Even now, the glories of Election Night 2022 shimmer in memory as smug predictions of a first-term curse afflicting Joe Biden and the Democrats took it on the chin. The Senate was saved with every Democratic incumbent reelected, and John Fetterman victorious in the Land of Oz. Election deniers and insurrectionists were routed from Phoenix to Philadelphia. Even with the House, the Democrats could rightfully snicker as the widely anticipated Republican red wave crested during pundit roundtables on cable TV in October and by Election Day netted the GOP a paltry nine seats.

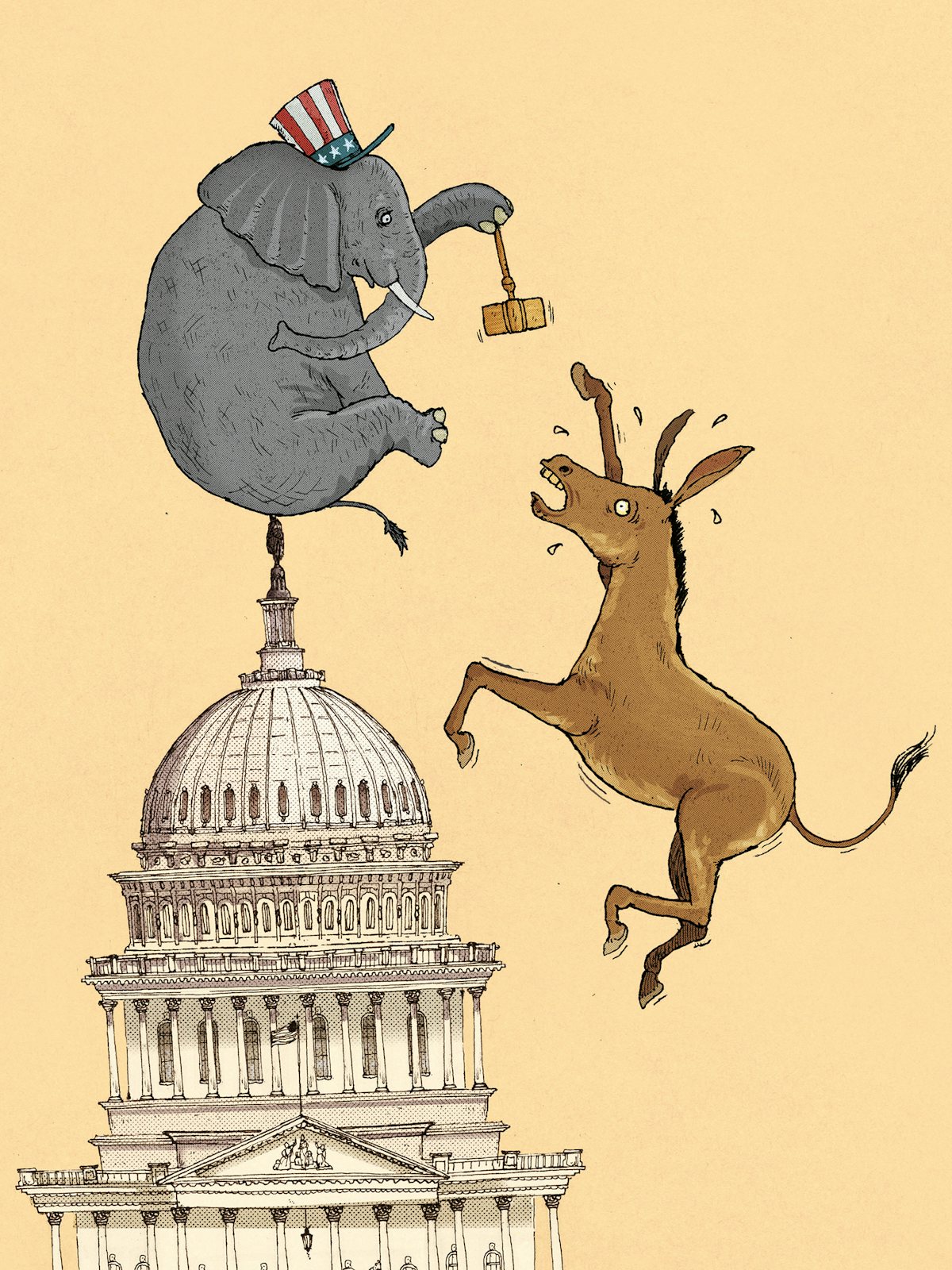

But as fragile as Kevin McCarthy’s majority may be, and as craven the compromises he had to make to become a pip-squeak speaker are, it is still a majority. And the closer you look at the election returns in the House, the more tragic that outcome becomes for the Democrats.

