One of culture’s biggest lies is that great poets and artists are somehow more interesting than the rest of us—deserving to be scanned, emulated, interpreted, explained, and packed up in big valise-size biographies with the usual accessories: indexes, bibliographies, chronologies of where they went and what they ate, and directions to the nearest library-sponsored, well-humidified collections of their tattered letters and scribbly notepads. In fact, it’s often hard to read a prominent poet or enjoy a properly curated assemblage of their works without climbing through several decades of analysis, failed marriages, and/or psychological breakdowns—an empire of words established by people who make it difficult for us to enjoy poetry or art without their help.

And yet the most profound aspect of Frank O’Hara’s poems, and the personality that shaped them, is how deeply and immediately they have spoken to their audiences over the decades, without any need for interlocutors. His intelligent, loosely formal, sometimes chaotic poems often bear unpretentious titles, such as simply “Poem,” or a phrase that announces the occasion or location for which they were written (“Seventh Street,” “The Day Lady Died”). O’Hara referred to many of these as his “went there and did that poems”—peripatetic exercises in observation, reflection, and random urban experience that can only be enjoyed in big cities like New York, London, or Paris.

O’Hara didn’t wear his identity as a poet guru on his sleeve; rather poetry was more like something he did on his lunch breaks and in the interstices of his hectic social schedule of partying, chatting with friends, energetically exploring the Manhattan streets he loved, and engulfing himself in numerous intense friendships and sexual relationships. He worked full-time at the Museum of Modern Art, eventually curating shows by many friends who would become known as the abstract expressionists, such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Robert Rauschenberg, with whom he boozed and sometimes battled at the Cedar Lounge. When he died prematurely in an auto accident on Fire Island in 1966, he was primarily known as a museum curator, and his New York Times obituary was subheaded: “Exhibitions Aide at Modern Art Dies—Also a Poet.”

O’Hara’s long-lasting affections for others seemed to be healthily reciprocated, even many decades after his death. One of his most enduring friends (and sometime lover), the artist Larry Rivers, recalled in Brad Gooch’s biography of O’Hara that there were “at least sixty people in New York who thought Frank O’Hara was their best friend.” Much like his love of everything readily available in 1950s Manhattan—art, museums, music, opera, classical orchestras, and jazz music—O’Hara’s affection for the world was boundless. And he went on to establish boundless social horizons wherever he went.

