Like

any good economic euphemism, “quantitative easing” evokes the soothing prospect

of crisis averted and equilibrium restored. The term—coined by former Federal

Reserve Chairman Benjamin Bernanke to keep interest rates at (and later below)

zero for the high-powered banks obtaining cash at the Fed’s discount

window—neatly conveys a sense of close forensic care paired with the aura of a

safe landing in progress: It says, in essence, “Everyone’s in good hands now.”

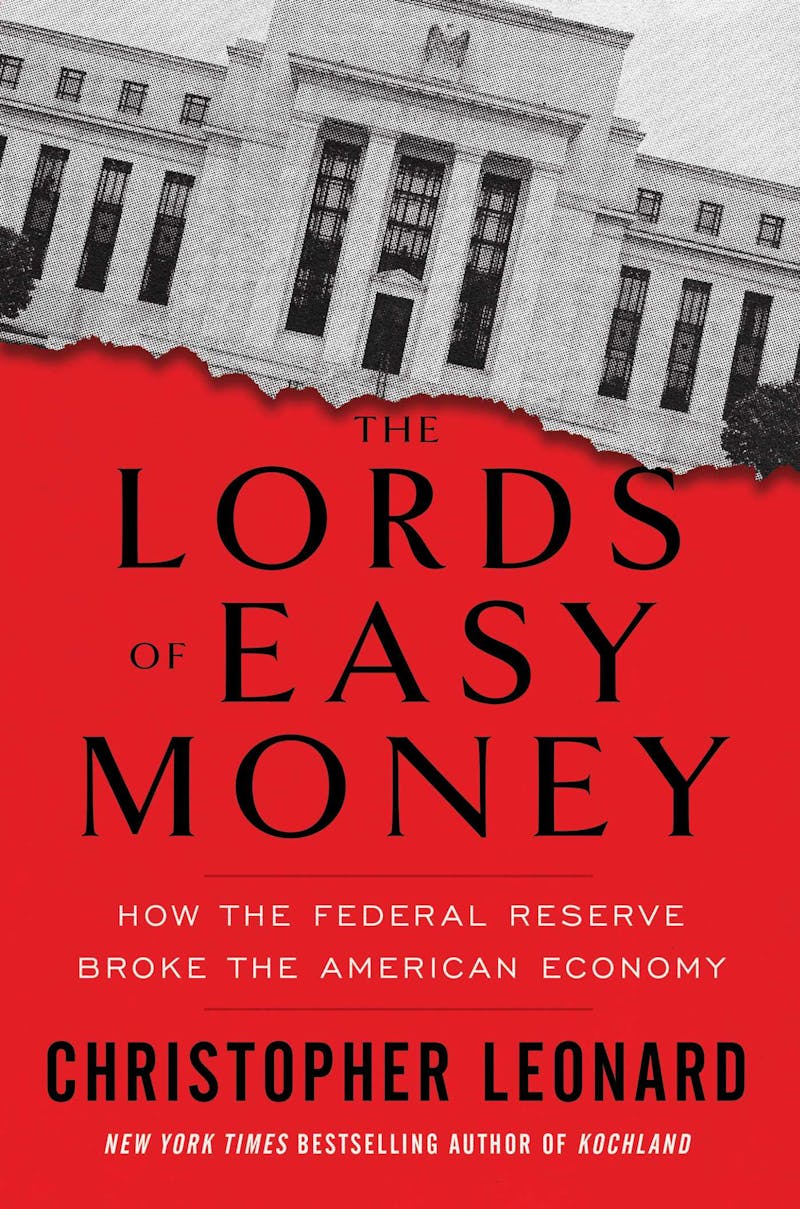

Only, as business journalist Christopher Leonard makes clear in The Lords of Easy Money, his bracing and closely reported chronicle of the Q.E. era and its legacy, the real meaning of the term is much closer to: “We’re going to create asset bubbles like you would not believe.” Bernanke pioneered the de facto free-money policy in an effort to keep the slow-rolling recovery from the 2008 economic meltdown on track—and particularly to bring down the rate of unemployment, which was still, some two years later, hovering close to double digits. The Fed first experimented with the policy in the depths of the Great Recession, taking the unprecedented step of directly purchasing a chunk of the country’s flailing mortgage debt to stabilize the mortgage market. But in 2010, Bernanke proposed something much more far-reaching: an initiative to disburse interest-free loans to major banks to unloose new tranches of cash throughout the economy. Bernanke’s Fed pledged to inject $600 billion of quick-turnaround Q.E. money into the economy in a matter of months—a quantum shift in the Fed’s monetary policy, since as Leonard writes, “before the crisis, it would have taken about sixty years to add that many dollars to the monetary base.”