It didn’t have to be this way.

Although almost no one realized it at the time, the 2022 elections for the House were the Capitol Hill version of George W. Bush versus Al Gore. Even by the standards of close elections, 2022 was off the charts. An analysis by Jacob Rubashkin in early December for the political tip sheet Inside Elections found that just 6,670 votes spread over five House districts would have kept the Democrats in the majority. (Final counts have changed that number to 6,675). For math mavens, that works out to be 0.006 percent of the more than 107 million votes cast in House races. According to Rubashkin’s tally, 22,378 of these votes in the right places would have prevented the Republicans from picking up a single seat in the House. So we are not talking about a normal election—this was the Democrats losing on a wild pitch in the tenth inning of the seventh game of the World Series.

Many discussions of the narrow defeat of the Democrats pivot around redistricting. Had the courts thrown out Ron DeSantis’s GOP gerrymander in Florida and kept the lopsided pro-Democratic mapping in New York, the Republicans would not currently control the House. But even after the final 2022 district lines were set in stone, the Democrats still had a path to a 218-seat House majority. Overly fixating on redistricting obscures how agonizingly close the House Democrats came anyway and discourages examination of what the Democrats in key districts might have done differently in the quest for victory. “The idiosyncrasies of this election are so intense,” Rubashkin said, “we are going to be talking about them for some time to come.”

Perhaps the weirdest aspect of 2022 was the way that partisanship played out. For more than a decade, it has been an article of faith in politics and journalism that elections have been nationalized with local factors minimized. That helps explain why last fall so many political handicappers mistakenly extrapolated from such national numbers as Joe Biden’s dismal approval ratings to overconfidently forecast a coming Republican revolution.

But in 2022, House elections didn’t march in partisan lockstep across the nation. Depending on the state, districts moved sharply either toward or away from the Democrats. Brad Komar, a top strategist for the House Majority PAC (a leading Democratic independent expenditures group affiliated with the party’s House leadership), pointed out, “This was not a parliamentary election, where you win every seat that was 8-plus points for Biden in 2020 and lose every seat that was 4-minus for Biden. It was completely seat-by-seat.” It was almost as if Biden’s numbers and national polling didn’t matter. What seemingly counted far more—and this may be a hangover from the importance of statewide reactions to the pandemic—was the popularity of individual governors and other local factors. Gretchen Whitmer helped fuel a Democratic landslide in Michigan, while Kathy Hochul’s underperformance in New York may have cost her party four House seats. Komar, who is one of the Democratic Party’s leading experts on House races, added, “You can’t stress enough what a total break this election was from the Trump era and the statewide 2021 results in New Jersey and Virginia.”

Democrats may have been barely dampened by the red wave. But still, they should be haunted by the if-onlys. With 6,675 more votes, Hakeem Jeffries rather than Kevin the Spineless would be House speaker. The always jacketless Jim Jordan would not be chairing the House Judiciary Committee as he prepares to go Full Metal Jacket in foaming over and fomenting trumped-up Biden scandals. Marjorie Taylor Greene would still be ostracized rather than becoming (yikes) a Republican power player. With 6,675 more votes, the January 6 committee would still likely be issuing subpoenas, and the risk of the nation defaulting on its debt because of GOP temper tantrums and fiscal illiteracy would be minimized. On top of all that, the Democrats’ added fifty-first seat in the Senate (John Fetterman) diminishes the sometimes-say-no power of Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. As a result, the Democrats with a House majority could have kept the conveyor belt of meaningful legislation running to the president’s desk. Had the Democrats gotten a few more breaks and made a few more smart moves, the House of Representatives would be a functioning legislative body today rather than an international embarrassment.

There is no single reason why the Democrats failed to retain their House majority. Ideally, Democrats in key races should have raised more money, and the national party groups should have made letter-perfect targeting decisions. But no one in politics is omniscient, despite the tenor of TV talk shows. In fact, speculation about alternative realities can only carry you so far. “These elections aren’t science experiments where you can run them over again with different factors,” said Kyle Kondik, who analyzes House races for Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia.

