Take practically any Democratic policy of recent years, and you can find conservatives sounding the same tune. Marco Rubio condemned Biden’s Build Back Better legislation as “Build Back Socialist,” while Glenn Beck deemed his student loan relief program “a socialist failure.” Florida Congressman Matt Gaetz called Biden’s stimulus plan “a Trojan horse for socialism,” while the U.S. Chamber of Commerce said the same thing about the Green New Deal. As the historian David Austin Walsh noted a few years ago, “One of the binding agents holding the conservative coalition together over the course of the past half century has been an opposition to liberalism, socialism, and global communism built on the suspicion, sometimes made explicit, that there’s no real difference among them.” What accounts for the ubiquity of this argument in American political culture?

In their new book, The Big Myth, historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway examine the origins and development of the “quasi-religious” myth of “market fundamentalism.” Focusing on the efforts of business titans, industry groups, and conservative intellectuals over the past century, Oreskes and Conway demonstrate how the belief that markets work best without government interference and that markets, not governments, best guarantee our freedoms, went from fringe to mainstream in American politics and culture. How, they ask, did onetime union leader Ronald Reagan come to sing hosannas to “the magic of the market,” with many Democratic leaders sounding an only slightly less breathless tune?

I recently spoke to Oreskes and Conway over Zoom. During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, we discussed the roots of this ideology, why the “marketplace of ideas” metaphor should be retired once and for all, and whether the fever of market fundamentalism is finally starting to break.

Jack McCordick: What do you think has made market fundamentalist ideology not just palatable, but actively attractive to so much of the American public for so long, given all the ways that it goes against people’s basic material interests?

Naomi Oreskes: There are two important things. One is the power of saturation. If you say something enough times, and you say it in enough different ways, and you recruit spokespeople who seem credible or likable, you can get people to believe things, even when they’re not true. Whether it’s skin creams that will make you young, or a weight loss program that will make you lose weight, people are susceptible to the power of suggestion, and propaganda takes advantage of that.

The other reason why it works is because it appeals to virtues, and particularly it appeals to the virtue of freedom. Americans of all walks of life, all sizes, shapes, and colors, believe in freedom. It’s a deeply held American value. So you tell people a story about how the marketplace is not only magical and has these amazing powers to solve problems, but it also protects your freedom.

J.M.: Recent books on the influence of American billionaires—such as Jane Mayer’s Dark Money and Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains—focus on the last half-century or so. Your book begins much earlier. Why do you start the story in the early twentieth century?

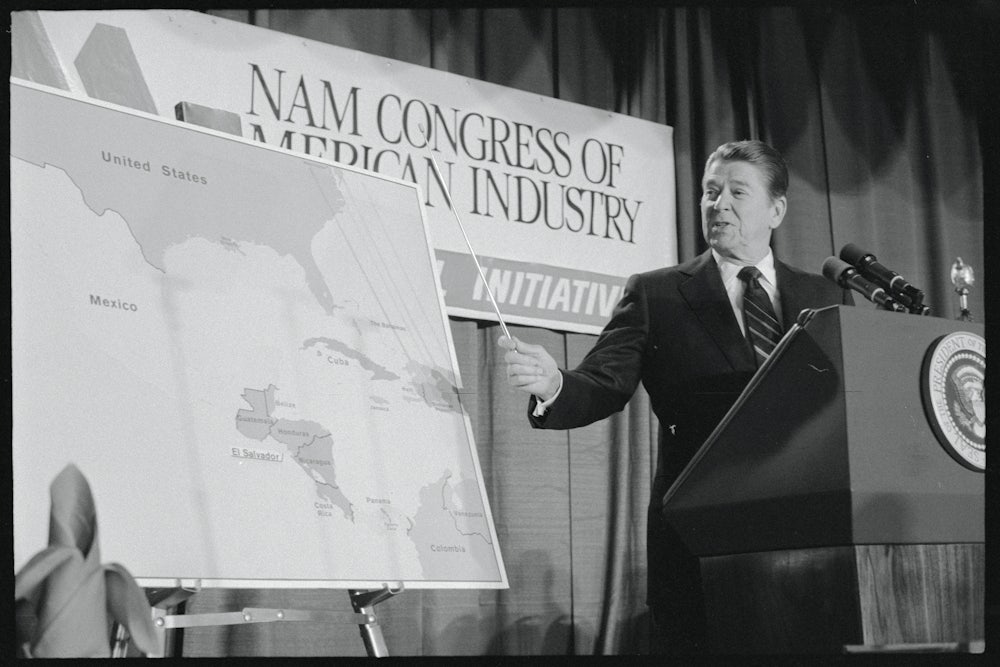

Erik Conway: We started where we did because the National Association of Manufacturers was such a big player for us. Initially, NAM comes into existence in the late nineteenth century to promote tariffs, which is not exactly the anti-government NAM we’ve come to know. But then they very quickly went into opposition to child labor law, and that’s where we pick up the story because that’s where we find the beginning of this ideology of business freedom and their efforts to convert that into an understanding of American freedom overall.

