As I write this in early March, the war in Ukraine is 12 days old and Ukrainian cities, having defied Putin’s expectations of immediate collapse, are beginning to be hit with the massive artillery and rocket fire that is the Russian military’s default position when faced with obdurate, effective resistance from those it is seeking to bring to heel. Ask anyone in Grozny. Or Aleppo.

The shock that the invasion has produced in the United States, in Canada, and in the European Union cannot be overstated. For while in theory any historically literate person knows that until only about three-quarters of a century ago, it was war and not peace that was the constant in human history, the lesson of the post–World War II era has seemed to be one of fewer and fewer wars. And as war declined decade after decade, what might initially have been viewed as historical anomaly would gradually come to be viewed as the norm, a key element of the New Democratic age at which humanity at long last had arrived—the Age of Rights, Louis Henkin dubbed it. (Civil wars, however, are another matter; see Barbara F. Walter’s article on page 17.)

It is important to be measured here. No one—not George Soros, not the human rights movement that pushed us toward what Winston Churchill, speaking of the promise of the new United Nations system, called “the sunny uplands”—thought this was going to be easy. To the contrary, groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, which have been among the avant-garde and emblems of the effort to bring that better world into being, were careful to warn that there would be setbacks. And yet over the past half-century at least, Martin Luther King Jr.’s insistence that, as he put it in his celebrated phrase, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” increasingly became the overwhelming consensus not only in the global north, but even in the global south, in which, though for obvious reasons democratic triumphalists like Steven Pinker are thin on the ground, a somewhat grimmer and more cautious version of the same progress narrative nonetheless also prevails.

Francis Fukuyama’s argument about the end of history by now has come to serve as a piñata for cheap point-scoring in which terrible events are taken as proof that his argument was wrong. Even in some of the coverage of the war in Ukraine, where commentators speak of the “return” of history, Fukuyama is the straw man against whom, consciously or unconsciously, they are arguing. In reality, Fukuyama’s argument was that humanity had arrived at the end of history in the social and political sense. He never claimed that horrible things would not occur in the world, but rather that the human race had reached the point where the age-old debate about what a decent, successful society should look like had finally been resolved. What Fukuyama was arguing, in effect, was that history was long but had bent toward capitalist democracy.

It was in this sense, and this sense only, that history had come to an end. And while some commentators have claimed that the war in Ukraine has changed everything—“WE ARE ALL LIVING IN VLADIMIR PUTIN’S WORLD NOW,” was the way the usually more coolly analytic commentator Ivan Krastev put it—there is actually nothing incompatible between the terrible war Putin has unleashed and the End of History, not least because neither as an economic system nor as a polity is Russia considered a model by anyone, including the many in the global south who increasingly view the Chinese model as one that might end up preferable to the liberal capitalist system that has dominated the world since 1945.

Being horrified by what Putin is doing is not, or at least should not be, the basis for believing the democratic progress narrative has been dealt a fatal blow. This does not mean that the panic in Europe is misplaced. The assumption that there would be no further interstate wars on the European continent proved to be mistaken. but even with hindsight it was not an unreasonable assumption, which is what makes the shock even greater. It also helps account for the EU and, above all, its dominant power Germany having again come around to the view that soft power can never substitute for credible hard power, a view that, though it never stopped being the consensus position in Washington, Beijing, Delhi, and of course Moscow, within the EU was seriously championed only by France. But this is a realization—and a perfectly realistic one, alas—that Putin’s territorial ambitions may not end with having subjugated Ukraine. Putin is seen, rightly in my view, as posing such an existential threat that Germany, by committing to the massive modernization of its military and to France’s cherished project of l’Europe de la défense, has in effect declared that in the future it will no longer be the Germany that still considered itself on some sort of moral probation for Hitlerism. As Emily Haber, Germany’s ambassador to Washington, told TNR’s editor, Michael Tomasky, in March, Germany must “jump over its shadow.”

