“I spend a lot of time thinking about the next Congress.”

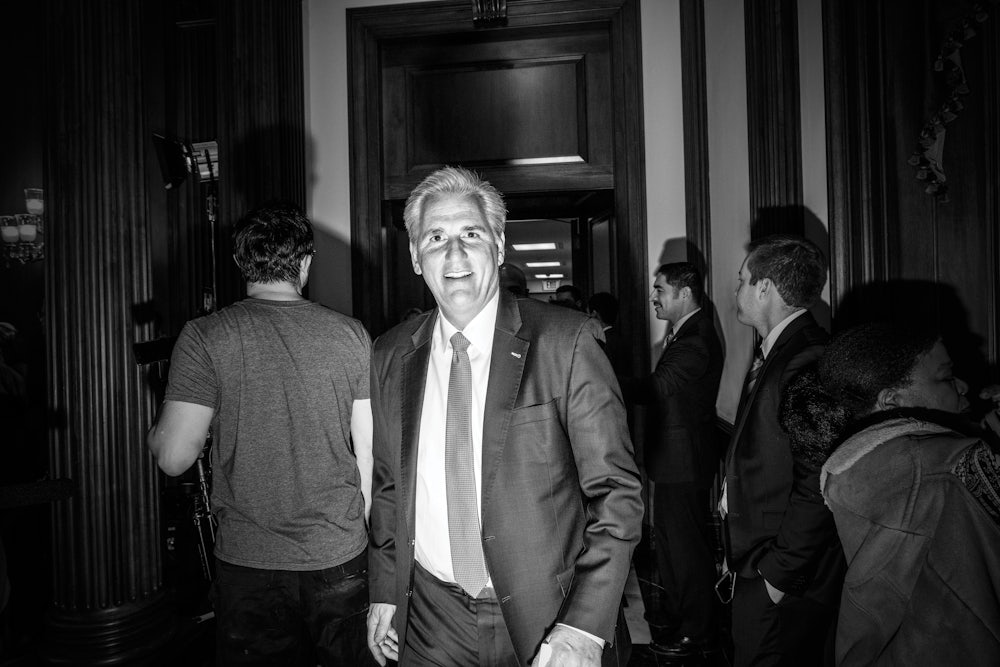

Kevin McCarthy, the Republican minority leader in the U.S. House of Representatives, meant this comment generally, rhetorically questioning how Congress could heal in an era of intense polarization—a somewhat ironic train of thought, given that the words came in a speech, delivered November 18, that was centered on attacking Democrats. But there was clear subtext: If Republicans won the majority in the House in the upcoming midterm elections, McCarthy could be the next speaker of the House.

McCarthy had begun speaking on the House floor shortly after 8:30 p.m. It was a Thursday night, and the House was about to cast a vote on the Build Back Better Act, President Joe Biden’s $2.2 trillion domestic spending package that later died in the Senate. Democrats in the House chamber knew that McCarthy would speak for longer than his technically allotted one minute: After all, he and all other Republicans were strenuously opposed to the bill. When it came to a vote the next day, no Republican would support it.

House Democrats settled into their seats, occasionally heckling McCarthy to challenge his more hyperbolic talking points. As the minutes ticked past, they became restless, waiting for the Republican leader to finish. The historic vote was the culmination of months of political agita among Democrats, requiring regular cajoling from Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Biden himself.

