Americans caring for their loved ones are experiencing a confluence of crises. There’s an ongoing pandemic that has seen millions of people leave their jobs, disproportionately affecting women who take on caregiving roles. Millions of people are quitting, in a phenomenon known as the “Great Resignation,” and companies are struggling to hire new employees. Worker frustration has culminated in “Striketober,” with many low-wage employees calling for better pay and benefits. It also comes amid a crisis in home health care and in childcare, exacerbated by low wages.

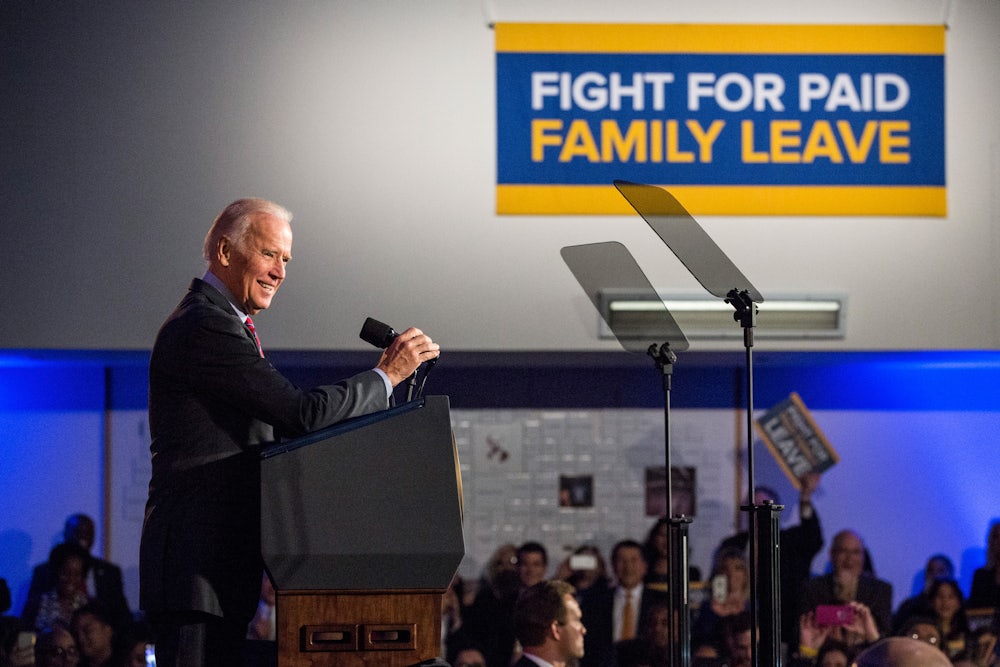

Meanwhile, in Washington, Democrats are currently attempting to negotiate and single-handedly pass a massive social spending bill that might address some of these issues. One of the key provisions in the bill’s original conception was a paid family and medical leave proposal, which would offer 12 weeks for taking care of a new child, recovering from a serious illness, or caring for a seriously ill loved one. Paid leave is enormously popular across party lines: A September poll by CBS News found that 73 percent of Americans support a provision providing paid family and medical leave.

But Senator Joe Manchin has reportedly expressed opposition to such a long period, leading the White House to float a proposal to reduce the duration of the benefit to a mere four weeks. Manchin has also insisted that he is unwilling to support a bill costing more than $1.5 trillion, leading Democrats to search frantically for methods of slimming the package down. (There are also disagreements as to how the bill, including any paid leave provision, will be paid for, but that’s a problem for a different article.)

“It is down to four weeks. And the reason it’s down to four weeks is, I can’t get 12 weeks,” President Joe Biden said about paid leave in a CNN town hall last week. Speaker Nancy Pelosi said in an interview with CNN on Sunday that four weeks of paid leave is “what we’re fighting for.” Moreover, if four weeks of paid leave is included in the final bill, it may only be implemented for a temporary period, as Democrats mull shortening the time frame for programs so that they can cram more into the bill. But it remains a possibility that paid leave could be cut entirely—a move that supporters warn could leave Americans struggling with both economic and medical hardships without any support at all.