At the same time, Bernanke acted to foreclose on safe-money harbors for investors in order to get them spending at higher frequencies and greater volumes: By retiring long-term government debt in 10-year Treasury bills, the Fed was pushing all this new free investment capital directly into downstream outlets sure to outperform the now-lowered return on Treasury bills. “The theory was that banks would now be forced to lend money, whether they wanted to or not,” Leonard writes:

Quantitative easing would flood the system with money at the very same moment that it limited the refuge where that money might be safely stored. If economic growth was weak and fragile during 2010, then quantitative easing would shower the landscape with more money and cheaper loans and easy credit, enticing banks to fund new businesses they might not have funded before.

However, as Q.E. became the country’s baseline monetary policy over the next decade, a very different dynamic kicked in. As markets became awash in untrammeled tidal waves of cash, the investment economy came more and more to resemble a desperate money laundering operation, frantically seeking to jury rig anything that might plausibly be presented on paper to investors and regulators as a productive enterprise, regardless of actual economic performance on the ground. The long-venerated formulas of profitable investment were thus functionally reversed, with footloose capital spinning off into ever more baroque and dodgy instruments of its own devising, and the underlying assets of the real economy left to stagnate in a state of malign neglect.

The results of the first round of Q.E. were decidedly equivocal and uninspiring: Job growth remained anemic, while much of the mainstream business press fretted over a paper-fueled bout of inflation that never materialized. So Bernanke began pressing for a newer, bigger round of quantitative easing in the summer of 2012. He signaled to investors, in speeches and press interviews, that more free money would be in the pipeline. Meanwhile he was quietly lobbying the 12 regional members of the Fed’s Open Market Committee, or FOMC—the body that approves policy recommendations by the Fed chair—to present a united front behind the new Q.E. push, which would start with a $500 billion outlay but would proceed on an open-ended basis following that, based on economic conditions.

Before their vote, Bernanke had some Fed economists prepare a presentation on the benefits of extending still more free money to Wall Street in even greater volume, to make the case that this new infusion would be an emergency measure, easily walked back, and containable within the familiar channels of monetary policy that the Fed had managed throughout the crisis. The copiously documented forecast turned out to be “catastrophically wrong in virtually every important prediction that it made,” Leonard writes. The report claimed that after rates remained at zero through 2013 and 2014, things would gradually return to a still growth-friendly but less overheated status quo, with short-term interest rates around “4.5 percent or more.” In reality, the rates remained at a minuscule 0.4 percent at the end of 2016 and were at less than 2 percent by mid-2018—less than half of the rate targeted under the new Q.E. initiative.

What happened in reality was that Wall Street, already primed for free money on virtual demand, displayed an insatiable appetite for more. The Fed’s limited $500 billion spree rapidly ballooned into more than $1 trillion by the end of 2013; the assets on the Fed’s balance sheet also skyrocketed, to $4.2 trillion by 2016, where the number stuck through the next two years. The sober FOMC report, by contrast, predicted a peak of $3.5 trillion over the first stretch of the new Q.E. effort, off-ramping to a modest $1.9 trillion by 2019.

And macroeconomic forecasting aside, the other big problem with Bernanke’s plan was where all this cash was accumulating. Bernanke, recall, was trying to goose up the lagging labor economy—but his zero-interest-rate policy (or ZIRP, as investors dubbed it) chiefly lubricated the highest reaches of the investment world. The reason was again embedded in the logic of the whole thing, as Leonard explains:

The asset price inflation was not an unintended consequence of qualitative easing. It was the goal. The hope was that higher asset prices would create a “wealth effect” that bled out into the broader economy and created new jobs. It was entirely clear to senior leaders at the Fed that to achieve the wealth effect, ZIRP must first and foremost benefit the very richest people in the country. That’s because assets are not broadly owned in America, according to the Fed’s own analysis. In early 2012, the richest 1 percent of Americans owned 25 percent of all assets. The bottom half of all Americans owned only 6.5 percent of all assets. When the Fed stoked asset prices, it was helping a vanishingly small group of people at the top.