If anything, the war in Ukraine and the sincere fear in many European countries that if Putin can do this, he can do anything (which means that, however improbable, they may be next), have produced an outpouring of arguments by political figures and commentators that what Putin has really accomplished was not crushing democracy but rather reviving it both from its long slumber and from its crisis of confidence, thus allowing it once more to become a “fighting faith,” literally and figuratively, standing tall for the moral depth of its own tradition. As Fukuyama himself put it in a long Financial Times essay on Ukraine and the crisis of liberal democracy, “Liberalism is valued the most when people experience life in an illiberal world.” This is almost certainly the case. More debatable, however, is Fukuyama’s exhortation that, after Ukraine, “The world will have learnt what the value of a liberal world order is, and that it will not survive unless people struggle for it and show each other mutual support.” Fukuyama carefully conceded that the global democratic consensus of the post-1945 world was badly eroded, and rallying round Ukraine would not alter the deep economic, social, and moral reasons for this. Where politicians like Canada’s deputy prime minister, Chrystia Freeland, have ringingly insisted that democracy is back, Fukuyama sensibly has kept his cool, writing, “The travails of liberalism will not end even if Putin loses. China will be waiting in the wings, as well as Iran, Venezuela, Cuba and the populists in Western countries.” In contrast, Freeland quoting Martin Luther King Jr. on the arc of universe bending toward justice, and her assertion that “Ukraine has shaken the world’s older democracies out of our malaise,” seem less like a considered judgment and more like exhortation tinged by wishful thinking, even if not so categorically as David Brooks writing that Ukraine’s heroic resistance has produced a “restored faith in the West, in liberalism, in our community of nations.”

The problem with this kind of cheerleading, even for Team Democracy, is not so much that it posits that Ukraine’s sacrifice presages democracy’s rebirth, but rather that it revives the complacency not just about democracy’s self-evident superiority but about the fate of democracy being in the hands of democratic countries. This is dangerous ground, and it is all too reminiscent of the kind of rhetoric one heard from American neoconservatives in the 1980s and 1990s about how if the United States was less able to direct the course of world events, this was not the result of new global geostrategic and geoeconomics realities but rather of a failure of American will. On the account of people like Freeland and Brooks, if democracy seems to have seized up over the course of the past decade, it is because it has been unable to blunt pressures from the populist right (as exemplified by Donald Trump’s presidency in the United States, Viktor Orbán’s rise to power in Hungary, etc.) and from the cultural left, for which democracy as understood and practiced by Western democracies is actually bogus—“white freedom,” as the late Tyler Stovall characterized it in his last book. And there is no doubt that this is part of the story. The influence of initiatives like the 1619 Project in the United States challenges America’s most basic democratic bona fides. And the panic in Europe over mass migration from what had been its colonial world has shaken politics and society in Europe to its core and has pushed many Western societies, but most markedly those of the so-called Anglosphere—the United States, the U.K., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand—into a period of intense introspection, above all about colonialism and the persistence of racism in their societies. As Arthur Miller once wrote, “An era can be said to end when its basic illusions are exhausted,” and something of that sort does indeed seem to be happening in the West at the present moment.

And yet, while there is certainly some truth in these explanations, they are, to use the old Marxist distinction, all superstructure and no base. Above all, they do not explain just how much ground democracy has ceded to authoritarianism in recent years. To be sure, statistics can no more tell the whole story of the decline of the global democratic order than can appeals to failures of will. But these statistics are very much worth bearing in mind. One very useful source here is V-Dem, a Swedish think tank based in the political science department of the University of Gothenburg. Founded in 2014, it has for the past six years issued what it calls its annual Democracy Report. In some ways these reports resemble those issued by Freedom House, but the differences in how the two institutions describe and situate their findings are considerable. Freedom House is straightforwardly a policy shop, principally seeking to influence the U.S. government. As the institution’s website puts it, “Freedom House advocates for U.S. leadership and collaboration with like-minded governments to vigorously oppose dictators and oppression, and strengthen democracy around the world.” In other words, it espouses the views of the liberal policy establishment in Washington, which can be summarized as believing that, for all its faults, a U.S.-led international order is preferable to all other alternatives on offer and must be maintained, starting with undoing the damage Donald Trump is assumed to have done to it.

