Capital punishment holds a strange and unique place in the Supreme Court’s work. Ever since the justices effectively abolished it in 1972 and then resurrected it in 1976, they have taken an unusual level of responsibility for administering the American death penalty. Legislatures still write death penalty statutes, prosecutors still decide when to pursue it, and juries still decide whether to impose it. But it is the Supreme Court that truly decides whether someone actually lives or dies by the government’s hand.

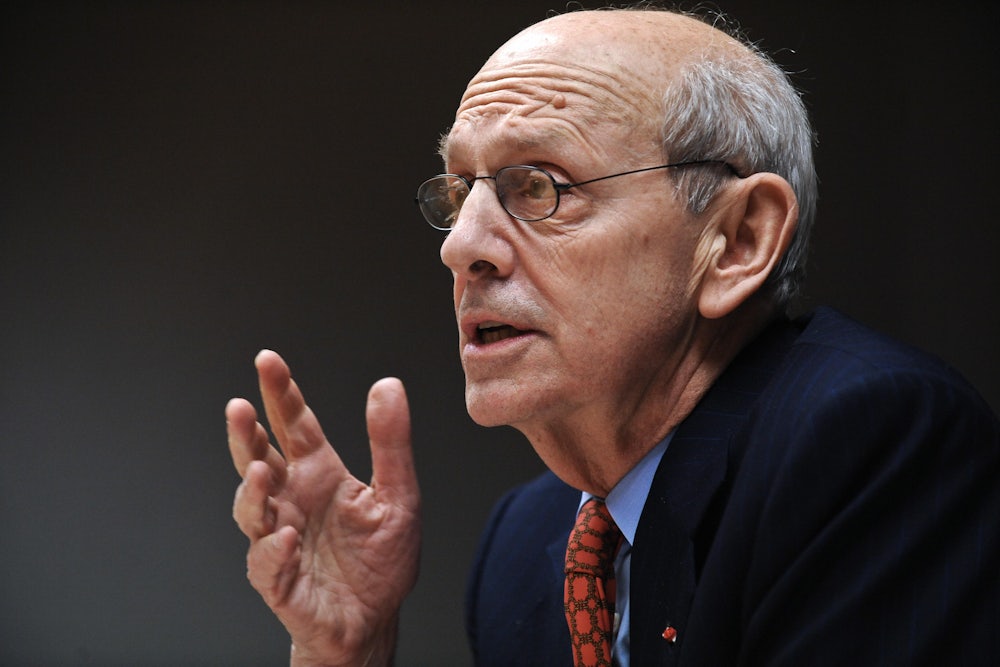

Justice Stephen Breyer, who announced his retirement from the high court this week, did something in 2015 that was both extraordinary and familiar. He urged his colleagues to revisit the constitutionality of American executions, reopening a debate that had disappeared from the court for almost two decades. That he revived what was a moribund question should be remembered as an important, far-sighted part of his legacy.

The case was Glossip v. Gross. Its namesake, Richard Glossip, sued the Oklahoma Department of Corrections in 2014, along with a group of other death-row prisoners, to halt their upcoming executions. At the time, many death penalty states had found themselves unable to secure supplies of sodium thiopental, the traditional sedative used in the traditional three-drug cocktail for lethal injections, after the European Union imposed an embargo on execution drugs. Oklahoma switched to midazolam, a sedative with different chemical properties, which had been rarely used in U.S. executions.

Glossip claimed that the use of midazolam would put him at greater risk for extreme suffering during his execution, which he argued would violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. He had good reason to believe this: Oklahoma had already executed two men while using midazolam over the preceding two years, and in both cases, there were signs that things had gone seriously wrong. Clayton Lockett writhed and convulsed for nearly 45 minutes before dying. Charles Warner’s last words were “my body is on fire”; the state later revealed it had injected him with potassium acetate instead of potassium chloride by accident.

After those botched executions and similar ones in other states, the justices agreed to hear Glossip’s case. The Supreme Court has never held a specific method of execution to be unconstitutional. Until recently, legal challenges to the death penalty focused more on the procedural aspects of death sentences than on how they would be actually carried out. Death penalty abolitionists hoped that a ruling against Oklahoma’s improvised method, combined with the dwindling availability of legal supplies of execution drugs, would effectively halt executions in America.

But the Supreme Court had other plans. During oral arguments in Glossip, Justice Samuel Alito asked why the court should “countenance what amounts to a guerilla war against the death penalty,” referring to activists’ pressure on drug companies. His opinion for the 5–4 majority, later that year, not only sided with Oklahoma but also set a nearly insurmountable threshold for future prisoners to challenge flawed execution methods in the future. Alito’s foundational reasoning was far from strong. “Because it is settled that capital punishment is constitutional, it necessarily follows that there must be a constitutional means of carrying it out,” he surmised.

