the floor, which would suspend the debt ceiling through December 31, 2024—after the 2024 elections. (Where raising the debt limit puts a fixed number on how much the government can borrow, suspending it allows the country to continue borrowing for a specific length of time but hit the ceiling on a certain date.) Schumer also rejected the idea of a short-term hike to extend the period of time for negotiations.

McCarthy has a significant incentive to maintain his position: He underwent 15 grueling votes to obtain his speakership, earned in no small part due to concessions to the far-right flank of the Republican conference. If McCarthy tries to bring forward a clean debt ceiling bill, his leadership could be challenged, threatening his hold on the speaker’s gavel. McCarthy is already walking a political tightrope: Any measure that could obtain Democratic votes would likely lose support from many, if not most, Republicans. Maintaining a firm grip on his caucus may require holding onto Republican demands for as long as possible.

Nevertheless, Senate Democrats agreed that default was not an option—even though it is a distinct possibility. “The question is, when will the Republicans realize that default would be absolutely catastrophic for this country?” argued Senator Gary Peters. “It’s the Republicans that are the ones proposing that. We’re not proposing defaulting.”

The U.S. has teetered perilously close to default before, most recently in a stalemate over raising the limit in 2021. As Congress hurtles toward the “X date”—the day on which the country will no longer be able to fulfill its obligations—it risks significant economic consequences. In 2011, credit agencies downgraded the country’s credit rating for the first time as the U.S. approached default. In that year, House Republicans—emboldened by overwhelming victories in the previous midterm—vowed they would not raise the debt ceiling without extracting some spending cuts. The impasse was temporarily resolved with a deal creating a “supercommittee” to brainstorm ways to cut the deficit, but that effort failed amid partisan disagreements.

The debt ceiling battle this year echoes the fight of 2011, with House Republicans seeking spending cuts in exchange for a debt ceiling hike—although McCarthy has a far smaller majority than former Speaker John Boehner enjoyed. “The fact is, the speaker of the House is in a much weaker position in his conference than John Boehner was 12 years ago,” said Senator Ron Wyden on Tuesday.

But Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, who helped negotiate an end to the impasse with then–Vice President Biden more than a decade ago, said that the conditions had changed. As such, Senate Republicans are leaving negotiations to Biden and House Republicans.

“That was a different set of players than we have today,” McConnell said. “[House Republicans] having achieved an outcome, it should be clear to the administration that the Senate is not a relevant player this time. They have got to have a measure that can pass the House.”

Although any deal will require 10 Republican votes—with Senator Dianne Feinstein absent for an indefinite period, Democrats only hold 50 seats—GOP senators insist that their input is less important than that of their counterparts in the House.

“There’s no point in us moving forward on something that the two of them can’t agree to first,” GOP Senator Kevin Cramer told me. “[Going] second is oftentimes better than the first.”

Still, Senate Democrats argue that the debt ceiling is simply too important to negotiate. “Sometimes there are worthwhile negotiations. Sometimes there are things that are so clearly right and wrong, that you can’t negotiate with a position that is so radical and so extreme,” said Senator Chris Murphy. “This position that they’ve taken is so dangerous for the country that I think we have to convince them to do a clean raise [of] the debt ceiling, and then put off these fights to the budget.”

Senator Jon Tester, a Democrat facing a difficult reelection campaign in Montana, told me that “you don’t negotiate on the debt ceiling,” noting that raising the limit does not incur new debt but rather covers previous spending that has already been allocated. “It’s ridiculous. This is too important to play political games with,” he said. When I asked whether he thinks McCarthy and House Republicans would back down, Tester responded: “I don’t know. Do you think that the guys that McCarthy sold his soul to want to see the economy go into a depression? Because that’s what’s going to happen.”

Another Democrat up for reelection in a ruby-red state has expressed more support for McCarthy’s efforts. Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who has not yet announced his plans for next year, released a statement on Monday urging Biden to “to show true leadership and finally put politics aside and the well-being of our nation first.” Manchin had previously released a statement saying that “Speaker McCarthy did his job and he passed a bill that would prevent default and finally begin to rein in federal spending.”

Most Democrats, however, maintain that the conversation around the debt ceiling should be distinct from the conversation around spending. Democratic Senator Tim Kaine noted that House Republicans have significant leverage over the budget process, meaning that they could negotiate on spending cuts without threatening default. “You don’t have to back down at all, just use your leverage in the right way, not the wrong way,” Kaine said. “Using it to push us to default. Using your leverage to try to get a budget deal that you can vote for, that’s the right way.”

The House is out this week, and the Senate is set to leave town in the last week of May. That leaves little time to reach an agreement; as Tester joked, the deadline is “tomorrow, the day after tomorrow.” House Democrats have launched the process of circumventing McCarthy to bring a clean debt ceiling hike to the House floor; however, that would require five Republican votes, and even moderate Republicans have expressed reluctance to support a so-called “discharge petition.”

When I asked Kaine whether he believed Biden and Democrats would reach a point when they needed to make concessions to House Republicans, the Virginia senator replied: “I don’t know.”

“I’m just really glad they’re having that meeting next week,” Kaine continued.