Around midnight on May 19, 1990, a 15-year-old boy named Recco Rogers was shot fatally on the front steps of a friend’s house at 5607 Labadie Avenue, in the Wells-Goodfellow neighborhood of St. Louis. An enclave of modest brick homes and apartment houses seven miles northwest of downtown, Wells-Goodfellow was first settled around the time of the Civil War. It thrived alongside nearby factories during the early twentieth century and, like other areas in and around North St. Louis, including Ferguson, declined after World War II. White flight, redlining, deindustrialization, and municipal neglect begat a violent drug trade. By 1990, the sound of gunfire was common in Wells-Goodfellow. Hearing the shots that killed Rogers, some neighbors did not bother even to look outside.

The St. Louis Police Department received a call about the shooting just after midnight, and officers arrived on the scene shortly thereafter. Two homicide detectives, Gerald Brown and Gary Stittum, assumed control of the investigation. Squad car spotlights lit the scene; a crowd of onlookers gathered. Rogers lay unconscious, faceup on the lawn, bleeding from a wound behind his left ear. A bullet was lodged in his brain. An ambulance drove Rogers to Barnes Hospital, four miles away, where he died soon after being admitted.

In 1948, a duplex on Labadie Avenue was at the center of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Shelley v. Kraemer, which held that enforcing racially restrictive real estate covenants in court violated the Constitution. Now, fewer and fewer people wanted to live there. As Brown and Stittum canvassed the neighbors, they found relatively few potential witnesses.

A solidly built Black man, Stittum had been on the police force for 12 years and prided himself on his ability to establish rapport with even hardened criminals. That evening, however, his most fruitful conversations were with DeMorris Stepp, 14, and Michael Davis, 12. Stepp told Stittum that he, Davis, and Rogers had been talking on the front steps of 5607 Labadie when he heard a single gunshot. Turning, Stepp said, he saw a man dressed in a white T-shirt and blue baseball cap firing a gun from an adjacent yard. Hearing a second shot, Stepp bolted down the steps, hopped two fences, and sprinted down the street. Davis, meanwhile, said that after the first shot, Rogers fell to the lawn. Davis threw himself beside his friend and played dead. From the ground, Davis said, he saw a man wearing a white T-shirt and sunglasses in a neighboring yard. Both he and Stepp identified the man as Christopher Dunn.

Dunn, 18, was familiar to police who worked Wells-Goodfellow. Tall and slender, with pronounced cheekbones, light brown skin, and reddish hair, he cut a distinctive figure in the neighborhood. He had recently completed a brief prison sentence for cocaine possession and receiving stolen property. Dunn grew up a few blocks from 5607 Labadie, and within two hours of Rogers’s murder, law enforcement was at his house.

According to Stittum’s police report, Dunn’s mother, Martha, told detectives that her son was not home and allowed them to search his room. Later, the police returned to collect clothing they believed Dunn wore on the night of the murder, including a white T-shirt and a blue baseball cap. On the basis of Stepp’s and Davis’s statements, a warrant was issued for Dunn’s arrest.

The following afternoon, the police tracked Dunn to the home of a friend, a young woman named Frankie Young. According to the police report, they’d been told that Dunn was armed. While the officers were outside, Dunn left the Youngs’ house through a back door. In a rear alley, he was spotted by Sgt. Robert George. Seeing George, Dunn ran east, leaping several fences. George put out a call on his radio, and a second officer, Jerome Billings, apprehended Dunn after a foot chase, cuffed him, and escorted him to a police car.

The St. Louis Circuit Attorney, as the city prosecutor is known, charged Chris Dunn with first-degree murder, assault, and weapons offenses. Dunn denied the allegations, insisting that, as far as he knew, he’d seen Rogers just once in his life, and that he did not know Stepp and Davis at all. His puzzlement deepened when, weeks after his arrest, police again descended on his mother’s home: Someone had fingered him in another shooting, which occurred while he was in jail.

That July, Dunn got a letter from Janis Good, the Missouri state public defender assigned to represent him. He was determined to fight the charges. “I wasn’t going to let them railroad me,” Dunn said. But he was not optimistic about his chances at trial.

In addition to his adult convictions, Dunn had twice served time in juvenile detention on dubious charges. His father, Douglas, often felt harassed by the police—for burning leaves in his yard, or organizing a parade without a permit—and he sometimes intervened when he disliked the way a patrol officer was talking to his neighbors. In the 1950s and ’60s, North St. Louis police referred to Southern Black migrants as “Swamp Turkeys”; Dunn and his friends viewed the cops as occupiers.

Dunn provided Good with a list of alibi witnesses, but when they finally met in person, in March 1991, she didn’t appear to have made any progress in her investigation. A few months later, she encouraged Dunn to plead guilty to second-degree murder in exchange for a reduced prison sentence. Insulted, he refused. “Ain’t no way in the world you gonna force me to say I did something I didn’t do,” Dunn told me.

At the time, the Missouri State Public Defender was among the most poorly funded such offices in the country; until recently, Missourians charged with crimes sometimes waited years to be assigned a public defender. Missouri defenders were paid significantly less than their prosecutorial counterparts; worked out of rundown, outdated offices; and labored under workloads that often rendered meaningful investigation of their cases impossible. Many who took jobs with the office quickly quit, and they had few lawyers with the experience to properly defend serious felony cases, of which there were many: In 1991 and again in 1993, St. Louis clocked historically high murder rates.