All four liberal members of the court at the time dissented in strong terms. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote the leading dissent, charging that the majority “leaves [prisoners] exposed to what may well be the chemical equivalent of being burned at the stake.” But the more surprising move came from Breyer. In a separate dissent joined by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, he urged his colleagues to get to the heart of the matter. “Rather than try to patch up the death penalty’s legal wounds one at a time, I would ask for full briefing on a more basic question: whether the death penalty violates the Constitution,” Breyer wrote.

His dissent marked the first time that a sitting Supreme Court justice had denounced the death penalty’s constitutionality in almost 20 years. In the 1972 case Furman v. Georgia, the Supreme Court struck down every capital-sentencing law in the nation, concluding that the sentences they produced were too arbitrary and inconsistent to be constitutional. But four years later, in Gregg v. Georgia, the justices reversed course. The politics of crime had shifted, as had the membership of the court. In a 7–2 ruling, the Supreme Court signed off some of the revised statutes drafted by state legislatures, providing a blueprint for others to follow suit.

The two dissenters, William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall, spent the next 15 years maintaining a lonely vigil against the return of capital punishment. In almost every adverse ruling by the court against a death-row prisoner, the justices would note that they still held that the death penalty violated the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. According to legal historian Evan Mandery, Brennan and Marshall issued 1,841 dissents together until Brennan’s retirement in 1990.

Three of the justices in the Gregg majority later renounced it. When Lewis Powell’s biographer asked him shortly after his retirement if he wished he could change his vote in any case, Powell said he would have voted the other way in every death penalty case. Toward the end of his tenure, Harry Blackmun famously wrote a 9,000-word dissent in an otherwise unremarkable case that declared he would “no longer tinker with the machinery of death.” And John Paul Stevens, the last living member of the court that decided Gregg, said after retiring that he became “disenchanted” with capital punishment after witnessing the court’s mismanagement of it firsthand. In no other area of American law have so many justices publicly denounced their former positions on an issue or case in this way.

Echoing this tradition, Breyer pointed to three areas where he saw serious reasons for concern. He pointed to a growing body of evidence about wrongful convictions and death-row exonerations, weakening the reliability of the death penalty and increasing the chance of severe miscarriages of justice. Death sentences are handed down in ways that can only be described as arbitrary, with factors like race, wealth, and geography playing a significant role in life-or-death outcomes. Virtually all executions only take place after exceedingly long delays, depriving them of any purported deterrent effect. And compounding those flaws, he noted, was the modern scarcity of the death penalty: A handful of counties in a smattering of states account for most death sentences and nearly all executions, making it even more arbitrary who gets killed by the government.

Ultimately, Breyer reached the same conclusion as some of his predecessors. “In 1976, the Court thought that the constitutional infirmities in the death penalty could be healed; the Court in effect delegated significant responsibility to the States to develop procedures that would protect against those constitutional problems,” he wrote. “Almost 40 years of studies, surveys, and experience strongly indicate, however, that this effort has failed.”

Breyer is known for seeking consensus and collegiality on the court, and he framed his dissent not as a sweeping denunciation of the court and its precedents but as an invitation for his colleagues to reconsider them. Two of his brethren responded with a mixture of indignation and dismissal to that suggestion. Justice Clarence Thomas opined that if the court accepted Breyer’s invitation to rethink its death penalty precedents, it should also revisit its 1976 ban on mandatory death sentences. Antonin Scalia wrote the Constitution placed the decision with the American people and that by “arrogating to himself the power to overturn that decision, Justice Breyer does not just reject the death penalty, he rejects the Enlightenment.”

Some observers, myself included, initially assumed that Breyer was signaling a potential shift on the court itself by inviting such a challenge. But as the justices declined to hear the requisite cases and its approach to capital punishment went unchanged in other ones, it became clear that he was mainly speaking for himself. Breyer did not follow the Brennan-Marshall trend of dissenting from every capital case. Instead he made note of his request and his concerns in those cases that he thought especially warranted it. In a 2018 dissent, he also responded directly to Alito’s declaration that if the death penalty is constitutional, then there “must be” a constitutional way to execute someone.

“These conclusions do not follow,” Breyer explained. “It may be that there is no way to execute a prisoner quickly while affording him the protections that our Constitution guarantees to those who have been singled out for our law’s most severe sanction. And it may be that, as our Nation comes to place ever greater importance upon ensuring that we accurately identify, through procedurally fair methods, those who may lawfully be put to death, there simply is no constitutional way to implement the death penalty.”

Breyer ultimately did not get to see the court reach that conclusion before retiring. Anthony Kennedy’s retirement in 2018 closed the door on hopes for a court-ordered abolition for at least a generation; if anything, the Supreme Court’s six-justice conservative majority is more enthusiastic for executions to be carried out without obstruction than ever before. But dissents are not merely an expression of disapproval or a vain shout into the void. They speak to future generations, and if the Supreme Court ever reaches the same conclusion as Breyer did in 2015, those justices will point to his dissent to get there.