In September 2022, a music critic named Anthony Fantano received a string of angry Instagram D.M.s from Drake. Fantano reviews new albums in short YouTube posts, in which he monologues directly at the camera, standing in front of stacked, cherry-red record shelves. In a recent post, he had likened Drake’s latest release, Honestly, Nevermind, to “a sad solo dance party.” “Your existence is a light 1,” the Canadian rapper clapped back, a reference to Fantano’s practice of rating records on a 1–10 scale. Uncharitable, perhaps. But the fact that Drake—a global superstar who is generally cagey toward journalists—bothered to inveigh against a critic at all spoke to Fantano’s status: He may be one of the few working music critics who can, in this day and age, be conceivably called a tastemaker. It was the sort of ego-first collision of artist and critic that’s in increasingly short supply.

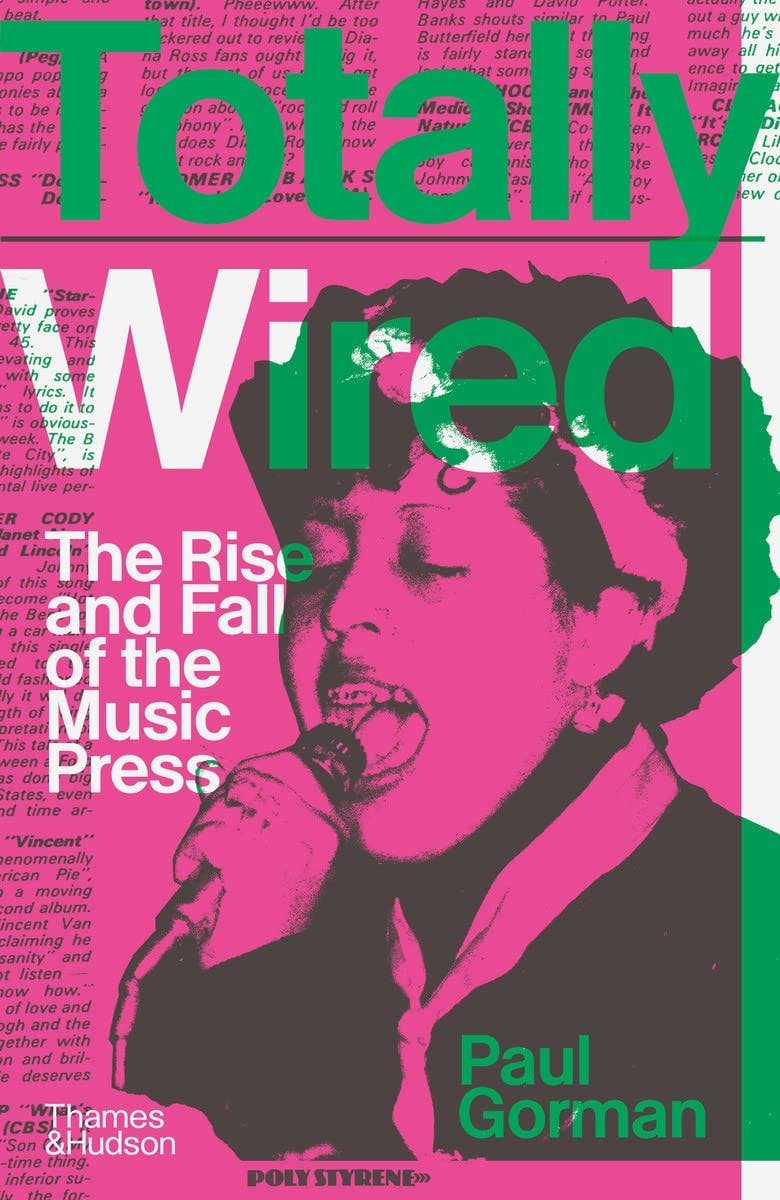

As Paul Gorman details in Totally Wired: The Rise and Fall of the Music Press, such encounters used to be more common. The rapport between artist and critic has historically ranged from affable to antagonistic to utterly bizarre. In 1969, in the pages of Melody Maker, Richard Williams accidentally reviewed the blank C- and D-sides of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s experimental Wedding Album, praising the “subliminal, uneven ‘beat’” of the blank records. The slip-up merited an enthusiastic response from the pop power couple, who said that “we both feel like this is the first time a critic topped the artist.”

