In her 1986 profile of Artforum editor Ingrid Sischy, Janet Malcolm describes critic Rosalind Krauss’s Greene Street apartment as “one of the most beautiful living places in New York.” Its beauty, she writes, “has a dark, forceful, willful character. Each piece of furniture and every object of use or decoration has evidently had to pass a severe test before being admitted into this disdainfully interesting room…. No one can leave this loft without feeling a little rebuked: one’s own house suddenly seems cluttered, inchoate, banal.”

For the writer of nonfiction, reading Janet Malcolm has a similar effect. In her books, each room is furnished with extreme care and control. Their occupants—psychoanalysts sparring over Freud’s legacy, biographers at war with the Sylvia Plath estate, artists and poets, lawyers, journalists, and critics—are vividly rendered characters, surrounded by painstakingly chosen objects, set pieces, and ideas, all equal in craft and complexity. Everything is in its proper place; nothing is superfluous. Malcolm’s books are, in other words, disdainfully interesting. Having luxuriated for weeks in Malcolm’s literary abode, returning to the shabby dwelling of my own prose—with its overstuffed couches, cluttered coffee tables, and dog-eared paperbacks—feels a bit like checking out of the Ritz and into a dumpster.

Malcolm was always preoccupied with interiors. Among her first contributions to The New Yorker—where she wrote for nearly six decades until her death, at 86, in June 2021—was a monthly column on design called “About the House.” In works such as The Journalist and the Murderer, In the Freud Archives, and Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession, she uses acutely observed descriptions of living spaces to characterize her subjects. Surfaces, she believed, were richly revealing. Journalists and psychoanalysts, she told Katie Roiphe in a Paris Review interview, are both “connoisseurs of the small, unregarded motions of life.” The styling of a home, which involves a mix of considered and unthinking motions, was indispensable data for her method. “The unconscious is right there on the surface, as in ‘The Purloined Letter,’” Malcolm says.

Malcolm’s ostensibly unobtrusive reporting style—she conducted her interviews in a state of alert passivity, or as Freud recommended, with “evenly hovering attention”—betrayed no signs of the scathing specificity with which she intended to capture her subjects on the page. And it is, perhaps, because of this dissonance that Malcolm’s subjects have so often resented their own portraits in her books, finding, to their dismay, that there is no therapeutic alliance between journalist and subject. Indeed, as Malcolm frequently insisted, quite the opposite is true. The relation is one of treachery and theft.

