It’s always tempting to read too much into midterm elections. In politics, clear metrics are often lacking—and that goes double in an era in which polling seems less accurate than astrology. By the time the dust settles, the punditocracy will agree: These midterms provided authoritative proof of some prior narrative that had begun to unspool months earlier—the country is souring on the War in Iraq, feeling the impact of the rise of the Tea Party, reflecting the power of the #Resistance. The votes are in, and our priors are confirmed.

The truth is that midterms are nearly as predictable as death and taxes: The party that controls the White House always loses and often badly at that. This has happened during every midterm election, with two exceptions: in 1934, when voters backed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, and in 2002, in the wake of September 11—in every other midterm election, the president’s party lost seats in at least one body of Congress. Losing lots of seats in Congress is, for the party holding the executive branch, practically fated.

People who write professionally about American politics should really have this framed somewhere. pic.twitter.com/3BoL9bjR8w

— Osita Nwanevu (@OsitaNwanevu) October 21, 2022

And so by Wednesday or Thursday, the Democrats will have lost the House and possibly the Senate. The next two years—at least—will be defined by bogus investigations, threats of government shutdowns (if not actual shutdowns), gridlock, and chaos. Will the House file articles of impeachment against the president? This is probably a question of “when, “ not “if.” But Democrats have been staring down this eventuality for some time. Democrats have had their successes and their failures over the past year. Could they have done more to mitigate the damage? It’s the same question Republicans asked themselves after the 2018 election, and the answers are just as elusive. Suffice it to say, try as you might, you’re going to lose seats in the midterm elections. Probably a lot of seats.

Following the predictable results will be the predictable protracted fallout, in which various interest groups and ideological factions will demand that the party could have escaped its fate—if it had only adopted their own set of policy preferences and messaging quirks. On Monday, the centrist Third Way got a jump start, releasing a memo warning that the Democratic Party’s brand is toxic. “If Democrats manage to hold on to the House and Senate, it will be in spite of the party brand, not because of it,” the memo reads. Sure, why not? But what to do? Why, adopt the milquetoast pro-corporate messaging pushed by Third Way, of course!

“Despite a roster of GOP candidates who are extreme by any standard, voters see Democrats as just as extreme, as well as far less concerned about the issues that most worry them,” the memo continues. “Democrats are underwater on issues voters name as their highest priorities, including the economy, immigration, and crime.… Compounding these problems, a majority of voters (55%) describe Democrats as preachy and 53% say the party is ‘too woke.’ And while 54% call Republicans ‘too extreme,’ a strikingly similar 55% of voters say the same about Democrats—with 59% saying the party has gotten more extreme in recent years. A super majority (61%) of voters say Democrats are too beholden to special interests.” (Third Way is funded by a host of corporate interests.)

This is something that you will undoubtedly hear a lot as Democrats lick their wounds following the midterms: The party is simply too woke, too progressive. It’s lost touch with white working-class voters. It is in the thrall of its activist wing. It cares too much about policing speech and not enough about pocketbook issues. This is more or less what the party’s centrist wing has been saying for as long as anyone can remember, and somehow it’s not enough that the party’s standard-bearer is a nigh-upon-octogenarian centrist who remembers the era of working hand in hand with segregationist conservatives with fondness.

