Jeff Sharlet has spent much of his career talking to strangers and finding authenticity in encounters at typically American way stations on the road. His 2020 book, This Brilliant Darkness, stitches together vignettes of a night-shift worker, a motel boarder, a Cameroonian immigrant, and many others, as he drove from place to place, taking in the mood of the country in the Trump era.

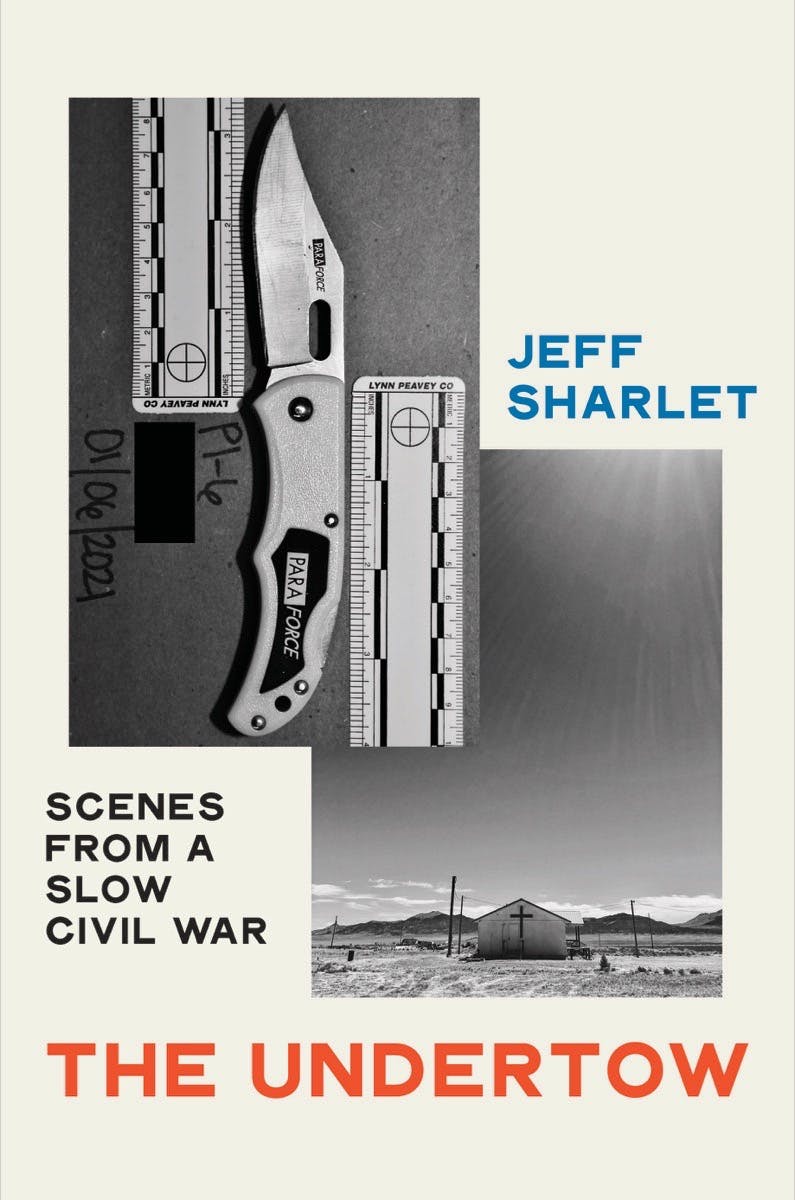

His latest book, The Undertow: Scenes From a Slow Civil War, also takes the form of a road trip, but it is a journey on which he finds fracture rather than connection. From Sacramento to Rifle, Colorado, to Buffalo, New York, at Trump rallies, in bars and diners, and at an International Conference on Men’s Issues, he finds paranoia and unrest. When he visits Vous Church, a hub for televangelism in Miami, he interviews a pastor who proposes they “just stage” the whole conversation. A woman in Sunrise, Florida, tells him she believes their meeting is divinely ordained. And when he tries to understand churchgoers’ views on critical race theory in Omaha, Nebraska, a security guard brings out a man with a gun to threaten him. A theme among his interviewees is dislike of journalists—the “evil media,” as the guard calls it—and a belief that civil war is on the horizon.

The undertow—a current of water that lies just below the surface, pulling in the opposite direction—is Sharlet’s metaphor for the “season of coming apart” that he believes the United States is undergoing. He observes people swept up by the “myths” and the “dreams” of the far right, anxiously relating their premonitions of impending civil war. I recently spoke with Sharlet about his book. During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, we discussed the right’s use of grief and bitterness, the dynamics of the mob, and the future of democracy.

Jasmine Liu: You frame the book—and the road trip across the country that constitutes its backbone—as an attempt to follow Ashli Babbitt’s ghost. What got you interested in her story?

Jeff Sharlet: The book is about grief—and that, to me, is Ashli Babbitt. I remember the minute I saw January 6, I was in the other room; my wife was with our kids sledding. I was texting her as it was happening: “They’re walking toward the Capitol—oh my God, they’re around the Capitol—oh my God, they’re in the Capitol—oh my God, that woman is dead! Oh, it’s a white woman.” And very quickly, we saw the video. I remember thinking, Birth of a Nation, they’re going to tell that story again. Very quickly, they got into Black man kills white woman.