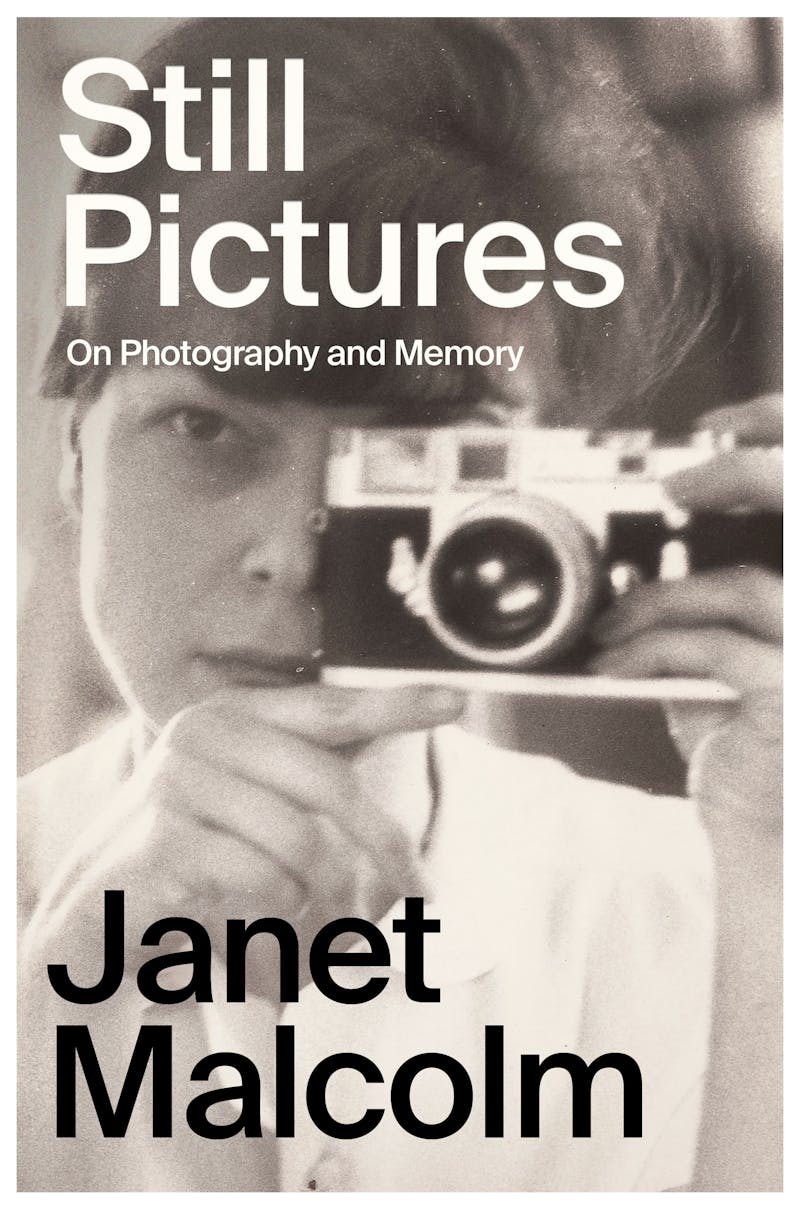

For a writer so relentlessly suspicious of the accounts we give of ourselves, and so attuned to the meager defenses we muster against self-exposure, memoir is a risky medium. In Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory, a newly released posthumous memoir, Malcolm uses a collection of family photos as prompts for free association, attempting to stir her own unconscious against their surfaces. Yet she knows better than to expose herself the way her subjects do; there is no moment when her reticence falters, or she reveals more than she intends, uncovering some hidden, seamy motive behind her own self-talk. Like Freud, who invented psychoanalysis but never lay on the couch, she is unwilling to be subject to her own method. When Malcolm writes in The Journalist and the Murderer that journalism—her vocation—is “morally indefensible,” she means it. She makes no apologies for her hypocrisy.

Instead, this slight and sparing memoir is a testament to those attributes Malcolm most admired (and relied on her journalistic subjects to lack): dignity, discretion, craft, and control. In its guardedness, its respect for privacy, its disinterest in demythologizing, its tenderness and even credulity, Still Pictures makes explicit a muted moral provocation running through Malcolm’s books: that we are all essentially false Pharisees, serial violators of the Golden Rule, constantly claiming exemptions, forbearance, and reprieves for ourselves (and those whom we love) that we would never permit to others.

Janet Malcolm was born to a middle-class family in Prague in 1934. In her earliest memory, summoned from her Czech childhood, Malcolm participates in a village festival—“Little girls in white dresses are walking in a procession, strewing white rose petals from small baskets”—but to her enduring chagrin, the flowers in her own basket are peonies, not roses. She suspects there is something “primitive, symbolic, essential” about this scene. What torments the child? Feeling left out? Failing to conform? No, she concludes, what pains her is aesthetic certainty, the first stirrings of artistic discernment. Already she knows: Roses are better than peonies.