“It’s fairly indisputable that the quality of representation is significantly subpar,” Megan Crane, a co-director in the Missouri office of the MacArthur Justice Center and the founder of the Missouri Wrongful Conviction Project, told me. “I have yet to see a case of innocence in Missouri where there is not at least one strong claim of ineffective assistance of counsel—and likely many more.”

By her own account, Good handled about 50 felony cases a year, roughly 15 of them murders. Employed by the Missouri State Public Defender’s office since 1984, Good, who died in 2013, was experienced, but Dunn found her poorly suited to the job; reluctant to visit the Wells-Goodfellow neighborhood, she ultimately interviewed only two potential witnesses in person. She told Dunn that she couldn’t find other people on his list. On July 12, three days before trial, Good and an investigator from her office met with Dunn at St. Louis City Jail. According to Dunn, she had spent no more than 15 minutes with him and had prepared no defense.

“Chris was hostile from the onset of the visit,” the investigator noted in a memo. Dunn denied allegations by Stepp and Davis that he was a member of the Crips gang; he urged the investigator to canvass his neighborhood in search of potential suspects and motives for the shooting. “I explained to Chris that my job here was not to find warring gang members, but asked him to specifically tell me who [sic] to talk to and what gang he was in,” the investigator wrote. Testifying in a posttrial hearing, Good explained, “My discussions with everyone … indicated that it was a gang shooting.”

Dunn felt typecast. “You assume that every Black person in the neighborhood is in a gang,” he recalled thinking. “I tried to explain that even though I lived in that community, it didn’t mean that I was like many other people in that community.” The investigator’s notes on the meeting conclude, “After 10 minutes, [Dunn] got up from the table … and stormed off.”

Testimony in Dunn’s trial lasted just one afternoon. Neither Stittum, the detective, nor Steven Ohmer, the prosecutor, offered a motive for the crime, and no one who testified described a conflict between Dunn and Rogers. On the stand, Michael Davis called Dunn a “friend”; DeMorris Stepp testified that although he had seen Dunn around, they didn’t speak to each other. He also acknowledged that by cooperating with the prosecutor, he hoped to improve his chance of getting probation for pending charges related to an armed robbery. (At the time, prosecutors in Missouri had tremendous discretion with regard to charging juveniles as adults.)

Ohmer presented no physical evidence. The clothing collected from Dunn’s mother’s house never appeared in court, and a revolver recovered from a vacant lot near Frankie Young’s home around the time of Dunn’s arrest had not, apparently, been used to shoot Rogers. Having concluded that Dunn’s potential witnesses were unreliable, unavailable, or otherwise ineligible to testify, Good did not call any in his defense. Ohmer, in his brief closing argument, repeatedly emphasized that the testimony of the state’s witnesses was “uncontradicted.”

After less than 45 minutes of deliberation, the jury found Dunn guilty on all counts. His record made him subject to Missouri’s three-strikes law, and the judge, Michael Calvin, sentenced him to life without parole, plus 90 years. It would be nearly three decades before another court consented to closely reexamine the case. By then, amid a nationwide wave of exonerations—the result of DNA analysis, reevaluations of investigative methods, and a reckoning with systemic biases—Missouri had become perhaps the most difficult place in the country for an innocent person to get out of prison.

In recent months, I spent many hours talking with Dunn, a warm, voluble, inquisitive man with a musical St. Louis drawl and a knack for telling stories from his past that are at once dreamy and sharply detailed. Befitting a person long accustomed to being disbelieved, he begins many sentences by saying, “To be completely honest with you.” During one phone conversation, he recalled leaving the courtroom after sentencing: “As I walked through the pews, I seen my friends on the left and my mother on my right. It looked like she was getting ready to cry. I had to stop and smile and let her know that I’ll be all right. When I got back in that bullpen, every tear that was in my body came out. I just knew it was over with.”

In recent years, prisoners like Dunn, convicted under questionable circumstances during the nation’s long incarceration boom, have become a cause célèbre for left-leaning prosecutors, including Larry Krasner in Philadelphia and the recently recalled Chesa Boudin in San Francisco. In 2016, Kimberly Gardner, a Black progressive, was elected chief prosecutor in St. Louis and established the state’s first Conviction Integrity Unit, or CIU.

Together with innocence organizations, CIUs are now a factor in a majority of exonerations. According to an April 2022 report by the National Registry of Exonerations, they “play[ed] essential roles” in 97 of 161 exonerations nationwide in 2021. But CIUs depend on the support of courts and elected officials, which varies dramatically among states. Last year, five states accounted for 54 percent of the total, with Illinois topping the list at 38 exonerations. In Missouri, which had just one, the attorney general’s office has opposed prayers for relief in virtually every wrongful conviction case since 2000. “Some are trying to de-incarcerate, and some people invested in the status quo are trying to clip their wings,” Miriam Krinsky, the executive director of Fair and Just Prosecution, a progressive prosecutors’ group, told The New York Times in 2019.

Eric Schmitt, the current Missouri attorney general, has vehemently opposed efforts to reverse past convictions. Like his predecessor, Senator Josh Hawley, Schmitt—now running for Senate himself—is a Republican in the Trumpist mold. Gardner’s election, together with the subsequent elevation to public office of other Black progressives—including Cori Bush, of St. Louis, to the House of Representatives, and Wesley Bell, to the head of the St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office—highlight Missouri’s stark embodiment of the country’s larger urban-rural divide.