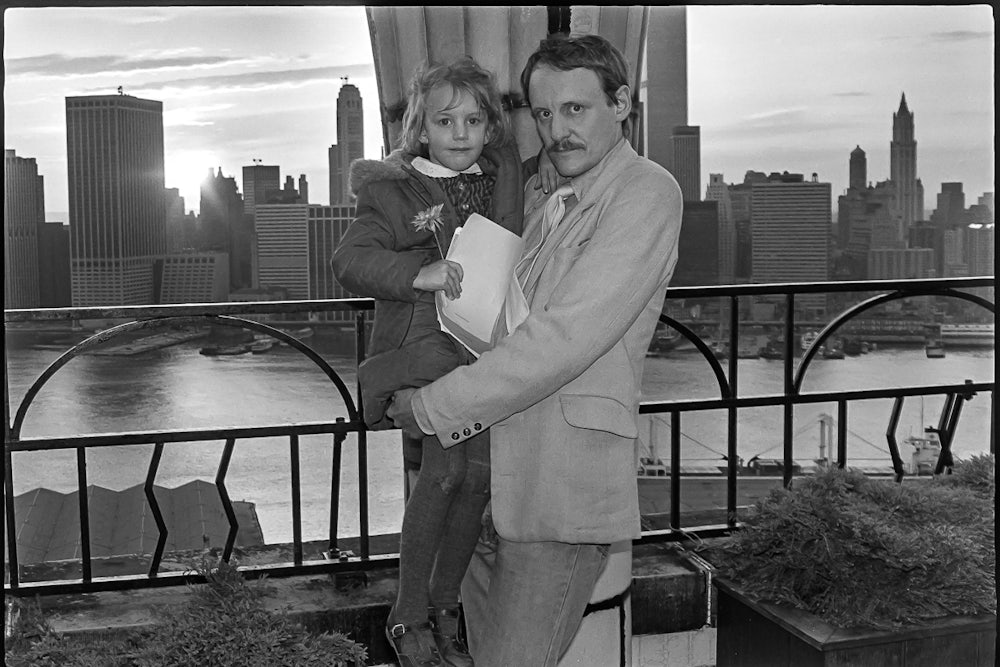

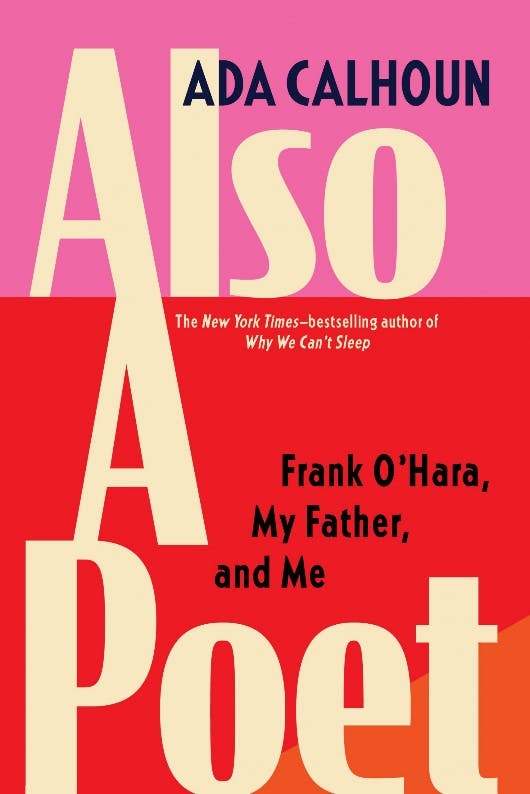

One of the fellow New Yorkers who was revivified by O’Hara’s language-enriched life was Ada Calhoun’s father, the New Yorker art critic (and “also a poet”) Peter Schjeldahl. In the 1960s, soon after O’Hara’s death, he began gathering materials and taped interviews for a biography of a poet he described as having possessed “that most dubious and enchanting of gifts, the ability to romanticize reality, for oneself and others, as it is happening.” And from a young age, Ada Calhoun shared her father’s affection for O’Hara. “There was something about his poems that made me feel like I was sharing a wonderful secret,” she writes in her new book, Also a Poet. “A verse about how a drink tasted or a city block looked felt like an invitation to another world.”

Calhoun’s book grew from an impulse to pick up her father’s abandoned O’Hara project and carry it to the finish line. Part biography, part memoir, it reflects the half-spoken belief that writing about the things and people we love is often a lot easier than living with them.

What drew father and daughter to O’Hara was his immediacy—an unpretentious playfulness, which Schjeldahl probably summarized best in a brief article explaining modern art to teenagers: “As at the beach, a splash can be a very beautiful thing.” Like the abstract expressionists he admired, O’Hara didn’t produce objective, scannable art for educated observers; he only wanted to splash around in the daily experiences of life, transforming them into public displays of affection for the city and people he loved. He wrote a huge (possibly too huge) volume of work very quickly, with apparently no literary self-consciousness or self-doubt; and since he died young, he never got pulled into the late-life work of explaining his work to others or having to listen while others explained his work to him.

His is easily one of the most expansive, optimistic, and uncritical bodies of work in American poetry—transcribing the real as O’Hara saw, heard, tasted, and felt it, scribbled off quickly in lunchtime poems with almost no revision. Like the French imagists (Verlaine and Rimbaud) or the West Coast beats, O’Hara inspired readers to enjoy him at his own pace, and for his own idiosyncratic gifts—and the greatest of those gifts seemed to be the ability to write poetry that didn’t seem like poetry so much as the random expressions of a delighted, bemused life. As no less a personage than the sun tells him in “A True Account of Talking to the Sun at Fire Island”: “You may / not be the greatest thing on earth, but / you’re different.” And it was his sharing of his peculiar “different”-ness—as well as his passions for Mayakovsky, Rachmaninoff, smoking, drinking, and making love—that made his poetry feel like sharing, as Calhoun puts it, “a wonderful secret.” Like Pollock (the subject of O’Hara’s 1959 monograph for Braziller), he didn’t produce works to be hung in some impersonal museum; he preferred to get down on the floor and play around with the daily experience of producing them.

Every poem O’Hara wrote was an occasion for readers to join him in the unremarkable pleasures of living. In an apocryphal anecdote, Jack Kerouac drunkenly heckled O’Hara during a reading: “You’re killing American poetry, O’Harry.” To which O’Hara reportedly replied: “That’s more than you could do.” It’s hard to think of Frank O’Hara taking something called “American poetry” very seriously. And for O’Hara, it certainly wasn’t something that merited either being killed or saved. It was more like an intimate medium of human exchange.

O’Hara often collaborated with others—for example by writing poetic captions to a book of black-and-white drips and splashes by Norman Bluhm titled Poem-Paintings, or modeling for portraits by his friends Larry Rivers and Grace Hartigan, among others. And when friends weren’t appearing in his poems, they served as occasions for writing them, as in “3 Poems about Kenneth Koch” or “A Note to John Ashbery.” Unlike the beats, who might glamorize their claustrophobic little in-group as “the best minds” of their “generation” and so forth, O’Hara never seriously suggested that his clamorous fellow artists were any more enlightened than himself, just as his poems never presume to mean anything but themselves. Recording the latest events and conjectures with an almost diary-like nonchalance, each poem simply needed to be. And remind everyone what had happened before the next poem came along.

