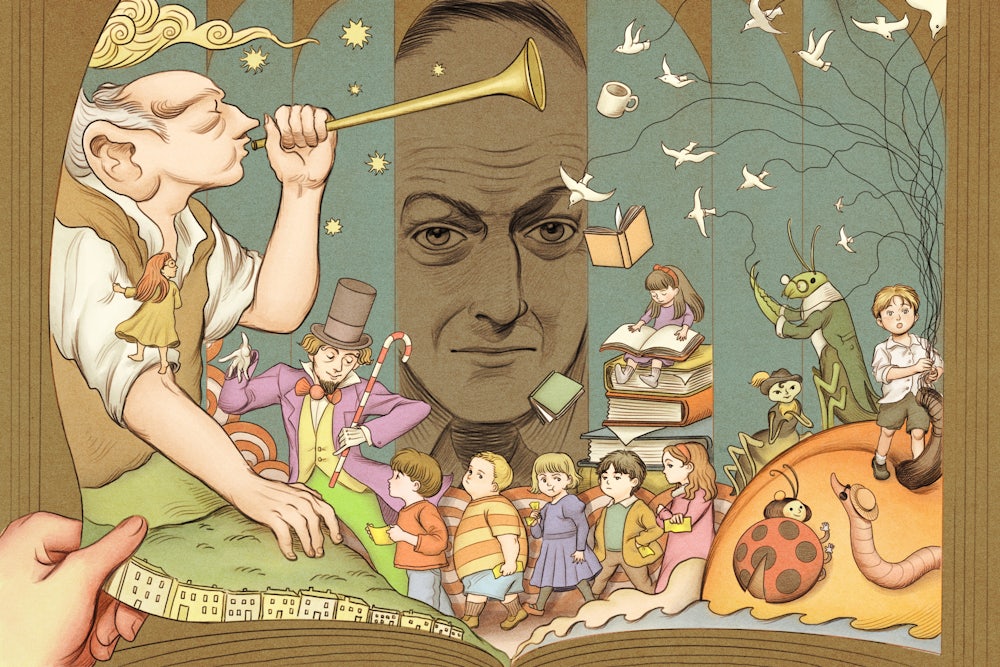

Roald Dahl’s children’s books are not exactly the nicest. Dahl’s characters glory in insults and meanness. The adults are generally horrible, the children gleefully vengeful; his bullies usually get their comeuppance. So when it came out recently that Dahl’s publishers had edited new editions of his work with the help of “sensitivity” readers, it was hardly surprising—and it was also hard not to laugh. How much can a handful of essentially cosmetic changes really do? On episode 63 of The Politics of Everything, hosts Laura Marsh and Alex Pareene talk with literary critics Merve Emre and Christian Lorentzen about the unpleasantness in Dahl’s work, the interest his publishers may have in making the books more palatable, and how such edits fit into a long tradition of bowdlerizing fiction, especially that aimed at children.

Alex Pareene: “You are far too respectable,” Mr. Fox tells Badger as they tunnel into Farmer Bean’s secret cider cellar. “There’s nothing wrong with being respectable,” Badger tells his friend, the fantastic Mr. Fox, in Roald Dahl’s classic of children’s literature.

Laura Marsh: Dahl himself had a lot of fun with Mr. Fox, the unrespectable and unrepentant thief. But in a newly revised edition of the book, Mr. Fox is indeed quite a bit more respectable. He now has daughters instead of sons. One of those daughters sneaks a sniff of Bean’s hard cider instead of a swig. At the end of the story, rather than promising his friends and family that they shall all eat like kings from now on, he substitutes a less gendered promise: “They shall all eat like royalty.”

Alex: These are just a few of the changes—and some of the least controversial ones— made to Dahl’s books by his estate and his publisher Puffin UK, with assistance from Inclusive Minds, a sensitivity reading collective. Dahl’s villains are no longer called “fat” or “crazy.” Matilda now reads Jane Austen instead of Rudyard Kipling.

