In Raoul Peck’s documentary I Am Not Your Negro, writer James Baldwin observes, “History is not the past. History is the present. We carry our history with us. To think otherwise is criminal.” Baldwin’s remarks succinctly capture our relationship to the past. They also address the role of “presentism”—the use of a present lens to interpret the past—within the historical profession.

Historians often use the term “presentism” as a critique—to cast doubt on the objectivity of scholarship from those who consider the present in their analyses of the past. Scholars who resist “presentism” will argue that it somehow distorts the historical narrative. According to this thinking, one should never consider present circumstances when interpreting developments of the past—or when trying to understand figures from the past. To do so is to defy the very essence of the profession, one supposedly based on neutrality.

James H. Sweet, president of the American Historical Association, certainly seems to think so. In an essay titled “Is History History?” in the September issue of Perspectives, the AHA’s monthly magazine, he bemoaned a “trend toward presentism” in historical analysis, rhetorically asking, “If we don’t read the past through the prism of contemporary social justice issues—race, gender, sexuality, nationalism, capitalism—are we doing history that matters?” He later added, “If history is only those stories from the past that confirm current political positions, all manner of political hacks can claim historical expertise. Too many Americans have become accustomed to the idea of history as an evidentiary grab bag to articulate their political positions.”

Sweet’s critique ignited a broad debate about the role of the present in historical analyses. The backlash prompted Sweet to append an apology to his essay, which some on the right saw as caving to the “woke mob.” But as a Black historian who understands the power of my writing and research, there is little to debate. Black historians have long recognized the role of the present in shaping our narratives of the past. We have never had the luxury of writing about the past as though it were divorced from present concerns. The persistence of racism, white supremacy, and racial inequality everywhere in American society makes it impossible to do so.

Historians, like anyone else, exist in the present, and our work will always reflect contemporary realities—explicitly or implicitly. Contrary to popular belief, there is no standard or “neutral” interpretation of the past. The typical standard historical account of the United States, for example, is often distorted into narratives that deemphasize the contributions of people of color and uphold racial stereotypes. This was intentional. Consider the work of historian Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, widely recognized in his lifetime as one of the most influential historians of the South. His 1918 book, American Negro Slavery, was widely read and cited. Yet it offered no “objective” historical analysis. To the contrary, the book only served to perpetuate racist stereotypes about African Americans, and it helped to reinforce segregation and exclusionary laws in the U.S.

Black historians worked to challenge these kinds of accounts during the 1920s. Anna Julia Cooper’s 1924 dissertation in the field of history at the Sorbonne University in Paris directly condemned the institution of slavery. As European nations maintained colonial rule, exploiting millions of people of color across the globe, Cooper wielded her scholarship as a weapon to challenge the global color line.

Carter G. Woodson, founder of Black History Month and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, responded similarly. By establishing “Negro History Week” in February 1926—which would later become Black History Month—Woodson disrupted educational norms in the U.S. shaped by white supremacy and anti-Blackness. “The so-called modern education, with all its defects,” he explained in his provocative 1933 book The Miseducation of the Negro, “does others so much more good than it does the Negro, because it has been worked out in conformity to the needs of those who have enslaved and oppressed weaker peoples.” Societal change is impossible, Woodson argued, when we fail to interrogate the standard accounts of history and other fields of study. Telling “neutral” historical accounts of egregious practices such as slavery and lynching serves a fundamental purpose—to excuse injustices of the present and thereby maintain systems of oppression. It is a form of purposeful amnesia designed to empower oppressors.

