The first day of a new Congress is usually a triumphant day for an incoming majority; a celebration of the changing of the guard as a mandate from the American voters to implement a new agenda. But Republicans, having only retaken the House by a much lower than expected margin, were overwhelmed instead by the brewing drama of electing a new speaker of the House.

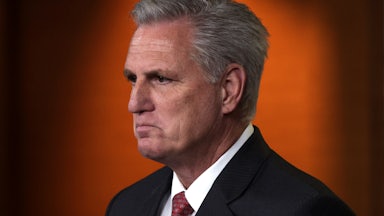

Kevin McCarthy, the Republican’s would-be gavel holder, had—as is customary—already moved into the speaker’s office on Tuesday morning. But he faced a series of brutal votes on Tuesday afternoon to be formally elected to the post. With every Democrat voting against him, McCarthy could only afford to lose four votes in his years-long quest to finally take the top job in the House. However, a recalcitrant group of conservative lawmakers steadfastly opposed him, forcing the first contest for speaker with multiple votes in a century. After three roll call votes, the House adjourned suddenly and with little fanfare, with McCarthy’s fate still uncertain.

McCarthy maintained a largely stoic posture in the first round of votes, looking straight ahead when members supported other candidates. His demeanor was tested by two subsequent rounds of balloting; by the third, he was often on his phone or fidgeting with his reading glasses. Although he received two standing ovations from his conference—one when he was nominated for speaker and one when he cast his first vote for himself—these showings of support were somewhat undercut by the noticeable minority of Republican lawmakers who remained sitting. In a contentious meeting ahead of the vote on Tuesday morning, McCarthy argued that he had “earned” the position of speaker, an argument that did not sit well with his opponents. Days of tension and disarray loom: While McCarthy may ultimately win the speakership, he has lost the appearance of control of his conference.

The show of dissension was hardly ideal for McCarthy, who if elected would need to preside over a fractious conference defined just as much by its vocal minority of contrarians—the “radical 2 percent” of Republicans, as defined by GOP Representative Kat Cammack—as its more mainstream members. Although he made a series of concessions to members of the Freedom Caucus over rules changes, including lowering the threshold for the motion to vacate the chair, many GOP representatives remained firm in their opposition to McCarthy. Nineteen Republican members voted for a candidate other than McCarthy on the first vote; Representatives Andy Biggs, Jim Jordan, Jim Banks, Byron Donalds, and Lee Zeldin received support. Only Biggs had been nominated for speaker, by fellow conservative Arizona Representative Andy Gosar, and Banks, Jordan, and Donalds voted for McCarthy. Zeldin retired from the House at the end of last year, but recemented his status with a better than expected run for the New York governorship.

The self-styled “Never Kevin” faction of Republicans then coalesced around Jordan—even after he gave a rousing speech supporting McCarthy. (Jordan has said he is disinterested in the speakership, and is about to achieve his goal of becoming Judiciary Committee chair.) On the third vote, the dissenters’ ranks grew from 19 to 20, with Representative Byron Donalds joining in the vote for Jordan.

“We’re basically at an impasse. So what are we going to do, have the same vote numbers for 10 ballots? That’s ridiculous to me, that makes no sense,” Donalds told reporters after the House adjourned. Donalds said he might be willing to change his vote again to support McCarthy, but “at the end of the day, you’ve got to close.” “We do not reward not being able to close deals,” Donalds continued.

But if that deadlock swayed Donalds, it frustrated other Republicans. Representative Don Bacon, a moderate, told reporters after the vote that McCarthy’s opponents “should be embarrassed by the start they gave us.” “We could have come together as a team. We have an agenda. But this is a self inflicted wound by these 19. They put themselves over the whole GOP and the whole conference. It’s a bad start,” Bacon said. He warned that Republicans may eventually need to negotiate with Democrats to get 19 votes, and “these folks are going to want something in return.” But Bacon argued that McCarthy would prevail: “It may take it may take some wheeling and dealing with other parts of our Congress to make this happen. But I do think it’s going to happen. As long as [McCarthy] stays steadfast, I think it’ll be alright.”

