The El Hiblu 1 appeared as a red dot on the horizon, navigating the brackish Mediterranean swells after sunrise. It was March 26, 2019. Kader and 107 other migrants and refugees departing from Libya had been at sea for at least 19 hours in a dinghy designed to hold 15 people at most. It was losing air. Some had thought about jumping and swimming but realized no option would lead them to safety. Through the previous night, women clutched crying children. Everybody prayed. Kader, who was then 16, recalled thinking, “There is no chance for us.”

The sight of the El Hiblu thus brought relief, but the situation was also worrying. The oil tanker, which was named after its fortysomething-year-old Libyan captain, Nader el-Hiblu, had been sent the coordinates of the dinghy by an airplane circling overhead earlier that morning. The plane was part of Operation Sophia, a European Union mission to combat smuggling and rescue refugees and migrants at sea. There was no guarantee the dinghy’s occupants would be taken to European waters, but as the El Hiblu pulled alongside it, the choice was simple: Board the boat or risk drowning. Six men, distrusting the Hiblu crew’s promises not to return them to Libya, remained in the dinghy. Their fate today remains unclear.

As for those who boarded the El Hiblu, their journey at sea was just beginning, and the extraordinary details of what happened aboard the ship would be debated to this day. But this much is certain: The journey would end in the tiny island nation of Malta, with Kader and two other teenagers jailed on terrorism charges.

In some ways, the case of the El Hiblu is a classic one: Refugees and migrants from Africa seek safety and economic opportunity in Europe and instead discover a Europe that has become increasingly inhospitable to people fleeing hardship and violence. Their ordeal epitomizes the “failures of European authorities to take care of what happens in the central Mediterranean in a way that is in line with international standards and their obligations,” Elisa de Pieri, a researcher at Amnesty International, told me last autumn. “This case is a sort of condensed version of everything bad that happens along this route.”

But the case is also unusual in troubling ways: Never before, according to legal experts, have migrants and refugees faced terrorism charges for rescuing themselves, while also being accused of commandeering a ship. And today, after three years, their trial plods along with a hearing roughly every month, with just one witness called to the stand each time. The Maltese prosecutors, along with the government, arresting officers, and courts refused to comment on this story as the case is ongoing. It’s unclear when, or how, the trial might end.

Kader has thus traded one terrifying limbo for another: Imprisoned in Libya, he and two others are now trapped in legal purgatory in Malta.

Kader left Ivory Coast more than four years ago—he doesn’t recall exactly when. It took months to get to the Libyan capital of Tripoli, where, he said, he was imprisoned in a pay-for-release scheme. One day, after several weeks, he was handed off with another migrant to a man who drove them out of Tripoli.

They asked the man where he was taking them. They were told not to worry. As they drove farther from the city, Kader considered jumping, but the car was moving too fast. He needed the work and hoped the man was honest, Kader told me recently. He was put to work on a farm, fed very little, and never paid. He worked at gunpoint. Then the man transferred Kader to work another farmer’s field. He would not be paid again, but his involuntary work would help pave the way toward a new life in Europe.

One night, the man unlocked the room in which Kader was kept and told him he’d set out from Libya that day. He put Kader in a big truck with other migrants and refugees and drove them toward the sea. A large rubber boat sat at the water’s edge. “Some people … they don’t want to get in the rubber boat … even me,” Kader told me. “You see the rubber boat, and you see the sea … you don’t want to go. Even if you paid.”

/ In honor of Earth Day, TNR’s climate coverage is free to registered users until April 29. Start reading now.

Kader sat aboard the dinghy as it was pushed off from shore. The tubular boat crested waves farther north into the sea in which an average of six people would die or go missing each day in 2018 as hundreds of thousands of migrants sought refuge from war, food insecurity, and authoritarian governments in the last decade. The central Mediterranean crossing was also the deadliest: That year, 2,275 people had died trying to cross the sea.

The next morning, their dinghy losing air, the migrants heard the distant buzz of the Operation Sophia airplane. The airplane radioed the El Hiblu.

“Sir, there are lives at sea, can you assist them?”

“OK, no problem. What assistance do you need?”

According to the refugees, when the El Hiblu reached the dinghy, the captain told them—through a teenager from Guinea, Amara, who spoke English and who fast became friends with Kader and another teenager, Abdalla—that he would wait for international rescue boats to take them north, to Europe. So that night, the refugees spread out across the deck to find some rest, only to awaken to the sight of the Libyan coastline. People began crying and shouting.

What happened next is in dispute.

According to Kader, the captain, el-Hiblu, told the teenagers who translated for the migrants and refugees that he had gone to the rendezvous point to meet with an international NGO, but no one was there when they arrived, so he decided to head to his port of destination. (A vessel for Sea-Eye, a sea rescue nonprofit based in Germany, was in the central Mediterranean, but the organization told me it was too far to reach them.) Kader, along with the two other boys, recalled el-Hiblu pulling out a map and pointing to Malta, letting them know it was a European country and that he had enough fuel to take them there. He told the young boys to stay on the boat’s bridge and to tell the passengers everything was fine. The captain ordered them to calm the passengers by telling them they were destined for Europe. Some did not believe the captain a second time. Yet the boat turned and headed north.