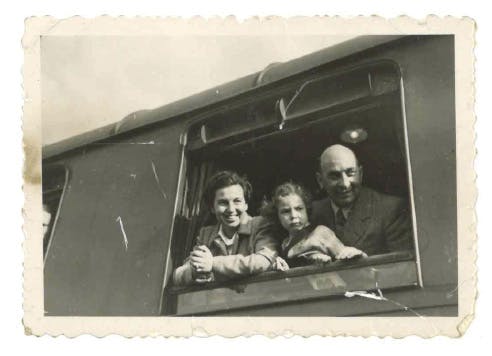

The Czech period is short. The book’s second chapter begins with a black-and-white photo of her parents smiling out the window of a train, their almost–five-year-old daughter seated between them. The expression on the child’s face, Malcolm writes, is most succinctly captured by the Czech word mrzutý—a mixture of “cross, grumpy, surly, sulky, sullen, morose, peevish.” The family escaped Prague in July 1939; her parents “bought an SS man a racehorse” to secure their exit visas (or so the family story goes). The child in the photo with the mrzutý expression is Janet, then called “Jana.” The photographer, who is outside the train watching them go, was a man Malcolm faintly suspected, for many years, of being her mother’s lover.

In the United States, Malcolm’s parents changed their name from Wiener to Winn for “fear of an anti-Semitism that was not limited to Nazi Germany.” Malcolm and her younger sister, Marie, didn’t learn they were Jewish until one of them “brought home an anti-Semitic slur” from school. By then, Malcolm notes, the girls had internalized the (milder but still palpable) Jew-hatred of their adopted home, and she “resented and hid” her Jewishness through adolescence. Malcolm’s parents had concealed their Jewishness out of uncertainty about whether they had actually “found a refuge” in New York. “By the time they understood that they had,” Malcolm writes, “their children’s imaginative life had been deeply affected by their dread.”

Her characteristic restraint, too, took hold early. In her youth, the careful, correct Malcolm tended to befriend headstrong, rule-breaking girls. Her neighbor, Francine, was “a tall girl with attitude … bold and fresh.” Malcolm’s mother disapproved. “Of course, this was what I liked about her: she was the bad girl I was not allowed to be.” “Over the years,” Malcolm writes, “other bad girls entered my life. I was attracted to them for their rebelliousness, and I suppose they were attracted to me the way certain gay men are attracted to straight men in whom they sense—with or utterly without reason—a glimmer of hope of conversion.”

Malcolm’s portraits of her parents are touching, if strangely incomplete, consciously sparing them the betrayals that so often accompany memoir. Her father, a psychiatrist, was “the least pretentious person I have ever known, he never pulled rank on anyone, he had no fear of losing face.” A photograph of him dressed in drag at a Dadaist ball in Prague provides a glimpse of the less austere, more sensuous life he might have lived if not for war, Holocaust, and exile. “My mind is filled with lovely plotless memories of him,” Malcolm writes. “The memories with a plot are, of course, the ones that commit the original sin of autobiography, which gives it its vitality if not its raison d’être.”

Here, Malcolm hesitates. “They are the memories of conflict, resentment, blame, self-justification—and it is wrong, unfair, inexcusable to publish them.” She admits that her father, who was “not concerned with his image,” would likely not have objected to “the recitation of my wounded-child’s grievances.” But her decision is final: “I do not wish to make it. He was a wonderful father.”

Her portrait of her mother, Joan, is messier and therefore more vivid, facilitated by letters as well as photos. “She was warm and loving and unselfish,” Malcolm writes. She was “a good mother.” And like many good mothers, she was also temperamental, prone to moods, volatile—though never in a way that threatened Janet or Marie. In fact, Malcolm is pained by her own seeming indifference to her mother’s needs and desperations. In one letter, Malcolm’s father entreats her to write more often to her mother: “You know that Joan needs more overt display of genuine emotions and more affectionate climate than we all other together,” he writes. And later: “Mother thrives only in this cornucopia of abundant warm emotions and we should give her as much of it as we can.”