Laura: In response to an outcry both in the U.K. and the U.S. over these alterations, Puffin announced that prior versions of Dahl’s books would remain on sale alongside these new, more sensitive additions. But what led them to make the changes in the first place? And why exactly did the prospect of updating these unrepentantly nasty books cause such an uproar to begin? I’m Laura Marsh.

Alex: I’m Alex Pareene.

Laura: This is The Politics of Everything.

Laura: For Roald Dahl, writing for children didn’t mean writing particularly wholesome stories. His books are full of jagged edges. They revel in gruesome details, tales of spite and revenge, of cruel parents, sadistic teachers, witches and twits. Miss Trunchbull, the headmistress in Matilda sees her students as a bunch of “nauseating little warts,” “ignorant little slugs,” “empty-headed hamsters,” and “stupid globs of glue.” Inventive insults are a signature of the books, along with the scratchy illustrations by Quentin Blake. Merve Emre, a critic and professor of literature, recently wrote an essay about Roald Dahl for The New York Review of Books. “His fictions,” she writes, “are some of the stupidest and crudest I’ve encountered.” She digs deep into the nastiness of Dahl’s books, and what to make of it. Merve, thanks for joining us.

Merve Emre: Thanks for having me, Laura and Alex.

Laura: So you spent a lot of time reading, I presume, rereading Roald Dahl at this point. You read his books as a child yourself. You read them to your children and you read them for the piece that you wrote. What’s it like to be inside his world?

Merve: Well, I read them when I was writing the piece to my own children, who were four and six at the time. What struck me about their reactions to him, which invariably colored my reactions to him, was how bored they were. This was not what I had expected. My own memories of reading Dahl were of being riveted by some of the very things that you mentioned in your introduction, Laura, but particularly riveted by the authorization or the permission to revel in cruelty, in insults, in meanness, and in insults and meanness and physical violence as being away for those who had been oppressed in his books, those who had been small or powerless or weak to get their due. So when I read it to my children and found that they were bored and that I was bored, I thought perhaps there’s something there that really isn’t all that interesting.

Laura: I remember reading a book like The Twits, or actually having it read to me. I don’t think I would’ve continued with it if it hadn’t been read to me and I was just thinking, “This is so stupid, I hate this, this whole thing of plates of worms.” I was not that old at the time, but I just felt I was better than that. It’s not the humor I’m into, it’s just not how I’m wired. But a lot of kids love that and they’re waiting for the next gross detail, and I enjoyed a lot of his other books. Can you talk us through some of the range of nastiness, the world of nastiness, of Roald Dahl? And we’re not using nasty as a pejorative here, even though we will arrive at some critical judgments by the end of the episode.

Merve: So when we talk about the nastiness of Roald Dahl, and yes, that nastiness comes in many flavors, I sometimes wonder whose sense of nastiness those books are appealing to. Is it really the children who are drawn in by stories of people hurting one another or hurting animals? Stories of people being shrunken down to size or stretched out really tall and long, stories of children who behave badly, being punished in all kinds of disproportionate ways, and children who behave well, punishing those who want to punish them in all kinds of disproportionate ways? Is that nastiness really appealing to children or is it appealing to the adults that are reading those books to their children?

Laura: That’s interesting, because I’ve always thought about them from the child’s perspective. Take a story like Matilda—you have a horrible parent, the really horrible school teachers, and then one nice one. Ultimately it’s Matilda who gets her revenge. It’s this tale of the underdog triumphing. But what you are saying is if you are the adult reading the book to children, then you maybe secretly identify with Miss Trunchbull and you would never admit it to yourself. But maybe that’s part of the fun: “Maybe I could be this horrible, maybe I could be this mean to these awful kids that I have to spend all day teaching.”

Merve: Well, I’m a professor of literature, Laura, so I feel like anything I say on that front might incriminate me, but that that’s certainly one way to read it. The other thing I would say is that I think a lot of adults often feel quite small and quite trampled on, and it wouldn’t surprise me if they were also identifying with the powerless children in the books, the children who hold out the possibility to them that if only they knew how to get big and bigger than the bullies in their midst then they could somehow have control over their own destinies in ways that they don’t anymore.

