Five months pregnant, Diana Apresa and her husband Michael Romo were in a difficult spot, forced to make a decision that would reduce their annual income by more than a third. Diana needed to quit working for the small handyman business they owned in Phoenix, Arizona to lessen her physical stress. “Being a pregnant woman fixing stuff and moving ladders is not ideal,” she said.

Instead, Apresa searched for a remote part-time job, and day care for their newborn. But the price of day care—even just part-time—was as high as $1,200 a month, equaling about the same amount the couple estimated Apresa would earn to fill their income gap. At the same time, landing a job while pregnant quickly evolved into another hurdle, despite a decades-old law that technically prohibits pregnancy discrimination in employment. “Nobody wants to hire you,” said Apresa, 35, who decided to put her job search on hold. “It wasn’t worth going through it all.”

The couple cut their household expenses to sustain their family, and Apresa gave birth to their son, Isaac, in September. Nearly 10 months later, she finally landed a part-time gig. “We need the money.… It definitely has been challenging, [but] we’ve made it work,” she said.

Apresa and Romo are among the more than 12 million working parents with kids younger than six—a segment of the population that contends with a unique, economic double bind: without an option for paid leave, parents must find childcare in order to work and provide for their families (right after covering the exorbitant health costs for giving birth). But skyrocketing childcare costs often mean there’s nothing left over anyway. And the government—both at the state and federal level—has often left these families behind without any comprehensive solution for this unique stage of life.

The downstream consequences of this policy failure to support families are impossible to overstate. Early childhood is a critical time—children’s brains are forming more than a million neural connections per second as they approach three years old. Research has shown how poverty and low incomes can have a significant, negative long-term impact on a child’s wellbeing, while a recent study for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that monthly cash payments to mothers during the first year of their children’s lives led to faster brain activity, “a pattern [positively] associated with learning and development at later ages.” The impacts also matter for society at large. The earliest years of a child’s life are hugely consequential. Care and family income are critical drivers here. Yet these earliest years from zero to five—the years that arguably ought to draw the most robust policy response—are also the most vulnerable, and served by piecemeal policy interventions that are not fully funded.

It’s time for a new approach to support families.

Today, U.S. spending on early childhood education and childcare as a percent of GDP is among the lowest in OECD countries. It is one of only two that does not cover health care costs, and we are the only high-wealth country without any type of guaranteed paid leave.

During the early and middle part of the twentieth century, the United States realized that seniors were a group of people uniquely vulnerable to economic dislocation, who needed specialized support programs to ensure their economic security. Beginning on a small scale with the Civil War Pension program, and then starting in earnest with the creation of Social Security during the Great Depression, and expanded later through other programs such as Medicare, the federal government has built a full apparatus focused on helping this cohort. Today, the elderly have the lowest poverty rate thanks to comprehensive health care and cash assistance.

It’s time to bring the same focused, and far more robust, approach to families with young children. A paradigm shift towards a comprehensive policy agenda that sees families with young children as a distinct group with unique needs grounded in access to care supports—one that we as a society share a collective responsibility to meet—is necessary to ensure the health of families and the economy.

Such policies would be an investment in the stability of families at a critical time. They would also be preventive investments, recouped many times over by supporting trajectories of health and wellbeing for children and reducing public costs and institutional involvement over their lifetimes.

The High Cost of the First Five Years

The unique vulnerability of the lowest income families with the youngest children stems from the confluence of reduced income at precisely the moment when expenses rise for most families and a lack of care infrastructure that could support families in this time.

In 2019, nearly one in six children younger than age six lived in families below the poverty line ($27,750 for a family of four), and almost 71 percent of all children living in poverty were children of color. Children are three times more likely to live in poverty than seniors.

For many families, the costs associated with having and raising young children can lead to economic precarity. For example, the average two-parent household sees an income drop of $14,850 when they have children, accounting for 14 percent of total earnings, according to an analysis by Demos. It’s even tougher for a single adult, especially for women, who may see a 36 percent drop in earnings. It should hardly come as a surprise that, in recent years, parents have been having fewer children than they say they want, and that many have cited the cost of childcare as a major reason why. In the absence of federal policies supporting paid leave or subsidized childcare options, this income gap can become a chasm; it can thrust families into poverty.

Not only do families lose income during the first five years of their children’s lives, but they also incur additional expenses. After spending thousands out of pocket to pay for delivery of a child, the average nationwide price for a center-based childcare provider and preschool is about $1,230 per month for an infant, according to analysis from World Population Review, with center-based childcare for toddlers clocking in at $904 per month. Annually, that cost for an infant adds up to be more expensive than public college tuition in 28 states and the District of Columbia in 2019.

But that’s just the extra expenses of having someone watch your child while you’re at work. There’s also a myriad of other new purchases when an infant enters the home: baby food, formula, and diapers, which in total can cost a family nearly $2,500 a year (or $50 a week). This was before the country faced a massive formula shortage earlier this year, one which has improved but is still adding extra burdens. The costs of having young children are hardly sustainable for minimum wage workers, who, if they don’t live in a state that sets a higher rate than the federal government, earn only $1,256 per month when working 40 hours per week.