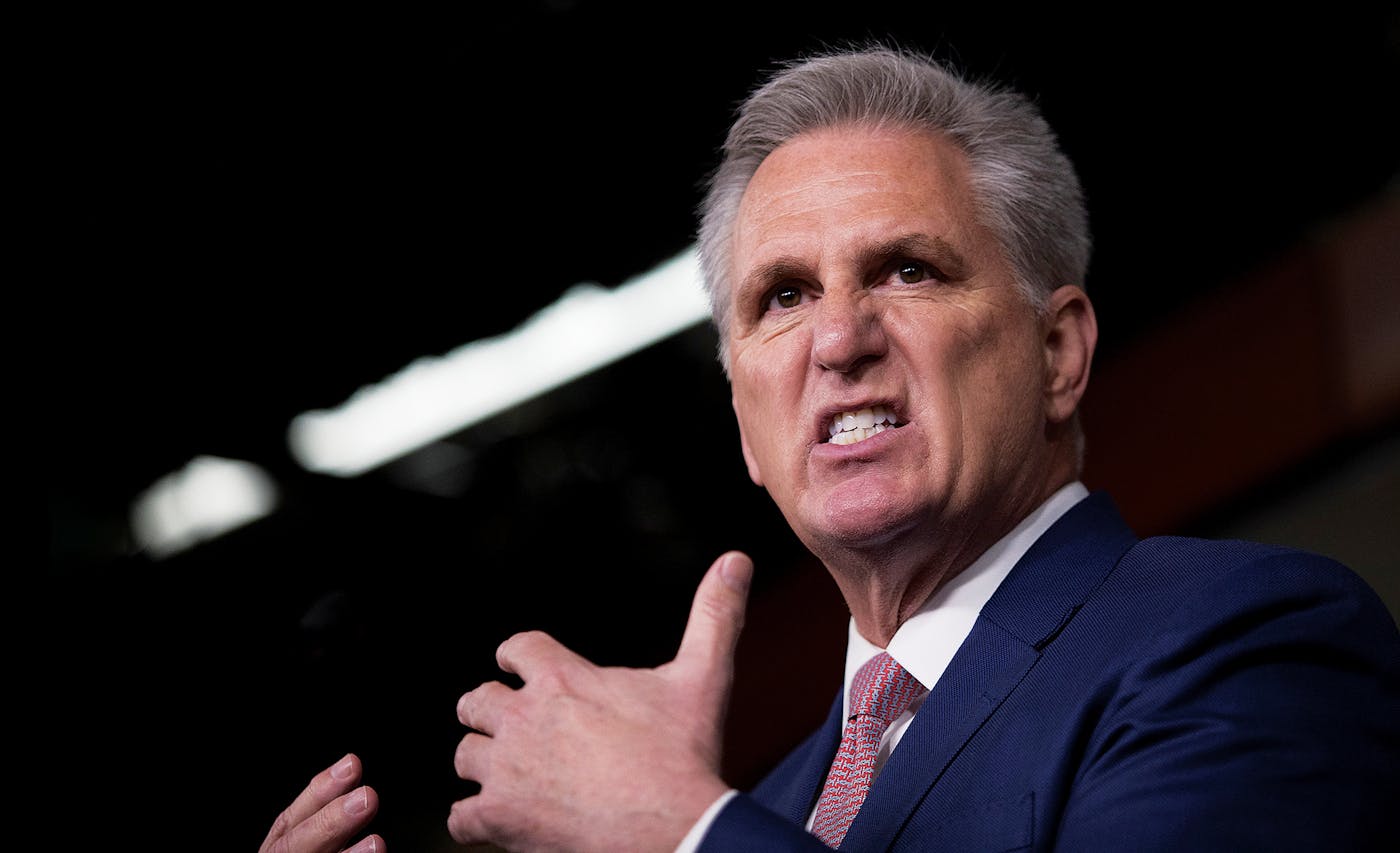

Meanwhile, a rotating cast of Republicans sat quietly around McCarthy as he spoke—close enough so that, to a viewer watching on C-SPAN, he would look like he was surrounded by supporters rather than the mostly empty chamber. McCarthy’s rambling speech was a grab bag of Republican talking points against the bill and Democratic policies in general, sprinkled with extended historical riffs and seemingly unrelated one-liners. His typically affable persona was largely discarded this night, his voice frequently rising to an angry shout, punctuated by emphatic pointing. Sweat glistened on his forehead as he confronted his Democratic colleagues, his expression one of apparent outrage as he occasionally turned to their side of the aisle.

He droned on about Ronald Reagan’s defense missile policy and outlined the history of a painting of George Washington crossing the Delaware River. He said that he would “love to debate Jim Crow someday.” He casually mentioned his personal friendship with Elon Musk, and excoriated the Nobel committee for never awarding President Donald Trump its Peace Prize. He slammed Democrats for being soft on China, asserted during a tangent on school choice that “there is no such thing” as baby carrots, and questioned whether McDonald’s still had a dollar meal. And he managed to hit all the right’s main talking points. “Inflation we haven’t seen in 31 years … gas prices … Thanksgiving … a border that in a few months breaks every record of the last three years combined,” McCarthy thundered at one point.

The Democratic voices that jeered so loudly at the beginning of his speech quieted as McCarthy continued to talk, the hours slipping past. One hour, then two, then three. Heading toward the four-hour mark, shortly after midnight, Pelosi came back onto the floor, murmuring to her members that they could go home. There would be no vote that night. The chamber mostly emptied of Democrats and bleary-eyed reporters alike, but McCarthy kept on talking. “I don’t know if they think they left, I would stop,” McCarthy said after most Democrats had exited the chamber. “I’m not talking to them. I’m talking to the American people.”

The American people were unlikely to be glued to C-SPAN after midnight on a weekday. McCarthy’s more immediate and important audience was his own Republican conference. He had already failed to earn the speakership back in 2015 after Speaker John Boehner was forced out, despite waiting in the wings; instead, that honor had gone to Paul Ryan, who grew so exhausted at holding the position under President Donald Trump that he had quietly retired in 2019. Now, finally, McCarthy’s moment was quickly approaching.

But he faced dissent from his right flank, and particularly those who believed his fealty to Trump was insufficient. McCarthy had also been subjected to a string of bad headlines in the preceding weeks. Earlier that month, after GOP leadership whipped its members against the bipartisan infrastructure bill, more than a dozen House Republicans ended up voting for it. More worryingly for McCarthy, Trump’s former chief of staff, Mark Meadows, had insinuated earlier that week in a pair of podcast interviews that the minority leader was not up to the job of speaker. In one, Meadows said he would give Republican House leaders “a grade of a ‘D.’” “You need to make Democrats take tough votes. You need to make sure that when you’ve got them on the ropes that you don’t throw in the white towel,” Meadows said.

