Last December, The Washington Post’s Dana Milbank wrote a chilling column. He asked a data analytics firm to do a “sentiment analysis” of the press coverage received by President Joe Biden in the first 11 months of 2021 as compared to that received by President Donald Trump in the previous year. The firm looked through some 200,000 articles across 65 media outlets. Its algorithm weighted certain adjectives based on where they were placed in a news story.

Result? After an initial honeymoon, Biden received coverage about equal to—and sometimes worse than—that accorded Trump. “Think about that,” Milbank wrote. In 2020, Trump was presiding over a historic pandemic; the economy was crashing; tens of thousands were dying; and he was telling people to inject bleach. On the campaign trail, he attacked voting rights and democracy, endorsed conspiracy theories, and said he wouldn’t accept the election’s results if he lost. In 2021, starting in the summer, Biden definitely ran into political problems: inflation, the delta and omicron variants, his own Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Joe Manchin. But he did not serially lie about a nonexistent “deep state” conspiracy against him or levy regular attacks on the institutions of our democracy.

And yet, Trump got coverage as good as or better than Biden got once his approval numbers started to fall.

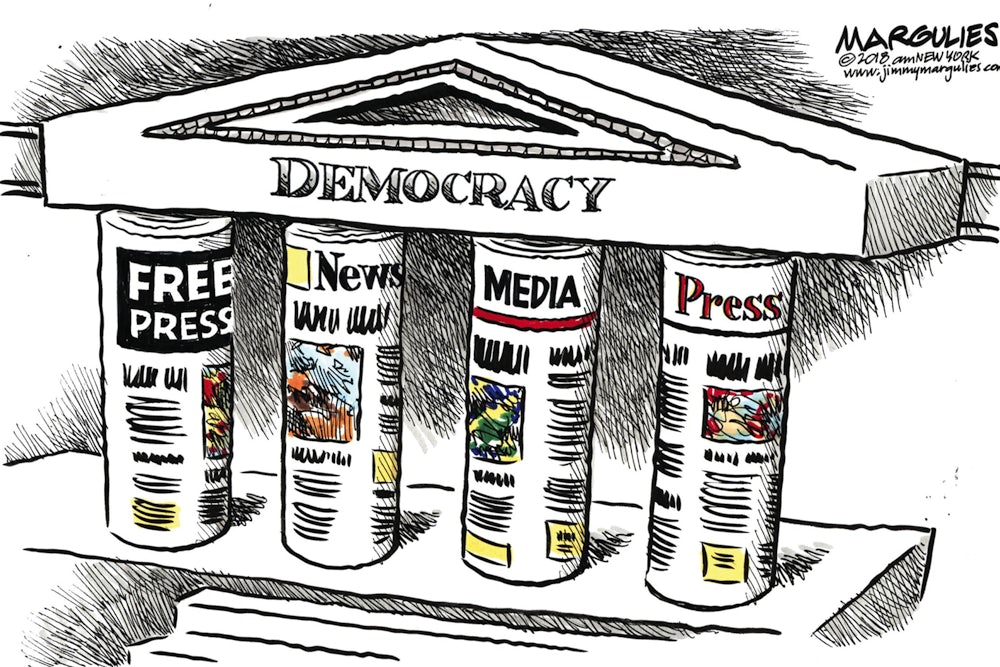

When we think about our democracy, we have to think about the press. The First Amendment comes first for a reason. James Madison’s original proposed wording went: “The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.” In his mind and the Founders’ generally, the role of a free press as a guarantor of liberty and democracy was clear.

So the press must have the right of the freedom to publish material that discomfits those in power. But it also has a responsibility: to uphold the best values upon which this country purports to rest. When it gives Trump an easier time than it does Biden, is it doing that?

This question is not about liberal versus conservative, or Democratic versus Republican. It’s about democracy versus anti-democracy. The press, Milbank wrote, must be partisans—not for a politician or party, but for an idea—“partisans for democracy.” He continued: “The country is in an existential struggle between self-governance and an authoritarian alternative. And we in the news media, collectively, have given equal, if not slightly more favorable, treatment to the authoritarians.”

We in the political media now—that is, the honest political media; the right-authoritarian media is another problem—must ask whether we can be partisans for democracy. Doing so will require shedding some long-held assumptions about objective journalism. But if we’re going to play a part in saving democracy, we have no choice.

I remember that in the 1990s, when polarization was first strangling our political culture, the standard reflex was to blame both sides. Indeed, “both-sidesism” became a term of scorn among some liberal commentators, as we watched Newt Gingrich toss grenade after grenade into the civic bloodstream and a few Democrats try to respond wanly in kind, and then had to endure reading the media panjandrums of the day, like David S. Broder, sniffing that both sides were equally guilty.