Laura: To be successful as a kid’s book, you do have to appeal to parents and children.

Merve: I think that’s absolutely right. I was thinking too that one of the things that’s interesting to me about Dahl and his particular place in the field of children’s literature is that he is probably the only author we can think of who did the vast majority of his work in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, and is still being read today. I think this actually gives him a really unique status in the field of children’s literature, which is, I would argue, the most presentist of all of the different genres of fiction or of prose that we might encounter.

Alex: I relate that to what you were saying about the appeal of these books. I haven’t actually gotten to Dahl with my own kid, who is six, although I did, I think, inspired by this episode, go out and purchase James and the Giant Peach this weekend. So we’ll see how that goes over. I remember reading his books myself as a child, the sort of child who would sort of pick up anything and read it. I could not relate to the gothic English unpleasantness of all of the adults because the adults in my life, the teachers in my life, didn’t act that way. So it’s not that it was the wish fulfillment of the child who wishes to be larger, but honestly more the pure escapism of this bizarre world where people were just so much crueler to each other for no reason.

Laura: That’s exactly what it’s like in England. I can vouch.

Alex: Yes, I’m sure, Laura! For you it was all a documentary, but for me it was escapism.

Merve: There is something interesting there. If you read his autobiographies, if you read Boy, you will see how much that kind of cruelty was bound up with his own parents or his own family’s aspirational class status. They wanted nothing more for him to be a public school boy, and I’m using that term in the English sense of it, and when he went to the kinds of schools that he went to, the primary mode of being with other boys that he describes is being beaten and very likely, according to at least one of his biographers, being sexually abused. If anything, what you see in the children’s fiction is the mutation or the concealment of some of that cruelty into forms that seem more fantastic, more gothic, than what he actually lived.

Laura: He came from a generation of writers, from Roald Dahl to John le Carré, and I think even Ian McEwan has written about this, who all had this experience at English boarding schools of being beaten by their teachers and also by the older boys in a system that was condoned and in fact encouraged. There is a sense in which these books are the adult processing that trauma over and over again.

Merve: I think that there are two currents that are running together here: One might be processing that trauma and the other is the fictional reproduction of the violence that led to it.

Laura: You also read the fiction that he wrote for adults. You write about that in your piece, and that’s a lot more overt. How does that change or color your reading of him?

Merve: The short story that I wrote about in The New York Review of Books piece is called “Bitch,” and I don’t need to get into the plot summary too much, but it ends with a man accidentally smelling a sexual stimulant and in his fantasy world growing into a seven-foot penis, a seven-foot purple penis. The way that Dahl describes that growth is something like “bigger and bigger grew my astonishing member.” And we find that same line reproduced a year or two later in James and the Giant Peach, which you’re about to read to your son, Alex: “bigger, bigger and bigger grew my astonishing peach.”

Laura: Nothing sexual about a peach, of course, we all know from the centuries of literature. It’s completely nonsexual.

Alex: No. Sometimes a peach is just a peach.

Merve: Dare I eat my astonishing peach? Yeah … I think it’s not just that the line was cribbed or reworked or whatever, it was that the same imagination of scale and what it might afford us—the power over other people that it might afford us—is operative, I think, in both the adult fiction and in the children’s fiction.

Laura: One of the reasons we are digging into all of this is because of the recent news that Dahl’s estate was working on these altered versions with a company called Inclusive Minds, which went through all of the books and suggested a bunch of changes. The changes are fairly superficial things. They’re changing words like “fat” to “enormous.” They don’t hugely change the meaning. They’re just swapping one word out for another.

Merve: “Hag” to “crone,” “crone” to “hag.”

Laura: Right, and at a certain point you sort of wonder, “Is it possible to actually make Roald Dahl 10 percent nicer by changing a few words?”

