In the fall of 2020, a story broke on the front page of the Los Angeles Times. It featured a striking image of a barrel sitting on the floor of the ocean, emitting an eerie, phosphorescent glow. Over the past decade, the story explained, scientists had discovered thousands of barrels of acid sludge, a by-product of the manufacturing process for the notorious pesticide DDT, sunk off the coast of California. Enormous quantities of DDT waste had seeped out of the barrels and into the surrounding environment. It remained unclear, however, how much DDT was down there or how exactly—and even whether—any remediation efforts might be undertaken. “At this point,” writes the historian of science Elena Conis, “only one thing is clear: seventy-five years after scientists first warned of its hazards, sixty years after Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring, and fifty years after it was banned, DDT is still here.”

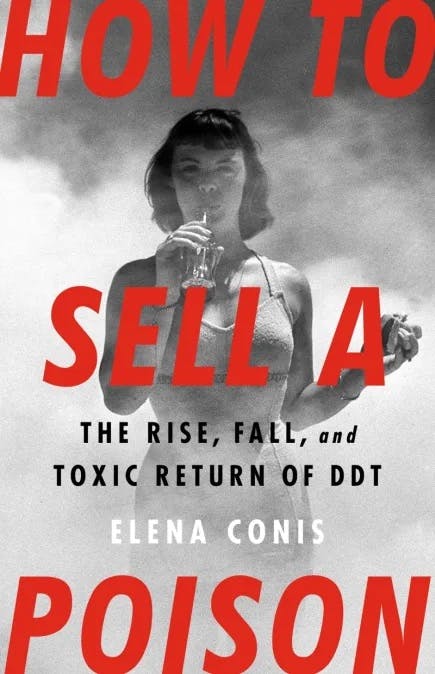

Indeed, as Conis details in her monumental—and monumentally disturbing—new book, How to Sell a Poison: The Rise, Fall, and Toxic Return of DDT, DDT remains in our soil, our water, the animals that surround us, and even within our very bodies. Yet the story of this infamous pesticide has long been incomplete. If you ask Americans to state what they know about DDT, most would probably describe the pesticide’s ubiquity before the ascendant environmental movement—led by Rachel Carson—forced the government to eliminate it. This story, while not exactly wrong, overlooks much of the complexity (and complicity) in DDT’s biography, including the numerous recent calls to bring the pesticide back into use again.

A former features writer and health columnist for the Los Angeles Times, Conis is probably best known for her book Vaccine Nation: America’s Changing Relationship With Immunization, which probed the histories of vaccine policy and vaccine hesitancy years before the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic. She now teaches journalism, public health, and history at the University of California, Berkeley, making her perhaps uniquely qualified to recount this complicated story.

For years, Conis writes, she taught her students the familiar three-act story of DDT: First, it was a hero, sprayed all across the United States with abandon; then, it was a pariah, denounced by Rachel Carson and quickly banned by the federal government; but then, it experienced an unlikely popular resurgence, as many demanded that the ban be lifted, acknowledging DDT’s toxicity yet claiming it was needed to fight malaria. “But the third act always nagged at me,” Conis writes. “Why was the late 1990s the moment when Americans started calling for DDT’s return?”

After years of research and archival digging, Conis arrived at what she calls an “unexpected answer”: the tobacco industry. For truly, was there ever any group better qualified to sell a poison?

World War II was raging in Europe when an employee of the Swiss chemical giant J.R. Geigy discovered that dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, an obscure chemical first synthesized decades earlier, was startlingly good at killing the Colorado potato beetle. Although this discovery reportedly prevented a famine in Switzerland, few on this side of the Atlantic felt it was terribly important—the American potato crop was robust enough—until the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and suddenly the U.S. was at war. Desperate to stop the spread of malaria, typhus, and other insect-borne illnesses among troops, the American military began testing the flavorless, colorless chemical in the lab and on human subjects. (The German government, to which neutral Switzerland had also offered the chemical, declined out of fears of “the compound’s potential risks to people,” Conis notes.)

