In 1960, the sociologist Daniel Bell published a book titled The End of Ideology that argued the ideological battles of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had subsided. A “rough consensus” had emerged, Bell wrote, at least in the West, on the need for a welfare state, a mixed economy, and political pluralism. President John F. Kennedy echoed Bell’s theme in a speech at Yale’s 1962 commencement. “The central domestic issues of our time,” Kennedy said,

relate not to basic clashes of philosophy or ideology but to ways and means of reaching common goals—to research for sophisticated solutions to complex and obstinate issues…. What is at stake in our economic decisions today is not some grand warfare of rival ideologies which will sweep the country with passion, but the practical management of a modern economy.

The moment didn’t last. Ideological warfare resumed in the United States with the rise of the New Left in the late 1960s and with the rise of the New Right in the early 1980s. Today, those ideological storms have subsided. This time, though, ideology is over not because right and left have reached rough consensus; far from it. The contest is done because the Republican Party walked off the field. We have arrived at the end of GOP ideology.

Obviously, we haven’t reached the end of political division; that’s worse today than it’s been since liberals and conservatives duked it out during the ’60s and ’70s over civil rights, the Vietnam War, and Watergate. Indeed, the angry prejudices, paranoia, and folklore ricocheting through social media, talk radio, and Fox News enjoy much greater reach today than they did half a century ago.

To the contemporary ear, the word “ideology” is synonymous with that kind of toxic stew. But when I say that GOP ideology has ended, I’m using the word differently. I’m not using it to describe pathologies, or resentments, or ethnic hatreds. I’m not using it to describe the mob’s surrender to an authoritarian leader. I’m not using it in any of the broadly pejorative senses in which the term is commonly used today.

Rather, I’m using the word “ideology” to describe, in a neutral manner, some set of reasoned and coherent principles and policies, however mistaken, around which a society can be organized. That’s how Bell (mostly) used the term. He called ideology “the commitment to the consequences of ideas.”

The GOP no longer even pretends that its pursuit of power is rooted in any such commitment. The conservative ideas that came to fruition four decades ago during Ronald Reagan’s presidency didn’t stand the test of time, either because they were faulty from the start or because circumstances and public opinion changed, and the few new ideas taken up by some Republicans in recent years inspire too much disagreement, within either the party or the broader electorate, to rise to the level of party doctrine. The Republicans’ failure to produce a party platform in 2020 proved beyond a doubt that there was no such thing as a GOP ideology. There remains none today. Instead, we have what is commonly, and accurately, described by political observers, including many conservatives, as GOP nihilism: a party’s self-perpetuation for its own sake driven by an opportunistic indifference to fact and reason, expressed through coarse and incendiary rhetoric.

When you really pay attention to how today’s Republicans speak, I don’t know how you can call it ideological. During January’s 15-ballot donnybrook over choosing the next House speaker, was it ideological for Representative Kat Cammack, Republican of Florida, to accuse Democrats of bringing “popcorn and blankets and alcohol” to watch her party’s display of disunity? When the Democrats howled in outrage at this strangely arbitrary fabrication, was it ideological for Cammack to add, “As evidenced by my colleagues’ actions”? Give me a break. Witless, juvenile, and pointless, yes. Ideological? Don’t flatter her.

The most nihilistic project of the new majority-GOP House is the establishment of a Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government. This is a brazen play to run interference against the various criminal investigations of former President Donald Trump. The select subcommittee’s chairman, Jim Jordan, is also chairman of the House Judiciary Committee. Jordan’s chairmanship of the select subcommittee is a glaring conflict of interest, given that, along with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, Jordan refused to comply with a subpoena during the last Congress from the committee investigating the January 6 insurrection. Jordan defended Trump during two impeachments, and he told Fox News after the 2020 election, “I don’t know how you can ever convince me that President Trump didn’t actually win this thing.”