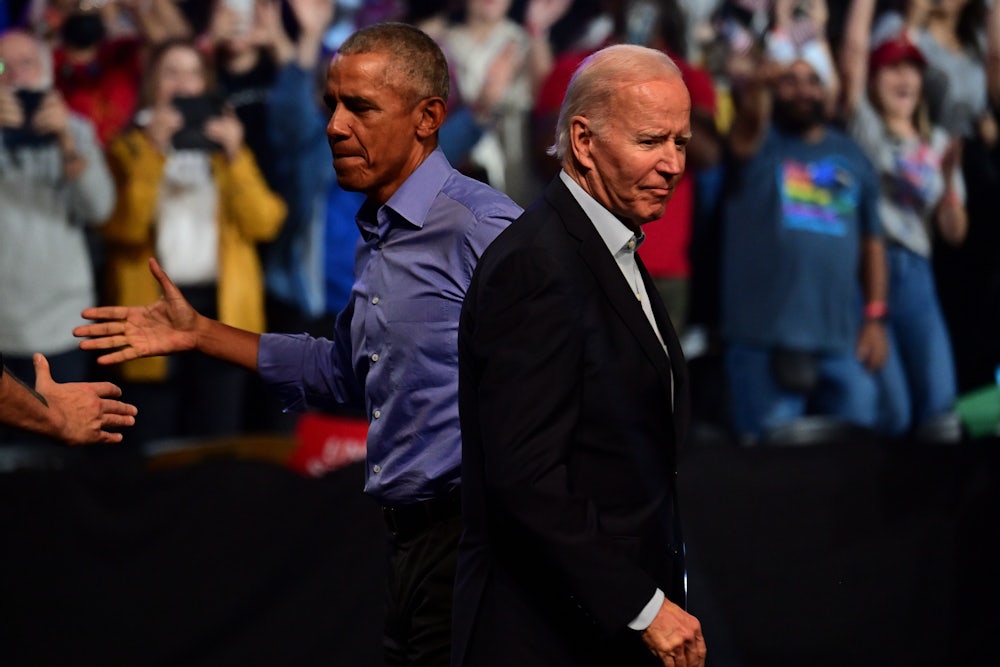

Naturally, once you start scratching the surface, it becomes hard to discern what, if anything, from the perspective of Third Way, went wrong with Biden and the Democrats’ actual approach to governing. The Biden administration and congressional Democrats have governed just as Third Way would want Democrats to: A bipartisan infrastructure bill, a vastly reduced spending bill hat shrunk the deficit—there is tsk-tsking about student loan relief, but that was, nevertheless, means-tested and relatively modest. The entire Democratic Party has come out against “Defund the Police,” a slogan (and policy) that virtually no elected Democrat supports. Former President Barack Obama regularly chides activists for being too focused on political correctness. Republicans have, nevertheless, relentlessly painted the party as being fixated on freeing criminals, defunding the police, and gender in youth sports (despite the fact that it’s the right that has spent the last year working itself into a lather about largely hypothetical questions about trans athletes). This leaves the door open for critics inside the Democratic Party tent to criticize “branding” and “perception.”

One could just as easily argue that Democrats will rue not having gone far enough when they—narrowly—controlled the White House and Congress, not the other way around. Expanding student loan relief could have been a way to lock in younger voters, many of whom are skeptical of the party’s ties to corporate interests and its lack of ambition. Similarly, the opportunity to do more to fight climate change—an existential threat—may have passed when Build Back Better was pared down. The expanded child tax credit did wonders in fighting child poverty before it was allowed to expire. And numerous measures to shore up voting rights died on the vine because there weren’t enough Democrats in the Senate willing to put their voters ahead of the Senate filibuster. Would Democrats have passed a more robust, progressive agenda if there were more of them in Congress? Maybe. With thin margins, they mostly governed with a series of modest, means-tested measures.

Democrats are suffering with voters on economic issues in large part because of inflationary circumstances that are largely out of their control. Still, they missed some opportunities: The message adopted by both Biden and Bernie Sanders—that inflation is being driven by corporate interests—is a winning one and would have been more effective if paired with a policy initiative aimed at corporations that are jacking up prices. There’s a strong argument that voters want to see proof that Democrats care about their economic well-being and that the right has successfully weaponized “wokeness” as proof that the party spends most of its time fretting about arcane social issues.

It’s abundantly clear that voters have an idea about the Democratic Party that’s out of whack with reality—again, the result of a remarkably successful branding campaign by the right pushed through its media/propaganda Wurlitzer. It’s hardly self-evident, however, that the antidote is to adopt conservative positions on those issues (or on immigration, for that matter), to make tactical retreats on treating trans people with basic human decency, or to adopt restrictive immigration policies. No matter how far Democrats are willing to indulge in rightward repositioning, the message from the right will always be that it’s not far enough.

It may be hard to swallow, once the votes are counted, but a sad fact is that Democrats have done quite a bit to mitigate their midterm damages. Dealt a bad hand—a ravaging pandemic, inflation, a successful Republican smear campaign around wokeness, a seemingly imminent global economic collapse, high gas prices (and the fact that Saudi Arabia refuses to increase gas production, likely in an effort to aid Republicans)—Democrats made a strong argument that they were responsible stewards, that Republicans would destroy American democracy, and that, in the age of book bannings and Dobbs, they were the country’s actual party of freedom.

This was part of a core message that, combined with some fortunate legislative luck and a few cagey political moves, briefly put wind in the sails of Democrats against the odds. The momentum didn’t last; a “message” on its own is not going to shatter the rough reality of inflation or high gas prices. Even during the period of time when Democrats seemed on the upswing, there was never a moment when it was likely they might hold onto their majority in the House of Representatives. But this is nothing shocking—that’s just pretty much how the midterms go. Democrats won’t have to carry the weight of electoral history into the next election cycle. They can choose, however, to carry with them the same ideas and energy that briefly made it look like they might somehow defy that history.