What the Americans, and their British allies, soon discovered was stunning. This chemical, its unwieldy name usually shortened to DDT, was marvelously effective at killing all manner of pests; it was long-lasting; and it did not appear to be deadly to bigger animals. Allied government officials, concerned about DDT’s potential risks to humans, had decided to test the chemical in a refugee camp in Naples, Italy, dousing more than a million civilians in just two months. Amazingly, a feared typhus epidemic never materialized, and the scientists could discern no harm to people. And while a U.S. government study showed that large doses of DDT were harmful in smaller animals, this was wartime. So when U.S. Marines invaded Saipan and encountered armies of disease-carrying insects, fighter jets sprayed DDT across every inch of the Pacific island and kept the dreaded diseases at bay. DDT ended World War II as a war hero, and newspapers hailed it as a “miracle.”

Earlier pesticides had often been too poisonously effective, and their residues could and did sicken and even kill humans. Not DDT, or so it seemed. In August 1945, the U.S. government released DDT for sale to the public, blandly warning consumers not to use too much or else they might “upset the balance of nature.” Yet DDT was so easy to manufacture that soon it was everywhere.

DDT was a superchemical in an age of miracle drugs and magic bullets, of penicillin and sulfonamides. So, just as midcentury doctors were excitedly prescribing the wonder drugs in such quantities that we are still dealing with the resulting rise of antibiotic resistance, midcentury farmers coated their fields and orchards and even livestock in astonishing quantities of DDT. The pesticide was injected into walls and wallpaper, mattresses and clothing. Housewives used DDT to wipe out annoying pests, dousing their own pets with the stuff to kill fleas. Amid an increasing polio epidemic and fears that flies might spread the condition, cities across the U.S. drenched themselves in DDT. Even after scientific studies revealed that DDT “simply did not combat polio,” officials and communities continued to demand its spew. “City officials sent out cavalcades of DDT spray trucks to clear neighborhood streets of insects, and children ran behind them, playing in the mist,” Conis writes. And it wasn’t just DDT: In the years after the war, nearly a thousand new chemical pesticides flooded the American market.

In the midst of such widespread pesticide usage, a few rumblings of concern arose: a woman dying after eating blackberries that had just been sprayed; a tenant farmer collapsing in a sprayed tobacco field; a group of war prisoners mistaking DDT for flour and feeling weak for months; cows across the country dying en masse due to a mysterious “X disease”; humans (including Bing Crosby and Errol Flynn) being diagnosed with “virus X” after suffering joint pain, muscle weakness, fatigue, and severe headaches. A few individuals spoke up in protest of the pesticides, including Marjorie “Hiddy” Spock, an educator (and sister of the famous physician Benjamin Spock) who, in the late 1950s, sued the federal government to try to stop the spraying of DDT on her Long Island home. Still, the spraying continued.

Spock, however, had connections, and soon she was in touch with a popular science writer named Rachel Carson. Spock’s own research and trial transcripts proved to be a key source for Carson, who ultimately published Silent Spring, her famous and influential book, in 1962. Silent Spring charged the indiscriminate use of pesticides (especially DDT) with causing cancer and other illnesses in humans and nonhuman animals alike. (Carson, herself, was soon dead from breast cancer.) The book met with many savage reviews, some the product of chemical industry machinations, and the agriculture secretary himself denounced Carson as a spinster and a Communist, but Silent Spring shone a spotlight on DDT like nothing before.

The book’s publication dovetailed with the rise of a massive, grassroots environmental movement, and it has rightly been credited with contributing to this ascent. Conis takes care to emphasize, however, that Silent Spring did not emerge in a vacuum, and others had been fighting independently for the environment—and against chemical pesticides—for years, including Mexican and Mexican-American farmworkers in California’s Central Valley. Indeed, it was a boycott spearheaded by the United Farm Workers that led California to ban DDT on grapes and dozens of other crops in 1970, which created a precedent on which the newly founded Environmental Protection Agency drew when it banned DDT nationally in 1972. Marches, protests, teach-ins, and lawsuits filed all across the nation zeroed in on DDT, making the federal government’s response seem virtually foreordained.

But alongside activists and political movements, DDT had a surprising opponent in big business. For years, the tobacco industry had been a heavy user of DDT, which it employed to protect tobacco crops from damaging pests. But it had become clear to Big Tobacco that it was in the companies’ best interest just to get rid of DDT. Countries in Europe were phasing out DDT much more aggressively than the U.S.; if American tobacco companies wanted to sell their products there, they “needed to get DDT out of U.S. tobacco.” They also realized they could use DDT as the scapegoat for the variety of health concerns around smoking: When the industry’s internal research revealed the presence of DDT in cigarettes, cigarette smoke, and smokers’ bodies, executives decided they could spin these studies to make it seem like the health risks of smoking were the result of carcinogenic pesticides rather than the cigarettes themselves.