Merve: No. It’s a funny exercise and I should say I haven’t been able to find it in me to feel ardently about this on either side, for particularly the reason that you lay out, Laura, which is that none of these changes really make any difference whatsoever to the overall imagination of nastiness or cruelty or the way that power works between children or between adults and children, I do read them as essentially cosmetic, but I would also just go back to some of the things I was saying earlier, which are one, children’s literature is, out of all of the genres we can think of, most sensitive to present political thematics. I don’t know if you’ve browsed the children’s section of a bookstore recently, but you can see this in all of the books that are laid out for your consumption now that the vast majority of them have some social justice or equality, diversity messaging. When I think of some of the other older authors that I’ve read to my children, they include Edward Eager, who wrote the fantastic book Half Magic; they include Enid Blyton, C.S Lewis…

Laura: Also a famously lovely person, Enid Blyton.

Merve: But ultimately it’s not that those people wrote books that were any more or less problematic than Dahl, it’s just that they’re not being read at the same frequency as Dahl is being read, which is why he or his estate feels that they need to be accountable or responsive to the structure of children’s literature now. And maybe the last thing I’ll say is when I went through the list of all of the changes that had been made, it was interesting to see the changes that people had been screenshotting and sharing on social media. But there were also changes that were obviously changes, either changing British English into American English. I don’t know if you noticed those, Laura…

Laura: I noticed the translation of “fanny” to “bum” or something and was like, “That’s not what that means.”

Alex: Yeah, they got rid of a couple uses of “queer” just meaning strange.

Merve: Or just other ways in which the language was either updated or nationalized or globalized, converted into this global American idiom. So I think that all of these kinds of changes are essentially changes that attempt to bring history into the present in one way or another.

Laura: But I wonder how much that makes sense in that I do think children can tell when a book reflects a society that isn’t the one they live in. I remember reading kids’ books from the ’50s when I was growing up in the ’90s, and the children talking in weird ways and calling their moms mother. And I knew that that was an outdated, antiquated earlier period. It isn’t that hard to grasp.

Merve: No, I agree. I actually think this is just more evidence for the point that these changes aren’t really being made for kids.

Alex: Exactly. I do wonder to what extent is people coming across these books and being caught off guard by what is actually contained in them compared to how he has been marketed and sold, especially since his death, where he’s almost this English Dr. Seuss–like figure, to speak of another misanthrope who didn’t actually like kids that much. There’s all of this, like, “the wondrous, fabulous world of Roald Dahl where anything could happen And then his books are this list of often quite funny juvenile insults and horrid language thrown at all sorts of people.

Merve: The other thing to just consider is that on many dimensions, children’s book authors are thinking about and are asking children themselves to think about things like suffering, compassion, inequality, collectivity. One argument we might make is that the estate knows it can’t keep up with those ideas in any substantive way, and so the best it can do is make this series of cosmetic changes. I suppose my overall take on the whole thing is that it shows us a very interesting set of dynamics around the historical construction of children’s fiction at this moment in time and how it might be different from what children’s fiction was and what kinds of fantasies it offered both adults and children 50 years earlier. But this is just me saying, I can’t get worked up in one direction or another about it.

Laura: Thank you so much.

Merve: Of course. That was really fun, guys.

Alex: Read Merve’s essay about Roald Dahl, “Making It Big,” in The New York Review of Books.

Laura: We’ve talked about how readers respond to the nastiness in Roald Dahl, but there are other groups involved in the changes to his work, including the Roald Dahl Story Company, which is currently owned by Netflix.

Alex: After the break, we’ll talk about who stands to gain from a sanitized version of Roald Dahl.

Alex: The plan by Puffin UK to edit some of Roald Dahl’s most famous works kicked up such a stir that the publisher walked back its promise to cease publishing the original versions of the books in question and simply published two versions going forward, giving readers the opportunity to choose their own Roald Dahl adventure. The critic Christian Lorentzen has written extensively on the publishing industry. He wrote recently about the Dahl controversy on his Substack newsletter. The point isn’t to protect children from words like “fat” or “female” or “ugly,” Christian says. The point is not even to atone for Dahl’s notorious antisemitism. “The point,” according to Christian, “is to make money.” Christian, welcome to the show.

