Robert McNamara was one of Camelot’s most inglorious bureaucrats, but he also counted as among its most enduring. His résumé, prior to entering the Kennedy administration in 1961, is known better than that of perhaps any other Cabinet secretary of the postwar period. From studying at Harvard Business School to planning bombing sorties in World War II, he subsequently rose to the role of CEO of Ford Motor Company before his selection as secretary of defense. At the Pentagon he lasted an interminable eight years, and the Vietnam War transformed his reputation from that of an efficient pencil-pusher to something far more nefarious. Younger generations, of which I count myself a member, first learned of McNamara from Errol Morris’s Oscar-winning 2003 documentary, The Fog of War, in which McNamara took responsibility but did not apologize for the execution of the Vietnam War.

Philip Glass’s memorable score to that movie has perhaps blotted out McNamara’s ignominious excuse-making for his Defense Department. When Morris asked him why he hadn’t spoken out against the Vietnam War when he resigned in 1968, over seven years before the fall of Saigon in 1975, McNamara replied, “These are the kinds of questions that get me into trouble. You don’t know what I know about how inflammatory my words can appear.” Somehow making a flippant plea for mercy, he explained, “A lot of people misunderstand the war, misunderstand me. A lot of people think I’m a son of a bitch.”

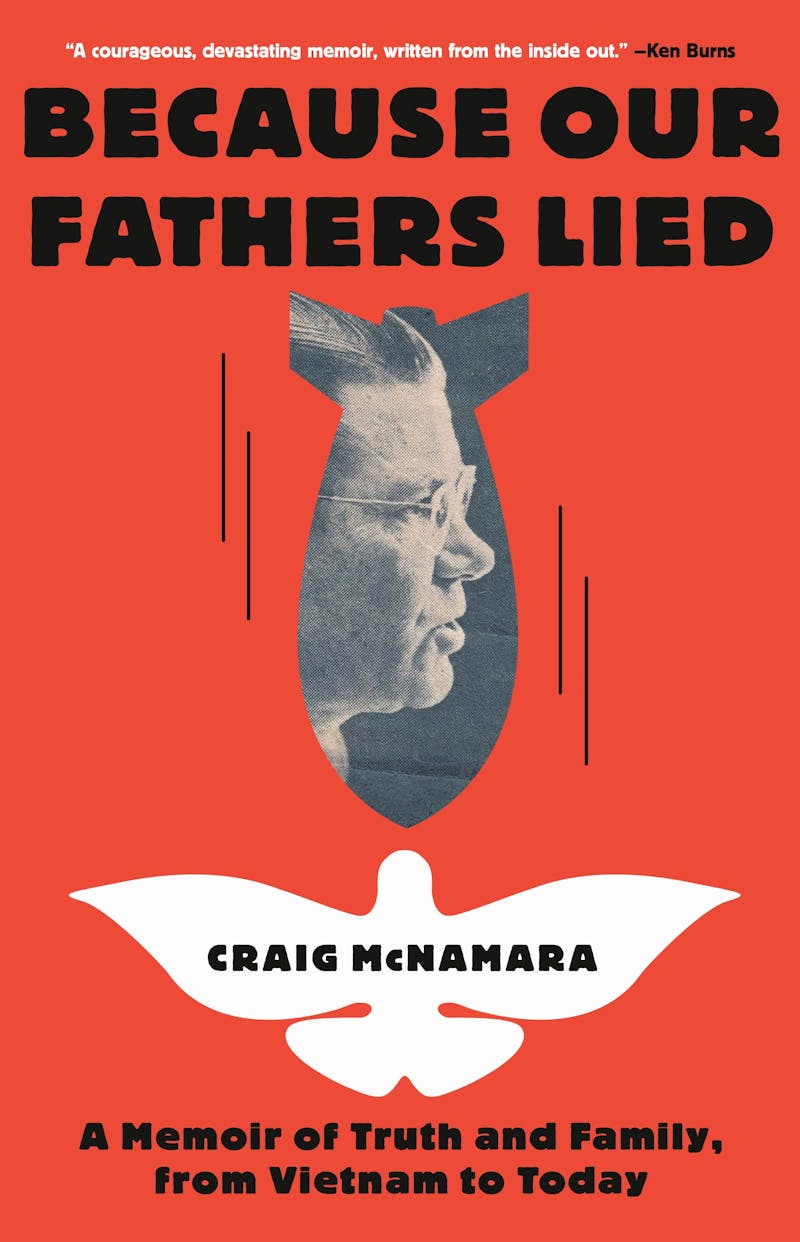

Craig McNamara does not use those words about his father—he’s much too gentle—but he would probably understand the sentiment. His new book, Because Our Fathers Lied, is a valiant and abrasive attempt to sift through a legacy his father refused to abjure. If Camelot really was a kind of court of midcentury kings, a high watermark for liberal capitalism distant from our moment of fracture, how fortunate we are to have such a thoughtful account of that world from someone who was born into it. Unlike many memoirs from this milieu (With Kennedy, A Thousand Days) and journalistic treatments of it (The Best and the Brightest, The Dark Side of Camelot), Craig McNamara’s book evinces the sort of hippie humanity that his dad, in his own way, worked to squash.

You can tell Craig McNamara means business because he directly links his formative experiences with geopolitical explosions, the elite class of U.S. bureaucrats reacting to them, and how these encounters might connect to the lives of their children. After attending day school in Washington, D.C. (Sidwell Friends), Craig McNamara began boarding school (St. Paul’s) in 1964—the same year, he notes, as the Gulf of Tonkin incident that precipitated the American escalation in Vietnam. Despite nearly flunking out of school due to undiagnosed dyslexia, he went to Stanford, a set of experiences he recounts with maturity and clarity. “It was pretty damn discouraging to get poor grades while being the son of someone who was considered a Whiz Kid and one of the sharpest minds of his generation,” McNamara writes. Along with his friend Graham Wisner, the son of a legendary CIA official who killed himself in 1965, Craig was sent by the school to see a psychotherapist, part of what he calls his initiation into the “slow, forever-burning grief that enshrouded Robert McNamara’s ongoing life.”