The bigger chemical companies too were broadly fine with DDT’s downfall. Even though they had once sold large quantities, they did not have much to lose. No company held a patent to DDT, which was in the public domain after its wartime development, meaning none of the big players were able to exploit it effectively for profit. In fact, a ban would create a new opportunity to profit. With DDT off the market, it would be easier for chemical companies to sell their own “pricier, patented pesticides.” And so it was that a ban on one of the most famous and (for a long time) popular consumer products in twentieth-century America served the interests of capital.

The irony is that, at the time of DDT’s ban, the science linking its spray to human health was suggestive but inconclusive. Even environmentalists acknowledged that the health risks of pesticides could not be measured in the same way that the risks of cigarettes had been. The tobacco studies had compared smokers with nonsmokers; because DDT was in every American’s body, similar studies of its effects were impossible.

Yet in the decades that followed, various scientific findings gradually accumulated into a critical mass. As Conis details at length (perhaps a bit too much length), we now know that DDT causes tumors in mice and rats; it thins bird eggs to the point that mothers inadvertently crush their gestating offspring; it may disrupt birds’ sense of orientation, sending them out to sea to die; it fundamentally alters the reproductive organs of an array of critters; it can poison animals even decades after spraying has ended. Further, a growing body of evidence has linked DDT to numerous forms of cancer in humans—especially breast cancer. Studies have shown how the levels of DDT in our bodies track inequalities in human society; for instance, there are higher DDT levels in Black people than in whites and higher levels in poor people than in rich ones.

One of Conis’s greatest achievements is to put a human face on this science of risk. Among her most intriguing case studies is the Alabama town of Triana, where the predominantly poor and Black inhabitants were exposed to quantities of DDT unmatched in the scientific literature. For years, a nearby manufacturing plant had leached chemical residues into the town’s water, and by the time the federal government began testing, experts learned that Triana’s riverside residents were regularly eating fish with DDT levels 50 to 90 times higher than what the FDA considered safe. One 83-year-old in Triana had four times more DDT in his body than had ever been recorded in another human. Yet for years after this discovery, experts debated whether all of this DDT posed any significant health risk to the residents at all. And, as this debate raged on, the DDT levels only continued to rise. “This used to be a lively little town,” declared one local grocer, quoted by Conis. “But this problem has changed everyone’s attitude. We’re like prisoners on death row, just waiting to die.” Eventually, the residents of Triana sued the Olin Chemical Company, ultimately wresting a $24 million settlement from the behemoth.

Perversely, however, even as cleanup efforts were beginning in Triana, and even as scientific evidence of the harmfulness of DDT was accumulating, calls to bring it back were increasing in volume. Many of the pesticide’s champions noted how DDT had almost entirely eliminated malaria deaths in the U.S. half a century before and how, in the 1940s and 1950s, widespread spraying of DDT drove malaria rates “to previously unimaginable lows” in countries across the global south. Even in the 1960s, as disturbing scientific findings were emerging, some scientists insisted that DDT was saving far more lives than it was endangering. But the pesticide’s broad elimination in the 1970s (coupled with increasing opposition to the heavy-handed, colonial tactics of the World Health Organization) had sharply scaled back DDT spraying. Malaria rates began to climb again in many poor countries. And so, in the 1990s, a great many scientists started calling for more DDT spraying.

This coincided with the loosening of the laws governing pesticides in the U.S., as well as outbreaks of West Nile virus that led New York City officials to douse the city’s boroughs repeatedly with chemical pesticides. Conservative think tanks published reports comparing indeterminate studies of DDT’s harms to the millions of malaria deaths across the global south. Less partisan actors noted that organochlorine pesticides like DDT had only been replaced by organophosphate pesticides, which are far deadlier than their more famous cousins. And many framed the calls for the resumption of DDT spraying within the fashionable language of cost-benefit analysis. Responding to DDT’s possible link to lower infant cognition, one scientist remarked, “I’d rather have a child with three IQ points less than have a dead child.”