Sean O’Brien, a veteran defense lawyer in Kansas City, has argued death penalty and innocence cases across the country, including before the U.S. Supreme Court. “Missouri is very much a rural, Southern state,” he told me—no different, in matters of criminal justice, “than Alabama or Mississippi.” O’Brien explained, “Crime has become a surrogate for race.”

Martha Dunn, Chris’s mother, was born in 1951 in a small town in the Mississippi Delta, the fourth of 11 children. Her parents worked on plantations—her father at the wheel of a tractor, her mother picking cotton. When Martha was 16, her older sister Lula went to visit an uncle in St. Louis and stayed for good. In 1969, Martha joined her.

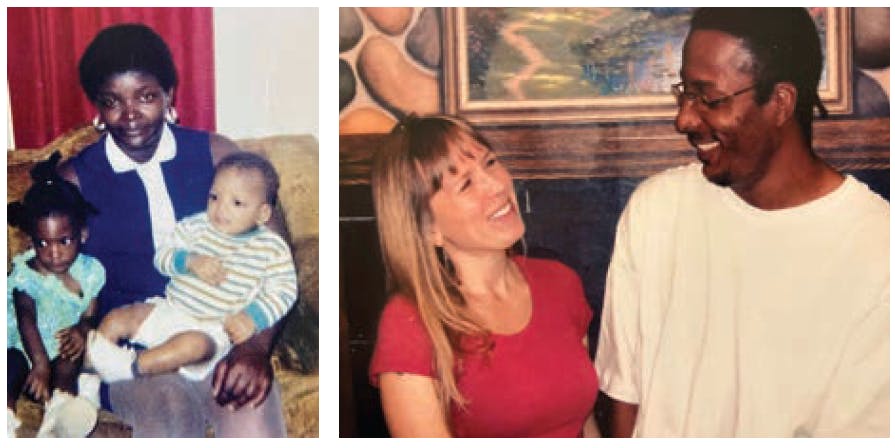

Before long, she met William Douglas Baker, who lived four blocks from her sister’s place. Martha recalled, “We started talking, I moved in with him, then the kids came along.” Angela was born in 1970, followed by Chris, Delores, and Arnetta. (Baker went by his middle name; Martha’s children took her last name.)

Martha and Douglas got jobs with the St. Louis Public School District, in food and janitorial services, respectively. In 1979, the family moved from a public housing complex to a single-family home in Wells-Goodfellow. The residence, a stately brick house with rectangular columns and a neat green lawn, was the first they had owned and a source of pride. Martha and Douglas spent years making repairs and improvements. The neighborhood was poor, but bound by a strong sense of community. Single mothers struggling to make rent were the beneficiaries of garage sales and one-dollar basement parties. A handful of older couples, who had been there for many years, imparted warmth, dignity, and discipline. One, the Williamses, who lived next door to the Dunns, could be relied upon to report back to Douglas and Martha about unapproved guests who visited while they were at work.

As a child, Chris Dunn suffered from eczema and had few friends, but he possessed a talent for drawing. His 25-foot-long homage to The Last Supper, peopled with cartoon characters, hung in the hallway of his elementary school. Dunn did well academically, too, spending only a few months each in sixth and seventh grade before being fast-tracked into eighth.

By high school, his skin was improving, and the family home was a gathering place for local kids. Martha told me, “They could eat, sleep there. [Douglas] was crazy about trying to keep kids out of trouble.” But in the mid-1980s, as drugs and violence grew prevalent, older families moved away, and the sense of mutual support that had united Wells-Goodfellow frayed. Dunn said, “It went from a community to a neighborhood, from a neighborhood to just a ’hood.”

Following Dunn’s trial—and having offered no proof of it in court—the prosecutor told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that Recco Rogers’s death was the result of a conflict between gang “wannabes.” People who knew Dunn well were incredulous. Shuron Williams, who was several years behind Dunn in school, said that he stood out among his peers. “He was one of maybe two guys in the neighborhood who didn’t join a gang or sell drugs,” Williams, who later became a Blood—and who is now married, with a warehouse job—told me. “Chris was always trying to keep me out of trouble.”

Maurice Freeman, a childhood friend, said that even when a situation required force, he never knew Dunn to reach for a weapon. “We wasn’t into guns,” Freeman told me. “Chris was a good enough fighter to where he didn’t have to pick up a gun.”

In 1999, Kira Caywood, a volunteer with a nonprofit magazine called Justice Denied, was assigned to write an article about Dunn’s case. The magazine, which sought to draw attention to wrongful convictions, had been alerted to the story by a North Carolina couple with whom Dunn had been corresponding, after they connected with him through a Christian nonprofit.

The Innocence Project, the organization founded in 1992 by Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, had begun to help increase public awareness of wrongful convictions in the United States. Between 1989 and 1999, the first decade for which the National Registry of Exonerations analyzed data, it was reported that more than 400 prisoners nationwide were determined to be innocent and released. But at that point, the exoneration movement was in its infancy; in 1999, just 59 convictions were overturned nationwide, compared with more than 160 last year.

Kira was 29, two years older than Dunn. The mother of three children, she had a corporate job near Sacramento, California, and worked nights and weekends for the magazine. She had become focused on the problem of wrongful convictions after reading a 1998 article in Time about Shareef Cousin, a Louisiana teenager who spent years on death row for a murder he didn’t commit.