Craig McNamara’s elegant and spare descriptions of St. Paul’s (“The idea there was to turn yourself into an increasingly bright and shiny object”) give early indications that he might one day radically depart from his father’s expectations. At home, Dad didn’t talk about the war, a practice internalized by the rest of the family. “I didn’t express myself at boarding school, but in my bedroom at home during the summers, where my father might see them, I began my earliest protests,” McNamara writes.

“I remember, as early as age thirteen, having questions about my father’s integrity,” he writes, recalling a March 1963 Newsweek article about the elder McNamara. That year saw congressional hearings regarding Dad’s award of a controversial $6.5 billion military contract—the TFX fighter plane—to the Texas-based firm General Dynamics, then closely associated with Vice President Lyndon Johnson. “Three times the Pentagon’s Source Selection Board found that Boeing’s bid was better and cheaper than that of General Dynamics and three times the bids were sent back for fresh submissions by the two bidders and fresh reviews,” the journalist I.F. Stone later wrote. “On the fourth round, the military still held that Boeing was better but found at last that the General Dynamics bid was also acceptable.”

It was the summer of 1967, however, when “everything changed” for Craig. He was on a family visit to Aspen, Colorado, when a group of antiwar protesters appeared in the meadow outside their house. Craig took a copy of a famous peace poster by the artist Thomas Benton, depicting three doves flying toward the sun (the image that provides the clear inspiration for the cover of Because Our Fathers Lied). After that, nothing was the same:

I was becoming one of the people in the meadow. The feeling I had was solidarity with them. The protesters were there to talk to my father about the war, and he had ignored them in much the same way he ignored me. The inspiration of that evening still grows wild in my heart, like the paintbrushes in the meadow. But the memories are wilted and picked over. I’m not exactly sure what I was thinking at that moment, when I turned my back on my parents and stayed outside. It felt natural, almost accidental, because intrinsically I knew the war was wrong. I couldn’t push against my own heart.

Craig McNamara didn’t serve in the Army himself, disallowed from going to Vietnam because of stomach ulcers. “Not going to Vietnam as a soldier still causes me overwhelming guilt,” he writes of his teenage feeling. “It’s like a gap in my soul.”