McCarthy needed to prove to his conference that he was worthy of the gavel, that he was sufficiently supportive of Trump’s agenda, and that he was able to put Democrats on the defensive when necessary. His speech did not derail the vote on Build Back Better, but it did delay it by several hours, and it certainly annoyed Democrats.

McCarthy finished speaking at 5:10 a.m. on Friday, November 19. He had broken the record set by Pelosi for the longest speech on the House floor; she had barely cleared eight hours, while he had spoken for eight hours and 32 minutes. His tactic may have galvanized Republicans in the short term, but the matter of his assumed leadership over his caucus wasn’t resolved—just a few months later, McCarthy would be facing scrutiny again upon revelations of his criticism of Trump in the wake of the January 6 insurrection.

Throughout his speech, glimmers of personal truths revealed the underlying motivation for his taxing televised diatribe. At one point, McCarthy alluded to a rumor that Pelosi’s resignation was imminent. “I want her to hand that gavel to me,” he said. “I want her to be here.” And at around the midpoint of the speech, shortly after 1 a.m., he cracked a telling joke as Democrats were in the middle of changing their presiding officers. “Where’d the speaker go? Did you fall?” he asked, as the presiding officer’s chair temporarily sat empty. “Can I be speaker?”

McCarthy has represented his district in Central California since 2007. Although he has been in politics for the vast majority of his adult life, joining a congressional office as a staffer in 1987, he has never strayed from his hometown of Bakersfield. Once dismissed as a “Bakersfield boy” by former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, McCarthy has become an avatar of the city, and traces his values and his politics from its rolling hills.

The people of Bakersfield know how they are perceived by the rest of the state. Located at the southern edge of the arid San Joaquin Valley, Bakersfield has been uncharitably described as the “armpit” of the state, a reference perhaps to both its sweltering climate and its conservative politics. With a metropolitan-area population of nearly one million, Bakersfield would be the biggest city in dozens of states, but in California, it’s an afterthought, overshadowed by Los Angeles and San Francisco and three or four other major cities, and overlooked by the state government in Sacramento. “There’s a real sense of insecurity and a sense that you’re not appreciated, or you’re taken for granted,” said Richard Beene, a longtime local journalist, about the cultural ethos of the area.

Bakersfield is the seat of Kern County, one of the key destinations for desperate Okies fleeing the Dust Bowl. The city and its environs bear the legacy of that rugged, hardscrabble culture: Two country music stars of the mid–twentieth century, Buck Owens and Merle Haggard, were greatly influenced by their time in Bakersfield. “You could probably take Kern County and drop it right in the middle of Texas, and nobody would skip a beat,” said Mark Martinez, a political science professor at California State University, Bakersfield.

The biggest industries in Kern County are oil and agriculture, with many residents tracing their roots from migrant farmworkers—the county is 56 percent Hispanic. But it is a solidly Republican area, particularly given general statewide Democratic support for limiting oil production. “A lot of the Hispanic community works in oil, my family included. And so if that industry is gone, they’re going to be out of work. So they’re not necessarily going to vote for Gavin Newsom,” said Christian Romo, the chair of the county’s Democratic Party. Nonetheless, the Democratic Party is growing in the county, in part because of the influx of progressive urbanites priced out of Los Angeles and the Bay Area, county Democrats say. However, due to redistricting, McCarthy’s district became more Republican this year.

Bakersfield is characterized by wide, sun-drenched streets and hazy mountains barely visible in the distance. Its air pollution is among the worst in the country, second only to Los Angeles. Seventeen percent of the city lives in poverty, and it is the second–least-literate city in the country. But Bakersfield, a large city with a small-town mentality, is proud of its values and its industries, with a mindset familiar to any Trump supporter: The elites may look down on us, but we don’t like them either.

McCarthy was born on January 26, 1965, to Roberta and Owen McCarthy, the assistant city fire chief. A firehouse is like an extended family; to be raised with a family member in the fire service means to be absorbed into that close-knit community. “I think that that had a lot to do with developing his early core belief systems,” said Jeff Heinle, a retired city fire captain who was hired by Owen McCarthy in 1992. Kevin and his two siblings were raised in a middle-class neighborhood in a house with one of the few swimming pools on the block. He was tight end on his high school football team. McCarthy’s early mythology, a classic bootstraps-reliant Republican origin story, has been told and retold by him and others: Sometime in the mid-1980s, he won $5,000 in the state lottery and used it to open his own deli, putting himself through college at Cal State, Bakersfield.

The details and timeline of these events, even as related by McCarthy himself, are a bit fuzzy. But according to a 2018 Washington Post fact-check of McCarthy’s early entrepreneurial claims, the young community college student invested his winnings in the stock market, and then used those funds to open Kevin O’s Deli. This enterprise amounted to a counter and a refrigerator nestled within a yogurt shop owned by his uncle and aunt. After a short hiatus, he returned to college in 1987, which was the year that he also began working for the man who would define his career: U.S. Representative Bill Thomas.