Elsewhere, critics proved formidable thorns in their subjects’ sides. Legendary critic Lester Bangs once sat for an audience with his hero Lou Reed, only to end up calling him a liar with a “rusty bugeye” and “nursing home pallor.” Nick Cave, Gorman recalls, wrote the vitriolic “Scum” about NME writer Mat Snow (“A miserable shitwringing turd,” in Cave’s estimation). However petty these spats might seem, they spoke to the power of the music critic—or at least their ability to get under the thin skins of pop’s biggest stars. It was a complex, contested, and often symbiotic relationship that, in the words of Q magazine founder David Hepworth, served to make “acts seem exciting and larger than life, even when they weren’t.”

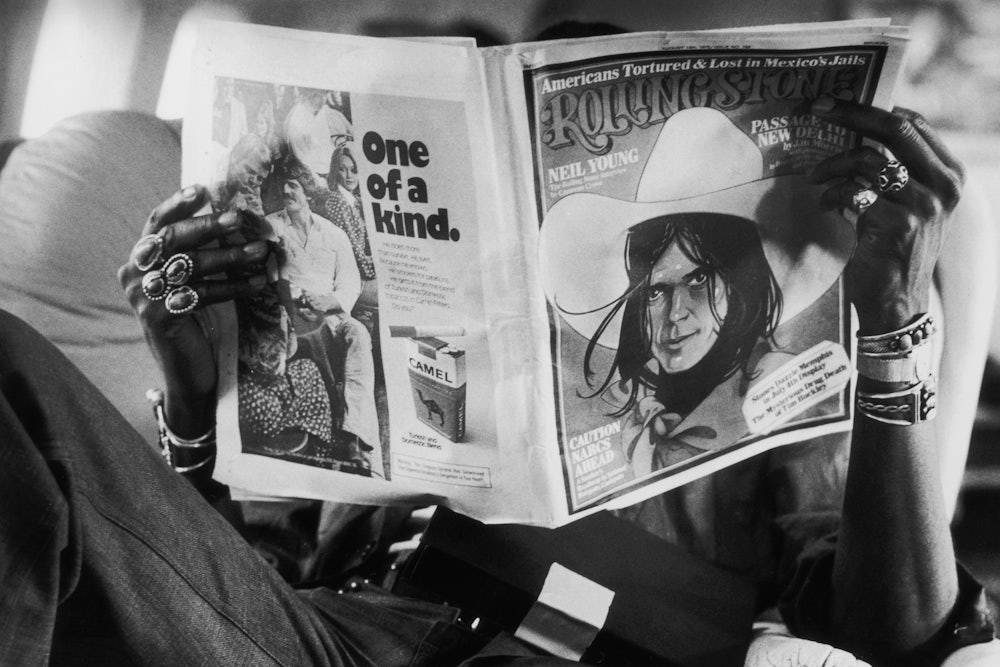

Totally Wired does a fine job recounting, and eulogizing, this heady heyday—a fertile era when magazines like Creem, Crawdaddy, Pressure Drop, Kerrang! and even boomer stalwarts like Rolling Stone served as a counterweight to the larger culture industry, rather than serving as just another subsidiary to it. From the early days of Melody Maker (whose first cover star in 1926 was English composer Horatio Nicholls) to the present (when Melody Maker has been defunct for two-plus decades), Gorman frames the popular music press as “one of the most potent breeding grounds in popular culture.” Snatches of white-hot prose make the case for him, and he fills the narrative gaps with dense stretches reciting the mastheads of different magazines at different points in time, like a precocious little kid who can list the name of every dinosaur. (“Among the staffers were Angus Mackinnon, New York correspondent Chuck Pulin, underground veteran Nigel Fountain, and Let It Rock and Sounds refugees Simon Frith and Idris Walters.”)

Gorman’s ability to rattle off these expansive rosters begs a different question: Could one fill out a book with the names of current critical tastemakers? And more pressingly, are such writers even able to make tastes and shape the culture at large? The long period of critical fertility that Totally Wired chronicles can seem almost unbelievable now. In hindsight, all genuinely cool cultural inventions feel like flukes—like a blowout party thrown while the parents are out of town. Is there any hope for such eruptions in the future? Or is a lively, engaged, tastemaking popular music press something that—as the “fall” of Gorman’s title assures us—has happened, in the past tense?