El-Hiblu and his crew told different stories during their court testimonies: that the migrants had wielded tools found on the deck in anger and frustration; or that none of that happened. The captain feared for his life during the “horror” of what seemed to be a near-revolt of around two dozen passengers, he later recalled in an interview with the Associated Press. He told the wire service he was forced to lock himself and the crew in the bridge overlooking the ship: “They attacked the cockpit, heavily beating on the doors and the windows, and they threatened to smash the boat. They went nuts, and they were screaming and shouting: ‘Go back! Go back! Go back!’”

What’s not in dispute is that Maltese special forces on two speedboats, supported by a patrol vessel and helicopter, boarded the El Hiblu on May 28. The special forces saw no evidence of a struggle, according to witnesses. The tanker was escorted to the Maltese city of Senglea, across a strip of water from the old city of Valletta and its throngs of tourists. Kader, Amara, and Abdalla were arrested and eventually taken to jail. They were later indicted on 10 counts, including unlawfully seizing control of a vessel.

The boys now face decades in prison.

I arrived in Malta in October. Just outside the airport, south of Senglea, stood a raised platform where a few people watched planes take off and land. Behind that was the Safi Detention Centre, a military base used to house at least 200 refugees and migrants—one that Dunja Mijatović, the Council of Europe’s commissioner for human rights, visited not long before my arrival. She found the conditions of block A deplorable and undignified, and in a public statement called on authorities to “focus on investing in alternatives to detention.”

Malta, which joined the EU along with nine other countries in 2004, is the bloc’s southernmost nation state and therefore on the front lines of the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean. At just 122 square miles and with 516,100 people, Malta also has one of the highest number of refugees per capita in the EU. It is perhaps no surprise that the country has long embraced restrictive immigration policies.

But in recent years, Malta has further tightened its stance. It has stopped permitting humanitarian groups to launch rescue missions from its shores, Sea-Eye alleges, and the country has refused to allow rescue ships carrying migrants to dock at its shores unless other member states agree to take responsibility for some of the migrants and refugees. An Amnesty International report in 2020 accused Malta of “ever more despicable and illegal tactics,” including pushing back migrants (sometimes at gunpoint, allegedly), detaining them on offshore quarantine ferries, and working closely with Libyan authorities to keep migrants from taking to the sea in the first place.

In a way, Malta has been an indicator of a shift in sentiment across Europe, amid a rise of far-right and nationalist political parties, about how to treat migrants. Blocking entry to migrants and returning them to places of hardship has become the de facto response. European countries have all but shuttered rescue programs, like the operation that first identified the El Hiblu, in favor of specialized technology: Automated text messages are sent to people who attempt to enter Poland from Belarus; A.I. lie detectors are used to scan the faces of asylum-seekers as they’re interviewed in Hungary, Greece, and Latvia; the 162-decibel blasts of sound cannons are fired at refugees entering Greece from Turkey; and surveillance drones search for migrants in Malta, Croatia, Italy, and Austria. The system is dubbed “Fortress Europe.”

“Maybe what we’ve seen in the past few years is a more aggressive approach toward the ‘We don’t want any migrants’ policy,” said Neil Falzon, the defense attorney for Kader, Amara, and Abdalla. “It’s getting worse.”

And yet this heightened animosity toward migrants has not had the desired effect of deterring them: In 2021, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees says 123,318 migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers arrived in Europe through the Mediterranean—a virtual return to the numbers reported before the coronavirus pandemic shuttered borders globally and offered a scapegoat to increased hostility. At least 1,977 died or went missing.

The case of the El Hiblu 3, as the young men are now known, could have far-reaching effects on other migrants, advocates and researchers say: If they’re found guilty, private vessels will be less likely to help stranded people at sea for fear of being prosecuted themselves—as in the case of Claus-Peter Reisch, the captain of a Dutch vessel with Mission Lifeline, a nongovernmental organization active in migrant rescues. In 2018, the boat was held at sea for a week after rescuing 234 migrants. Malta eventually allowed its entry into port, only to confiscate the boat and charge the captain.

“Although the norms are sometimes clear, it’s not clear who they apply to,” said Erik Røsæg, who teaches at the Department of Private Law at the University of Oslo. “I think the new thing is that the same acts that were thought earlier as being acts of passion and helping migrants in need, they are now criminalized.”

Meanwhile, migrants in Malta, which has come to rely on them for labor, can face brutal work conditions. During my visit, the name Jaiteh Lamin often came up. A 32-year-old migrant from Gambia, Jaiteh fell two stories from a construction site where he was working without a permit. He was seriously injured. In an attempt to cover up the accident, Jaiteh’s boss, a local contractor, took him to a rural road and left him. A passerby found him crying for help and saying that he thought he was going to die.

“It’s very common for that to happen, and that is just one episode that hit the news,” said Falzon, who is assisting Kader with a work-related claim. (Kader’s bosses demanded money in exchange for a door he broke. He subsequently quit his job and was threatened with legal action if he didn’t replace the door.) “But we know of many cases of migrants hurt at work, and they’re dumped in the streets, and they’re told by the employer not to disclose where they work or the conditions they were working under.”