He started as an intern that year and was later hired as a full-time staffer; he spent the next 15 years in Thomas’s employ. “He was a great worker, and I saw a lot of potential,” said Cathy Abernathy, a prominent GOP consultant who worked as Thomas’s chief of staff at the time. Even as he served in Thomas’s office, McCarthy rose to some national prominence, chairing the California Young Republicans in the mid-1990s and then the Young Republican National Federation from 1999 to 2001. He won his first election in 2000, to a seat on the Kern County Community College District Board. (This period was momentous in his personal life as well; McCarthy married his wife, Judy, with whom he has two children.)

On paper, the irascible Thomas was the polar opposite of his protégé. Where McCarthy is affable and friendly, Thomas was cantankerous; if McCarthy is the most popular man in a room, Thomas was the smartest. He was policy-oriented, becoming the chair of the powerful Ways and Means Committee in Congress. “[Thomas] always said, ‘I want to know more than a witness at a hearing.’ And he did,” said Abernathy. “When he bought a car, he didn’t just get that little booklet you put in your glove box, he bought books on every part in that car. That’s his thing. That’s not Kevin’s thing.” Richard Beene added, “Kevin is not as smart as Bill Thomas. He’s just not. He’s not as articulate. He’s not as smooth as Bill Thomas. But what he lacks there, he’s always made up in enthusiasm and connections.”

In 2002, McCarthy was elected to the California Assembly; less than a year later, he was elected its minority leader. This was likely in part due to his relationship with Thomas, who loomed large in state Republican politics. McCarthy was not a policy wonk like his mentor, but he had the amiability necessary to ascend politically, and his ability to build personal connections—not to mention his fundraising prowess—helped him to maintain that power. “Kevin understood how to connect on a member level, but he also understood how to connect on a personal level. And it was a sight to behold,” said Jim Brulte, who served as Republican leader in the state Senate while McCarthy was in the Assembly. Before McCarthy even got to Congress, Brulte told conservative commentator Fred Barnes that he would someday be speaker.

Thomas announced his retirement in 2006—after being term-limited out of his chairmanship of the Ways and Means Committee—and McCarthy was all but crowned his successor. (Thomas has since expressed disappointment with his former protégé, most recently labeling him a “hypocrite” in the wake of the January 6 insurrection.) McCarthy has won every subsequent election with relative ease. His popularity in the district varies; opponents note that the doors to his district office are always locked, and that his policy positions demonize immigrants when such a large portion of his district is Latino. Heinle praised McCarthy for his work with the Fire Department in erecting a September 11 memorial, but he argued that the minority leader has become more detached from his district since Trump took power. “That was a different Kevin. That wasn’t ‘my Kevin.’ You know what I mean? He’s changed,” Heinle said, referring to Trump’s declaration of McCarthy as “my Kevin.”

Bob Price, another longtime journalist in the area, noted that billboards critical of McCarthy had popped up in Bakersfield, and said his popularity had faded somewhat since the attack on the Capitol. “I’ve heard some grumblings, including some people that are actually close to McCarthy … who have been critical of him, people that in the past have been pretty much in his corner, and they’re questioning him,” said Price. “But are there enough of those people to threaten his seat? Hell no. Absolutely not.”

It would have been unsurprising if a junior congressman from an overlooked city—light on policy but heavy on relationships—had sunk into back-benching anonymity in the House. Instead, McCarthy, through glad-handing and charm, fairly quickly ascended out of congressional obscurity to minor prominence in the House Republican leadership circles.

Politicians can be more celebrity-obsessed than anyone. Even among that cohort, McCarthy sticks out. As he’s risen through the ranks of Congress, he has occasionally assumed the air of a starstruck kid from Bakersfield. In interviews, McCarthy has whipped out photos of himself with major political players, from the pope to the late President George H.W. Bush’s casket. “He’s absolutely the biggest starfucker in Washington. He’s so taken with someone who is a big name, whether it’s Elon Musk or a soap opera star. He loves to hobnob with celebrities. No one thinks the guy has any real ideology or real morals,” a longtime congressional reporter said.

Pete Souza, the Obama White House photographer turned professional troller of Republicans, recently shared a photo of McCarthy and the ostensibly hated former president. “Remembering that day in 2015 when Kevin McCarthy begged President Obama for his autograph,” Souza wrote on Instagram.

A common description of McCarthy centers around his vanity—he’s never been shy about touting his connections to, say, Elon Musk. His intellectual chops are mentioned less frequently. Politico published an opinion piece in early June wondering why reporters who believe McCarthy is dumb don’t say so outright, rounding up all the coverage of McCarthy over the years alluding to his lack of substance or any deeply held beliefs.

“He’s a person who got behind Trump early because he had no moral qualms with Trump, which doesn’t bode well for a Republican majority. Say what you will about Paul Ryan, at least what he had was an ethos,” the longtime congressional reporter quipped.

McCarthy has said that his reputation as a lightweight means that he is often underestimated. His occasional unease in public speaking may also stem from his overcoming a childhood speaking disability. While he may not have the policy chops of Thomas, his predecessor, McCarthy has been able to propel himself to power by leveraging personal relations and a particular acumen for fundraising. And even as some on Capitol Hill acknowledge his deficiencies, there is also a sense that McCarthy could not have gotten as far as he has without some canny political instincts. “You don’t end up where he is just being a total idiot,” a Republican staffer on the Hill said.