But it is instructive for 2024 and beyond to understand why the Democrats so narrowly missed in so many races. Beyond money, the explanations include ill-advised strategic decisions, cookie-cutter attack ad campaigns, overly pessimistic polling, and a failure to seize opportunities. Here are tales of eight congressional districts (from the New York City exurbs to California’s Central Valley) where the House was lost. Had the Democrats won just five of these races—all decided by fewer than 6,000 votes—Joe Biden could effectively govern for the final two years of his first term. So, look at these stories as a political tragedy in eight acts.

Colorado-3: The Impossible Dream

Democratic dreams of defeating pistol-packing Lauren Boebert on the state’s rural Western Slope seemingly died with redistricting. On paper, the new map made the district unwinnable in 2022, since Donald Trump had carried it by 8 percentage points in 2020. The Cook Political Report rated the district “Solid Republican.”

Democrat Adam Frisch, a former Aspen city councilman, tried to run a stealth campaign against Boebert, calling himself a “conservative businessman” and attacking the incumbent for offering nothing more than “angertainment.” Boebert responded in scattershot fashion with ads that attacked “Pelosi’s lying liberals” and claimed that her rival’s “politics may work for Aspen ... but Adam Frisch is bad news for rural Colorado.”

In addition to the new district lines favoring Boebert, money was a determining factor here: Boebert ($7.1 million) badly outspent Frisch ($3.9 million), according to data from Open Secrets. And the money differential was driven by what was in many ways the real deciding factor in this one—the sense among Democrats that this just wasn’t going to be a competitive race. “So many people bought into the myth that the first election under a Democratic president would be a disaster that it was hard to raise money,” said Colorado-based Democratic consultant Jennie Peek-Dunstone. “Adam’s biggest Achilles’ heel was that nobody thought that the race was winnable.” Even an early October public poll showing Frisch within 2 percentage points failed to dent the skepticism about a Democrat’s chances in a Trump +8 district.

It is difficult to fault the national Democratic groups, which had to prioritize winnable races, for not spending any money to defeat Boebert. “Had the Democrats put more money in behind Frisch, it would have forced Boebert to spend more money,” said Rick Ridder, a Denver-based strategist who advised a small independent expenditures effort supporting Frisch. “He snuck up on her.” Aggressive national spending might even have had a paradoxical effect: It might have hardened the partisan lines in the race and made it tougher for non-MAGA Colorado Republicans to vote for a Democrat for Congress.

The context here is that, in recent years, Democratic donors have squandered hundreds of millions of dollars on impossible races. Amy McGrath raised a staggering $94 million to lose a 2020 Kentucky Senate race to Mitch McConnell by nearly 20 percentage points. This time around, House candidate Marcus Flowers hauled in $16.3 million ($13.3 million of which was in small contributions), mounting a symbolic challenge to the MAGA-mad Marjorie Taylor Greene in Georgia, which he lost by nearly two-to-one. It is agonizing to imagine what Frisch could have done with a fraction of the money wasted on the unwinnable Greene race in Georgia. A few more Frisch positive ads—reminding voters on the Western Slope that they had an alternative to someone whose politics are deranged—would have saved the nation (and, yes, the House Democrats) from having to endure four days of Boebert’s self-indulgent antics during the speaker fight.

Losing Margin: 546 votes.

California-13: When Washington Consultants Pull the Strings

This agricultural Central Valley open-seat race (which Democratic incumbent Josh Harder abandoned to run in an adjacent district) was the mirror opposite of Colorado-3. A district that Biden carried by 11 points was, despite the presidential margin, nationally recognized as a key toss-up race. But while this far-from-wealthy district may have looked exciting to national political handicappers, there was little local money available to either party. As a result, candidate spending by Democrat Adam Gray, a member of the state assembly, and Republican John Duarte, whose family owns one of the largest agricultural crop nurseries in the country, was dwarfed by the investments by national party groups. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and the House Majority PAC spent $6.5 million on behalf of Gray, while the Congressional Leadership Fund, associated with Kevin McCarthy, countered with $7.1 million on the Republican side. All in all, candidate spending accounted for about one-quarter of the money spent in this majority Latino, blue-collar district that The Cook Political Report rated as D+4.