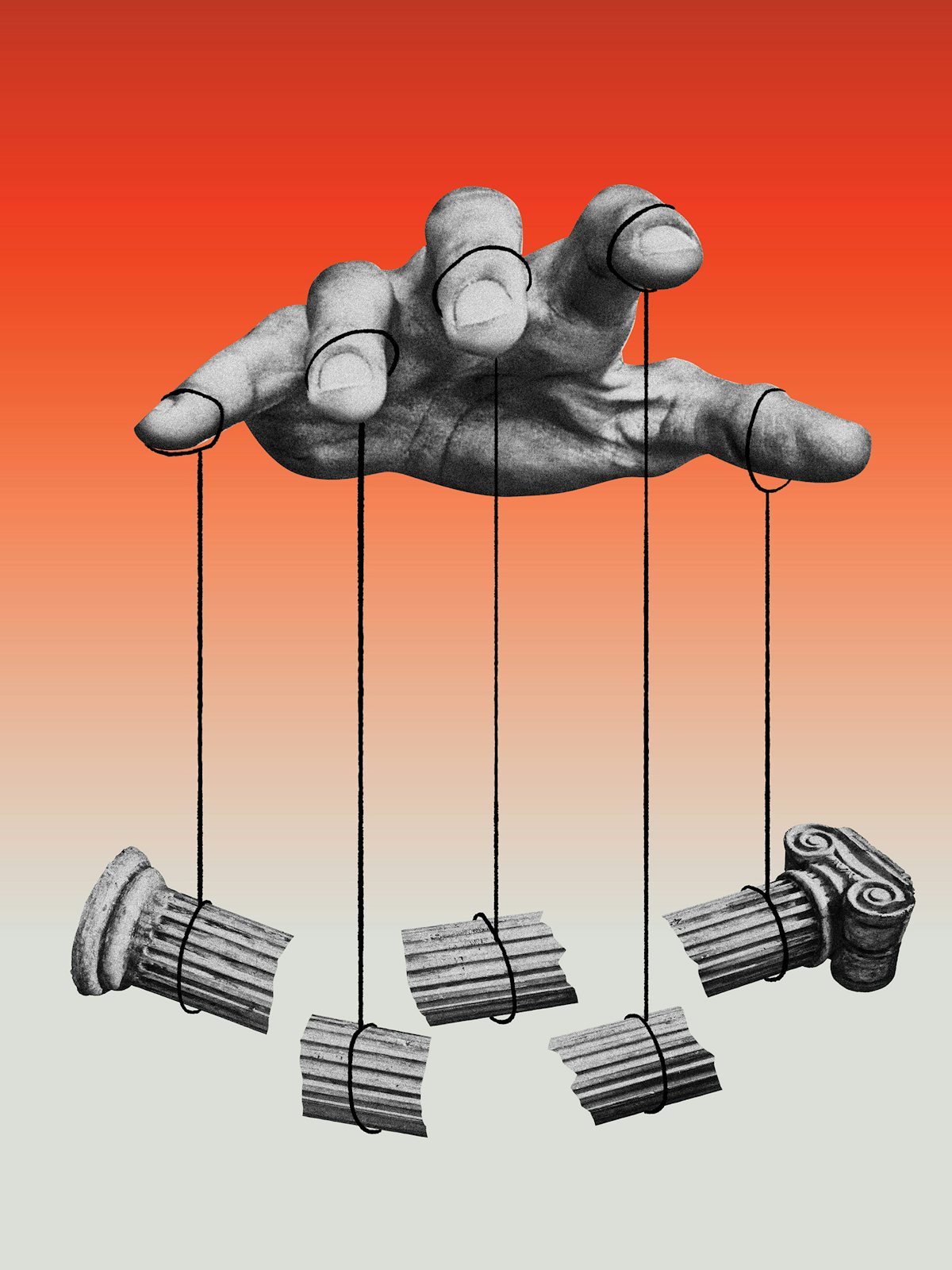

In contrast, V-Dem’s house style is coolly analytic. On its website, it portrays itself as “one of the world’s largest social science data collection projects on democracy.” But it is also frank about its own ideological bent, pointing in particular to its Case for Democracy initiative, which was started with a grant from the European Union, as “[collating] state-of-the-art research on the dividends of democracy for economic and human development, health and socio-economic protections, environmental protection and climate change mitigation, as well as for international and domestic security.” I should say here that I am skeptical of institutions that seek to foster and proselytize for an ideology, and the fact that liberalism in the U.S. sense of the word is, I think, the first secular ideology in the history of the world not to fully acknowledge that it is an ideology (the human rightist subset of this is particularly florid) makes me even more skeptical of them. Nonetheless, strip the polemical character out of what both V-Dem and Freedom House are reporting, and it seems clear that, for the past few years, there are more and more regimes across the world that one hardly needs sophisticated measuring tools to call autocratic rather than democratic. Both Freedom House and V-Dem emphasize how much global resistance there is to the autocratic tsunami sweeping the world, and they are certainly empirically justified in doing so: Think Tunisia, and of course the incredibly courageous young people of Myanmar. Alas, the data they adduce do not offer much reason for optimism. In global terms, it is autocracy, not democracy, that is becoming the rising norm rather than the fated-to-be-eclipsed exception.