McCarthy has never been shy about his ambitions. In his book Young Guns: A New Generation of Conservative Leaders—co-written with Paul Ryan and former Representative Eric Cantor—the future Republican leader wrote that he was “determined not to be satisfied with being in the minority.” McCarthy would have to grin and bear the minority until the GOP, boosted by a wave of anti–Barack Obama Tea Party sentiment, enjoyed a 64-seat swing in 2010. McCarthy had helped secure this victory by traveling the country to campaign for Republican candidates; by the time McCarthy sought his later leadership position, he could point to the legwork he had done on multiple members’ behalf, and the donations he had helped usher their way.

By 2009, McCarthy was on the lower end of House Republican Party leadership as Cantor’s chief deputy whip. Cantor saw a “young energy” in McCarthy, according to a former congressional staffer. “He wasn’t, like, the ideas guy, but he did want to champion the ideas,” the former staffer said. “Eric and Paul saw an energy—a guy that could help take some of the wonkiness and make it accessible. Because Paul and Eric are both wonks, and he just isn’t.”

Every time he crossed the country during work trips, McCarthy carried an Almanac of American Politics, with its detailed entries on the history, demography, and even topography of every congressional district in the country. He worked with Cantor to recalibrate the whip team’s operation to better help vulnerable incumbents. In 2013 and 2014, Republicans were dealing with a wave of insurgent ultra-conservative candidates across the country. The politics of that cycle and the ensuing years weren’t a perfect fit for McCarthy, who has always preferred charm and diplomacy to the burn-it-all-down absolutist approach that was in vogue among conservatives at the time. Historically, McCarthy had not prized policy purity over dealmaking; a Los Angeles Times profile of McCarthy from 2003 noted that the soon-to-be Assembly minority leader was a “pragmatist” with moderate views on abortion.

Ironically, though, McCarthy benefited from the Tea Party in 2014 more than most. The vulnerable incumbents Cantor sought to protect ended up including himself: Cantor hadn’t been watching his rightward flank and lost reelection to a little-known conservative professor named David Brat, who focused his campaign on apocalyptic warnings about immigrants. Cantor’s loss meant McCarthy was next in line to become Republican leader after John Boehner retired, something McCarthy had always craved. Cantor’s loss may have also offered a valuable lesson to McCarthy, one that would be reinforced by Boehner’s later struggles with Tea Party Republicans: The conservative faction of the party is powerful, and leadership would ignore it at its own peril.

Since he was young and aware of the position, McCarthy aspired to be speaker. According to a longtime friend, way back when McCarthy was a congressional staffer, he would turn to him and say, “I want to be speaker.”

When Boehner retired in 2015, essentially forced out by the most right-wing members of his conference, it seemed as if McCarthy would finally achieve that dream. He’d spent years greasing the wheels of the Republican Party, and he was at the right place in order of succession. But the House Freedom Caucus, the small, newly formed bloc of unmanageable and ultraconservative Republicans, was divided on whether to oppose McCarthy and support someone else. Representative Raúl Labrador in particular felt McCarthy was not sufficiently conservative, according to a Freedom Caucus member with knowledge of the group’s internal discussions.

Even more foreboding for McCarthy, rumors of an affair with Representative Renee Ellmers, the now-former congresswoman from North Carolina who came into Washington as part of the 2010 Tea Party wave, were swirling, which spurred Representative Walter B. Jones to circulate a letter urging Republican leaders to substantiate they had not done anything embarrassing. (McCarthy and Ellmers have both denied the allegations.) McCarthy had also been damaged by one of the worst gaffes a member of Congress can make—that is, saying the quiet part out loud: He had boasted that the select committee investigating the Benghazi debacle had made Hillary Clinton’s approval ratings collapse.

The conservatives in the caucus began to demand promises that McCarthy knew he couldn’t deliver if elected speaker. His allies began to feel pressure back home about supporting him. Rank-and-file Republicans wondered how chaotic their caucus would be under a McCarthy speakership. In the end, McCarthy eventually withdrew from the running. “The conservatives didn’t trust him. He had rumors about a relationship with another member that were never substantiated in my mind,” former Representative Tom Davis of Virginia recalled. “But basically, they didn’t trust him. They thought he was too much of an operative, and I think he’s tried to overcome that over time.” At the time, Trump cheered McCarthy’s retreat, saying, “We need a really smart and really tough person to take over this very important job!”

In the end, and after much prodding from Boehner, Ryan became speaker as the compromise candidate. It looked as if McCarthy would stay in middle management for a political eternity. Ryan, after all, was the P90X workout devotee who was both conservative enough for the Freedom Caucus and sane enough for the more establishment Republicans in the chamber. He had long styled himself a “House guy,” so leading the body seemed to be something he would stick with for a long time.

That all changed with Donald Trump’s ascension to the presidency. Ryan and Trump didn’t quite vibe. McCarthy and Trump, on the other hand, did gel, in part because of McCarthy’s careful tending of Trump. He took this effort to extremes, even picking out cherry- and strawberry-flavored Starbursts for the president, after noticing during a trip on Air Force One that Trump liked them the best.