The result was that neither candidate was in charge of his own campaign—almost everything was shaped by consultants in Washington. That reality underscored a truism of modern campaigns: The more national groups in both parties dominate TV advertising in a House race, the more relentlessly vicious the tone of the 30-second spots. So voters in the district were treated to a barrage of attack ads that began, “Valley workers already know that they can’t trust bad boss John Duarte,” or sneered, “Politician Adam Gray. You pay his salary, but he skips work.” The predictable fruits of this relentless negativism were undermotivated voters on both sides, with California-13 registering some of the lowest turnout in the country for a toss-up race. “This is a pox-on-both-your-houses district,” explained a Washington-based Democratic strategist. “And the Democrats suffered because they were the party in power in Washington and Sacramento.”

The Democrats also suffered because Gavin Newsom’s easy gubernatorial reelection victory radiated all the excitement of watching almonds ripen. In fact, the biggest motivator for Democrats in California was Proposition One, which passed in a two-to-one landslide, enshrining the right to abortion in the state constitution. But the abortion issue did little for Gray in culturally conservative California-13, since Proposition One carried Merced County, which comprises the largest number of voters in the district, by only a 53-to-47-percent margin. Paul Mitchell, who runs a Democratic-leaning California political data analysis firm, stressed, “Josh Harder could have won here.” But that wasn’t where he ran—and the Democrats may be down one seat in Congress because of it.

Losing Margin: 564 votes.

Michigan-10: A Polling Failure

The Democrats may have lost this seat within two hours of a statewide redistricting plan being approved at the end of 2021. Two-term Representative Andy Levin took one look at the map of the new 10th District (which Trump had carried by 1 point in 2020) and decided the safer course was to challenge fellow Democratic incumbent Haley Stevens in a primary in an adjoining district. Levin was wrong: He lost a bruising primary by 20 points. “Andy Levin’s ego and his nerve got in the way,” said Susan Demas, the editor of the Michigan Advance, a nonprofit news site that covers state politics. “Given the Democratic trend line in Michigan, it is difficult for me to conceive of a way that Levin wouldn’t be in Congress right now if he hadn’t changed districts.”

Most of the 10th District is in Macomb County, just north of Detroit, famous as the home of Reagan Democrats, blue-collar union workers who moved sharply to the right in the 1980s. In the twenty-first century, Macomb County has been a weather vane, going for Barack Obama twice and then switching to Trump in 2016 and 2020. This time around, the Republicans got the Trump-endorsed candidate they considered their ideal recruit in the person of 41-year-old Black businessman John James, who had run well in two losing statewide Senate races in 2018 and 2020. Carl Marlinga, the Democratic nominee, was a 75-year-old, former longtime Macomb County prosecutor who freely admitted, with a wistful kind of old-fashioned innocence, “I always wanted to serve in Congress.”

On paper, it wasn’t a fair fight, especially since Marlinga raised only a paltry $1 million, less than one-fifth of what James spent on the campaign. While major Democratic groups stayed out of the race, the GOP-connected Congressional Leadership Fund spent $1.4 million viciously attacking Marlinga over his clients as an attorney in private practice: “Carl Marlinga made his living representing sexual predators.”

All these calculations, however, failed to factor in the potency of the abortion issue in Michigan. Like California, Michigan approved an abortion rights amendment to the state constitution last November. Unlike California, Michigan was a state where abortion could realistically have been in jeopardy. “Marlinga made all the right comments on abortion without the resources to get them out any further,” said Michigan-based Democratic strategist Amy Chapman. “If you asked voters who was the pro-choice candidate, I’m not sure that many voters knew.”

Michigan-10 can fall under the rubric of a polling failure. No one expected Gretchen Whitmer to win reelection by a double-digit margin, including the governor’s own campaign officials, who had the race much tighter. National Democratic groups were certainly willing to play on the Michigan battlefield, since they invested $9 million to prop up incumbent Representative Elissa Slotkin, who won by 20,000 votes in a Lansing-area district. But better polling might have alerted the national party and major donors to the extent of the coming Whitmer sweep in Michigan (the Democrats won both houses of the legislature). With a few more resources, a rising tide would have lifted all boats, including the underfunded Carl Marlinga.

Losing Margin: 1,600 votes.

New York-17: Maloney + Murdoch = Misery

When it came to House races in New York in 2022, the Democrats were as incompetent as Prince Harry and Meghan’s family therapist. Not only did Democratic-appointed state judges throw out a greedily gerrymandered Democratic redistricting plan, but the courts also ruled so late that the House primaries in the new districts had to be moved from June until August. Then moderate Sean Maloney—a five-term House member who was supposed to be protecting the Democratic majority as the head of the DCCC—sized up the new map and jumped to a newly carved Hudson Valley district (the 17th), helping set off a self-destructive game of musical chairs as other incumbents collided in their quest for seemingly safe seats. Maloney’s self-interested decision, for example, forced first-term incumbent Mondaire Jones, who grew up in federally subsidized housing in the district, to run and lose in a House primary in a new district that combined Lower Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn.