The weaponization subcommittee’s foremost target will be the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which during Trump’s presidency became a whipping boy for the right, contradicting the GOP’s claim to champion law and order. In addition to protecting Trump as best it can, the subcommittee will discourage the FBI from (to quote language from a Republican Judiciary Committee staff report issued in November) “artificially inflating statistics about domestic violent extremism in the nation.” An imagined leftist “double standard” in investigating terrorism is one of Jordan’s favorite hobbyhorses, and it’s sheer denialism. No honest expert disputes that violent political extremism in the United States is overwhelmingly domestic in nature, and that the bulk of it comes from the right. That’s been true going all the way back to 1948, according to a 2022 report by criminologist Gary LaFree of the University of Maryland and others. What’s new is the right’s boldness in expressing support for political violence. A November 2021 poll by the nonprofit Public Religion Research Institute found that three times as many Republicans as Democrats agreed with the statement, “Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.” No fewer than 30 percent of Republicans concurred.

These “true American patriots” went kinetic on January 6, 2021. Initially the Republican National Committee voiced outrage. “These violent scenes we have witnessed do not represent acts of patriotism,” an RNC statement said, “but an attack on our country and its founding principles.” Alas, this view was not sustainable, and in February 2022 the RNC excused the riots, incredibly, as a form of “legitimate political discourse.” There is no conservative principle that would permit violence and vandalism to bar Congress from certifying a presidential election.

The Republican Party signaled most definitively that the cupboard was bare when President Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and deputy campaign manager Bill Stepien (who in mid-July 2020 became campaign manager) turned their attention to writing the 2020 Republican platform.

Political reporters tend to downplay the importance of party platforms, and certainly their influence has diminished over time. But platforms remain significant in clarifying what it is that a party stands for, and even what laws may get passed. Lee Payne, a political scientist at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas, examined party platforms from 1980 to 2004 and found that members of Congress voted in accordance with their party platforms 82 percent of the time. For Republicans, it was 89 percent of the time. “So, yes,” Payne told Vox, “I would say it matters.”

Kushner and Stepien wanted a GOP platform that was less lengthy than the 58-page 2016 platform and more appealing to swing voters. In 2016, the Trump campaign had stayed out of the process, giving the Christian right a free hand. (The sole exception was that a campaign aide persuaded the platform committee to soften its language supporting military aid to Ukraine.) As a result, the 2016 platform ended up saying, among other things, that the Supreme Court’s ruling affirming a right to gay marriage “robbed 320 million Americans of their legitimate constitutional authority to define marriage as the union of one man and one woman.” At a December 2019 meeting reported by Jonathan Swan of Axios, Kushner said he wanted to avoid repeating anti-gay rhetoric.

A one-page platform was produced, according to Swan, and Trump was all for it. But the Axios story infuriated party activists, and, rather than ignore them or negotiate changes, Trump and the Republican National Committee dispensed with a party platform altogether, citing, implausibly, logistical difficulties resulting from the Covid outbreak. (The Democrats, during the same pandemic, had no difficulty producing a platform of their own.) To justify its decision, the Republican National Committee adopted a resolution affirming that, if a platform had been written, it “undoubtedly” would have reasserted, unanimously, “the party’s strong support for President Donald Trump.”

“Trump owned the RNC in 2020,” William Palatucci, an RNC committeeman from New Jersey, told me. “They were just following orders.” In effect, the Republican Party pledged to favor whatever it was Donald Trump would want to achieve in his second term. But nobody could identify what that was—least of all Trump himself.

Trump made his lack of an agenda abundantly clear in a series of TV interviews in the summer of 2020. During convention week, Peter Baker of The New York Times asked Trump to lay out a second-term agenda. Here is how Trump answered:

But so I think, I think it would be, I think it would be very, very, I think we’d have a very, very solid, we would continue what we’re doing, we’d solidify what we’ve done, and we have other things on our plate that we want to get done.

By this time, Trump’s campaign, probably in response to negative stories about the GOP’s null-set platform, had released a list of 50 “core priorities” for the second term, including tax cuts, cuts to prescription drug prices, and “teach American exceptionalism.” But Trump wouldn’t parrot even these largely platitudinous policy goals. He either didn’t read them, didn’t remember them, or didn’t find them particularly interesting.

Writing for Politico that summer, Tim Alberta asked Frank Luntz, the pollster who helped Newt Gingrich develop the GOP’s “Contract With America” in 1994, to tell him what the Republican Party stood for. “I can’t do it,” Luntz replied. “For the first time in my life, I don’t know the answer.”

