On the evening of February 16, 1961, 19-year-old Wilbert Rideau found himself at a loose end. He’d missed the bus after finishing work in his hometown of Lake Charles, Louisiana, and couldn’t get a ride home with friends until later that night. Dawdling around bus stops alone was dangerous for a Black man. He decided, on a whim, to rob a local bank. “When would an opportunity like this occur again?” he wrote in his 2010 memoir, In the Place of Justice: A Story of Punishment and Deliverance. “The prospect of failure, prison, even death, did not factor into the equation.”

Rideau ended up taking three hostages, killing one, a white woman named Julia Ferguson, in a panic. He was immediately caught, then surrounded by a furious crowd of white men intent on lynching him. “I was living the nightmare that haunted blacks in the Deep South—death by the mob, a dreaded heirloom handed down through the generations,” he wrote. “We had seen the photographs, heard the tales. They would beat me and stomp me … douse my body with gasoline, and set it afire.”

What actually happened was that police dragged him down to the station and allowed his immediate confession to be filmed and then broadcast by a local television station, but without advising him of his right to silence or counsel. With the aid of inept defense lawyers, a Louisiana courtroom gave Rideau a sentence of death. Three times it was voided, due to irregularities in the trial process; and three times a jury resentenced him the same way, each deliberation shorter than the last. It wouldn’t be until 2005, 44 years into a sentence that included over a decade spent in solitary, that Rideau’s crime was downgraded to manslaughter and his imprisonment ended.

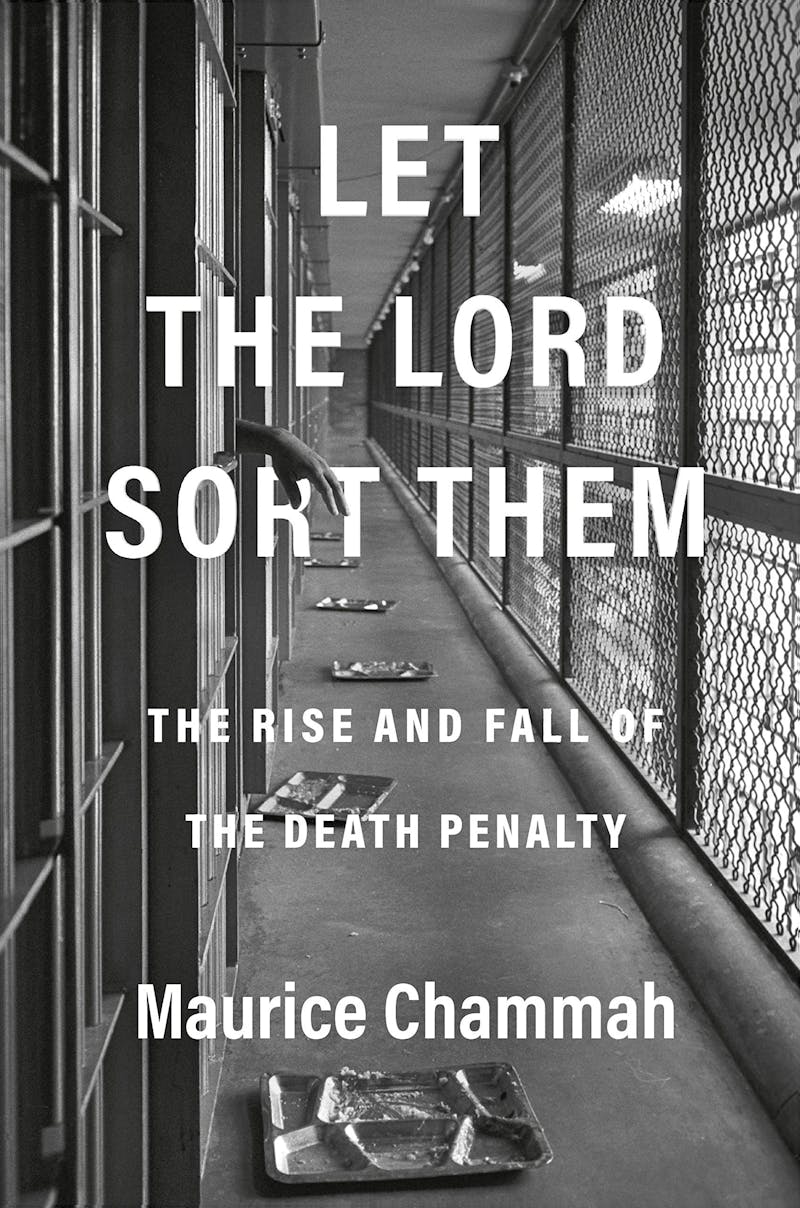

Rideau knew that the fervor buzzing through the crowd on that February night was partly determined by his race, and that the reason they wanted to lynch him was the same reason his trials went the way they did. It’s that place where lynching and capital punishment blur that Maurice Chammah analyzes in his new book, Let the Lord Sort Them: The Rise and Fall of the Death Penalty. Through the perspective of case law, Chammah explains this country’s obdurate commitment to the death penalty, which has found yet another champion, of late, in a president who has raced to execute federal death row inmates in the waning days of his term.