When the dust settled, the Democrats lost four seats in the Empire State, almost single-handedly depriving Hakeem Jeffries of a House majority with the returns from his home state. With beleaguered Governor Kathy Hochul, who inherited the job when Andrew Cuomo was forced to resign, at the top of the ticket, Election Day was such a debacle that Republican George Santos—the “Jew-ish” fabulist from Long Island—won his House seat by 20,000 votes in a district that Biden had carried by 8 percentage points.

And we haven’t even gotten to the real reason why Maloney lost his new district.

At the end of 2022, as New York City reported a yearly 13 percent drop in murders and a 17 percent decrease in shootings, the Rupert Murdoch–owned tabloid New York Post buried the encouraging story about the crime rate in half a column on page nine of its print edition. Virtually every other day of the year, especially during the lead-up to the 2022 elections, the Post apocalyptically portrayed New York City as a crime-filled hellscape where residents had a 50-50 chance of surviving each time they crowded onto the subway or grabbed a bagel from a corner cart. The Post is more than just Murdoch’s plaything; it is also the newspaper that still shapes local TV coverage in the vast New York City media market and elsewhere in the state.

“The issue for all Democrats statewide surrounded crime and the ongoing conversation about crime,” said Jef Pollock, who was Maloney’s pollster. “That’s what made New York different from other states. New York state had lowered cash bail—and then had a two-year conversation about that.” When I suggested in an interview that Maloney’s defeat might also be due to other factors, such as a lack of urgency about the abortion issue in a historically liberal state, Pollock snapped, “I think folks are looking for things that aren’t there.”

The Republican soft-on-crime assault, a GOP staple since the days of Richard Nixon, had all the subtlety of a mugging. A typical anti-Maloney TV ad, sponsored by the Congressional Leadership Fund, which put $7.5 million into the race, began, “Violent crime terrorizing New York ...,” and then segued into a 2018 clip of the Democratic incumbent opposing cash bail. The irony is that Maloney deflected a divisive 2022 primary challenge from left-wing state Senator Alessandra Biaggi with the help of nearly $500,000 from a super PAC affiliated with New York City’s police union.

Losing a House district that Biden carried by a 10-point margin required what a Democrat consultant called “a perfect storm,” as Maloney became the first active leader of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee to forfeit his seat in more than four decades.

Losing Margin: 1,820 votes.

Iowa-3: Abortion and Older Voters

Until recently, Iowa was a swing state that went for Obama in both presidential elections and could elect Democrats in half or more of its congressional districts. But thanks to an aging, largely white population with fewer college graduates than the national norm, Iowa became a solidly Trump state in 2016 and has tacked right ever since. After the 2020 election, in which Trump carried Iowa by 8 points, Cindy Axne, representing a Des Moines–centered district, was the only Democrat left in the state’s congressional delegation. For many national Democrats, fixated on fast-emerging states such as Arizona and Georgia, Iowa has withered like a corn husk in winter. “If you live in Washington,” said Des Moines–based Democratic consultant Jeff Link, “you assume that Iowa is a lost cause just like North Dakota and Idaho.” Axne’s narrow defeat last November can be argued both ways—either as the death knell of Democrats in Iowa or as the result of strategic missteps.

Democrats in Iowa normally boast a strong ground game, with lists for door-knocking honed from years of presidential caucuses and practiced methods of harvesting the early vote. But with incumbent GOP Governor Kim Reynolds cruising to a landslide reelection, the Democrats’ statewide effort consisted of little more than campaign posters. The Republican state legislature also tilted the playing field by eliminating nine days of early voting (which traditionally favored the Democrats) and requiring all absentee ballots to arrive by Election Day. The result: Compared to a similar off-year election in 2018, 33,000 fewer early votes were recorded in Polk County (Des Moines), where Axne got the bulk of her support.