Small

wonder, then, that when Bernanke gingerly announced plans to start unwinding

the Q.E. giveaway plan in 2013, as overall growth waxed and some parts of the

labor economy seemed poised to recover, Wall Street went into panic mode, with

a market downturn that business observers soon labeled “the Taper Tantrum,” in

homage to Bernanke’s mild pivot away from the Fed-backed asset bubble.

Investors started to flee from the higher-risk outlets the Fed had been coaxing

them into all this time, and Treasury rates spiked sharply. Betsy Duke, one of

the FOMC skeptics of redoubled quantitative easing, who had only gone along with

it after Bernanke’s charm offensive reassured her that it could be smoothly

walked back, now saw the writing on the wall: The Taper Tantrum “forced the Fed

to be even more committed to continuing on. The continuing of the

purchases—there just kind of wasn’t any choice at that point. They had to

continue, and had to bring reassurance to the market that they were going to

continue.”

And

so they did. As cash continued to roar through the banking system, nimble

brokers and fund managers flocked to a formerly obscure financial instrument to

swoop up the metastasizing debt: the collateralized loan obligation, or CLO. Like

the collateralized debt obligation—its infamous cousin that helped nearly to

topple the global economy in 2008—the CLO repackaged risky, dubiously leveraged

debt into tranches that big funds continued to flip into bigger returns and

banking fees. The problem, of course, is that the booming CLO market, like its

CDO predecessor, spun out into a speculative frenzy and became divorced from

actual underlying economic conditions.

Vicki Bryan, an analyst of junk bonds devoted to uncovering fraud and incompetence in the offerings so that investors could either dump them or price up the interest financing them, noticed at the height of the speculative binge over 2014 and 2015 that her findings had no impact. “It’s been a result of what the Fed started to do in 2010, and continued to do later,” she told Leonard. “You’ve got an artificial bottom, and the higher part of that bottom is set by the Fed. So you can’t lose in this market. And if you can’t lose, it’s not really a market.” Over the Q.E. era, the CLO market more than doubled, from shy of $300 billion in 2010 to $617 billion in 2018.

The other major bubble indicator that stormed through the markets was the stock buyback—another comparatively rare instrument in the pre-Q.E. age because of the enormous debt risk attached to it. But in the false-bottomed market of the 2010s, buybacks abounded; in just one high-profile case, Forbes found that McDonald’s borrowed $21 billion in bonds and notes between 2014 and 2019 and then proffered more than $50 billion in buybacks to investors, all while only realizing $31 billion in profit. For far less robust businesses in the market, this new upside-down logic of debt financing ate directly into their equity, rendering them still more vulnerable to downturns and takeover bids. Leonard chronicles the fortunes of a Milwaukee-based manufacturer of industrial parts called Rexnord (like much its bubble-driven financing, the company name had no underlying referent or meaning). After the massive private equity fund Carlyle Group acquired the company—under the watch of future Fed Chair Jerome Powell—back in 2006, Rexnord was whipsawed by successive debt-driven takeover bids. Carlyle spun it off to another large equity firm, the Apollo Group, which in turn launched a raft of CLO offerings around the company—and so on, down the Wall Street assembly line of debt that Leonard dubs “the risk machine.” The upshot was that Rexnord acquired an entirely new economic reason for being; as Leonard observes, the company “had become … emblematic of the private equity world. It was no longer a company that used debt to pursue its goals. It now was a company whose goal was to service its debt.”

And how. In 2014—a year in which Rexnord clocked a cool $2 billion in corporate debt—the company paid $109 million in interest while realizing just $30 million in profit. Defying all traditional market logic, the company’s board authorized a $200 million stock buyback in 2015 and another $121 million in buybacks over the next two years. In order to keep the company attractive to the debt barons on Wall Street, Rexnord shuttered a major ball-bearings factory in Indianapolis, moving the plant and its 300 jobs to Monterrey, Mexico.

Leonard recounts this saga via the powerful and enraging story of a machine operator named John Feltner, who had been hired there after driving 15 hours from his home in Dallas for his job interview. He and his wife settled into a suburb outside Indianapolis and started saving to buy a home. Feltner was a union representative at Rexnord, and during the 2016 campaign, when Donald Trump made a big, and mostly empty, show of fighting to keep another big Indiana manufacturer, the Carrier air-conditioning company, from shipping another 700 jobs to cheaper global labor markets, Feltner declared his allegiance to the GOP nominee. But when Feltner and his fellow workers took to the media to try to win Trump’s attention to their plight, the campaign fizzled; when Trump won the presidency, his interest in touting the cause of displaced workers predictably atrophied, and Trump gravitated back to his own and the GOP’s natural constituency: the same investment houses consigning the operations of industrial America to their debt ledgers.