The 118th Congress entered with 434 members, with a vacancy from the death of Representative Don McEachin late last year. So while the Democratic leader, Representative Hakeem Jeffries, received the most votes of any candidate in the first round of voting, he did not reach the majority threshold to become speaker. Voting continues until one candidate reaches 218 votes, and McCarthy allies insisted on Tuesday that they were willing to stick it out in what was essentially a high-stakes game of chicken—that is, until it became apparent this wouldn’t come to an end any time soon. (The adjournment also means that the new House has not yet been sworn in, and so the 118th Congress is still comprised of representatives-elect.)

Emblematic of this initial determination was Representative Nicole Malliotakis’s vote for McCarthy, in which she added that she would support him “no matter how many times it takes.” Cammack similarly insisted to reporters on Tuesday morning ahead of the vote that “Kevin McCarthy will be the speaker of the House, and I don’t care if it’s the first ballot or the ninety-seventh ballot.”

But even some McCarthy supporters did not seem as confident of that outcome after the House adjourned. “I absolutely see a scenario where he gets he could get the speakership,” Representative Ken Buck told reporters. When asked if he believed that was the likeliest scenario, however, Buck replied: “No.”

This foretold a tedious day ahead: Every single one of the members present cast their vote in a roll call, meaning that multiple votes could take several hours. Even during the first vote, which took roughly an hour, several of the children of lawmakers who sat in the chamber with their parents became restless, murmuring and playing in the aisles.

Republican strategist Liam Donovan identified the Republican strife as “more of a reflection of underlying dynamics than a driver of them,” noting that “it’s not as though recent GOP majorities were well-oiled machines even with higher morale and a bigger cushion.” (See: Boehner, John.) The true tests of the functionality of a Republican majority, Donovan said, would be the must-pass items like funding the government and the debt limit. Indeed, the vast majority of House Republicans voted against an omnibus spending bill that skated through the Senate on a bipartisan basis just last month. If McCarthy can’t wrangle his conference to vote for him as speaker in one round, he may struggle to address basic housekeeping issues like avoiding a government shutdown and preventing the government from defaulting on its debts.

The grim determination of McCarthy and his allies was countered by the exuberance of Democratic members, who appeared almost inordinately gleeful for lawmakers who had fallen into the minority. Every single Democrat supported Jeffries, many of them noting their party’s unity in their votes in unsubtle digs at the other side of the aisle. (“They’re having a lot more fun than we are!” Buck joked after the House adjourned.)

Some Republicans downplayed the chaos on Tuesday morning. Representative Tom Cole, the chair of the Rules Committee, said that such “drama” was routine, and wryly suggested to reporters that it “makes you guys happy.” Representative James Comer, the incoming chair of the House Oversight and Reform Committee, said that it was “typical” for the Republican conference to have such dissension in its ranks. “Everyone has a strong opinion,” he said. Comer also insisted that his committee would “hit the ground running” with its planned investigations—even though the new House cannot be sworn in and committee work cannot begin until a speaker is elected.

Representative Pete Sessions, a McCarthy supporter, argued to reporters between votes that Republicans needed to listen to the dissenters, although he did acknowledge that the fight over the speakership “cost us prestige.” “I think you’re witnessing the maturity and the growth of individuals who feel empowered,” Sessions said. “I think that this is intramural scrimmage within the party that’s very serious. And schisms are there, and we know that, and we don’t lightly tap around it, and today it’s more exposing itself to what it is.” (Sessions told me after the House adjourned that “we’re getting ready to figure this out” and that “some, if not cooler heads, some adults will come into play.”)

But Representative Michael McCaul, the incoming chair of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, expressed frustration that the House could not kick into gear as long as the opposition lasted. “We have to get this done today so we can move forward, and we have to be united as a party so the story is not about Republicans fighting each other but what we’re going do for the country,” McCaul said.

Cammack issued fiery criticism to McCarthy’s Republican opponents on Tuesday morning. “This has nothing to do with bettering our country,” she argued about the dissenters. “I think our constituents back home expect us to lead, and they want us to be functional from day one.”

But as Representative Ralph Norman, an opponent of McCarthy, told reporters between the second and third vote, “There’s no magic about getting it done today.”

“We want somebody that will fight, we want somebody that will balance the budget, we want somebody that will go to the mat,” Norman insisted. “We need somebody that will shut the government down.”

* This article is about a breaking news event and has been updated.