For as long as there have been records, there have been too many records. And the music press emerged to help separate wheat from chaff. In the early days, such determinations were largely corporate, and self-serving. Gorman’s book positions Melody Maker, which began as a monthly in London in 1926, as the first major music magazine. Its publisher, Lawrence Wright, used its pages to push sheet music for the latest dance hall hits by Horatio Nicholls, the so-called “Daddy of Tin Pan Alley.” Horatio Nicholls was, in fact, the nom de plume of Wright himself. “Nor for the last time,” Gorman notes, “was a music paper used to foreground the interest of its principals.” Subsequent rags, like Maker competitor Rhythm Illustrated Musical Monthly, featured articles promoting musical equipment manufactured by the same holding company that published the magazine.

In this openly commercial context, in which corporate newsletters passed themselves off as legitimate periodicals, a strange value emerged: authenticity. When British venues began imposing licensing restrictions against groups with saxophones—which, as Gorman writes, “were considered suggestive owing to the blowsy nature of their tone”—Melody Maker spoke out. Eventually, the Maker evolved from self-promotional circular to the vanguard of what another historian termed “raffishness and Bohemianism.” Syncopation and, yes, even “blowsy” tones came to Britain, as the Melody Maker made good on its name. And for the decades that followed, the music press did a fine job advocating for forms and styles—jazz, rock and roll, punk, metal, hip-hop—that initially affronted the institutional mainstream.

Gorman is less interested in the current state of music criticism than in the writers who exemplified the music press at its peak of influence. It’s an understandable focus. Writers like Richard Meltzer, Ellen Willis, Lester Bangs, Robert Christgau, and Nelson George rank among some of the finest, most incisive writers of the last century, in any medium. Like the music they so passionately championed (or, just as passionately, ragged on) their best critical writing has that whiff of freedom, of unadulterated possibility, that shocks the spirit back to life. Praising the Sex Pistols in a 1977 Village Voice article, Willis wrote that the British punk groups of the era “beamed my culture back at me in a way that gave it new resonances.” The very same could be said about Ellen Willis.

Their critical tastes and attitudes ranged. There were the eggheads, like Christgau, who proudly wore the honorific “Dean of American Rock Critics,” or Meltzer, whose book The Aesthetics of Rock reads simultaneously like an exemplar and send-up of academic literature. “How foolish could Nietzsche have been to cite Wagnerian orchestral music as the metaphysical equivalent of the power of nature?” Meltzer pontificates. “Obviously, Chuck Berry has found more immediacy in the melodiousness of rock and may devalue amoral ‘nature’ for amoral man.” (Nietzsche, it should be noted, succumbed to his various maladies more than a half-century before Chuck Berry implored Beethoven to roll over and play dead.)

Others abjured the brainy, the hifalutin, and the efforts to exalt rock and pop by taking it too seriously. Lester Bangs attempted to meet the music he loved on its own terms. His writing mimicked the speed-freak rhythms of the bands he championed. He was especially attentive to the ways in which culture conspired to drain human beings of their emotion and vitality, and wailed against it, even typographically. “IF THE MAIN REASON WE LISTEN TO MUSIC IN THE FIRST PLACE IS TO HEAR PASSION EXPRESSED,” he wrote, in all caps, about a Blondie record, “THEN WHAT GOOD IS THIS MUSIC GOING TO PROVE TO BE?”

At its best, Totally Wired is an ode to these writers. But while the book abounds with names (of magazines, their writers and editors, and the stars meriting coverage), there’s little in the way of connective tissue, theme, or analysis. In one chapter, Gorman mentions a 1986 NME cover story by Lucy O’Brien, provocatively titled “Youth Suicide.” The piece (well worth reading in full) analyzes the mid-’80s uptick in suicides, pondering how gloomy groups like Joy Division romanticized affectlessness and self-destruction. Gorman mentions the article was a favorite of Kurt Cobain, who took his own life in 1994. The implication—that an NME story may have shaped the Sturm und Drang, and maybe even the acute suicidal ideation, of the era’s most iconic rock star—is both gruesome and tantalizing, speaking perversely to the outsize impact of the rock critic. But Gorman dispenses with the idea as swiftly as he introduces it, content to dash off in a paragraph stories that otherwise merit a whole monograph.