And then there is the time off parents need to recover from birth. Only 23 percent of workers have access to paid leave. Meanwhile, less than 50 percent of workers have access to two months of expenses. This means families simply cannot afford to take time. Access to a federal paid leave program would have given Apresa and Romo a chance to breathe during Apresa’s 10 months out of work, particularly during the beginning, by helping them stay ahead of monthly bills like rent and food. “In the end, I would’ve still had to get a part-time job,” she said. But “it would’ve helped.”

Karla Torres, a 34-year-old single mother of three living in Phoenix, knew paid leave would have lessened the stress of having to return to work six weeks after giving birth to her youngest, who just turned five years old. At the time she was pregnant, Torres worked as a shift-manager at a local fast food restaurant, where she had been for 12 years. Her shift was during the evenings. “I remember that I really rushed myself to get better and to go back to work, because it became such a hard time to just maintain our house and our bills,” said Torres, adding that her mother had come to help her through the transition. “Paid leave would’ve made a huge difference,” she added.

Faced with these impossible choices, parents do what they can. Torres pays $800 a month out of pocket to a neighbor for day care, because she didn’t qualify for childcare assistance due to her income. “That’s a lot of money for us but I have no options,” she said.

Out of concern for the cost and potential long wait, Clarissa Villebrun, a single mother of two from White Earth Nation in Ogema, Minnesota, submitted an application to local day care centers upon learning she was pregnant with her youngest son. That included applying for childcare assistance since Minnesota ranks as the fourth most expensive state for such care. There was cause for that concern, considering all of the nearby childcare centers on the reservation had a waitlist. (Her oldest daughter, who is now 10 years old, turned three before a spot became available.)

Being proactive worked in Villebrun’s favor, but it was a challenge to navigate through the system itself, she said, adding that she needs to maintain that subsidy, which covers a monthly $400 co-payment, in order to stay afloat. “If I didn’t have day care—and childcare assistance—for [my son], I don’t think I’d have a job,” said Villebrun, 29.

Of the 12.8 million children who were eligible for childcare subsidies in an average month in 2018, only 15 percent actually received assistance. Childcare subsidy programs are woefully underfunded and do not have the resources to assist everyone who is eligible. Finding an available spot in a childcare center also has become a real struggle. The lack of funding for childcare over the decades has created deserts of high-quality, affordable day care and preschool options for parents in virtually every state. The strain was only exacerbated during the Covid-19 pandemic. Day cares closed or lost workers; those that remained open have waiting lists that are up to a year, while costs continue to increase.

“Working my way up as a single parent, I feel that’s been the most challenging part,” Villebrun added.

A Temporary Lifeline

It is no accident that the United States lacks a host of essential policies that would support low-income families with young children. America has a deep antipathy to polices perceived to benefit non-white families, particularly non-white women, and racist narratives of deservingness have been used to limit access to benefits and support since the earliest days of the country. Systemic racism, built into our policies, hurts all Americans. There is a clear through line from the exclusion of care workers from the New Deal to the lack of investment today: Neither care nor those providing it is valued.

As Darrick Hamilton, a professor at the New School explains, “From childcare to paid leave to meaningful cash assistance, the system of care and care workers has been degraded. We have a long history of relegating Black and Brown people in particular to ‘essential’ jobs that are devalued in pay and work conditions, which goes a long way in explaining why we don’t have policies that value care, and as a result we all suffer.”

Today, millions of families must navigate not only the most current and universal challenges, such as the unprecedented onset of Covid, but also the compounding impact of hundreds of years of systematic efforts to deny them the resources to thrive. “These families need a lifeline,” said Lori Gunnink, Head Start director at the Southwestern Minnesota Opportunity Council (SMOC) in Worthington, Minnesota. In SMOC’s early childhood education program, Gunnink closely works with various communities of color, who are most vulnerable when it comes to the many hurdles parents have to overcome when caring for small children. “It takes a village to raise a child—that always has been true, but even more so, we need to recognize how stressed and stretched these families are.”

As part of the American Rescue Plan signed into law last year, Congress provided a lifeline to these families with young children by providing $39 billion dollars in emergency childcare assistance and dramatically expanding the existing child tax credit and disbursing it in monthly payments, a move that reduced child poverty by a third—keeping 3.7 million children out of poverty. But the child tax credit expansion expired at the beginning of the year and the childcare measures were largely temporary infusions to states and providers.

At a time when the press is full of stories describing a shortage of workers, labor force data show that mothers with young children such as Villebrun are less likely to be in the workforce than mothers of older children. A recent survey of families with kids under five found that almost 40 percent of female caregivers left the workforce or reduced their work hours since the pandemic began, largely because of childcare related challenges. They might want to return, but they have little support to do so. A recent study issued by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that an expansion in childcare subsidies would boost employment among moms of kids ages 3 to 5 up to 78 percent—a full 10 percentage points above the current level. And according to the Economic Policy Institute, labor market participation among women would potentially add more than $210 billion annually to the economy if there was meaningful investment made in affordable childcare. Not only is the lack of investment in care harming families, but it is hampering our economy.