Malcolm, away at college and fiercely jealous of her autonomy, was stingy with her letters home. In these conflicts, she variously takes her mother’s side and her own. “I am pained by the ‘Why haven’t you written?’ motif that runs through so many of [my mother’s letters],” Malcolm writes, “I am pained both for her and for myself.” She feels for her younger self, who is “constantly reproached for [her] exercise of the prerogative of youth to be careless and selfish”; and also, for her mother, whose neediness—Malcolm can now see—was only “the sickness of being in love.” Perhaps, she reasons, if young Janet had been able to see her mother as a “fellow-sufferer” (Malcolm, too, was constantly in love with someone), then she would’ve treated her more as a comrade and less as “an adversary whose thrusts I must parry to protect my wobbly independence.”

These family portraits are punctuated by two lovely, parallel aphorisms of Malcolm’s creation—both playing off Tolstoy. The first: “All happy families are alike in the illusion of superiority their children touchingly harbor.” And the second, which comes later in the book: “Yes, all happy families are alike in the pain their members helplessly inflict upon one another, as if under orders from a perverse higher authority.” These lines, and the great troubled tapestry of familial life they weave between them, recall the very best of Malcolm’s work: the high artistry she was capable of, while never quite claiming its mantle; her ability to identify universal truths, even when dealing with the smallest, most particular elements of a life.

And yet, it can’t be denied that Still Pictures is a very different sort of book than Malcolm’s usual fare. Its interior is not at all like the elaborately adorned parlors through which Malcolm usually shepherds the reader. Rather, this room is small and spare, as if rented for the purpose. There is no menace in it, and very little intrigue. An elegant woman sits in a straight-backed chair with a box of photographs in her lap; she thumbs through them while telling a slow, quietly moving story. Every so often we see her eyes go distant, then narrow and glint; something delicious has occurred to her, something devastating. We lean closer, feeling a charge in the air. But she does not betray herself.

Reading Still Pictures, I felt myself wishing for Malcolm to go deeper, to twist the knife. What would a memoir written in the Malcolm-style be like?

One of the signal pleasures of her books is their intrusiveness—her habit of taking in the almost endless particulars of a scene, and culling a ruthless insight from them. There is a moment, for instance, near the end of The Silent Woman—Malcolm’s brilliant reflection on Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, and the sordid enterprise of biography—where Malcolm has gone to visit a man named Trevor Thomas, the last person to see Plath before her suicide. She is startled to find his home “a depository of bizarre clutter and disorder.” She writes,

along the walls and on the floor and on every surface hundreds, perhaps thousands, of objects were piled, as if the place were a secondhand shop into which the contents of ten other secondhand shops had been hurriedly crammed, and over everything there was a film of dust: not ordinary transient dust but dust that itself was overlaid with dust—dust that through the years had acquired almost a kind of objecthood, a sort of immanence.

Surrounded by a lifetime of objects accumulating immanent dust, Malcolm imagines Thomas’s house as “a kind of monstrous allegory of truth.” And it rebukes her in a different, perhaps opposite, way than did Rosalind Krauss’s gorgeous, if overly considered loft. Compared to the “mess of Trevor Thomas’s house, the orderly houses that most of us live in seem meagre and lifeless—as, in the same way, the narratives called biographies pale and shrink in the face of the disorderly actuality that is a life.”

Interiors, again, are her favored metaphor for the relation between art and life, for the writing process, and her qualms about it. It is the task of the writer to clean house, to throw certain things out and decide what to keep. “The goal is to make a space where a few ideas and images and feelings may be so arranged that a reader will want to linger awhile among them, rather than to flee, as I had wanted to flee from Thomas’s house.” To make, in other words, a livable accommodation. This task, Malcolm notes, is not only arduous but treacherous. Necessarily, it involves concealment and elision, the danger of failing to capture the truth in its “magisterial” messiness. What if one throws out the wrong things? Or what if one can’t stop, and the house is left bare?