For O’Hara and his peers, poetry was lived rather than composed. As Schjeldahl explained in one of the taped interviews he passed on to his daughter, O’Hara provided an “option for a lifestyle for poetry that had not existed up to that time. At that point, the only lifestyle was the university.” As he went on: “I’m a poet. Dropped out of college. I came to New York. And I’ve made my living writing art criticism ever since, which was an option created by Frank and John [Ashbery]. It didn’t exist before.” It’s a vision of arts and letters that is increasingly hard to sustain in the era of wildly fluctuating Manhattan rents—the idea that you can produce uncommercial work while still managing to live in a stable, comfortable apartment, spend a large part of the day unprofitably reading and writing, and still afford regular nights out at the local bar with your friends.

But this is only partly a book about Frank O’Hara. For Calhoun, the biography project was also about working through her relationship with her father. The bond was, for several years, an uneasy one. When Calhoun was a child, she recalls, her father worked quietly in his study until three, and had little if anything to say when she came home from school, since he was diligently awaiting the strike of five o’clock when he could start drinking. In the art-filled apartment they shared, with its crowded bookshelves and its view of St. Marks Place many elevator-less floors below, there was something missing.

The small breakthroughs in their relationship came through literature. “In one of my mother’s efforts to have my father pay more attention to me,” Calhoun recalls, “she sent him out to get me something. He came back from the Strand Bookstore with a stack of books, including W.H. Auden’s The Dyer’s Hand and Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems.” Like many people who love books, reading isn’t always about accepting wisdom and beauty from some writer or artist more exalted than ourselves; for many of us, as for Ada and her father, it is often a relatively mundane form of human intercourse.

Calhoun gets to work on the abandoned biography, intending to “succeed” where her father “failed.” Yet she finds the project less promising than she had hoped. In her father’s cardboard boxes, she finds treasures: taped interviews with O’Hara’s friends, from Frank’s siblings to Karen Koch (widow of Kenneth), Ron Padgett, Edward Gorey, and O’Hara’s longtime on-and-off again lover and friend Larry Rivers. But she also finds crude little realities of history that just don’t jive with her love of O’Hara. Her explorations start to sound a little like Alison Lurie’s lovely The Truth About Lorin Jones, in which a biographer loses affection for her idealized subject the more she learns about her actual life.

In this case, it’s not O’Hara himself who loses luster but rather his friends and colleagues—some of whom, to put it mildly, don’t “date” well. For example, there are Larry Rivers’s fond memories of seducing a friend’s teenage daughter—which do not charm Ada, who grew up with creepy men following her home in Manhattan. And then there are the recollections of bruised wives out picking up alcohol for their artistically self-involved husbands. In retrospect, maybe not so amusing.

She also quickly comes up hard against the same spiny obstacles that confronted her father years before. The literary estate, overseen by O’Hara’s sister, seems uncomfortable with the idea of a “biography” that might be more about Calhoun’s family members than it is about her own. As a result, Calhoun grows wary of quoting from O’Hara’s poetry—referring instead to lines from her father’s work, or from Shakespeare and Ben Johnson. (At one point, she simply tells the reader the title of a favorite O’Hara poem and advises: “Google it.”)

Eventually, the work left uncompleted by Calhoun’s father begins to look innately uncompletable. Calhoun’s book diverts itself from literary history into memoir, as Calhoun explores how we grow up with writers and poets who often feel more intimate and reliable to us than our own family and friends.

As Calhoun’s biographical aspirations fade, she feels just as much a failure as her father—at which point life, as it very often does, intervenes. Her father is diagnosed with cancer and refuses to accept the news as a reason to quit smoking. (Smoking and writing every morning is, he claims, just what he does.) Covid arrives; Manhattan’s street energy dissipates; and longtime beloved family hangouts, such as the Odessa, close. Last but not least, after a fire burns through Ada’s parental home on St. Marks, her family’s coveted books, keepsakes, and photos are either deteriorated or covered over with a greasy gray oil. And a book about recovering the fragile past turns into a book about losing much of it.

Despite their shared commitment to O’Hara, Calhoun’s relationship with her father remains as fraught as ever. At one point, she suffers what seems like a disproportionate amount of pain and rage when she learns her father threw away a special book she once bought him for his birthday. He seems to her just as uncertain as ever about who she is, and she grows almost as uncertain about who he is right back.

Like Mark Doty’s What is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life or Martha Ackmann’s These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson, Also a Poet isn’t about the study of poetry so much as about living with it—and this energetic living with poetry was something that Frank O’Hara very industriously did. Like Ada and her father, he walked and drank and partied and read and wrote and made love; he exulted in the beauties of streets and cities and rarely had anything negative to say about any of them.

O’Hara never seemed to give up on the exultant life, and it is perhaps one of the greatest and saddest ironies of contemporary poetry that he died so young, and so unexpectedly. Like all lives, his was a messy one; but at times, no life seemed more gloriously messy than his. And it is the glorious messiness of O’Hara’s life (and of Ada Calhoun’s own) that this little book captures elegantly and transparently without ever aspiring to capture something as fragile and pointless as “literary greatness.”