Iowa-3 was a district where money didn’t dictate the outcome. The combination of a well-funded Axne campaign ($7.1 million) and comparatively inexpensive Des Moines TV time meant that the Democrats could mobilize a wide array of messages against the GOP nominee, state Senator Zach Nunn. Kyle Kondik, who followed the race for Sabato’s Crystal Ball, noted that one issue dominated Axne’s strategy: “Nunn was pounded on abortion.” At a debate during the GOP primary, Nunn had raised his hand to signify that he opposed abortion in all cases, with no exceptions for rape, incest, or to protect the life of the mother. After the primary, Nunn tried to modify his stance, even writing an op-ed in The Des Moines Register that incorrectly claimed that Axne had “taken out of context comments from a primary debate.” Axne jumped on the flip-flop by running an ad in which a voice-of-doom narrator said, “Recently Zach Nunn took a stand and agreed that all abortions should be illegal. Now Zach Nunn is lying about his extreme position.”

A national Democratic strategist insisted that the Axne tactic worked: “Without that Nunn primary abortion footage, we could have lost by 6 to 8 points.” But Link, who did not work on the Axne campaign, fervently disagrees. “Democrats wanted to focus on abortion because that was working elsewhere,” he said. “But we’re an older state. Axne would have done a lot better highlighting her votes in Congress to cap insulin prices at $35 and limit drug costs for seniors.”

Losing Margin: 2,145 votes.

Arizona-1: National Democratic Fail

A national Republican pollster admitted to me that every two years he is amazed by the political survival of David Schweikert, who has been holding a Phoenix-area House seat since 2011. Arizona Republican activist and former party official Kathy Petsas, who supported less extreme Republican candidates in the midterm primaries, said about Schweikert, “He has nine lives. He’s like a cat. It’s amazing that someone can get out of it with all the baggage he carries around. He shouldn’t have won.”

Begin with two interrelated facts about Schweikert and Arizona-1, a district built around Scottsdale and Paradise Valley to the east of Phoenix: The noncharismatic Schweikert was fined $50,000 for campaign finance violations in 2020 and racked up another $125,000 in penalties in 2022. Also, there were more 2022 campaign ads (mostly for governor and Senate) aired in the Phoenix media market than anywhere else in the country, according to the Wesleyan Media Project, sending airtime costs through the roof.

In another district, the $2.5 million raised by the Democratic nominee, 28-year-old Jevin Hodge, might have been impressive for a first-time Black congressional candidate, who grew up without family wealth. But in the oversaturated Phoenix media market, it was about as effective as putting his campaign message in a bottle and dropping it in one of the lakes in nearby Tonto National Forest. The Democratic nominee could afford to make just a single 30-second TV spot, which was half-devoted to ethics violations and half to Hodge’s earnest pledge, “I’m running to stop D.C. politicians like Dave Schweikert who just look out for themselves.” The House Majority PAC ponied up $1.7 million to run its own version of the attack ad with the key line, “Career politician David Schweikert admitted to 11 ethics violations,” while the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee spent exactly $95 on a toss-up race in a district that Biden carried by 1.5 percent.

Ian Russell, who was Hodge’s media consultant, said ruefully about the failure of national Democrats in this race: “The battle-scarred veterans of previous midterms kept looking at the presidential approval rating and thinking it was impossible.” In truth, these national numbers and this wrongheaded historical extrapolation cost the Democrats a House seat that was nearly in their grasp. “Schweikert was a wounded duck,” said Chuck Coughlin, a Phoenix-based independent campaign consultant who mostly works for Republicans. “Schweikert was capable of losing to the right candidate.”

Losing Margin: 3,195 votes.

New York-22: Losing a Biden +8 District

The most devastating negative ad in this race in an upstate district, which stretches from Syracuse to Utica, targeted the Trump Republican running for the open seat. “Brandon Williams is an out-of-touch phony,” the 30-second spot bluntly began, before pointing out, “Now Williams is running for Congress bankrolled by out-of-state money, living outside the district on his truffle farm.”

Needless to say, the words “truffle farm” were delivered with a sneer.

The most devastating attack line in a debate was levied against Democrat Francis Conole, an Iraq War veteran and former naval intelligence officer from Syracuse. An opponent pointed out that Conole was benefiting from around $500,000 in campaign help from a super PAC largely financed by a cryptocurrency billionaire with the soon-to-be-famous name of Sam Bankman-Fried.