What she doesn’t say, but is everywhere implied, is that the task “of housecleaning (of narrating)” leaves as many marks of the writer’s own personality—conscious or unconscious—as do the choices we make about decorating our own homes. This, of course, restates Malcolm’s enduring insight: that journalism (like biography) is a kind of theft. Journalists and biographers are burglars who break in, rifle your drawers, then stay and redecorate. If you’re unlucky enough to be their subject, i.e., the homeowner, your preferences will soon cease to matter; once moved in, the burglar feels obligated only to himself, to his own narrative aims, and, somewhat bewilderingly, to a stranger, a visitor neither of you has met, who is due to arrive shortly, and whom, for some reason, the burglar is desperate to entertain and make comfortable.

Writers, Malcolm insists, are obliged to be hospitable, if only to their readers. When she writes that Gertrude Stein—an author of notoriously forbidding, solipsistic prose—treats her reader as “an uninvited guest arriving on the wrong night at a dark house,” we know just what she means.

Malcolm, by contrasts, is a nimble and considerate host. Her books whisk us through rooms of chattering guests, all of whom reveal more than they intend. As we approach an elderly couple, she points to the man, a moth-eaten psychoanalyst inhaling canapés, and, in a conspiratorial whisper, renders a concise and bracing judgment of his character. As she writes of one of the Freudians she interviews in Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession, “He was a man without charm, without ease, without conceit or vanity, and with a kind of excruciating, prodding, twitching honesty that was like an intractable skin condition.” Her description reaches its denouement at the exact moment we arrive at the couple’s side, so that her withering verdict is just dancing on the threshold of our consciousness when her voice rises, reacquiring its benevolence, to introduce the good doctor so-and-so and his wife. When the man speaks—for several paragraphs—the accuracy of her assessment is clear.

But wait, is there not more to this dinner party? Something sinister? The guests begin to look around at one another suspiciously, whispering in little clutches. Why exactly have they been gathered here anyway?

Roiphe notes the “atmosphere of sleuthing” that pervades Malcolm’s books; no matter how dry or academic their subject matter, “a palpable sense of the forbidden propels her narrative forward.” In the Paris Review interview, Malcolm disavows any “conscious” influence from the mystery writers she enjoys—Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, Agatha Christie—but the quality of detective fiction is unmistakable in her work. A plot is afoot. A crime has been committed; a burglary, a con, a murder. Someone is going to be accused. (The biographer, with the unpublished letters, in the footnote …) Malcolm’s insistence that the work of writing is pervaded by seduction, betrayal, and violence no doubt flatters the writer’s sense of their own power. But the truth, that writers relish what Malcolm calls “the freedom to be cruel,” is at least faintly intelligible to anyone who has been written about.

What antagonized readers tend to miss—those doyens of journalism who reacted with such rancor to the opening lines of The Journalist and the Murderer—is that Malcolm never exempts herself from suspicion. In these scenes, Malcolm is always both the all-seeing Poirot, and his lead suspect. (The journalist, with the tape recorder, at Chez Panisse …) When Malcolm writes that journalism is “morally indefensible,” that “malice remains its animating impulse,” that biography depends on “society’s fundamental and incorrigible nosiness,” she is indicting herself. And, as she tells us, again and again, she pleads guilty to the charges. “Being aware of your rascality,” she says, “doesn’t excuse it.”

The more interesting question, to me, is what to make of her apparent acceptance of this hypocrisy or, perhaps better stated, her willingness to endure its ambivalence. For if Malcolm often assigns herself the role of perpetrator, she frequently expresses terror at, and takes extensive measures to avoid, being the victim. “The act of snooping carries with it a certain discomfort and unease,” she writes, understatedly, in The Silent Woman; “one would not like to have this happen to oneself.” When she is interviewed by Roiphe, she refuses to sit for the sort of meandering, long-form interrogation—punctuated by the ominous click-on and click-off the tape—that she prefers for her own work. “She has agreed to do the interview but only by e-mail,” Roiphe writes. “In this way she has politely refused the role of subject and reverted to the more comfortable role of writer.” Roiphe has even consented to allow Malcolm to tinker “gently” with her questions. In other words, Malcolm regularly subjects others to treatment she would never abide.