Today, Donald Trump is no longer president, and his prospects for returning to the White House look bleak. Republican officeholders remain wary of crossing Trump, but Trump’s influence over the Republican Party was weakened by the GOP’s disappointingly small gains in the midterm elections. Still, the Republican Party continues to believe, like Trump, in nothing.

That isn’t to say the GOP lacks ideological factions. There are 222 Republicans in the House and 49 in the Senate. Among these are libertarians, moderates (yes, a few remain), foreign policy hawks, noninterventionists, fiscal conservatives, supply-siders, abortion opponents, abortion supporters, pro-business traditionalists, and anti-business populists. There have always been ideological divisions among Republicans.

What’s new is that these factions no longer share anything resembling a set of principles. Increasingly, they don’t bother even to pretend. Meanwhile, Republican ranks have been fattened by self-contradicting opportunists like Representative Matt Gaetz of Florida (who said McCarthy “sold shares of himself” in the form of the concessions he made to win the speakership, then later called these same concessions “a big win for the House of Representatives”) and Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia (who called President Joe Biden “a piece of shit” for pulling troops out of Afghanistan, then later denigrated military service by saying it was “throwing your life away”). The only thing that unites these cynics with the GOP’s other antagonistic factions is their professed loathing of Democrats.

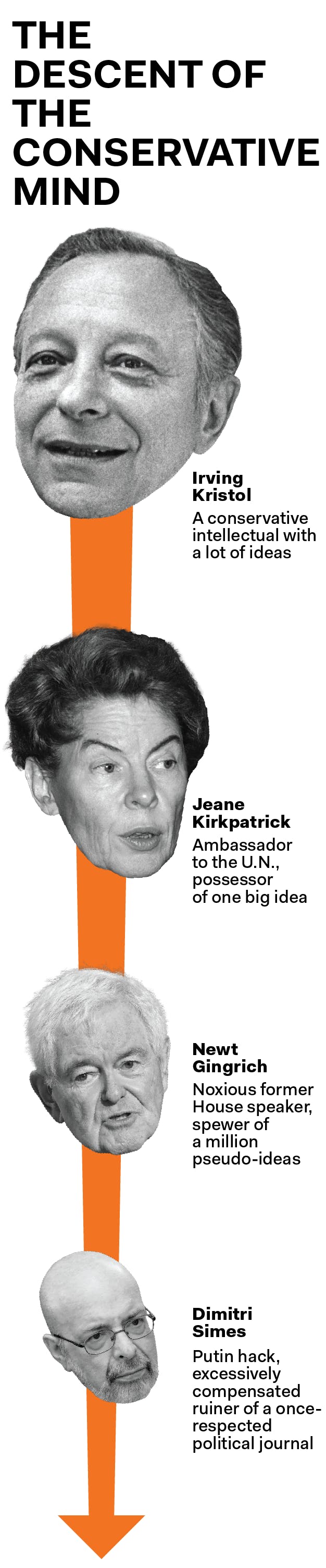

It’s a very far cry from July 1980, when Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan pronounced the GOP “the party of ideas”: supply-side economics, the impermanence of authoritarian regimes (argued by Jeane Kirkpatrick in her influential Commentary essay “DICTATORSHIPS & DOUBLE-STANDARDS”), the welfare trap, the Soviet Union as Evil Empire, and so on. Most of these principles are now obsolete or proved false, and even then they were mostly reformulations of earlier conceits. But the Reagan agenda occasioned lively arguments that Democrats, who’d gotten intellectually lazy from dominating policy debate during the previous half-century, often lost.

You see very little of that today. Instead, there’s a lot of name-calling. Republicans have graduated from tagging Democrats as “socialists” (which in the cases of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders and New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is true, though Sanders is actually a political independent who caucuses with Democrats) to calling them “communists.” Thus South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem, writing two years ago in The Federalist, marveled that “Georgia, of all places, could elect two communists to the United States Senate.” Noem was talking about Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff. A 2022 ad by the Georgia Gun Owners Inc. recycled the accusation, this time against Warnock and Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, making it evident that “communist” was being used as a code word for “Black.” In response, PolitiFact ploddingly affirmed that no, Warnock and Abrams were not communists.