Instead, after graduating college, he embarked on an ill-advised motorcycle trip south, riding through Central America all the way to Chile, where he got into a situation that reads like the plot of Out of Africa mixed with Reds. Entranced by a speech from a visiting Fidel Castro in Santiago, Craig fell in love with a Chilean woman and lived for a while as a farmer on Easter Island. He returned home to the United States for the first time in years shortly after President Salvador Allende was assassinated and his socialist government overthrown in a coup on September 11, 1973. Even on this journey of personal and political discovery, however, he found himself squarely within a realm where his father held authority: The trip coincided roughly with his father’s appointment as president of the World Bank—the globe’s preeminent financier of development in the global south.

After General Augusto Pinochet seized power in Chile in 1973, the country began a campaign of privatization. McNamara’s World Bank played a role in mediating the Pinochet regime’s finances, helping to stabilize the budget (and its need for enhanced military expenditures) while assisting in the servicing of Chile’s foreign debt. “When he came under criticism years later for allowing the Bank to favor the brutal Pinochet regime,” fils notes, père’s response was to deny that “civil rights” influenced World Bank lending. “Looking at his quote now, I find it to be an abhorrent evasion,” McNamara reflects. “To me, this is an example of a lie. It was a deliberate evasion, a strategic silence. Just as he had at the Pentagon, Dad sang the official line of that cruel Chilean policy.”

American foreign policy often seems primarily composed of these moments, of going along and getting along with powerful interests, with the less said, and less thought, about it the better—unless career advancement, or one’s own neck, was on the line. “His loyalty was a kind of corporate loyalty,” McNamara writes of his father. “If he thought the war was wrong but couldn’t buck the system, then he should have left the system. He did not. Instead, he waged war. Afterward, he didn’t say he was sorry. To me, this is the truth about his loyalty.”

What Craig really took from his time in Chile was not political; it was agricultural. Upon returning to the U.S. he moved to Davis, California, and studied farming. Eventually, with financial help from his dad, he bought a walnut farm, a business he has tended to over the past 40 years. Having seen a master of the universe attempt to organize the world, with either disregard for or ignorance of his actions’ outcomes, the son fucks off back to the land. Running away from Robert McNamara and into nature was good for Craig’s soul and formed the basis of his own worldview, in which the highest concerns were providing food and water for all of mankind; restoring human harmony with the natural world; and, above all, an end to the exploitation of agriculture in the developing world.

Robert McNamara was a hiker, skier, and a liberal “conservationist,” but he and his son never grew too much closer. After 1963, “my father’s relationship with Jackie [Kennedy-Onassis] grew stronger every year,” McNamara observes. “But that’s precisely the point: Dad rarely extended his personal life to me. The death of Craig’s mother, the intra-family emotional conduit, in 1981, foreclosed any possibility of a major reconciliation of views. So too, I imagine, did the revelation of Dad’s favorite dessert: “Only two triangular pieces, please,” of Toblerone chocolate. And then, the final understanding and intimacy accompanying Robert’s death in 2009, and the 2022 publication of Craig’s memoir.

Because Our Fathers Lied is a captivating text for anyone grappling with the pain of possessing a parent who did horrible things. It is also a charming account of a long-since-dead international liberal aristo-bureaucracy. That a son published such a loving denunciation of his father is fairly astonishing. Craig McNamara evidently developed an autonomous morality at a young age, no easy feat in the heart of the American upper crust’s inner sanctum: the intersection between Washington and big business. This was a world where, as midcentury sociologist C. Wright Mills wrote in The Power Elite, “the most impersonal problems of the largest and most important institutions are fused with sentiments and worries of small, closed intimate groups.… In such circles, adolescent boys and girls are exposed to the table conversations of decision-makers, and thus have bred into them the informal skills and pretensions of decision-makers,” writes Mills. “Without conscious effort, they absorb the aspiration to be—if not the conviction that they are—The Ones Who Decide,” Mills finds. This social conditioning didn’t work on Craig. He understood the inner life of a decider all too well.

It was scholastic ineptitude, perhaps, that saved him from a life spent making the name “McNamara” a dynasty like that of other epic American blue bloods: Dulleses, Bushes, and Kennedys. Ethical, social and, eventually, financial self-sufficiency made Craig McNamara immune to perhaps the worst quality visited upon the children of the rich in the course of their rearing: mindless ambition.