So averse is she to self-exposure that Malcolm almost didn’t write Still Pictures. In a 2010 essay entitled “Thoughts on Autobiography From an Abandoned Autobiography,” Malcolm explains that she found the journalistic habits of “aggression” and “heartlessness” ill-suited to the genre. “Autobiography is an exercise in self-forgiveness,” she writes. If the freedom to be cruel, as Malcolm says, is “one of journalism’s uncontested privileges,” then perhaps the freedom to be kind is the privilege of memoir. “The older narrator looks back at his younger self with tenderness and pity, empathizing with its sorrows and allowing for its sins.” One tells the story not as a journalist would, “but as a mother might.”

There is a moment that shows Malcolm’s hypocrisy in a different light, however. It comes from Sylvia Plath’s diaries. As Malcolm recounts in The Silent Woman, Hughes and Plath “have gone to walk at the end of a wet, misty day.” Plath has brought a pair of silver-plated scissors, intending to snip a rosebud from the park’s garden, to replace the one blooming in her living room. As she is doing so, several “hulking” (Plath’s word) girls emerge from a rhododendron grove. They’ve been stealing bushels of flowers. Plath goes into a rage. As she records in her diary, “I felt bloodlust … wanting strangely to claw off her raincoat, smack her face, read the emblem of her school on her jersey and send her to jail.”

Malcolm writes, “It isn’t lost on Plath that she is the pot calling the kettle black. ‘I wondered at my split morality,’ she writes. ‘Here I had an orange and a pink rosebud in my pocket … and I felt like killing a girl stealing armfuls of rhododendrons for a dance.’” Furtively Plath seeks to absolve herself, distinguishing their relative crimes: She took just one rose a week (“aesthetic joy for me and Ted, and sorrow or loss for no one”); these girls were “ripping up whole bushes.” But her hatred is wildly disproportionate to the crime: She feels “a blood-longing” to rush at the girl “and tear her to bloody beating bits.”

The scene bears a striking resemblance to the type of encounter Malcolm stages in her work. In books like The Silent Woman, The Journalist and the Murderer, and In the Freud Archives, it is Malcolm who confidently strides up to her hulking journalists, biographers, and analysts, reproaches them for thoughtlessly snatching up flower beds in the dark—for manipulating their subjects and betraying their confidences; for snooping around where they shouldn’t and taking what isn’t theirs—all while a scissor glints in her own pocket. (The writer, in the garden, with the silver-plated scissors.) For Plath and Malcolm, the question of who has the right to wield the scissors is irresolvable; it resists adjudication. The language of ethics is always uneasily translated into the language of art (as Malcolm discovered whenever she found herself reporting from a courtroom).

In the encounter with the bad girls in the garden, Malcolm concludes, Plath “was, of course, encountering the ‘not-nice’ part of herself, the ‘true self,’ … that was not afraid to rip up whole bushes, because this is what it is the business of the artist to do. Art is theft, art is armed robbery, art is not pleasing your mother.” The trouble with the girls in the garden is not that they are engaged in a selfish or criminal act; it’s that they are not artists. They will not know what to do with the beauty they have unearthed. Plath resents and envies their clumsy courage; when she musters it herself, she will come into her genius. (Not to mention, roses are better than rhododendrons, too.)

Those of us who do not resent Malcolm her hypocrisies, the licenses she grants herself but denies to others, are probably those who see, in her best work, something more and other than mere journalism. There is a difference, after all—at times, a contradiction—between journalistic integrity and artistic integrity. Artists take more than their share. They are selfish, mercenary, self-focused. Usually, they have to be. It feels incredibly silly to talk this way; probably Malcolm would cringe at the conflation. But I have never once resented her for pulling up the rosebush by the roots. If I have any wish, it is that she had done so more often—and with even more greedy abandon.