Another insult Republicans have ushered into the mainstream of public discourse is “scumbag.” A quarter-century ago, it was news when Representative Dan Burton, an Indiana Republican, called President Bill Clinton a “scumbag” in an interview with the editorial board of The Indianapolis Star. People found this unacceptably vulgar because the literal meaning of “scumbag” is “semen-filled condom.” Representative Henry Waxman, a California Democrat, was so outraged that he circulated a letter about it among committee members. In those days, members of Congress simply didn’t talk like that.

What a difference 25 years makes. During his successful 2022 Ohio Senate race against Democrat Tim Ryan, J.D. Vance, the freshman Ohio senator, could scarcely get a sentence out that didn’t include the word “scumbag.” Hardly anybody noticed. Ryan, of course, was a “total scumbag.” Republicans who “listen to the donors more than they do to their own voters” were “basically scumbags.” The big tech companies were “a bunch of corrupt scumbags.” The entire country of Venezuela consisted of “scumbags” (though, to be fair, Vance meant mostly President Nicolás Maduro, who admittedly has a terrible record on human rights). Vance made “scumbag” his mantra to sound earthier and not-of-the-establishment to working-class Ohio voters. As the conservative writer Christopher Caldwell noted in The New York Times, the word “scumbag” was absent from Vance’s much-admired bestselling 2016 memoir, Hillbilly Elegy, which sought to bridge the same gap between Red and Blue America that Vance widened in his 2022 campaign.

The word “nihilism,” invented by nineteenth-century Germans and Russians, originally described a revolutionary’s idealistic rejection of outmoded beliefs. Friedrich Nietzsche fixed its present, more sour definition as a conviction that one’s beliefs and actions have no meaning or purpose. The earlier definition may help explain why contemporary political nihilists often claim to be ushering in a glorious new order. But ask this nihilist what that new order might be, and the answer is going to be gibberish. (A more colloquial synonym for nihilist is “bullshit artist.”) For about a century, the word “nihilism” has been associated with decline. The nihilistic turn of the GOP is very much a sign of the party’s broader decline. It didn’t happen overnight. Trump was the parasite, but the host had been weakening for decades.

For much of the twentieth century, it was a matter of dispute whether American conservatism had ever existed as an ideology. Lionel Trilling famously wrote in The Liberal Imagination (1950) that

the conservative impulse and the reactionary impulse do not, with some isolated and some ecclesiastical exceptions, express themselves in ideas but only in action or in irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas.

That’s pretty much the line Bell took in The End of Ideology, too. Bell dedicated only a single chapter to conservatism; the ideology with which he was more concerned, and the one he saw ending, was Marxism. Bell judged conservatism less an ideology than a pathology rooted in “the peculiar evangelism of Methodism and Baptism, with its high emotionalism” and “excess of sinning.” (Bell insisted it was mistaken to identify moral hysteria, as many still do, with Puritanism.) This evangelism explained what, to Bell, were the otherwise baffling McCarthyite witch hunts that had only recently ended.

The Trilling-Bell view of conservatism is today in disrepute, with scholars noting that it overlooked, among others, Friedrich Hayek, Russell Kirk, James Burnham, and Ludwig von Mises. Bell made only a single reference to Hayek and consigned Burnham to a footnote. But if conservative ideology was so easy for a brilliant scholar like Bell to ignore in a book titled The End of Ideology, that suggests it hadn’t penetrated the culture very far.

That started to change with the founding of National Review in 1955 and, later, the nomination of Barry Goldwater in 1964. Conservative ideology reached its summit with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. Republicans judged themselves representative of what President Richard Nixon had called the Silent Majority and what the Reverend Jerry Falwell now called the Moral Majority. The GOP retook, in 1980, not only the White House, but also the Senate, having not acquired a congressional majority in either house for 28 years.

Republicans’ competitiveness as a legislative party has lasted, and it has even spread, during the past decade, to state legislatures. But its intellectual renaissance did not. “Nearly as soon as Reagan left office,” Vanderbilt historian Nicole Hemmer writes in her 2022 book, Partisans: The Conservative Revolutionaries Who Remade American Politics in the 1990s, the conservative movement was “skittering away from the policies, rhetoric, and even ideology that Reagan had brought.”