Christian Lorentzen: Hey, good to see you guys. Thanks for having me.

Alex: Children’s literature is a major money maker, especially if it’s Roald Dahl, who has been in print for many, many years and already had various movies made out of your work. Netflix purchased streaming rights to Dahl’s entire catalog for $686 million in 2021. To what extent, Christian, do you think that, for example, the demands of streaming content to make broadly accessible material for general audiences drove the publisher’s decision to whitewash some of Dahl’s work?

Christian: I would say that it would have to be 100 percent, most likely!

Alex: Got it.

Laura: So maybe we should zoom back to begin with. Why did you decide to write about this controversy? What drew you in?

Christian: The morning that the Telegraph story by my friend Ed Cumming and a couple of his colleagues broke, people were losing their minds on Twitter about it. I was talking on the phone to one of my writer buddies and I proffered a much more cynical view to him: that the corporate owners of the estate are now free to do anything they want with the books and nothing will stop them from doing so. I recalled my own experience bowdlerizing Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet. I had worked at SparkNotes, which then was owned by Barnes & Noble, for one year as an editor and production manager. In the course of leaving that job, I assigned myself a lot of freelance work. I rewrote Macbeth and Romeo and Juliet for 800 bucks a pop. I noticed a few days ago that Romeo and Juliet (No Fear Shakespeare) is currently the second best-selling theater book on Amazon, 20 years after I wrote it.

Alex: This is probably by far the most widely read thing you’ve done, right?

Laura: I didn’t know it, but that’s probably the first of your works that I’ve ever read. I’m sure I read those in high school. It’s a funny conceit—you’re saying, “OK, I rewrote Shakespeare, so why shouldn’t someone else rewrite this?”

Alex: “No one could stop me, the bard himself could not stop me from rewriting it.”

Christian: You’re rewriting Shakespeare to take it out of verse and put it into prose— make it easier to read, simplify the vocabulary for children who are encountering Shakespeare for the first time. And it should be said that in those volumes, the original is on the left hand side, and I’m on the right hand side. So it’s not just me.

Laura: Right, with those books, the idea is that you will progress from Christian Lorentzen’s Shakespeare to Shakespeare’s Shakespeare, and that this will be a sort of feeder; you’ll be able to understand what’s going on and then you’ll be able to go and read real Shakespeare. But with these new additions of Roald Dahl, originally, at least, the idea was that the new clean versions would replace the old unfortunate ones.

Christian: I guess what I’m saying is that bowdlerization of any writer after their death is possibly inevitable. They’re more likely to be bowdlerized at some point than they are to survive.

Laura: Or being bowdlerized is a symbol that you’ve made it. Because the fate of most writers is—

Alex: Obscurity.

Christian: Oblivion.

Laura: Most writers won’t be read by the end of their lifetime, let alone after their deaths.

Christian: Or during their life.

Laura: Yeah, you write a great novel when you’re 25, by the time you’re 55, it’s out of print. No one remembers it. So if it survives long enough to be bowdlerized, that means it’s entered some form of canon, even if it’s just children’s book canon. But traditionally, we think of bowdlerization as having a moral component.

Christian: The additions Thomas Bowdler was trying to put together were called The Family Shakespeare. We can imagine what that meant: probably a lot less sex and nasty language about drinking and such.

Laura: One of the criticisms of bowdlerization is that you’re expunging the complexity from the work and that it’s a form of censorship. That has been one criticism of this move with Dahl, right? Suzanne Nossel from PEN and Salman Rushdie have said this is an attack on free speech.

Christian: Certainly in a way it is. However, it’s being conducted by the people to whom the rights have been sold and who own the rights to the intellectual property. The dead no longer control the things they created. Kafka wanted to have all of his writings burned, and Max Brod disobeyed him, which is why we know the writings of Kafka. Yes, what they’re doing is morally censorious, but they’re doing it in the name of preserving a cash cow of intellectual property across as many platforms as possible for as long a time as possible until they no longer own that intellectual property—which, I don’t know, 75 years after Dahl’s death?