Kira found that Dunn and Cousin had similarities: Both were Black and had been convicted without physical evidence, based exclusively on eyewitness testimony. (According to the National Registry of Exonerations, perjury or false accusations are involved in about 61 percent of wrongful convictions; mistaken eyewitnesses are a factor in some 27 percent.) The witnesses against Dunn, Michael Davis and DeMorris Stepp, were children at the time of his trial, vulnerable to manipulation by prosecutors and police. There was only one Black person on Dunn’s jury, and Kira, who is white, was struck by how quickly it had reached its verdict.

In 2000, Kira visited Dunn at Missouri State Penitentiary, in Jefferson City, and later published an article in Justice Denied that raised questions about his case. By then, Dunn had exhausted a number of post-conviction remedies. His motion for a new trial, filed soon after his conviction, was denied. Subsequent motions and briefs in state court were rejected. In 1997, Dunn filed a habeas corpus petition in federal court. Three years later—the same month Kira’s article came out—that, too, was denied.

Unless highly exculpatory new evidence emerged, no likely legal path remained to overturn Dunn’s conviction. But he was still optimistic and, to a degree that amazed Kira, did not seem defined by his imprisonment. He had pen-pal relationships with people all over the world—at one point, there were so many letters in his cell that corrections officials worried they were creating a fire hazard. He had completed his GED and received certificates for carpentry and tailoring. He loved books—The Grapes of Wrath was a favorite—and kept a list of those he’d read. His memory for the landscape of his past was astonishing: intersections and addresses and the quirks of neighbors; the sounds of Curtis Mayfield and Blondie on a sunny day in Visitation Park, when people were out in their Afros and Daisy Dukes and bell bottoms.

Prior to Kira’s visit, Dunn had been stabbed by another inmate. They continued to correspond while he recovered, and in 2004 she went to see him again; the following year, the long-term relationship she had been in dissolved, and her relationship with Dunn turned romantic. Her family was deeply skeptical, but they were accustomed to what they considered to be her unorthodox choices. A vegetarian, Kira was raised by grandparents in Arizona and has twice been a surrogate mother. She is petite and athletic, with long, light brown hair, and an air of empathic mindfulness of the kind sometimes associated with yogis and healers. She did not enter her relationship with Dunn lightly. “Chris had been disappointed so many times,” Kira told me. “I felt that this was going to be a commitment that I’m making for life.”

Meanwhile, Dunn had spent numberless hours poring over legal texts in the prison library and had collected affidavits from two men who’d picked up jailhouse chatter about his innocence. One, written in 1994, was from a man named Curtis Stewart, who, from late 1990 until September 1991, had been in jail with Stepp, the witness with pending robbery charges. Stewart wrote that he overheard Stepp on the phone saying that he “didn’t know who really killed ‘Recco,’” but “that the prosecutor will make a deal with me if I testify for the state.”

The other affidavit was from Dunn’s old neighbor Shuron Williams, who said that, during a jail stint, he was told by Dwayne Rogers, the murder victim’s older brother and a fellow inmate, that he knew who killed his brother—and that it wasn’t Dunn. In 2002, Williams signed a sworn statement to this effect.

Tantalizing as they were, these affidavits amounted to hearsay—not nearly enough to overturn a conviction. But in 1996, Stepp was convicted of murdering a young woman and sentenced to life in prison. Dunn began hearing rumors that Stepp was telling other prisoners he’d made a mistake testifying against him. In 2005, Dunn received an envelope in the mail from an inmate named Lawrence Anderson. Inside was an affidavit, scrawled by hand and apparently signed by Stepp. In disbelief, Dunn contacted Anderson, who told him that the document was real and promised to have the affidavit typed for court. Stepp was recanting his testimony.

The final version of DeMorris Stepp’s affidavit read, in part, “I lied on Chris Dunn, to save myself.... I was facing 15–30 years in prison so I was given a deal to lie.” He continued, “Michael Davis said it was Dunn because I said it was him…. It was not Dunn that committed the killing, and I, and God know it.”

Dunn was thrilled. He called Kira, who set about finding him a new lawyer. She and members of Dunn’s family chipped in to fund his defense—Kira eventually cashed in her 401(k)—and Susan Kister, a private attorney in St. Louis, was encouraged by Stepp’s statement. But without a recantation from the second eyewitness, Kister said, the chances of Dunn’s winning release were slim. “So we started looking for Davis,” Kira said.

She hired a private investigator named Dan Grothaus, who began to do for Dunn what the Missouri State Public Defender had not: lay the groundwork for a defense.

Grothaus met with Dunn’s mother, Martha, and his sisters, Angela, Delores, and Arnetta. (Dunn’s father died of cancer in 1989.) They all recalled being at home on the night in question, and that Dunn, typically, had been monopolizing the telephone. The night was warm. Some people had gone outside, and the women remembered hearing gunshots. Martha recalled saying, “These fools shooting, time to go in.”

Their recollections were corroborated by two women who remembered speaking with Dunn on the phone that night: Catherine Jackson, who was 16 in May 1990, told Grothaus that she and Dunn talked for 30 to 60 minutes beginning sometime between 10 and 11 p.m. In an affidavit, Jackson wrote, “I remember Chris Dunn was happy and acting normal. He did not mention having any altercation with anyone.” Nicole Bailey, who was 15 on the night of the murder, had just delivered her first child and was in the hospital, watching television. Bailey recalled, “I was on the phone with Chris Dunn from sometime after the TV Show Hunter began, and we stayed on the phone until a nurse came in an hour or two later to check on my ‘Vitals.’”