Ultimately, the campaign to bring back DDT found limited success. When more than a hundred countries, initially meeting under the aegis of the United Nations, negotiated a treaty to phase out persistent organic pollutants, including pesticides, their final treaty created an exception for DDT. Today, DDT is used to combat malaria in sub-Saharan Africa, and it remains cheap and effective—but it is also rare, manufactured by just one company in India.

Conis recounts DDT’s enigmatic third act with aplomb, but her greatest feat is to reveal the role played by Big Tobacco and its allies within industry and associated think tanks. The tobacco industry had cultivated its own scientific experts, sponsored its own medical research, and hired Hill & Knowlton, a savvy public relations firm, to inundate journalists with the industry’s own “facts.” Cigarette companies financed armies of letter and op-ed writers, think tank reports, and “expert” testimony promoting the return of DDT. They sought to use the fight over the pesticide to amplify the threat of malaria and imply a hypocrisy in Western-led global health efforts. And they did all of this in secret.

Big Tobacco fought for the return of DDT, Conis argues, because the pesticide made for such “a helpful scientific parable, one that, told just right, illustrated the problem of government regulation of private industry gone wrong.” It was private companies, and not politicians—or, heaven forfend, the people—who should decide what products should be produced, and how. DDT also served as both a useful distraction and a powerful cudgel for an industry trying desperately to discredit the increasing science demonstrating the dangers of secondhand smoke. “To sell one poison,” Conis comments dryly, “the tobacco industry sold a morality tale about another.”

Big Tobacco makes for an extremely satisfying villain. Yet at times Conis may overstate, or at least oversimplify, the role of Big Tobacco. It’s unclear how much say the industry had in the 1972 DDT ban. “Everyone in the tobacco industry,” Conis writes, “had decided that it was time to be done with DDT,” yet this stays mostly at the level of provocative implication. It is clear Big Tobacco had accepted—and even found ways to exploit—DDT’s death knell, but did the cigarette makers play any particular part in the pesticide’s demise? Conis notes in passing that the cigarette giant Philip Morris urged its tobacco dealers to lobby government regulators to curb the use of persistent pesticides—“especially DDT”—but goes no further.

And while Big Tobacco’s role in financing the calls for DDT’s return is clearer, by pinning so much of the blame on the tobacco industry and its allies, How to Sell a Poison undersells the much broader neoliberal turn in the 1990s, and risks letting the casually reactionary grassroots off the hook. At this time, people and groups across the political spectrum were advocating policies that sought to replace state functions with the private market; to end the era of big government (with its attendant regulation) and return to an idealized simpler time (read: no red tape). Public officials at all levels hastened to cut budgets, privatize services, and rely more and more on unaccountable (supposedly nimbler) corporate actors. This philosophy and approach meshed perfectly with the calls for DDT’s return, allowing individuals with megaphones to portray themselves as iconoclasts and smack down the lumbering government and its misplaced zeal to save the spotted owl. The case of DDT was indeed the perfect metaphor, but not just for Big Tobacco—it emblematized an entire age and its dominant political movement.

All of this is meant only as a light criticism of Conis’s work. In fact, the exact role of capital and prominent capitalists in the histories of DDT and scientific obfuscation is undoubtedly difficult to discern, in large part because so many corporate archives remain shuttered to neutral academics. And Conis brilliantly tracks the complicity that can be rightly foisted onto her primary antagonists. As she notes, the tobacco industry–funded talking points easily infiltrated the broader discourse in the 1990s. “It’s time to spray DDT,” argued Nicholas Kristof in a piece on combating malaria. Another New York Times editorialist, Tina Rosenberg, charged Silent Spring with “killing African children.” Bloggers called Rachel Carson a bigger mass murderer than Hitler. Of course, none of this would have been possible if the neoliberal framework had not already been in place, but the story is incomplete if we overlook the dark machinations of a handful of corporations.

Much to her credit, Conis does not end her book with some pat lesson or underdeveloped call to arms. She states only that perhaps this history might lead us to accept that “science is social,” that it is the product of human beings, that it is an ongoing process and not gospel. Frighteningly, precisely because science is a sometimes slow and necessarily iterative process, it’s likely we will never see a ban of a poison on this scale again. The story of DDT is a complex one, but it is not a “morality tale”—rather, it is “an illustration” of what happens when we unleash vast quantities of pollutants into the environment and only try to regulate them later.