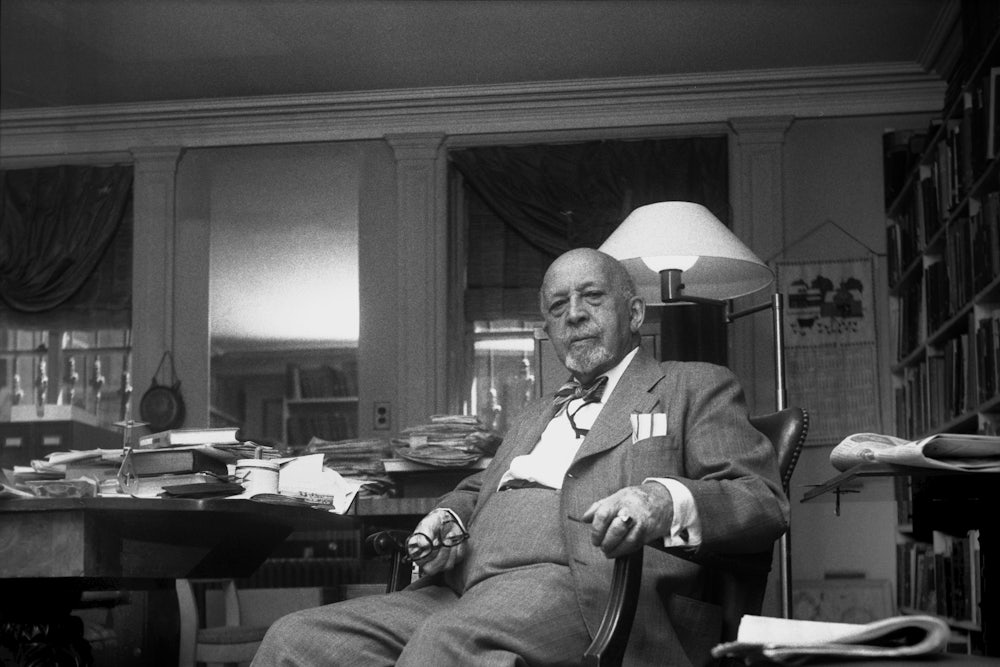

Historian W.E.B. Du Bois also made this observation in his 1935 magnum opus, Black Reconstruction in America. His final chapter, “The Propaganda of History,” confronted the many lies that “objective” historians were peddling at the time about the history of Reconstruction. His pioneering book, published against the backdrop of a surge of Black radical movements of the Great Depression, directly refuted the false narratives emerging from leading white scholars of the Dunning School (named after William Archibald Dunning of Columbia University). In their portrayal of Reconstruction, the Dunning School scholars, as Du Bois explained, had portrayed the South as victims and the North as having committed a “grievous wrong.” Their writings on the subject treated the free and enslaved Black population with “ridicule, contempt or silence.” They also peddled racial stereotypes and mischaracterizations of Black intellectual ability.

The Dunning School’s interpretation of the past was very much shaped by present concerns at the time. They used their writings on the past to justify—and give moral validity to—the mistreatment of African Americans. The scholarship of these historians served to reinforce segregation and racial discrimination in the U.S. during the early twentieth century. White policymakers, educators, and others cited the racist interpretations of the Dunning School to further limit Black access in the public sphere and to uphold stereotypes. The same scholars decrying “presentism” today most likely would have framed Du Bois’s powerful rebuttal in the same manner—as some of his critics did. But were it not for scholars like Du Bois, we would still be relying on the white establishment’s racist accounts of Reconstruction.

Du Bois’s response to the Dunning School, as well as the efforts of Anna Julia Cooper and Carter G. Woodson, exemplify how Black historians have taken an active role in confronting political abuses of the past. They were not alone. Marion Thompson Wright, Dorothy Porter Wesley, and Merze Tate were among the first generation of professional Black historians who used their writing and research of the past to address myriad contemporary social issues. They recognized, as Manning Marable, the founding director of the Institute for Research in African-American Studies at Columbia University, observed in 1998, that “scholarship and social struggle cannot be separated.”

Indeed, historians do not produce scholarship in isolation. The work we do has the potential to shape national debates and inform policies that have broad implications for all Americans. The weight of this responsibility is especially great for members of marginalized groups. In a white-dominated world and academy, we are always fighting to assert our voices and our histories into spaces designed to exclude us.

More importantly, we are fighting for our lives. The commitment to engaging present concerns is not simply a method or approach to the scholar’s craft of research and writing. It is a matter of life and death. The reality of the present moment propels many of us to act. In the spirit of Du Bois, Woodson, Cooper, and others, we have a duty to lend our expertise to the most pressing issues of our day. It is not only logical and responsible to do so; it fulfills the underlying mission of historical study in communities of color to illuminate the complexity of our lived experiences.