“Paid leave is literally the one piece of this package that could touch any household in America, at any of the most happy or scary times in their lives,” said Vicki Shabo, senior fellow for paid leave policy and strategy at New America’s Better Life Lab. “The fact that it’s comprehensive means that it is usable by people across life circumstances, age, family types. It recognizes that giving and receiving care is a basic need, and it’s a uniting policy in a way that so few are these days.”

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, who has been negotiating with Manchin on paid leave, told reporters on Tuesday that she was working on a new proposal with Manchin to address the issue, within the reconciliation bill. “I don’t want to upset the applecart. I’d like to try to get my colleague to a place where he’s comfortable, and I’m hopeful that this new idea could be positive,” Gillibrand said.

Senator Tim Kaine cautioned to reporters on Tuesday that “there’s nothing guaranteed about this thing until you and I see a final passage,” and that there was “a range of opinions on paid leave.”

“We’ve done 12 weeks of paid parental leave for federal employees, we did 12 weeks of paid parental leave for our military, there isn’t any reason we can’t do it for working people,” Kaine said, referring to the provision in the National Defense Authorization Act this year expanding paid parental leave for all servicemembers.

The initial proposal by congressional Democrats differs from other paid leave programs around the world with its expansive definition of caregiving and family. It would include care not just for infant children or elderly parents but also for in-laws, domestic partners, grandparents and grandchildren, and loved ones who “by blood or affinity” are considered the “equivalent” of family. The version of the proposal considered by House Democrats would go into effect in 2023 and would replace wages on a scaled basis, depending on income.

“The most important reason for doing this right now is that it really is an economic recovery strategy. Paid leave is a job retention strategy. It’s an economic stability strategy. And it’s a pandemic response strategy,” said Hannah Matthews, deputy executive director for policy at the Center for Law and Social Policy.

The United States is not only lagging behind other wealthy countries in its lack of a national paid leave program but is an outlier in the world as a whole. As The New York Times reported this week, it is one of eight countries without a national paid maternity leave, one of 11 countries that does not offer paid leave for health programs, and one of 85 that does not provide paid paternity leave. Even if Congress did successfully pass a program offering some period of paid leave, either at four or 12 weeks, the U.S. would still fall short of the kind of leave provided by most other countries. The average length of time for paid maternity leave across the world is 29 weeks, and the average length for paternity leave is 16 weeks, according to the World Policy Analysis Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Most countries that provide paid health leave offer it for months, and dozens offer it for a year or more if needed.

Most workers in the country are not currently covered by a paid leave policy. The Family Medical and Leave Act, passed in 1993, guarantees up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for certain employees. Around 56 percent of the American workforce is eligible for FMLA leave, because the program only applies to people who work a certain number of hours, for companies of a certain size. Only nine states and the District of Columbia have paid leave requirements. Some companies voluntarily offer paid leave, but there is no universal system for all workers. Just 23 percent of private industry workers had access to paid family leave in March.

A national paid leave program could alleviate some of the work-related anxieties to which Americans commonly attest. “We learned in the pandemic that life happens. The unexpected happens to all of us. And it’s not good for the economy when people are forced to choose between caring for themselves or their families and their jobs,” said Dawn Huckelbridge, the president of Paid Leave for All, a group advocating for a national paid leave program.

A September poll by Morning Consult and the Bipartisan Policy Center found that more than one-third of unemployed adults said they would be more likely to return to work sooner if their employer offered paid family leave. More than half of respondents who had reduced work hours during the pandemic said they would be more likely to increase their hours if they had paid family leave.

“It would be transformative to be able to not have to make the choice to go to work or miss those early days with a newborn. It would be transformative to be able to sit at the bedside of a dying parent without worrying about risking your family’s financial security,” Matthews said. “The care needs for families are universal: Every family will experience it at some point, every worker will experience it.”