McCarthy’s allies and friends say that his political skill lies in his ability to identify who has power and cozy up to them. McCarthy saw that Trump would determine the future of the GOP and was more than open to sidling his political fortunes up to the president. It worked, to the extent any charm offensive works with Trump. He started calling McCarthy “my Kevin.” (McCarthy’s allies back home bristle at the insinuation presented by the phrasing of “my Kevin”; GOP consultant Abernathy insisted that Trump had only used that term because he had been looking for McCarthy in a room filled with multiple people named Kevin.) After Ryan announced he was stepping down as speaker and leaving Congress, Trump privately complained to colleagues that the Wisconsin Republican was dawdling in his exit, and that McCarthy should step in sooner, according to a Republican who talks regularly to Trump.

Publicly, McCarthy is oftentimes one of Trump’s most strident defenders. When Trump faced questions about his call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, which would eventually lead to his first impeachment, McCarthy said in an interview with CBS’s 60 Minutes that the “president did nothing in this phone call that’s impeachable.” That, and his numerous and virulent defenses of Trump against charges of working with Russia in 2016, represented a dramatic shift from a few years earlier when, speaking privately with fellow Republican leaders, the California Republican said, “There’s two people I think Putin pays: [Representative Dana] Rohrabacher and Trump.”

There has been no bigger illustration of McCarthy’s thinking process and motivations than around the January 6 mob attack on the Capitol. After initially denouncing Trump’s behavior in connection to the mob attack, McCarthy changed his posture, defending the president and trying to either minimize the importance of the January 6 committee or trip up its process. His gambit has been to side with Trump, pegging the committee as a liberal political stunt instead of a legitimate inquiry. He also refused to name anyone to the select committee after Pelosi rejected two of his five initial choices, a move that has been heavily condemned in recent weeks, including by Trump, as the committee’s public hearings have proved far more effective than most people anticipated.

For weeks ahead of January 6, McCarthy had been echoing Trump’s false claims that he won the election. The day after the 2020 election, McCarthy said at a press conference that Trump would continue to fight for his reelection “until all the votes legally cast are counted.” He predicted that in the end Trump would emerge the winner. In the days that followed, the Republican leader’s public comments about the election increasingly matched Trump’s false assertions. “President Trump won this election,” McCarthy said on Laura Ingraham’s Fox News show. “Republicans will not be silenced. We demand transparency. We demand accuracy. And we demand that the legal votes be protected.”

During the chaos at the Capitol on January 6, McCarthy was in close touch with White House aides and Trump himself. He had a panicked exchange with Cassidy Hutchinson, the aide to Mark Meadows who has since testified dramatically before the select committee investigating the insurrection. Hutchinson said that McCarthy excoriated her in a phone call after Trump’s rally speech preceding the attack, recalling that he said: “The president just said he’s marching to the Capitol. You told me this whole week you aren’t coming up here, why would you lie to me?”

As the rioters breached the Capitol and got closer to members of Congress, McCarthy, like other lawmakers, became more panicked. In a phone call, Trump told McCarthy that the rioters cared more about the election results than he did. McCarthy, according to CNN, shot back, “Who the fuck do you think you’re talking to?”

But hours after the rioters were cleared from the Capitol, McCarthy joined more than 100 of his House Republican colleagues in voting to overturn the election results.

For the briefest of moments after the insurrection, it looked as if McCarthy might lead the charge to remove Trump from office and sideline him from politics. About a week after the attack, McCarthy said during a speech on the House floor that “the president bears responsibility for Wednesday’s attack on Congress by mob rioters.” Privately, McCarthy was sounding even more aggressive. According to New York Times reporters Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns, he decried Trump’s conduct on January 6 as “atrocious and totally wrong” to other House Republicans in a phone call during the days after the attack. He told his colleagues that he would tell Trump that an impending impeachment resolution against him would pass, and the president would do well to resign.

But in the weeks after January 6, McCarthy drastically moderated his criticism of Trump. It’s not exactly clear why. By one account, Trump at one point reportedly called McCarthy a “pussy,” which McCarthy was made aware of. He undoubtedly also saw polls showing the base rallying around Trump. In late January, McCarthy traveled to Mar-a-Lago to try to repair his relationship with Trump. McCarthy had requested a meeting. He ended up taking a photo with the president, and Trump’s political committee described the meeting as “very good and cordial.” McCarthy’s about-face here was a cynical calculation of which way the wind was blowing. “He doesn’t believe in Trump, he doesn’t believe in Trumpism,” the former congressional staffer said. “He doesn’t believe in protectionism and all this election bullshit, but he feels like if he strays too far away from it, he will absolutely miss his chance to finally get the gavel, which is finally in his grasp.”