White supremacy feeds on both the perception and the reality of loss. Ashli was this person trying to be a good person, and Donald Trump is that white supremacist saying, it’s OK to be white! It’s OK to be bad! What if you were just pissed? What if you’re in over your head with debt? What if you gave in to the hate? And she did.

J.L.: Why do you see Babbitt as a case of grief and not mourning? What’s the distinction between those two things for you?

J.S.: What happens to unexamined grief is it can become bitterness. There was a men’s rights activist who burned himself to death on the courtroom steps near Keene, New Hampshire, and he was losing a custody battle—as he should have—because he was a violent abuser. That’s curdled grief. He has done something wrong, he has lost a lot for it, that loss is real. The bitterness—for Ashli—it flips into ecstasy, with a kind of mania to it.

J.L.: What do you notice about the right-wing response to her death?

J.S.: What’s interesting is what happened with her husband. Her husband wasn’t really a particular right-winger until she died. And now he is because his wife is dead and he can’t understand it. Now he’s become this really dangerous guy, as she became a dangerous person.

There’s that sentiment of, “Wherever there’s an injustice, I’ll be there! Wherever there’s a guy getting beat up, I’ll be there!” That’s what Ashli Babbitt came to be for the right, and that’s a ghost. They’re embracing a haunting. I don’t think fascism would have accelerated as quickly had it not been for the pandemic and for an inability to process—what a weak word—to mourn together.

J.L.: You’ve been reporting on the right for many years. What struck you about the rallies you reported on for this book?

J.S.: There is this interesting thing of democratization without shape, so it becomes a mob rather than a society or collective. The middle section of the book is called “On Vanity,” and a mob is vanity—it’s the imagination of more agency than you have, and you do this by erasing the complexities of the individual in concert with another. I don’t mean the individual reigns supreme: That’s the old right. The new right is the mob.

J.L.: One of the disturbing things in The Undertow is how basically in every single interaction you’ve had, the far-right activists you meet are totally convinced that we’re accelerating toward civil war. What do you make of this?

J.S.: Even when I started this book, in the spring of 2021, there were historians talking about it, but it was not a reputable thing. Now David French is over here in The New York Times, instead of National Review, writing an op-ed saying civil war, or the “national divorce,” is serious. And underneath, the editorial board is saying, “Holy shit, what DeSantis is doing is serious.” There’s a little bit of “I told you so,” and everybody has been on this for a long time.

A little bit of anger too. The week after the election, there was a bunch of people—I was one of them—saying, this is a slow-motion coup. We were derided for that. It’s like saying, “Do you think there could be violence?” What do you mean, “could?” There already is that.

If you read Kathryn Joyce, she’s understanding all these intellectual rifts within the right. What makes the right a powerful movement now is many tributaries that were once opposed to one another—there was a time when evangelicals would have had nothing to do with Proud Boys—are all like, fucking let’s go, let’s all flow into one another.

J.L.: You note throughout how hostile your interlocutors are about you as a journalist. How did you navigate that aspect of your reporting?

J.S.: I’ve been doing this for a long time. It’s never been like this. In 2016, everybody talked to me. I did tell people I was a writer, and I would be sitting there writing things down. But now everyone’s so excited for the possibility of ferreting out a journalist.

At Trump rallies, if you had a volume meter, attacks on the press get the loudest volume. The weird thing was like—The press, why do you keep going to that pen?

J.L.: I’m curious what you think of this whole genre that really cemented itself during the Trump years, of liberal journalists covering rural Americans who voted for Trump, trying to understand their mentality. Your work in this vein predates the recent surge in this kind of writing and reporting. How do you situate yourself in this new landscape?

J.S.: This is what I’ve been doing for 30 years. I’m not parachuting in, but I’m also not immersing, which is something I’ve done in the past. We’re in the undertow, wherever you are. I use this phrase “We’re in it now.” It’s a little bit of church speak. We’re in it wherever we are. You’re in New York, for instance—there are more Trump voters in New York City than there are people in Vermont.

J.L.: Toward the end of your book, you write, “Democracy is a practice. It may not be real yet, but it is not a dream.” How do you understand that space in between?

J.S.: The fascinating thing to me about the dream

is also the brokenness. You keep trying to imagine this better world. We do not

have a plan right now. I don’t have the solution—this is not a book with

solutions. I dislike those and distrust those.

The last line, which I always knew was going to be the last line of the book—“for a while it was possible not to be scared even”—some people say, “That’s your hope?” Yeah, that’s the hope. The hope is not “We can do it.” There’s no “arc of history bends toward justice.” It doesn’t just do that. Democracy doesn’t just happen.

The noise of democracy is not agreement, isn’t civil, is not a common ground. Tolerance is not like, Hey, I approve of you. Tolerance is like, I fucking hate you, but I’m not going to smash in your door. Tolerance can even include shouting down the speaker. It’s not like, Let’s hear out these thoughts on how people of color have lower IQs—and now you want free speech, you want tolerance. I’m going to say, “Fuck off.” That’s free speech. That’s the democracy I want to have. I don’t think we’ve ever had it.