There’s a solid body of evidence that suggests paid leave has a positive effect on parents and doesn’t adversely affect employers. Paid maternity leave is associated with improved physical and mental health for both mothers and infants, and improves early life outcomes for children, which can lead to later economic growth. A 2019 study focused on Sweden found that paternal leave improves maternal mental health, as well, and reduces risk of physical postpartum health complications for mothers.

Advocates of paid family leave also argue that it would increase gender equity in the workforce. Women are often the primary caregivers in their households, for children and other relatives. Research has shown that paid leave can help women remain in the workforce after the birth of a child. One study found that California’s paid leave program reduced risk of poverty among mothers of infants and increased household income. Supporters of paid leave also argue that leave is good for businesses, as it reduces costs of turnover that come with workers leaving their jobs, increases productivity, and allows small businesses to compete with larger companies. An October study of New York’s paid leave program found no evidence of “adverse impacts on employer ratings of employee performance.”

There’s also benefit from redefining paid leave to be more inclusive, not just for new parents but for people at any stage of their lives. “It changes the perception of what the policy is, and puts us all in it together, and really makes it more like an insurance system, rather than a benefit that only applies to certain people who choose to have children at a certain time,” said Maya Rossin-Slater, associate professor in the Department of Health Policy at Stanford University School of Medicine, and an expert on paid leave.

Paid leave can also address racial disparities in the workforce. Black, Asian, and Hispanic Americans are more likely to live in multigenerational households than white Americans and therefore may be more likely to have responsibilities for eldercare. Black and nonwhite Hispanic workers are disproportionately represented in low-income jobs, which are less likely to have paid leave programs. An October report by the National Partnership for Women and Families found that Latina and Black women would see higher earnings replacement from paid leave than any other group.

But Rossin-Slater noted that many of the studies showing the benefits of paid leave are for programs applied for a period longer than four weeks. For example, a leave time of 12 weeks is associated with lower preventable hospitalizations for children, because parents are able to stay home with their children instead of perhaps putting them into a group childcare program at a young age. However, if the paid leave is only for four weeks, children may go into a group childcare setting at a younger age, when they are more susceptible to certain illnesses.

This feeds into concerns over implementing a policy of four weeks’ paid leave for just a temporary period, after which lawmakers could choose to allow the program to expire instead of renewing it.

“It’s better than nothing, but ... if you have a four-week paid family leave policy, we’re not going to just see dramatic, positive impacts from a policy like that. It’s just too small to have huge impacts,” Rossin-Slater said. “If its continuation is being evaluated based on whether we see big positive impacts as a result of this temporary policy, my concern is that we’re probably just not going to see that much. And then we’re back to square one, because then people might argue, ‘Well, we tried it, it didn’t really have much of an effect.’”

Experts agree that having a paid program in effect, even for a temporary period of time, and even if it is not for as long as initially hoped, is better than no paid leave at all. “To the millions and majority of Americans right now who don’t have a single day of guaranteed paid leave, four weeks is certainly still meaningful,” Huckelbridge said.

Setting up the infrastructure for a national paid leave program may also be an important first step in ensuring its permanence. “Although a permanent program is the preferred approach, having a program established, set up, running, providing benefits to workers is a crucial first step. I am confident that paid leave is so popular and in demand in this country that there will be every reason to renew a program and ensure its continuity in the future,” Matthews said.

The main priority for advocates now is ensuring that paid leave is included in any form.

“I think it is inconceivable and incomprehensible,” Shabo said. “That we are at risk of potentially coming through a pandemic, coming through a labor shortage, coming through a historic period of women needing to leave jobs, facing more constricted ability for family members to care for loved ones as the population ages and had a year of historically low birth rates—all of which paid leave addresses—and that we could come through this reconciliation bill process without anything to address paid leave is shameful and would be a national tragedy.”