Hunter, a long-running crime drama, was a favorite of Martha’s. The women in Dunn’s family remembered that it was on at their house, too. In the archives of the St. Louis Public Library, stored on microfilm, Grothaus found the Post-Dispatch TV listings for May 18. Hunter had been on at 11 p.m. With Bailey’s permission, he pulled her medical records, which appeared to confirm her recollection of her conversation with Dunn. Her vitals had been checked at 1 a.m., an hour after Hunter ended. Grothaus said, “That’s starting to be a good alibi.”

But Davis was still among the missing. In 2008, Dunn had asked Kira to marry him, encoding the proposal in braille on the back of a paneled portrait he’d drawn of her children, whom he’d come to think of as his own. They waited, hoping to wed after Dunn’s release. Dunn drew portraits and cartoons, and decorated greeting cards and envelopes, selling them—mostly to other prisoners—for $3 to $50, until he had enough to buy Kira a half-carat stone. “I saved up every little dime I could get,” Dunn said. “I didn’t want her to go without a ring.” In 2014, tired of waiting, they wed in a ceremony at the prison with seven other couples. “There was no D.J., no music, no cake,” said Kira, who took Dunn’s surname. “But it was a beautiful day.”

In 2015, Grothaus hit upon an especially promising lead. Using Davis’s childhood address to search a database, he identified a woman who had also lived there and was of an age to be Davis’s mother. Her listed residence was in California, where, Grothaus saw, a Michael Davis Jr. also lived for a time. “Sure as shit, I knew that had to be him,” Grothaus said. In Solano County—coincidentally, not far from Kira’s home—Davis had amassed the sort of criminal record that suggested he might one day find himself in custody again. An ex–police officer she knew advised Kira to keep an eye on the county inmate registry. “I would check the jail logs every day, and then one Sunday morning, he popped up,” she said.

The Dunn camp couldn’t afford to fly Grothaus to California, so Kira hired a local P.I. named Craig Speck. One morning in November, he went to meet with Davis at the Solano County Jail. Within minutes, Davis had recanted. “In all actuality we didn’t see [Dunn] shoot,” he told Speck. “We didn’t know who the shooter was.… It could have been anybody.” In his telling, he and Stepp identified Dunn as the perpetrator almost arbitrarily: They believed he was a member of a rival gang, and that he’d been seeing a girl in their neighborhood. “It was just out of animosity we said it was him,” Davis explained. “We wanted somebody to pay.”

By the time of Dunn’s trial, Davis, who moved to California weeks after the shooting, had changed his mind. Rogers’s mother called him on the phone, “crying and talking about please get rid of this guy,” Davis told Speck. “I was still somewhat of a child, so I went with that to help her out. To keep her from crying.” He recalled that detectives told him: “You go in there and testify against him because this is what he did to your friend.”

Soon after Davis’s interview, Kira hired Kent Gipson, a prominent Missouri post-conviction attorney. In 2017, based on the evidence collected in the previous 12 years, Gipson filed another writ of habeas corpus, this time in state court. Most such petitions are denied without explanation. But in February 2018, Dunn got word that he had been granted a hearing to determine whether he was wrongfully imprisoned.

On May 30, 2018, the day of his hearing, Dunn was awakened in his cell at 5 a.m. and escorted to another housing unit of the South Central Correctional Center, where he had been held since 2010. Guards shackled his wrists and ankles, and he was loaded into a large white van with barred windows for the drive to Texas County Courthouse.

Texas County, Missouri, lies about 150 miles southwest of St. Louis and 80 miles north of the Arkansas border, at the heart of the Ozarks. Named in 1845 for the Republic of Texas, it is the largest county in the state and one of the poorest—a rugged, rustic place that would make a fine setting for a Daniel Woodrell novel. During the 15-mile drive to his hearing, Dunn took in rolling farmland punctuated by Confederate flags, a sight he found spooky but unsurprising. “I knew exactly what part of the country I was in,” he told me. Other prison towns where he’d been housed—Potosi, Bonne Terre—felt much the same.

At the courthouse, he greeted family members he hadn’t seen in more than 20 years. Seated at the defense table beside Gipson, Dunn could hear whispers of encouragement from the gallery: “We’re here to take you home today.”

But there was cause for concern. DeMorris Stepp, the first witness to testify, was seated on the same side of the room as Assistant Attorney General Andrew Crane. Since recanting his trial testimony, Stepp had provided yet another account of the events of May 1990—allegedly less favorable to Dunn—to an investigator from the attorney general’s office. Neither Gipson nor Dunn was quite sure what he would say.

On the stand, though, Stepp, now 42, hewed closely to what he wrote in his affidavit. In fact, he told the court, he had not seen a gun that night. It had been too dark on that part of Labadie Avenue to see anything but “a shadow.” It emerged in the course of his hearing testimony that during the trial, he had been facing not one set of armed robbery charges—as Dunn and his lawyer believed—but two. Appearing before the same judge who presided over Dunn’s trial, Stepp received a sentence of straight probation. Strikingly, the prosecutor in that proceeding, Steven Ohmer, the same one who tried Dunn, did not object. (Ohmer, who has been a state judge since 1994, declined to be interviewed for this article.)

Kira recalled that, as Stepp spoke, Judge William Hickle’s face reddened, and that the South Central Correctional officers who were in the courtroom approached the bailiff to ask whether they should prepare for Dunn’s release. “We thought, at this point, that he was going to walk out of there,” she said. “I had his clothes. We had planned his outfit.” Dunn could sense the mood in the courtroom shift in his favor. “I’m like, OK, this sound good—I might go home.”