The biggest reason for the change was the end of the Cold War. That weakened the Republican justification for a strong defense. A “Defense Planning Guidance,” drafted in 1992 under the hawkish Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, said the new primary purpose of military policy was “to prevent the re-emergence of a new rival.” But after that language leaked to The New York Times, the Republican administration of President George H.W. Bush beat a hasty retreat. A decade later, as Russian President Vladimir Putin started to consolidate power, conservatives split over whether he was friend or foe. Somewhat shockingly, that split persists now that Putin has crushed internal dissent and is waging a brutal war of reconquest against Ukraine. Today, even the GOP’s historic commitment to defense spending is up for grabs as Kevin McCarthy calls for $75 billion in cuts to the defense budget—one of many concessions he made to Republican members who opposed his becoming speaker. “Eliminate all the money spent on ‘wokeism,’” McCarthy told Fox News’ Maria Bartiromo. “Eliminate all the money that they’re trying to find different fuels and they’re worried about the environment.”

The rise and fall of the foreign policy journal The National Interest is a case study. Founded in 1985 by the neoconservative Irving Kristol as a forum for the hawkish interventionism then ascendant in Washington, it was acquired in 2001 by a think tank that had been created by former President Nixon after the breakup of the Soviet Union to advance the more cautious realist school favored by Nixon and Henry Kissinger. The think tank, which had been called the Nixon Center, changed its name to the Center for the National Interest, reflecting that its focus was shifted to publishing. The center’s president was Dimitri Simes, a Russian émigré and respected foreign policy expert who had been close to Nixon.

The National Interest retained influence as a source of views that were more eclectic than those in the 1980s and 1990s. But circulation dropped steeply while Simes drew an extravagant salary of more than $400,000. In 2016, Simes compromised the center’s independence (not to mention its respectability) by becoming a foreign policy adviser to the Trump campaign. He looked enough like an intermediary between Trump and Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia to draw attention in the Mueller Report. A redacted portion, later leaked to the Washington Examiner’s Steven Nelson, said Simes told Jared Kushner that the Russians possessed a recording of former President Bill Clinton having phone sex with Monica Lewinsky. In 2018, Simes became co-host of a public affairs show, Bolshaya Igra, broadcast on a Russian TV network in which the Russian government held a majority stake.

Inevitably, The National Interest started running articles favorable to Putin and Trump. In 2015, Maria Butina, who would later do jail time for being an unregistered foreign agent for Russia (and who last fall assumed office as a member of Russia’s State Duma), opined in the journal, “It may take the election of a Republican to the White House … to improve relations between the Russian Federation and the United States.” Putin himself penned a 2020 article disputing a resolution passed by the European Parliament that condemned the 1939 Hitler-Stalin pact and “efforts of the current Russian leadership” to “whitewash crimes committed by the Soviet totalitarian regime.” Two months later, Simes argued “THE CASE FOR TRUMP,” who showed, Simes wrote, “unusual courage” and “perseverance” while he was “subjected to the moral equivalent of daily waterboarding.”

Simes retired at the end of last year, allowing the journal finally to shed its embarrassing associations with Putin and Trump. But he left behind yearly losses of $1 million to $2 million in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2020, Politico reported, and a journal staff that had dwindled from 20 to about four. In January, The National Interest shut down its print edition to focus on the web. The GOP Cold War consensus that Russia was an “Evil Empire” was defunct even as Putin sought savagely to justify it.

Hawkish conservatives were able for a while to transfer Cold War fervor from Russia to the Middle East, and the 9/11 attacks gave them the political opportunity to wage war against Saddam Hussein in Iraq. But the rationale for that war vanished when it was discovered Iraq didn’t possess biological and chemical weapons. The war dragged on for eight unpopular years, and in 2018 a withering Army study concluded that “an emboldened and expansionist Iran appears to be the only victor.” When Trump ran for president in 2016, he claimed (falsely) to have opposed the war from the start. Today, there is no Republican consensus about who America’s enemies are, much less where we should draw a line with them. It’s a far cry from Reagan at the Brandenburg Gate thundering, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