Gorman likewise spends precious little time on how, and why, the popular music press collapsed. The “and Fall” bit promised by the subtitle is brutally abridged. In the epilogue, he dashes off a few suggestions: major titles like Rolling Stone being sold off to megacorporations, the relatively abbreviated lifespans of modern music acts, a general “music criticism malaise” that saw critics transformed into more generalized cultural journalists. Although each of these theories might merit a substantial investigation, Gorman seems content to float them out as trial balloons

Other forces are ignored altogether. There’s the ascent of P.R., which sees artists and their narratives largely guarded by a battalion of trained media flacks. The extended, intimate interview has been by and large supplanted by 20-minute “phoner” junkets, in which a musician repeats a series of prepared talking points for the benefit of a journalist whose copy (already 95 percent drafted by the time of the conversation) needs to be seasoned with some exclusive quotes.

And of course, cultural shifts that simply devalued the spirit of “sex, drugs, and rock and roll.” The macho chauvinism of ’60s or ’70s rock stars (or of music press editorial boards) doesn’t fly any more. To his credit, Gorman presents a good accounting of the rampant sexism, racism, and homophobia that often governed tastemaking at many music mags, dedicating a chapter to the “blatant misogyny” that permeated a supremely laddish industry. Now artists are more likely to earn press by speaking frankly about personal trauma, or sobriety, or their battles with depression. Fine talking points, but this turn to self-searching sincerity lacks the specific verve that made early rock music (and rock music writing) feel vital, and even a bit dangerous.

Likewise, music fandom itself has mutated. The aficionado turned critic, in the Lester Bangs mold, who exhibits a mania around holding their favorites artistically accountable, is a rare bird. Blind, militant devotion is now the de facto mode of enthusiasm. Pop stars don’t need critical interlocutors in a culture where “stans” (named after the unhinged superfan from Eminem’s 2000 single) volunteer to defend their idols’ virtues and patrol the discourse around them. (God help the poor sap who runs afoul of a pack of “Swifties” online.) These shifts in relations have (intentionally, I think) further diminished the role of the critic. Publicists (and even artists) once regarded critics as a necessary evil. Now they’re just unnecessary.

It’s not just that the rock (or rap, or pop) critic is obsolete. It’s that they have been made obsolescent, by a decades-long consolidation of media empires and influence. Music magazines slowly mutated into “lifestyle” publications. Criticism was flattened into “content.” Wheat and chaff combined into a slurry that publishers desperately tried to hock as the internet shrank ad revenues. The days of Rolling Stone or Crawdaddy driving the culture industry, instead of being driven by it, are over.

Gorman’s book is a funerary appraisal. I’m less pessimistic, especially as a new generation of critics are finding homes on YouTube, in boutique publications like Maggot Brain, or even the recently revived Creem, which relaunched in fall 2022 with a cheeky cover declaring, “Rock Is Dead. So Is Print.” Such publications will likely remain small-circulation affairs. But their very existence feels like a small triumph. Tastemakers may still emerge on YouTube, or TikTok, or other platforms where so-called “content” is created. And the increasingly narrow demographic of sickos who simply luxuriate in reading good writing is bound to dig Bangs, Willis, and Christgau in perpetuity. That street-slang-meets-grad-school-dropout quality of their writing is likely always to find an audience, even if the general public loses interest in Lou Reed, or the Sex Pistols, or the increasingly outmoded idea of “authenticity.”

Critics may be marginal, and pop stars more remote, alien, and P.R.-groomed than ever. But music critics will always have a place, so long as they can offer an incisive accounting of works, and personalities, and the trends that animate them. And maybe their very marginalization will bestow them with the sort of cult status enjoyed by the artists they evangelize—a cold comfort in lieu of a salary and benefits package, no doubt. If a music nerd with a passion for experimental death metal can get a rise out of one of the biggest stars in the world, all is not lost. Maybe for his next salvo, Drake can sample Nick Cave’s “Scum.”