Stepp was followed on the stand by Curtis Stewart—the man who, in the early ’90s, heard Stepp say he didn’t know who killed Rogers—and by Nicole Bailey. In an affidavit, Catherine Jackson explained that her mother, fearing for her safety, had forbidden her from participating in Dunn’s trial. (Michael Davis, still in jail, did not testify at the hearing.)

The final witness of the day was a man named Eugene Wilson, who had known Dunn since childhood. At the time of the shooting, he was living with the Rogers family. That night, he and another friend, Marvin Tolliver, whom Dunn also knew from childhood, were walking back to the porch of 5607 Labadie from a nearby Chinese restaurant when the shots rang out. Wilson told the court that, facing the shooter, he saw the flash of the gun’s muzzle—and nothing more. “You couldn’t see nothing but the fire,” he said. “Everything was like pitch dark, like you going camping and there’s not no moonlight.”

Wilson testified that, a few days before the crime, he, Recco Rogers, and others had badly beaten a man who’d assaulted Rogers’s mother. (In an interview with Speck, the investigator, Davis had said that Rogers had shot the man.) A month or two after Rogers’s death, Wilson said, Recco’s younger brother was murdered, too. Wilson confirmed that Dunn had no motive to shoot Recco Rogers: “Christopher Dunn don’t even know Recco…. Recco didn’t know Christopher Dunn from a can of paint.” The idea that Dunn would attack him or Tolliver appeared to strike Wilson as preposterous. “He would never shoot at me,” he said. “We grew up together.”

Until Grothaus tracked him down, in 2016, Wilson had never been formally interviewed about the murder. When Crane, the young assistant attorney general, pressed him about why he hadn’t come forward earlier, Wilson told him, “We didn’t do that on the Westside. We don’t help the police.”

In September 2020, more than two years after the hearing, Hickle released his judgment, writing that “new evidence has emerged, in addition to the recantations, which make it likely that reasonable, properly instructed jurors would find [Dunn] not guilty.” He continued, “This Court does not believe that any jury would now convict Christopher Dunn.” And yet, Missouri law prevented him from granting Dunn’s petition. Innocence alone, Hickle wrote, is grounds for relief only for a prisoner “sentenced to death, and is unavailable for cases in which the death penalty has not been imposed.” In other words: Dunn might have gone free, if only he’d been condemned to die.

The standard emerged from a 2016 Missouri Court of Appeals decision, Lincoln v. Cassady. In 1983, Rodney Lincoln, then in his thirties, was convicted of manslaughter and two counts of assault, and sentenced to life. Subsequent investigations, by the Midwest Innocence Project and others, found numerous problems with his case. False DNA evidence was presented at trial, and a key witness, a child, received secret coaching from the prosecution. Prosecutors withheld exculpatory evidence from Lincoln’s defense team. In a 2003 death penalty case, the Missouri Supreme Court had found that the “imprisonment and eventual execution of an innocent person is a manifest injustice.” The defendant in that case, Joseph Amrine, went free. But the Court of Appeals declared the Amrine decision irrelevant to Lincoln. “To avoid unending challenges to final judgments,” the court ruled, it could not grant a new trial in a noncapital case based on a prisoner’s actual innocence.

“Because the Constitution doesn’t literally say that we can’t kill or incarcerate you if you are innocent, then those events don’t qualify as a ‘manifest injustice’ within Missouri’s legal tradition,” said O’Brien, the Kansas City attorney, who represented both Amrine and Lincoln. No other state makes it harder for a person with a life sentence to get out of prison than for one sentenced to die. But the Kafkaesque logic at work in Missouri has deep roots in federal law. In 1993, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Herrera v. Collins that absent constitutional violations, new evidence of innocence does not entitle a prisoner to further judicial proceedings. In 2021, following Hickle’s decision, Dunn filed a habeas corpus petition at the Missouri Supreme Court, and Assistant Attorney General Crane leaned heavily on Herrera to argue against him.

Quoting Herrera, Crane wrote, “‘Due process does not require that every conceivable step be taken, at whatever cost, to eliminate the possibility of convicting an innocent person.’” That framework, he continued, “‘would all but paralyze our system for enforcement of the criminal law.’” Last August, the state Supreme Court refused to review Dunn’s case, seemingly confirming its support for the Lincoln decision.

Michael Wolff, a former Missouri Supreme Court judge who heard the Amrine case, believes that the Lincoln court misinterpreted the ruling. “If there is a remedy in a death case for somebody who’s actually innocent, then it strikes me logically that it ought to be available in cases where they got less than the death penalty,” he said. Still, Wolff acknowledged, the U.S. legal system often prizes finality over fairness. “Which value do you hold higher? The value of holding an accurate judgment, or a final judgment? The law has been fairly clear. In most instances, what we’re most interested in is finality.” O’Brien recalled a particularly dissonant exchange during the Amrine case. A Missouri Supreme Court judge asked Frank Jung, an assistant attorney general, “Are you suggesting … even if we find that Mr. Amrine is actually innocent, he should be executed?”

Jung replied, “That is correct, your honor.”

Dunn’s defense team recently filed yet another federal habeas corpus petition, but Gipson, his lawyer, told me that his best hope for release is now the St. Louis circuit attorney’s office. Last summer, the Missouri Senate passed legislation to allow local prosecutors to challenge past convictions, a mechanism long absent from Missouri law. In November 2021, Jean Peters Baker, the prosecutor for Jackson County, which includes most of Kansas City, used the law to overturn the murder conviction of Kevin Strickland, a Black man who had spent more than 40 years in prison. But that success came only after an exhausting battle with Attorney General Schmitt, who filed a series of motions that delayed Strickland’s exoneration and resulted in the recusal of all Jackson County judges from the case. Schmitt said that he was merely assuming his proper adversarial role. Despite the recantation of the sole living eyewitness and a lack of physical evidence, Schmitt insisted on Strickland’s guilt and accused Baker of misrepresenting the interests of the state.