Laura: He died in 1990, so the clock has many decades to run.

Alex: So they’re thinking they’ve got to keep these things on the shelves for many years to come in the face of changing taste.

Laura: When this was coming out, I saw people arguing about the fact that the Roald Dahl Story Company was sold to Netflix, and a lot of claims that, well, Netflix of course insisted on this. Then when you look at the timeline, Inclusive Minds was actually brought on before the sale. But I wonder if there’s a sense in which this is doing up a house before you put it on the market. You’re bringing in Inclusive Minds to tidy things up so that you can have a presentable thing to sell to a massive multinational corporation that doesn’t want stray insults and jagged edges in the IP. It wants something really perfect.

Christian: That makes sense to me. They probably got an extra $10 million for those efforts. They got $686 million instead of $676 million.

Alex: I already admitted this, but I went over to the bookstore this weekend and I realized we had no Roald Dahl in the house. I’ve got a six-year-old here, so I picked up James and the Giant Peach, and I asked, “Have you guys seen an uptick in Roald Dahl sales?” And the guy at Greenlight said, “No, but you should check the other store, I don’t know if people read the news in this neighborhood.” But it did make me think, because I was buying it, I had this thought of “Well, I gotta get these versions before they pull ’em. We were joking about whether this entire thing was not just a sort of New Coke stunt. If it weren’t designed—

Christian: —to gin up.... Well, I think that some such things have happened! When the Norman Mailer estate seemed to be planting stories that Mailer was being censored by Random House because Random House declined to pick up a posthumous essay collection, which was just a lot of old stuff repackaged, I took that as a cynical move.

Alex: He needed to get canceled to get some interest.

Christian: Mailer needed to be made dangerous again. Another example that was reported a week after Roald Dahl was that apparently racist language is being taken out of the novels of Ian Fleming.

Alex: There’s another “What do you have left?”

Laura: The thing that is lost in some of these conversations is that it’s OK to read a book and not like it or object to it. You don’t have to remove all the offensive stuff from the book. You can just publish books that have that stuff and people can see them and say, “I take issue with that,” “That’s my opinion,” “I don’t like this book, and that’s part of my taste.”

Christian: I read books that I hate all the time. It does seem sometimes that the culture generally, and I would attribute it to Facebook, really—when Facebook started having people list the books that were important to them as part of their core identities, people began to have a mentality of reading as a form of affiliation, which is understandable if you become a big fan, but there is an idea out there that books have become this “You are what you eat” kind of thing, and I just don’t think that’s true. Because if that were the case, I would have turned into Renata Adler a long time ago.

Alex: It gets, too, at what we’ve been talking about of underestimating children, in the sense that if adults have this attitude that they can be defined by what their tastes are, it definitely is even more true that people think if my children are exposed to this, they will come to embody it. So it’s even more of a moral imperative to clean up stuff for children because if they’re exposed to it, they will certainly begin to adopt it.

Christian: That reminds you of something my mother said when I got my first Rolling Stones record: “You don’t want to be like them!” And I was like, “OK, Mom.”

Alex: She meant, like, you want to quit while you’re ahead though, right? Like don’t just keep touring into your seventies?

Christian: I think she didn’t want me to become a heroin addict and have to get my blood replaced.

Alex: All right, Christian, thank you so much for talking to us.

Christian: Hey, great to talk to you guys. Thanks for having me.

Laura: Thank you so much.

Alex: You can subscribe to Christian’s newsletter, Christian Lorentzen’s Diary, on Substack.

Alex: The Politics of Everything is co-produced by Talkhouse.

Laura: Emily Cooke is our executive producer.

Alex: Lorraine Cademartori assisted on this episode.

Laura: Myron Kaplan is our audio editor.

Alex: If you enjoy The Politics of Everything and you want to support the show, one thing you can do is write a review wherever you get your podcasts. Every review helps.

Laura: Thanks for listening.