Both of these moments came during the run-up to the August 23 party primaries, which were scheduled nearly two months later than usual because of the redistricting chaos in the state. Williams drew the fire of the Congressional Leadership Fund, the super PAC affiliated with Kevin McCarthy, because he was judged too much of an unabashed right-winger to win in this district. Conole, who had the backing of the national Democratic establishment, was assailed by a major primary challenger for his lack of “personal integrity” in not repudiating the cryptocurrency super PAC help.

Both Williams and Conole prevailed in their primaries. But they secured their nominations too late to do effective fundraising or map out winning campaigns. Williams only raised a paltry $900,000 for the entire race—and was propped up by, yes, the Congressional Leadership Fund ($5.1 million) and the National Republican Congressional Committee ($1.8 million). Conole, who raised $3 million overall, was strongly backed with another $4.3 million of national Democratic spending on his behalf. Part of the reason for the Democrats’ heavy commitment was the competitive nature of the district, which Biden had carried by 7.5 points, and part was that, in the words of a Democratic insider, “You couldn’t write a better biography for an upstate New York Democrat than Conole’s.” By the way, Bankman-Fried, who soon developed preoccupations other than politics, spent no further money in support of Conole in the general election.

In his TV ads, Conole played the extremist card against Williams, charging in an emblematic commercial, “He’s a radical Republican who would let politicians outlaw abortion even for victims of rape.” A negative spot from the Congressional Leadership Fund linked Conole with a woman whom the GOP viewed as even more unpopular with swing voters than Nancy Pelosi: “If you like Kathy Hochul, you’ll love Francis Conole. Albany’s bail reform is fueling crime.”

Even though New York’s 22nd District is far from the New York Post’s circulation area, the crime issue still had powerful reverberations upstate. Luke Perry, a political scientist at Utica University, explained, “It wasn’t like voters in suburban Oneida County or Syracuse worried about crime themselves. But it connected to other issues like immigration and opioids that did concern them.” In the end, Hochul’s political baggage was too much for Conole to lift, even though he ran about 6 points ahead of the governor in the district, according to one Democratic consultant’s calculations. A top Democrat in Washington summed up this losing race in a fatalistic tone reminiscent of the movie line, “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown.” In this case, the Democratic operative said with a sigh, “New York is really tough in midterms.”

Losing Margin: 2,631 votes.

Nebraska-2: An Instinct for the Capillaries

Don Bacon, who first won this Omaha-centered seat in 2016, is the rare Republican incumbent who still gets away politically with portraying himself as a moderate. Bacon, for example, was one of just 13 House Republicans who voted in 2021 for Biden’s infrastructure bill. Partly reflecting this diverse-for-Nebraska district (11.6 percent Hispanic), Bacon, as a backer of DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, has been largely supportive of efforts to protect the “Dreamers” from being deported. “Don Bacon is very good at taking issues off the table,” conceded a Democratic consultant familiar with the race. “The one area where Bacon’s mask slipped was with his unwavering zeal for abortion restrictions.” Democratic opposition research found a 2016 right-to-life questionnaire in which Bacon had ticked the boxes indicating that he opposed abortions in any circumstance, including in cases of rape and incest.

After the Dobbs decision, the Democrats seemingly had a winning issue in a district that Biden had carried by 6 points in 2020. There was only one problem: The Democratic nominee, Tony Vargas, a state senator who supports abortion rights, had an instinct for the capillaries rather than the jugular. Vargas, who raised $3.4 million, preferred to run positive ads and refrained from launching a major attack on Bacon until late in the campaign. A typical Vargas spot was built around the story of his now-healthy daughter, Ava, being born prematurely. “We were lucky,” Vargas said in the ad. “But access to care shouldn’t be about luck. So, as state senator, I fought to expand affordable care for thousands of Nebraskans.” That would have been a fine commercial if Vargas had been running for reelection to unicameral legislature rather than trying to knock off a difficult-to-dislodge Republican incumbent.

Even the national Democratic groups, despite their single-minded emphasis on abortion in other districts, employed a scattershot approach to going after Bacon. For example, in late September a DCCC ad predictably attacked Bacon for “voting to threaten Social Security and to gut Medicare.” The House Majority PAC hit Bacon as a mouthpiece for special interests in a commercial that began with a weak jibe about the GOP incumbent’s name: “Washington politicians like Mitch McConnell live high on the hog. And Don Bacon is no different.”

In hindsight, some Democratic insiders admit, “This was a winnable race.” Except the Democratic nominee didn’t bring home the bacon.

Losing Margin: 5,856 votes.