“When the mistake does happen, even absent any kind of evil intent, it is our obligation to correct—the public needs to know we’ll do that,” Baker told me. “It’s the only restoration of the system.” She said the Strickland case shows Schmitt can be beaten.

But in the St. Louis area, Gardner’s CIU remains scoreless; Wesley Bell’s unit, too, boasts no exonerations. Recently, the U.S. Supreme Court appeared to affirm the mantra of “finality over fairness”: In a 6–3 decision in May, it ruled that state prisoners may not present new evidence in federal court in support of a claim that their post-conviction counsel in state court was ineffective and violated their constitutional rights.

When I spoke to her this spring, Gardner acknowledged that even in cases like Dunn’s, in which defense teams have developed convincing evidence of innocence, significant challenges remain. “We have to make an educated, independent investigation from the prosecutor’s standpoint,” she told me. “The stakes are high, not only for the integrity of the whole criminal justice system, but for the accused. We have to make sure we get it right.”

Sean O’Brien was more blunt. “Any prosecutor who invokes this statute is gonna have a fight on his or her hands,” he said. (Rodney Lincoln, who is white, received clemency, without being exonerated, in 2018.) In response to interview requests, a spokesperson for Schmitt’s office said in a statement: “The Attorney General was elected to do his job on behalf of the people of Missouri, and that includes upholding convictions obtained by prosecutors across the state.”

On a cold, sunny afternoon this past January, I rang the doorbell of a comfortable home in a leafy St. Louis suburb. Detective Gary Stittum, who retired in 2011, answered the door in a black tracksuit, his white-gray hair pulled into a ponytail. He said he didn’t remember the Dunn case but invited me in. In his living room, he squinted and frowned as I described the case. The details didn’t jog his memory—he estimated that he investigated 575 murders in his 18 years as a homicide detective—but Stittum seemed skeptical about the notion of wrongful convictions. “I guess killers want to be choirboys all of a sudden,” he said.

For two hours, as the sun went down, Stittum spoke about his time as a homicide detective. “The Wells-Goodfellow neighborhood was kill city back then,” he said, a locus of violence he attributed to lack of character. “Nobody had any perseverance—you look at the education level, the level of discipline of those households.” To illustrate, he pulled up an old crime-scene photo on his phone showing a mangled body and a bloody baseball bat.

I wondered what challenges working there had presented. But Stittum declined to name any. “You have to have a calling,” he said. “I had a true feeling about bringing closure, tracing a person’s last steps: What happened? Why did it happen?” He went on, “A good homicide detective has to do a profile of the deceased. What is the moment between the before and after? The moment between before and after is the truth.”

Yet in the Dunn investigation, the facts suggest that Stittum did none of the things he was describing. As I prepared to leave, he returned to the matter at hand. “[Dunn] can say whatever he wants,” Stittum said. “I don’t care. It seems like he had a weak-ass defense attorney. That’s not on me. My facts are the true facts.”

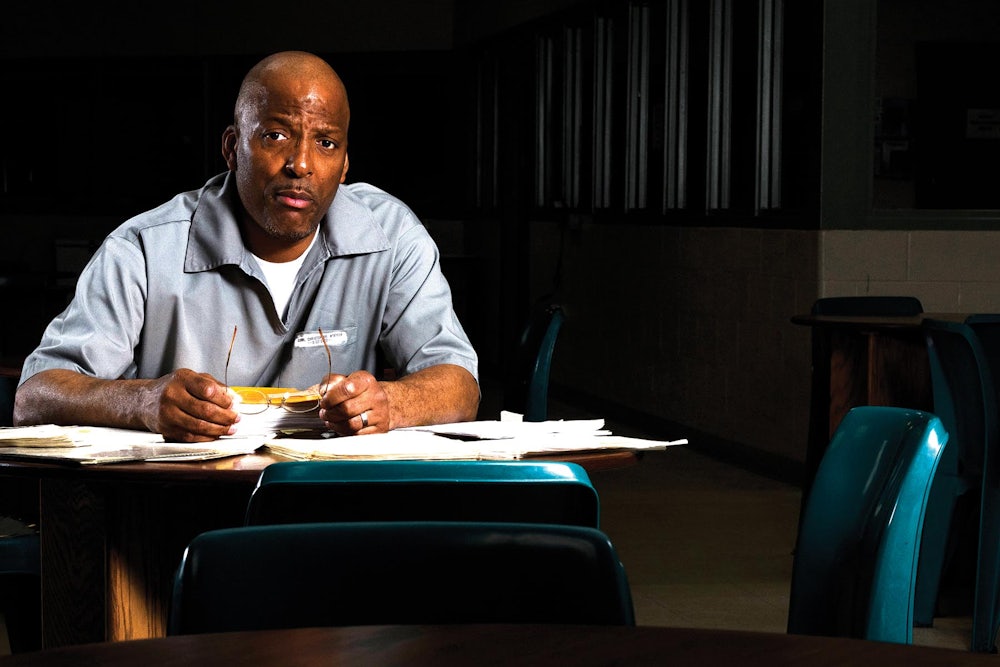

The visiting room at South Central Correctional Center resembles a public school cafeteria: unflattering overhead lighting, linoleum floors, banks of vending machines. One morning this past winter, I waited there for Dunn. Colorful murals depicting cartoon characters covered some walls. Off to one side stood a false backdrop of a rustic flagstone fireplace. I had seen the backdrop at Arnetta’s house a few weeks earlier, in a photograph of her, Dunn, and their mother taken over the holidays.

