If you’re charged with a serious crime and you can’t afford a lawyer, the government has to provide you with one. (That is, for now.) There are about 1.5 million lawyers in the United States. Many of them are good at their jobs. But some of them aren’t, for various reasons. Maybe they’re overworked and juggling too many cases. Maybe they don’t have the resources they need to vigorously advocate for their clients. Maybe they’re out of their depth on a particular case. Maybe they just aren’t cut out for their current line of work.

David Martinez Ramirez and Barry Lee Jones, two Arizona death-row prisoners, think that their respective lawyers did a bad job of defending them. (Their cases are unrelated, except for this particular legal issue.) The two men told the Supreme Court last year that they were harmed by “ineffective assistance of counsel,” as the courts call it, at two separate stages: first, by their trial lawyers not representing them well in front of a jury and then, again, by their state appellate lawyers not properly challenging their convictions because of their trial lawyers’ allegedly shoddy work. They wanted a new trial to fix the problem.

When you think your constitutional rights were violated by a state court, you can theoretically challenge your conviction in the federal courts. The Sixth Amendment protects the right to legal counsel, and the courts have logically interpreted this as the right to effective legal counsel because otherwise, the right to an attorney wouldn’t be worth the parchment on which it was printed. Ramirez and Jones now have federal appellate lawyers—and effective ones, to boot—who asked a federal district court to overturn their clients’ respective convictions because their previous lawyers weren’t good enough at their jobs. Since the two men are on death row, the stakes are as high as they get.

On Monday, the Supreme Court said no. The court, in a 6–3 decision that fell along the usual ideological lines, ruled that the two men couldn’t introduce new evidence that their previous lawyers were ineffective when asking the federal courts to intervene. The decision is a chilling reminder that the court’s conservative majority need not overturn a constitutional right, as it will in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, to destroy it—the justices can simply pare it back into oblivion.

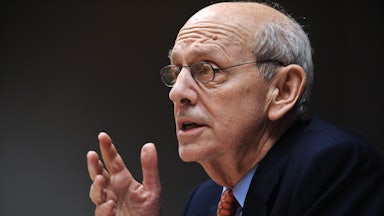

“This decision is perverse,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in dissent, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan. “It is illogical: It makes no sense to excuse a habeas petitioner’s counsel’s failure to raise a claim altogether because of ineffective assistance in post-conviction proceedings … but to fault the same petitioner for that post-conviction counsel’s failure to develop evidence in support of the trial-ineffectiveness claim.”

An Arizona jury convicted Jones of the murder of his girlfriend’s four-year-old daughter. Prosecutors argued that her fatal injuries occurred while she was in Jones’s custody; Jones’s lawyer failed to introduce “readily available medical evidence that could have shown that Rachel sustained her injuries when she was not in Jones’ care,” Sotomayor noted in her dissent. The Intercept’s Liliana Segura has also reported on serious flaws in the prosecution’s case—and, just as troublingly, glaring oversights by Jones’s defense during his trial that could have affected his conviction.

Ramirez was convicted of murdering his girlfriend and daughter and received a death sentence. During the sentencing phase in capital trials, lawyers from both sides present mitigating and aggravating evidence for the jury to consider when passing its sentence. Ramirez said that his trial lawyers failed to build evidence about his intellectual disabilities, including his mother’s history of drinking when pregnant with him, evidence of her abuse toward him as a young child, and his signs of developmental delays. On appeal, Ramirez’s lawyer admitted in an affidavit that she was not prepared enough to handle “the representation of someone as mentally disturbed” as him.

In theory, these ineffective-assistance claims could be resolved on appeal by better lawyers. But indigent defendants are all too often represented by ineffective lawyers during their state appeals, as well, compounding the constitutional problems. These shortcomings are clear enough that the Supreme Court sided with defendants on the issue in the 2012 decision Martinez v. Ryan and then in the 2013 decision Trevino v. Thaler. In those decisions, the justices allowed federal courts to hear ineffective-counsel claims from the trial phase even if the defendant’s state appeals lawyer (also ineffectively) failed to preserve that claim on appeal. One bad turn, in other words, did not deserve another.

Monday’s ruling clawed back those protections without overturning them. One problem with having an ineffective lawyer during state appeals is that they might not develop evidence of ineffective assistance by their trial court predecessor. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, ruling in both Jones’s case and Ramirez’s case, held that federal courts could hold evidentiary hearings so that the two men could prove their cases. In his majority opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas said that these hearings weren’t allowed.

“In our dual-sovereign system, federal courts must afford unwavering respect to the centrality of the trial of a criminal case in state court,” he claimed, paraphrasing from past Supreme Court decisions. It is there, Thomas argued, that evidence should be presented, even if the defendant is assigned an incompetent lawyer. “Such intervention is also an affront to the State and its citizens who returned a verdict of guilt after considering the evidence before them,” he went on to add. “Federal courts, years later, lack the competence and authority to relitigate a State’s criminal case.”

Thomas even complained that the federal court had held a seven-day hearing in Jones’s case where it heard from 10 witnesses, all of whom cast serious doubt on the validity of Jones’s conviction. “Of these witnesses, only one of the forensic pathologists and the lead detective testified at the original trial,” Thomas noted. “The remainder testified on virtually every disputed issue in the case, including the timing of Rachel Gray’s injuries and her cause of death. This wholesale relitigation of Jones’ guilt is plainly not what Martinez envisioned.” A layperson who hears of this might reasonably think that the problem here isn’t really with the evidentiary hearing itself.

This is a perennial theme in death-row cases before these justices, where abstract interests like the finality of state convictions, the economy of judicial resources, and respect for state-federal relations are prioritized over the real substance of a defendant’s constitutional rights. Typically, in our system it is the people who have rights, while the government has only powers that are bound by them. But in the Roberts court’s imagination, the states have the right to execute death-row prisoners, and all these pesky attempts by death-penalty abolitionists and capital defense lawyers to stop them from carrying out executions are just an infringement of that right.

Sotomayor argued that, as a consequence of Monday’s ruling, indigent defendants in these circumstances in states like Arizona won’t be able to develop the factual record necessary to seek Sixth Amendment relief. “For the subset of these petitioners who receive ineffective assistance both at trial and in state post-conviction proceedings, the Sixth Amendment’s guarantee is now an empty one,” she wrote. “Many, if not most, individuals in this position will have no recourse and no opportunity for relief. The responsibility for this devastating outcome lies not with Congress, but with this Court.”

As I’ve noted before, this roster of Supreme Court justices appears committed to letting executions go forward in almost every circumstance imaginable. Principles that are cherished in other contexts, most notably religious freedom, are set aside so that states can administer lethal injections to their citizens. The justices’ enmity toward death-row prisoners and their lawyers is a breeding ground for constitutional violations—and if Monday’s ruling for Jones in particular is any indication, the possibility that they will sanction the execution of someone who might be actually innocent of their crimes.