For most of the Biden administration, McCarthy has been laying the groundwork for his prospective speakership. When he’s had to deal with the fringiest elements of his caucus, McCarthy has opted against outright punishment. He almost always defers to the carrot instead of the stick. After Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene was found to have attended a white supremacist conference, all McCarthy did was give initial condemnations. Similarly, even though Representative Lauren Boebert was widely denounced for calling Representative Ilhan Omar a member of the “Jihad Squad,” McCarthy only released a statement saying he had talked with her, and she had apologized. Representative Paul Gosar’s tweet sharing a violent anime video of himself attacking Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was largely met with a collective shrug from GOP leadership. One of the few Republicans McCarthy has chastised, Representative Madison Cawthorn, earned the wrath of his colleagues in the conference only because he claimed Washington was a den of coke-filled orgies.

“He’s a consensus builder. He’s not a top-down manager. He’s not his-way-or-the-highway, and I think that is where the John Boehner-benevolent-dictator approach to leadership in the House would’ve fit in well in the 1970s or 1980s,” said ex-Representative Mick Mulvaney, a former Trump acting chief of staff.

Tepid responses—when responding at all—suggest that McCarthy is wary about angering any wing of the Republican Party. If he becomes speaker, that will make his job difficult. Historically, caucus leaders have disciplined members of their own party by taking away committee assignments or offering forceful punishments, a tactic employed by Boehner against Representatives Justin Amash and Tim Huelskamp. If McCarthy were to do that, it would contrast starkly with how he has behaved most of his political career; he is more likely to retaliate against Democrats for removing Greene from committees by doing the same to their members.

McCarthy’s propensity to play nice may be a vestige of his time learning from Bill Thomas, who served in Congress for 28 years. But Thomas served in a very different Republican Party, and a very different House than the one McCarthy is managing today. “Bill Thomas would tell you, ‘Back in the old days, we never did any of our fighting in public, we always did it in conferences.’ And I think Kevin watched Bill Thomas build these coalitions,” said Beene, the Bakersfield journalist. “[McCarthy] came up under one set of rules, and the rules have changed.”

Thomas Massie, a Republican representative from Kentucky who frequently clashed with Boehner, said he believed the leadership tactic of kicking members off committees was “inappropriate,” and he praised McCarthy for not taking that route. However, he acknowledged, “we’re in the minority, and it’s easy to be nice when there’s not much to lose.”

McCarthy’s conciliatory tendencies have served him well in some respects. Allies of McCarthy will point to his forging of a strong relationship with Representative Jim Jordan of Ohio, the bellicose Freedom Caucus leader and ranking member of the Judiciary Committee. Where Boehner and Ryan had an antagonistic relationship with the more extreme ends of the conference, McCarthy has cultivated relationships to ensure his standing with them, at least temporarily. “He doesn’t just know your name. He knows your spouse’s name. He knows your dog’s name. He knows your favorite athletic team. He knows what you like to drink or smoke or what candy you like. I mean, his mastery of the individual relationships in the conference is pretty impressive,” said Representative Tom Cole, the respected ranking member of the Rules Committee. “Beyond that, he’s just a hard guy not to like.” This camaraderie largely does not extend to Democrats—his sole relationship with Democratic leadership appears to be with Majority Leader Steny Hoyer—or even to some Republicans: He does not have a close relationship, sources told us, with Mitch McConnell.

But a few months before the November elections, some congressional Republicans are privately unsure if McCarthy even has the votes to become speaker. There’s almost always some last-minute alternative candidate who emerges in defiance of the front-runner. It’s likely a long shot will throw his or her hat in the ring, but congressional Republicans interviewed for this article also suggested that a more serious candidate like House Minority Whip Steve Scalise, McCarthy’s longtime deputy and occasional rival, would make a play for the speakership. Others have mentioned House Republican Conference Chair Elise Stefanik, who has spent the past year burnishing her credentials with the MAGA crowd.

And speaking of that crowd, there is the question of Trump’s blessing, which McCarthy does not quite have yet. Recently, Trump endorsed McCarthy for reelection but not specifically to lead the caucus—a point Trump has stressed in public interviews. That’s unlikely to deter McCarthy, who often responds to rejection with persistence and even stronger charm offensives. Republicans close to both McCarthy and Trump say the California Republican knows that his prospects to lead the caucus depend in large part on Trump’s backing, a point that Trump, too, is well aware of.

Some House Republicans have dismissed reporters’ questions about leadership as inside baseball, but even a sidestep can be telling. “I think we have a clear objective here as a conference: Go win seats and go create a majority to go stand up against Biden. And we need to have a conversation about what that’s going to look like, and then we’ll figure out our leadership structure,” said Representative Chip Roy of Texas. “Kevin’s a friend. I have a lot of friends in the conference. Let’s just keep marching forward and win in November.”

Which brings us to the big question: Assuming Republicans take the majority in November, and assuming they do select McCarthy as their leader, what will they do? Of course, Biden will still be in office, and Democrats have a much better chance of keeping the Senate than they do the House. If Republicans only hold one chamber in Congress, many of their votes will be little more than messaging items destined to die in the Senate (which will be true even if the GOP takes the Senate but is short of the 60 votes needed to break a filibuster).

One such vote could be on a bill to ban abortion on the federal level. In a press conference hours after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, McCarthy teased that House Republicans could vote on such a measure. When asked what abortion-related bills he would be willing to put on the floor if Republicans retake the House, McCarthy replied somewhat vaguely: “First and foremost, I believe in saving every life possible.”