In other words, it sounds a lot like the life in Libya that the El Hiblu 3 fled.

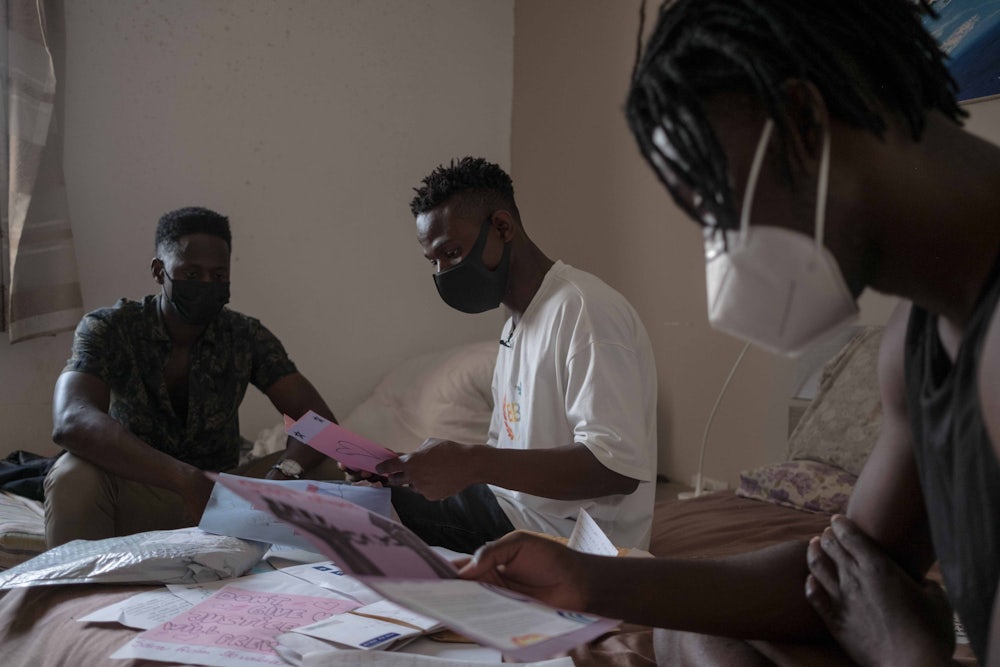

The El Hiblu 3 have settled into European life, to the extent they can. Amara, now 18, obsesses over professional soccer and dreams of moving to Canada. Kader, 19, loves watching Manchester United and reading. Abdalla, 22, now has an 8-month-old girl. Over the last year, they have received thousands of letters from supporters as their case drags on in a Maltese court. They read the letters together each Sunday.

But the case against them is never far from their minds. They’re required to check in at the local police station and once monthly with their probation officers, as well as regularly attend court for hearings and legal motions or arguments. In February, a witness testified in court that the three teenagers instilled calm among the passengers and were not seen to be wielding weapons or tools. A new date was scheduled on the docket and the court adjourned.

“I cannot say that I’m happy. I’m not happy, because it’s like, half of me in prison and half of me outside,” Kader said. “One day, they can take me back to prison.”

Kader often reflects on the events of March 26, 2019, and what came after. The captain, he says, ordered the boys for tea and cookies in the cabin, then attempted to convince the boys to say they had seized control of the boat. As the tanker approached Maltese waters, el-Hiblu pleaded with Amara to take the radio and tell Maltese authorities they would kill everyone on board if they weren’t rescued. El-Hiblu implied this was the only way to ensure the migrants would be delivered to European soil.

The captain perhaps knew that if he told the authorities he was carrying migrants, the ship might be held out at sea indefinitely—a reason why many boats no longer save migrants. They aren’t insured for time lost, for oil not delivered or fish spoiled. They are made to choose between their cargo, their livelihood, and souls adrift at sea.

“For the first time I put my leg in European land; the same day they take me to prison,” Kader told me. We were sitting at a café in the Upper Barrakka Gardens as tourists drank beers and snapped panoramic photos of the Port of Valletta. Within view was the wharf at which Kader arrived in 2019. “He lied to us,” he said, referring to el-Hiblu. “He tried to put us into this problem, and to save himself and go.”

Meanwhile, in November, government officials from European nations including France and Italy met to discuss ways to stabilize Libya and deter refugees and migrants from attempting to cross the Mediterranean. The EU has sent more than $565 million to bolster Libyan capabilities, such as equipping and training the Libyan Coast Guard to patrol the sea and intercept migrant boats before they reach European waters but also to support NGOs and partners working in the country. That funding doesn’t always reach its intended payee.

Though the migrant crisis in the EU has not returned to the levels seen in 2015, a steady stream of boats still attempt to cross the Mediterranean. On a single day in November, around the time EU leaders were meeting to discuss Libya, the Italian Coast Guard rescued more than 420 refugees in distress in the sea. On one boat, 75 refugees drowned, north of Libya.

The drownings were reported by survivors who had been rescued by fishermen. They were sent back to Libya.