According to the 2021 V-Dem report, “Electoral autocracies continue to be the most common regime type.” It says that India, under the Modi government, has been transformed from the world’s largest democracy into an electoral autocracy. These electoral autocracies join the long list of what the report calls closed autocracies. Taken together, these two versions of autocracy are home to 68 percent of the world’s population, while full liberal democracies diminished from 41 countries in 2010 to 32 in 2020, with a population share of only 14 percent. Electoral but not fully liberal democracies account for 60 nations and the remaining 19 percent of the population.

Obviously, the pattern of the previous decade could be reversed in this one. And since hope is a (non-falsifiable) metaphysical category, one can do just that: hope, if one is inclined, that things begin again to start going liberal democracy’s way. But optimism is an empirical category, and there is no particular empirical basis for thinking this. The vastly increased power for the state acquired during the pandemic is not likely to be discarded afterward—at least in most countries, though doubtless there will be exceptions. Meanwhile, the process of the continued relative decline of the Euro-American world compared with Northeast Asia—economic for now, but perhaps soon to be cultural and intellectual relative decline as well—is likely to continue and perhaps (though this is far less sure) accelerate.

Of course, these trends would be far less confounding from a liberal democratic perspective were it not for the fact that in the world’s principal authoritarian state, China, people are not just perceived as living better than they ever have in all of history but are living better, as programs that literally raised hundreds of millions out of poverty have been successful to a degree that is completely unprecedented. If one looks at global development as a whole, one might get the impression that, for all its challenges, global poverty reduction has been going well. But if you strip China out of the equation, the picture looks a good deal bleaker. Add the anticipated effects of climate change into the mix, and it is easy to understand why so many countries in the global south are looking to Beijing rather than to Washington or Brussels for inspiration (whether this will prove to be wise or unwise over the longer term is a separate question).

“First grub, then ethics,” Brecht famously wrote. The promise of Fukuyama’s end of history was that democracy and capitalism came as a package, one never able to reach its full potential without the other. But it is this that the economic successes of authoritarian countries like China and Vietnam call into question. And for many of the nations of the global south, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine simply does not have the same existential urgency it does for people in Europe, North America, and Turkey, and understandably so. It is not that many of these countries support Russia, but rather that the war is simply of little immediate concern. How this will affect democracy’s prospects, though, is not something anyone knows at this point. It is quite possible that in the future the term democracy itself will become unstable. After all, the Hindu nationalist government of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India considers itself to be democratic because it is, or least takes itself to be, majoritarian. And the People’s Republic of China does not concede that it is undemocratic. And now, the Chinese state uses the language of anti-imperialism to deny its own autocratic character. For example, Wang Yi, the Chinese foreign minister, recently said tartly, “Democracy is not Coca-Cola, which, with the syrup produced in the United States, tastes the same across the world.” He might as well have been channeling his inner Ariel Dorfman or Eduardo Galeano! And it was wrong to describe China as “authoritarian,” he said. China was a democracy, he insisted, it was just that China’s democracy takes a different form from that of the United States.

This is a line that is hardly exclusive to Chinese officialdom. In an online zine called Rest of the World that bills itself as “reporting global tech stories,” a recent piece profiles Andy Tian, who is a veteran of both the American and Chinese tech world. He worked for Google and then struck out on his own in a series of ventures, culminating in his current one, a Beijing-based company called Asia Innovations Group (AIG). The company is mainly an app developer focused on its livestreaming platform called Uplive. The app makes money not from its broadcasters—that is, those who livestream on it—but rather from their fans and followers, who are encouraged to give them virtual gifts. A percent of the cost of each one of them is taken by Uplive. In a recent interview, Tian offered his own version of Wang Yi’s argument about democracy taking a different form in China than it had in the United States. The first stage of tech innovation had been in the United States, Tian insisted. But Chinese entrepreneurs such as himself were going to change all that. “What’s the next stage of [tech] evolution?” he asked rhetorically. And answered his own question. “[Those of us] based in emerging markets,” Tian boasted. “We are taking over.” And then he concluded with a flourish. “We’re decolonizing,” he said. That may seem like nonsense to most people in the global north. But Tian isn’t speaking to them. And the fate of democracy is much more likely to be decided by those people in the global south to which his words are addressed than by what happens in Ukraine.