On the domestic front, Reagan quickly discovered there was little public support for cutting government spending in any meaningful way. “People don’t elect Republicans to repeal the New Deal,” Representative Jack Kemp, a leading ideological figure on the right, conceded in 1985. The bulk of government spending was on defense and in the two biggest entitlement programs, Social Security and Medicare. Reagan had no appetite for defense cuts, and although he’d once scorned Medicare as “the soup kitchen of compulsory insurance” and proposed that Social Security be made voluntary, he recognized even before he entered the White House that these programs were immensely popular. Instead, Reagan confined his entitlement cuts to poverty programs, which were much smaller and didn’t have much of an organized constituency to defend them. Unable to cut overall spending very much, Reagan nonetheless pressed ahead with deep tax cuts, with the result that the budget deficit nearly tripled on his watch. That put to rest fiscal conservatism except as a blatantly partisan tool to use against Democrats, who have had a significantly better record on lowering the deficit than Republicans.

There are still tax cuts and deregulation, of course. If Republicans can be said to have any remaining principles, it’s probably those. But the advent of the anti-woke-corporate GOP wing complicates such blatantly pro-business advocacy. No one is ever going to believe the GOP is challenging big business in any serious way so long as it continues to cut taxes and slash away at regulations (as it almost certainly will do). But while Republicans play for working-class votes, we hear less GOP rhetoric praising the awesome creative powers of entrepreneurs and job-creators, and more about corporations going soft on race, sexual orientation, and the environment. Last December, a Republican staff report from the Senate Banking Committee accused the ”Big Three” asset managers—BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard—of using investors’ money to advance diversity hiring and better environmental stewardship. These, the Republican staffers complained, were “political movements unmoored from financial performance” and therefore intolerable.

New Right conservatism was premised to a great extent on the idea that the social fabric was torn to pieces by the tumultuous 1960s. But over time, this argument grew ever more difficult to make. Take crime. In a 1981 speech Reagan declared that a “thin blue line” (that, is, police) “holds back a jungle which threatens to reclaim this clearing we call civilization.” The backdrop to this racially charged remark was a crime rate that had been rising since the ’60s. Reagan lengthened prison sentences and introduced preventive detention. Democrats didn’t dare push back very hard, because their constituents were unhappy about crime, too.

But the national crime rate peaked in 1991 and then started dropping precipitously (for reasons that are still debated). By the time Trump entered office in 2017, the crime rate had fallen by more than half, divorcing tough-on-crime rhetoric from any discernible reality. When Trump spoke of “American carnage” in his inaugural address, he was criticized widely for being out of touch; even many Republicans had turned their attention to criminal justice reform. The following year, Trump ended up signing into law the First Step Act, which shortened federal prison sentences and initiated other reforms. A rise in the murder rate during the Covid pandemic later cooled GOP enthusiasm for sentencing reform, but crime remains well below levels endured during the 1980s.

In 1993, William Bennett, who’d been education secretary under Reagan and drug czar under George H.W. Bush, initiated under the auspices of three conservative think tanks a series of annual reports called The Index of Leading Cultural Indicators. In his introduction to the second edition in 1994, Bennett said that “the forces of social decomposition” seemed “impervious to government spending.” But within a few years Bennett had to give up the project, because too many of the indicators were improving (to add insult to injury, under a Democratic president!). Today, the divorce rate is nearly half what it was when Reagan came into office. The teen birth rate, which was already declining when Bennett began his series, cratered after 1990 and is now near historic lows, thanks of course to contraception and also some decline in sexual activity among younger teens. Welfare participation is down due to President Bill Clinton’s welfare reform, which imposed time limits on cash benefits. The high school graduation rate is up. Except for marijuana and vaping, adolescent substance abuse is down.

Other social trends that conservatives had condemned in the 1980s won wider acceptance. Homosexuality is today judged a nonproblem even by most Republicans, and a majority-Republican Supreme Court legalized gay marriage. Out-of-wedlock parentage is up, but it stabilized at around 44 percent starting in 1990, and anyway most Americans today have no objection to it. Marijuana is now legal in nearly half the states. To the extent conservatives still wage culture war on such issues, it is no longer with any pretension to being a “silent” or “moral” majority. Rather, their posture has become that of an aggrieved minority. Where once they argued “homosexuality is wrong,” today they argue “do not trample the rights of those few who judge homosexuality wrong on religious grounds.” A funhouse-mirror pluralism has become the refuge of bigots and reactionaries.