Time for a New Paradigm

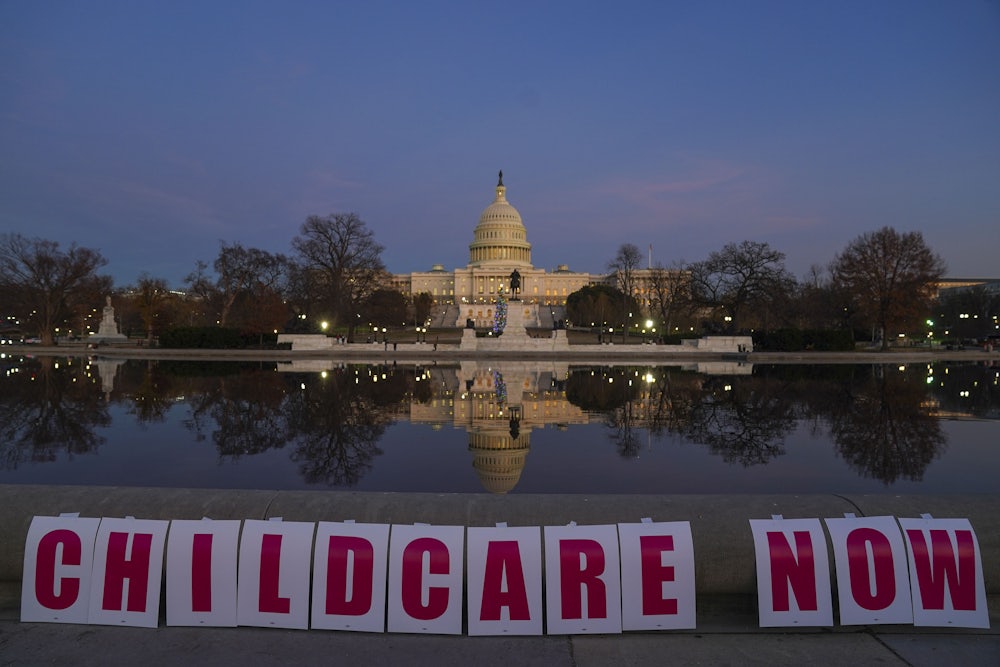

Over the weekend, the Senate passed a long-delayed reconciliation bill that tackles a host of domestic policy issues, from fixing the tax code to transformational investments in green energy. The bill came about after Senators Joe Manchin and Charles Schumer announced that they’d reached a compromise for a scaled back version of President Joe Biden’s original Build Back Better plan. While climate and health care made the revised package, now dubbed the “Inflation Reduction Act,” which is expected to be voted on by the House later this week, millions of dollars to support families with young children did not make the final cut. Paid family and medical leave, childcare, universal Pre-K, and an extension of long-term care dollars that states used to augment care worker wages during the Covid care crisis all lost their spots in the final bill.

“Every policy aimed at women and family and care infrastructure disappeared,’ said Ai-jen Poo, who heads the National Domestic Workers Alliance. “Every single one.”

Schumer explained the omissions as a necessary concession in order to get any of the original Build Back Better priorities over the line, and that may be so. Yet, by leaving investments in every care policy out of the proposal, the Inflation Reduction Act has ignored the brutal and fundamental relationship between the spiraling costs of care and the overall cost of living for families with young children.

Where, then, can policy makers go from here?

One near-term pathway may be for relevant states to create or improve their paid leave policies by expanding payouts, as 11 states and the District of Columbia have done in recent years, or by improving access and user experience for eligible families, as New Jersey did by trying to smooth the experience of those accessing maternity leave. Still, the number of Americans covered by state paid leave programs is small. At the federal level, in June, a group of Republicans led by Senator Mitt Romney rolled out a limited, insufficient proposal to provide child-based income support for families, demonstrating at least some bipartisan recognition that families need help.

However, while states can help on the margins, and some limited federal laws could get passed, what is actually needed is a new paradigm, one that centers these families as a distinct class of people the same way the federal government treats seniors. Even if states choose to act, or if something like the Romney plan was to become law, the fundamental reality of family economic policy in the United States—namely that it is thin, incidental, and piecemeal—will not change.

Smoothing the path to stability for the lowest-income families in America, and safeguarding a thriving future for their children, requires a comprehensive approach that both values care and treats families with young children as a unique segment with interlocking economic needs. It also requires us to truly value care: both the labor of caring for children, and the people providing that care, while broadening the idea to normalize paternal leave and compensate for unpaid care in the home. Investing comprehensively in our national care infrastructure would allow families to access childcare, paid leave, emergency cash, and other proven, pro-family supports when their children are young, helping families today while ensuring the long-term health of their children and our economy as a whole.

“If there was a lesson to be learned during the pandemic,” said Poo, “it’s that the lives of working parents with young children, especially mothers, and care workers, and the fate of the economy rise or fall together.”