Rideau’s case and others bear out one of Chammah’s key assumptions: Capital punishment is a practice many whites (especially in Texas and the Deep South) have inherited as part of the logic of the Western frontier. In the 1976 Supreme Court case Jurek v. Texas, which reinstated the death penalty, the justices said that the “instinct for retribution is part of the nature of man, and channeling that instinct in the administration of criminal justice serves an important purpose in promoting the stability of a society governed by law.” Only the lawful imposition of the death penalty, they wrote, prevents the flourishing of “self-help, vigilante justice, and lynch law.”

Plenty of jurists and American citizens still hold this as a truism, including former Attorney General William Barr and President Donald Trump. This week, Lisa Montgomery is slated to die at the hands of the U.S. state, bringing the total number of federal executions ordered by Trump to 11—the first of their kind since 2003. In 1992, Barr wrote, just as if it were still 1976, that “the death penalty serves the important societal goal of just retribution.”

The United States is far from the only modern state to use capital punishment, but it is in the minority worldwide and the extreme minority among its own allies in the West. Barr and Trump are long-standing capital punishment advocates, but ProPublica recently reported that their killing spree was planned before the president took office. In a deposition last year, Associate Deputy Attorney General Brad Weinsheimer described how Trump’s first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, got the ball rolling on federal executions shortly after Trump assumed office, with staffers like Matthew Whitaker assigned to put together a drug protocol. That Barr, Sessions, and their underlings got Trump to kill so many people, so fast, and with such opacity around the sourcing of the drugs involved, particularly the controversial phenobarbital, bespeaks a deep, strange problem in America.

In fact, capital punishment is the inheritance of the plantation, Chammah writes, not the frontier—a convincing idea that many of this nation’s judges seem not to share. In 2016, Chammah notes, Judge James Oakley of Burnet County, Texas, responded to the murder of a police officer by a Black San Antonian with a Facebook post reading, “Time for a tree and a rope.” Though a state commission made Oakley undergo “racial sensitivity training,” and he apologized, he couldn’t help but add that “there was never anything racial about my comment.”

“Between 1877 and 1950,” Chammah notes, “more than four thousand African Americans were lynched in the United States.” That the Supreme Court accepted Texas’s argument that execution is a preventative measure against lynching rather than its simple continuation suggests that each fulfills the same desires in the public. Lynching and capital punishment are different cultivars of the same species. “Even in the 1960s,” Chammah writes, “many Texas prisons retained the feel of the slave plantations they had replaced. (In some cases they were actually on the same land.)”

Both sides of the debate around racist bias in capital punishment claim the numbers as evidence for their own case. For example, the percentage of Black murderers sentenced to death has historically been slightly lower than the overall percentage of convicted murderers who are Black. But this “overrepresentation” of whites on death row can be seen another way. As the United States General Accounting Office reported back in 1990, in 82 percent of the 28 death sentence cases it analyzed, the “race of the victim was found to influence the likelihood of being charged with capital murder or receiving the death penalty.” Black people who committed crimes against whites were, in other words, “found more likely to be sentenced to death than those who murdered Blacks.”

The “instinct for retribution” cited by the justices in 1976 seems to be not an absolute truth but a fostered behavior that has its origin in white supremacy.

Chammah’s strength as a writer lies in his synthetic approach, which assesses the law itself and its actors (defendants, defense lawyers) in pretty much equal measure. It’s a book pitched straight into the gulf between universal theory and individual experience. “A murder is physical and intimate,” he writes. A person “pulls a trigger, or thrusts a knife, or wraps a hand around a neck. Police work is physical and intimate, too; detectives take photographs, label pieces of evidence, question suspects and witnesses, and then shackle wrists.” It’s only when the lawyers arrive that “words and ideas take over, as prosecutors and defenders place the evidence in service of a narrative.”

When death is ordered by a court and then subjected to appeal, the crime “returns, for a moment, to the intimacy with which it began. The governor—or, in a federal case, the president—decides whether to grant clemency, holding singular and total power over a person’s life.” If they choose to uphold the sentence, the case flies back to the dingy rooms of some carceral facility, “where a group of men are given a task as intimate as the original killing: another killing.”

In his memoir, Rideau describes the decision to spend his spare time robbing a local bank as a sudden impulse. It was the trial, and the way people discussed and responded to the trial, that made Rideau an exemplar. Let the Lord Sort Them has the icy finality of an autopsy report, and the same intimate particularity.