“The ideas that once defined the Republican Party have become unpopular,” Geoffrey Kabaservice, a historian of the GOP who’s vice president of political studies at the nonprofit Niskanen Center, told me. “I think there’s a general sense in the Republican Party that those ideas are unpopular so they can’t be advanced openly.”

The only part of conservatives’ social agenda from the 1980s that prevailed is the new legal sanction extended to all state bans or restrictions on abortion. But conservatism’s long-sought legal victory last year in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization made anti-abortion Republicans less inclined to address the topic rather than more. That’s because abortion bans are now no mere hypothetical, but a brutal reality in at least 13 states. The public isn’t pleased. Fully 62 percent of registered voters, according to a September New York Times poll, thought abortion should be “always” or “mostly” legal, and 52 percent said they “strongly oppose” the Dobbs decision. Overnight, intensity of feeling about the issue migrated from the antis to the pros.

After an early draft of Dobbs leaked in May 2022, the National Republican Senatorial Committee sent out a memo advising candidates on the issue. The first talking point was: “Abortion should be avoided as much as possible.” The NRSC meant the medical procedure, but that could just as easily have been advice on whether to address the topic. Almost none of what followed advised candidates on how to defend the decision; the bulk of the memo was about how to use Democrats’ opposition to the decision to make them seem extremist. Dobbs did more to limit Republican gains in the midterms than any other issue; in exit polls, voters cited abortion second only to inflation as the most important issue, and since then inflation has been receding. More than one-third of Republicans want abortion to be legal. The Republicans’ biggest policy victory in decades is their biggest political problem.

True, Republicans found a new culture-war target in illegal immigration. Immigration was a nonissue under Reagan, who signed a major (and pretty liberal) immigration reform bill in 1986 and boasted in 1989 that “anyone, from any corner of the Earth, can come to live in America and become an American.” But President George W. Bush foundered with his own Republican Party when he tried to pass an immigration reform bill in 2007, and under Trump it became an absolute bête noire. Here, too, the emphasis is less on articulating a coherent GOP policy than on accusing Democrats of favoring “open borders.” That’s because the political benefit of advocating specific immigration restrictions is a mirage, with GOP legislators ever fearful they’ll be accused of supporting “amnesty” if they favor anything short of mass incarceration for undocumented immigrants.

As recently as 2013, a post-election autopsy by the RNC despaired that “if Hispanics think we do not want them here, they will close their ears to our policies…. We must embrace and champion comprehensive immigration reform.” That didn’t happen, because the GOP was deadlocked on the issue. Then Trump ran an anti-immigration campaign in 2016 in which he made anti-Latino and anti-Muslim slurs that even fellow Republicans condemned—yet somehow won more Latino votes than Mitt Romney had in 2012, and more still four years later. Even so, Trump’s signature immigration policy as president—the separation of children from their parents at the border—was wildly unpopular. Republican politicians have concluded that their best course is to agitate against immigration while steering clear of any proposed practical solutions, especially within the legislative sphere.

January’s House floor fight over whether McCarthy would be made speaker was the culmination of Republicans’ nihilistic drift. Out of habit, some news accounts labeled McCarthy’s opposition a right flank, but the conservative Wall Street Journal editorial page observed that “the dissenters don’t have major policy differences with Mr. McCarthy.” Newt Gingrich, whose ascent to the House speakership in the late 1980s and early 1990s set that era’s standard for Republican opportunism, rejected during the McCarthy balloting marathon any comparison with his own rise to power. “We weren’t just grandstanders,” he told The New York Times’ Robert Draper. “We were purposeful.” Of the new crowd, Gingrich said, “Anything that takes longer than waiting for their cappuccino, I doubt they’re interested in.”

But the end of GOP ideology didn’t start with Matt Gaetz any more than it started with Newt Gingrich. It began with the real world’s refusal, starting in the 1980s, to conform to the heady ideas that Pat Moynihan praised Republicans for generating. Republican ideology had its moment. Then it reverted to the irritable mental gestures that Lionel Trilling observed in 1950. The only surprise is that it took four long decades to hit rock bottom.