N.O.: And NAM invents this ideology out of whole cloth. It’s a pure invention. You don’t find “free enterprise” in The Constitution, you don’t find it in the Declaration of Independence, or the Bill of Rights, and you don’t even really find much discussion of it in any of The Federalist Papers. So it’s a fabrication, but it’s a fabrication that builds on our commitment to the idea of freedom. They take the term “private enterprise,” which is what people used to talk about, and they change it to “free enterprise,” and then they try to construct a story that without “free enterprise,” the whole edifice of American democracy crumbles. They make it a defense of American democracy, even though what they’re arguing for is actually profoundly anti-democratic.

J.M.: Your 2010 book, Merchants of Doubt, examined how corporate-backed scientists obscured the truth about climate change, tobacco, acid rain, and other major issues. How has writing The Big Myth helped you better understand the phenomena you investigated over a decade ago?

N.O.: I don’t think it changed the way I viewed the key players in the story of Merchants of Doubt. What it changed was my understanding of just how deep the story was. There was a point in writing this book when we thought the story would start with Ronald Reagan. And then we quickly realized that it was much older, especially because NAM was this key player. NAM is actually still fighting climate action today: I just recently learned that they’ve been fighting disclosure rules about conflict minerals. NAM was this obviously key figure that quickly took us back into the 1930s. In Merchants of Doubt, we thought that the tobacco industry had really invented these strategies of disinformation, of experts for hire, all that stuff. But it goes back much, much further.

J.M.: A metaphor that constantly appears in American discourse is that of the “marketplace of ideas.” What does your book have to say about how we should understand this metaphor?

N.O.: One of the things that comes out in our story is just the unbelievable hypocrisy and venality of some of these people who are publicly defending competition, saying that competition lets the best man win, that it brings out the best, is meritocratic, etc., but in reality, are working behind the scenes to manipulate so many things in ways that deny competition.

When they decide to promote free-market neoliberal ideology at the University of Chicago, they don’t put out an advertisement or call for proposals. They handpick individuals who they believe who they know will help them give credibility to their arguments about capitalism and freedom. And then they systematically fund them, including Milton Friedman, who becomes one of the most famous economists of the 20th century. It’s not a competitive process. Friedman does not rise to the top because he competes in the marketplace of ideas.

E.C.: The marketplace of ideas is rigged just as casinos are rigged in favor of the house.

N.O.: But at least when you go to a casino, you know that it’s rigged. But you don’t know, when you read Ayn Rand’s novels, for example, that she’s also writing censorship codes.

J.M.: You argue that we should not be concerned with “capitalism per se,” but rather with “how we think about capitalism, and how it operates.” What would a well-regulated capitalism look like to you?

E.C.: One of the ways we initially thought about framing this work is around the idea that there are many varieties of capitalism. The particular problem in the United States is the kind of extremist, anti-regulatory policies of the business world. We used to have a much larger union penetration, and therefore the wage inequality we see now was far less bad. We see it throughout most of the European countries: They still have elements of the system that are capitalist, but they are not the extreme forms that we have. But we’ve bought into this binary that it’s either unregulated free-market capitalism or communism. And that’s just not the truth of the matter.

J.M.: Do you see any signs that the fever of market fundamentalist ideology is beginning to break?

E.C.: I think so, because as far as I can tell, the leadership of both parties no longer buys this mythology of unregulated capitalism. The Trump Administration imposed tariffs on Chinese goods and on other countries as well, and the Biden administration kept them. Republicans are trying to regulate tech companies, because they think they’re being unfairly censored, even though, as far as I can tell, censorship is a red herring. But they seem to be serious about it. And there’s the Biden administration’s climate plan: instead of going with market-based solutions, they’re subsidizing desired industries and making sure that those chosen industries are national industries. They have this idea of reshoring a new green production economy. None of those are free-market ideas. So something’s changing. What it will become in the future is the part I can’t see, but I think it’s true that the market fundamentalism fever is breaking.

N.O.: Yes, although with that said, you can still find it on the pages of The Wall Street Journal. One of the things that’s tricky is that the Republican Party is kind of in a bind now, because so many of the things they’ve argued for clearly have failed. There’s this tension, because on the one hand, as Erik said, there are Republicans who like protective tariffs. And when their own interests are at stake, you certainly see conservatives and Republicans at the federal trough, just like everyone else. But at the same time, they’re still committed to this anti-government ideology. You saw that really clearly in Sarah Huckabee Sanders’s response to the State of the Union, where it was all big, bad federal government.

Among Democrats, Biden is really departing from what has been the mainstream Democratic position under Obama, and before that, Clinton. Clinton really bought into the deregulatory ideology, with in some cases pretty severely bad consequences. I think a lot of people have seen the ways in which the ideology of market fundamentalism has failed us. Climate change is the obvious issue, but there’s also the opioid crisis, the lack of affordable housing in major American cities, income inequality, and so many other examples of where these policies haven’t worked.