The key word there, of course, is equally. Obviously, Democrats and liberals helped contribute to polarization. They’re politicians, not saints. But anyone who couldn’t concede that Gingrich, Tom DeLay, and Karl Rove were driving that bus, or that the Republican Party was moving far more aggressively to the right than the Democrats were to the left, was in denial—committed to an ideology of avowed centrism that is every bit as ideological as anything you’ll find on the “extremes.”

Reality eventually discredited this posture. Not that a whole lot of people still don’t hold this view. They do. And straight news organizations like, say, the Associated Press have struggled with how to report on a Washington in which one side repeatedly says that tax cuts pay for themselves or that Saddam Hussein was behind 9/11 and was a threat to attack the United States. But as the years passed—the Bush years, the Obama years—more and more people started to acknowledge the truth of the situation: One side was hewing roughly to the facts, allowing for the standard politician’s penchant for presenting truth in the most self-serving light possible, while the other side was mocking what it derisively called the “reality-based community” and “just asking questions” about whether Barack Obama was an American citizen.

That was the situation through 2015. Then came Trump. Now the right wasn’t merely operating from its own set of “facts.” Now, under Trump’s direction, given his habit of telling whatever lie was necessary in the moment and his psychological need to crush people, those facts were handed a new context, placed in service of a new goal—not just to defeat liberalism within the existing democratic rules, but to obliterate it. And to obliterate it, the breaking of the existing democratic rules would have to be tolerated. Not just tolerated, but embraced. Trump unleashed that part of the right-wing id that never had much use for democracy anyway—that saw American democracy as having abandoned its economic interests and, far less defensibly, felt (and feels) deeply threatened by the idea of a multiracial democracy in particular.

This is what so many media organizations failed to see clearly, right up until January 6, 2021. Well, what’s past is past. The question is, now that January 6 has happened—now that we have seen a sitting president try to orchestrate a coup d’état on his own behalf—what is the press prepared to do about it?

There is some good news emanating from Milbank’s own Washington Post, which announced in February that it was creating a team to cover, thoroughly and systematically, the democracy beat. Matea Gold, the paper’s national editor and before that an aggressive reporter on money in politics, will oversee the team. In an interview, she explained how the beat will be set up, and it sounds promising. There will be two editors and six reporters initially—at least three based in Washington, and the rest spread out around the country, in Georgia, Arizona, and the Upper Midwest. She said they’ll be reporting on the “actual mechanics” of the vote in those places, election administration, and voters’ eroding trust in the system.

That sounds good. But if all this reporting and editing just ends up pulling its punches in the name of “objectivity,” the Post won’t be acting as a partisan for democracy. Gold vows: “We go where the facts take us. We do not shy away from where the story goes.” She points to the fact that the paper “was very direct in saying, for example, that the former president was lying about election fraud.”

That’s true, it was. One shouldn’t doubt the paper’s admirable intentions here—a dedicated head count of eight people is a major commitment and expense, even for a large newspaper. The New York Times, in contrast, has not announced any specific commitments to a democracy beat. (Executive editor Dean Baquet declined to be interviewed for this article.) But the question still looms as to whether the mainstream American media can not only call a lie a lie, but whether it will be willing to do so day after relentless day, as the attacks on democracy mount and multiply, or whether it will feel compelled, in the name of “fairness,” to back off, balance things out, present the “other side” in a debate (democracy versus anti-democracy) in which there is no legitimate other side.

Margaret Sullivan, the Post’s media columnist, argued to me that this is the real challenge, not just for her paper’s team, which she applauds, but for the mainstream press generally. “The topic hasn’t been given the centrality it deserves,” Sullivan told me. “So that is what I would like to see … to center it and to try to get across to people that this is not just like some other random story that we cover, but it is an existential threat.”

One of the ways to do that, she suggested, is to find a way to label the coverage—package it in a way that shows plainly to readers that this is different from the usual news diet, more important. She pointed to the example of The Boston Globe putting its coverage of child abuse in the Roman Catholic Church under the “Spotlight” rubric. “I think that can help focus things,” she said. “And I think it can also kind of give a reason to do stories that don’t have an immediate, intense breaking news aspect.”

That last point is vital. Some assaults on democracy are “news” in the traditional sense—January 6, obviously, or the passage of a voter-suppression law in a state. But others aren’t big news. A random remark by Trump or Kevin McCarthy may be on its face a small thing. But its implications might be enormous. Reporters and especially editors will have to recalibrate their ideas of what counts as news.

When we give and get awards, the political press likes to congratulate itself on being the guardian of democracy. For decades, those were mostly feel-good words that weren’t really being put to the test. In these next two years, they will be. There were times in our country’s history when it could be argued that balance was more important than truth, which after all was open to interpretation. This is not one of those times.