Dunn entered the room wearing short-sleeved prison grays, silver-rimmed glasses, bright white sneakers, and a cloth mask. Clipped to his collar was a plastic holder containing an ID stamped OFFENDER and a purple visiting pass. He was softer, less rangy than the young man I had seen in photographs, and he had lost some hair. Since being incarcerated, Dunn, now 50, has suffered three heart attacks, and the ID holder also contained a small bottle of nitroglycerin. We shook hands and sat down in green plastic chairs at a round wooden table. A stout, pleasant correctional officer in a black polo and gray chinos stationed himself nearby.

Kevin Strickland’s exoneration was celebrated in the national press. But Dunn sees Senate Bill 53, the law that enabled Strickland’s release, as a “Trojan horse”—a mechanism that allows the Missouri Supreme Court to avoid reversing the Lincoln decision. Gipson told me, “I’ve been taking cases up to the Missouri Supreme Court to get them to overturn that for four to five years. For whatever reason, they don’t want to address this issue.”

Ironically, in his opposition to Dunn’s 2021 state Supreme Court petition, Assistant Attorney General Crane cited Senate Bill 53 as a reason the court should deny Dunn’s habeas corpus petition—an arguably cynical maneuver, given the reflexive opposition of the attorney general’s office to the work of conviction integrity units. Gardner told me that she plans to take on Dunn’s case, but Dunn has little faith in a favorable outcome. “Senate Bill 53 doesn’t say anything about a claim of actual innocence, so they can still bypass us,” he said.

Still, compared to Potosi, which, during Dunn’s time there, housed almost exclusively death-row and life-without-parole inmates, life at South Central Correctional gives him hope. He is now a kind of elder statesman; younger inmates, many of them from North St. Louis, call him Uncle, or Unc. And at least once a week, “You see somebody going home. Even though it’s not you, you see some sense of hope or relief in watching someone else get what you think you deserve.”

Dunn described the plans he and Kira had for the day of his release. In advance, she would send him an outfit of his choosing. “I’d prefer to have a suit, but they don’t have no tailor in here,” he said. “I would walk up that long little driveway until I’m off the property. That’s my way of trying to walk out of prison for everybody else who can’t walk out themselves.” They would gather at a restaurant for a meal with Dunn’s family. “We gonna go there, enjoy ourselves, take a few pictures, then we getting out of Missouri the first thing smoking.” They would drive through Texas, where Dunn has family, and on to California.

Perhaps, before leaving Missouri, just once, he would visit the graves of family members: his father; his half sister, Valerie; his nephews, Raymond and Nathan. “I never even got a chance to hug them two kids. I thought I was gonna make it out of prison before they died.” But the community that fills his memory no longer exists. “If you look at my old street, there’s nothing on that street no more. Forty-three houses sat on that street. There’s not one.”

A few weeks before meeting Dunn, I’d driven with Arnetta and Kira to the neighborhood where Dunn and his siblings grew up. When the family home burned down, in 2012, it was one of only two houses left on the block. This area of Wells-Goodfellow today is scarred by rows of vacant homes; discarded furniture and the occasional stripped car litter the alleys. One can travel for blocks at midday and see no movement. Much evidently abandoned North St. Louis property has been repossessed by the city. Private developers have scooped up other tracts.

Walter Johnson, a Harvard historian and the author of the proudly intemperate St. Louis history, The Broken Heart of America, argues that much of the city’s development has been fueled by the forceful, exploitative relocation of Black residents—from Downtown to neglected projects, from the projects to under-resourced neighborhoods in Northwest St. Louis, and finally, to the state’s rural prisons. “What’s happening now is extraction on the basis of people’s poverty,” Johnson told me. “Black people and the criminalization of Black people have become a public-private resource for Missouri.”

Kira parked her rental at the corner of Ashland and Belt, where the Dunn home stood, and we got out of the car to walk the block. The day was bright but frigid, and Arnetta was bundled in a white coat and orange scarf. She pointed to a hardy bush her mother had planted, and to the remains of a neighbor’s shed where she and her siblings used to play. Her mother’s attachment to the old house, Arnetta said, may have distracted her from the deterioration of her surroundings. “She looked at it like, she and my daddy got that house and raised their kids in it.” Before the lot was cleared, Arnetta collected several of the original bricks. One is reserved for Kira, and she and Dunn plan to use it in a home they hope to build.

Dunn knows, though, that he may never leave prison. He has devoted many hours to writing an autobiography. It contains things that he has never told his mother or sisters—memories of his father and of his murdered half-brother Lil’ June, his efforts to become a better husband and son. In a letter, he had told me that he wrote it in part out of a “fear of dying without my family knowing who I was.” At South Central Correctional, I asked what he meant. “Just because they put me in prison don’t mean I’m dead,” he said.” I want my sisters and nephews to know that I’m nothing what the state said I was. I’m more to it.” He went on, “When I leave this world, I want people to say, ‘Well, OK, he was in prison. But he still lived.’”

This article was supported by the journalism nonprofit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.