There are also plenty of actions a Republican-controlled House could take that have nothing to do with legislation but would be designed to weaken Biden and the Democrats: investigating Hunter Biden, for example, or opening their own probe into the activity of the select committee investigating January 6. Republican leadership is already plotting to subpoena records from the committee, Axios reported, and GOP Representative Rodney Davis of Illinois in June announced that he had submitted a preservation request for all documents from the committee, setting up a future investigation by the House Administration Committee.

Davis lost his primary to fellow Representative Mary Miller, which in itself presents potential trouble for McCarthy: What will the Republican conference look like? Republicans who boast ideologies that were once at the fringe of the party are increasingly winning primaries, meaning that representatives like Greene and Boebert may be joined by more fellow ideologues. Miller, a freshman, has come under fire for appearing to praise Hitler and calling the overturning of Roe v. Wade a victory for “white life.” In West Virginia’s member-on-member primary, moderate Republican Representative David McKinley lost to Trump-endorsed Representative Alex Mooney.

If Republicans retake control of the House of Representatives in 2022, that will open the door for some of the fringiest lawmakers in the caucus to lead congressional investigations as well as for rabid interest in impeaching Cabinet members. “They will likely impeach [Attorney General] Merrick Garland,” predicted congressional scholar Norm Ornstein. “I think they want to hamstring the Justice Department and delegitimize it as much as they can.” And there is the strong possibility that they will move to impeach Biden over, well, something—the situation at the border is an oft-cited contender. Senator Ted Cruz and a number of House Republicans have said as much; McCarthy has said only that the Republicans wouldn’t impeach Biden “for political purposes,” which of course still leaves the door wide open to an impeachment on what McCarthy would tout as substantive, legal grounds.

Jordan (one of the two members Pelosi refused to put on the January 6 committee) will probably become chair of the House Judiciary Committee. Representative James Comer of Kentucky would take charge of the House Oversight Committee. Comer, in his current capacity as ranking member of the Oversight Committee, has already spearheaded a Hunter Biden–related attack, sending a letter to Biden’s art dealer, Georges Bergès, demanding correspondence between the Biden son and the White House, and asking Bergès about the prices fetched by the younger Biden’s canvases. Then of course there are his business dealings with China and his now-infamous laptop, discovered in a Delaware repair shop in 2020.

Republicans don’t reveal much about the type of investigations they want to see if they retake the House. It’s more of a long, rambling wish list. Retiring Representative Louie Gohmert, in a brief interview, said he hoped Republicans in the next caucus would investigate the FBI. Representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers, a former House Republican Conference chair, said there’s a “long list” of investigations she would like to see, before she ticked off “addressing gas prices” and looking into the “origins of Covid-19. Investigations of Big Tech, Big Tech censorship.”

Of the 10 Republicans who voted to impeach Trump, four are retiring, and three have lost their primaries (another, Liz Cheney, faces her primary on August 16). Few Republicans voted for bipartisan initiatives like the massive infrastructure bill or gun safety legislation. Some GOP members who have taken controversial votes have subsequently been punished: McKinley had voted for and defended the infrastructure bill, Davis supported a measure creating an independent commission to investigate January 6, and Representative Tom Rice voted to impeach Trump and had distanced himself from the president.

McCarthy has made inroads with the hard-right faction of his conference, as evidenced by his relationship with Jordan. But it may be difficult to wrangle a caucus filled with members who dispute the results of the 2020 election and often abhor compromising with the opposite party. This is not to say that cooperation across the aisle is impossible; just last year, Representative Kelly Armstrong, a hard-line conservative, teamed up with Democratic Representative Hakeem Jeffries on a bill to address sentencing disparities for crack cocaine, which garnered nearly 150 Republican votes.

But there is a conceivable future where Congress will need to raise the debt limit to avoid having the country default on its debts, for example, and McCarthy will have to contend with dozens of House Republicans who will not wish to bail out a Democratic president. What will McCarthy do? When asked what the House would be like under Speaker McCarthy, Representative Adam Kinzinger shrugged. “I don’t know. It’s going to be weird though,” Kinzinger said.

If he does become speaker, McCarthy’s famed propensity for maintaining power through personal relationships will be pushed to its limit. Thus far, McCarthy has been able to address any disagreements largely behind closed doors, and with limited consequences for offenders; Liz Cheney’s removal as chair of the GOP conference was perhaps the greatest punishment any Republican has received over the past two years. But he may face opposition from his right flank echoing what his two predecessors, Boehner and Ryan, contended with while McCarthy waited in the wings. Heavy is the hand that holds the gavel, particularly if the other hand is preoccupied with placating the Freedom Caucus and Donald Trump. McCarthy rose to the precipice of the speakership through charm and conciliation. His ascendance has been about making the people he needs for advancement happy—including Donald Trump. But being speaker is a job that requires confronting colleagues in not just the opposing party, but one’s own. That will be especially true for anyone leading the Republican Party, as its members lurch more toward extremism. When a moment of truth confronts him, will McCarthy have the backbone to choose the defense of democratic principles over the pursuit of partisan power? His choices so far indicate which course of action he will pursue.