Trump did surprise some market watchers, however, by appointing Jerome Powell as the Fed chair; Powell, thanks in part to his close ties to Wall Street, was an early Q.E. skeptic when he came on board the Fed Open Markets Committee. However, in the wake of the Taper Tantrum, Powell came to embrace Bernanke’s program as a virtual inevitability—and that conviction was sealed when Powell confronted a crisis in the Fed’s “repo market”—the intrabank short-term loan program that financed many debt-driven acquisitions. In repo transactions, Treasury bills—always the safe harbor for risk-averse investors—were put up as collateral for these loans. But in September 2019, the rates for these transactions started to rise at alarming rates: They reflected the growing worry among lenders that banks now lacked the cash reserves to cover the loans. Normally, a 0.3 percent hike in repo rates was a warning sign; now they were going up by as much as 2.5 to 3 percent—and would eventually go up over 9 percent.

It turned out that hedge funds—major players in the whole Q.E. transformation of the investment economy—were tapping out repo funds. And to make matters more maddeningly opaque, the Fed couldn’t fully measure the scale of the hemorrhaging, since hedge funds, as lead institutions in the so-called shadow banking system, weren’t required to divulge the content of their books to the Fed. It was only clear that, like the rest of the paper economy, hedge fund transactions in the repo market scaled up dramatically under Q.E.—from roughly $1 trillion in 2008 to roughly $2 trillion in 2019. With the specter of another secular market meltdown taking shape, Powell’s Fed orchestrated still another massive bailout—but one so cloaked in the dreary bureaucratic argot of Fed policy that Leonard calls it “the invisible bailout.”

The worry, as Leonard summarizes one forensic report on the crisis, was that “if the repo market were closed off to hedge funds, they’d be forced to liquidate Treasury bills and mortgage securities at a level that was twice as large as the amount liquidated in 2008.” In other words, after years of quantitative easing, the Fed had narrowly skirted a “forced liquidation event that could be twice as large as that in the horrific crash of 2008.” What’s more, Leonard notes, “this was all happening during the apparently sunny weather of a market boom, when markets were not just stable, but rising.” Appropriately panicked, Powell’s Fed moved to shift $75 billion over to the tanking repo market on the first day the meltdown threatened, and a month and a half later, it was boosting the repo market by $10 billion a day.

The following year, of course, saw a genuine crash, with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and urgent public health measures that locked down a good deal of the American economy. The Fed continued seeding new bailouts in response—and when Congress passed the 2020 Cares Act to directly fund income transfers to American businesses and households, Washington oversaw “the largest expenditure of American public resources since World War II.” But true to Fed form, “the economic recovery of 2020 was a gated recovery, with the money flowing to selected, exclusive zipcodes,” Leonard writes. “The middle class had experienced a long and deep slide in its earning power, bargaining power, and wages. Virtually nothing had changed this trajectory during the decade between 2010 and 2020. The economy had grown, but the growth was shared by a smaller and smaller share of the population.”

In some ways, this outcome is completely to be expected: The Federal Reserve is arguably among the first, and certainly the most powerful, captive regulatory agencies—i.e., bodies of federal overseers serving the interests of the entities they allegedly are supposed to curb in the public interest—in the modern era. Progressive reformers cribbed its structure from the Populist Party’s radical subtreasury plan, which sought to weight currency value to labor and crop exchanges. But of course, in the pursuit of finance-sector stability, the architects of the new Federal Reserve System handed total authority to the banking industry—the agent of a vast and growing amount of economic instability in industrial-age America. No representatives of the classes of Americans living at the bleeding edge of such market convulsions were granted seats on the Open Markets Committee; their plight was typically addressed in bloodless Fedspeak that monitors unemployment rates and fluctuations in commodity prices. (Even inflation, the great bugaboo of the Fed policy elite and the financial journalism world alike, typically benefits debtors who are often pressed to obtain loans on terms far less generous than those afforded the hedge funds in the repo market, since depreciated currency represents lower interest payments over the term of a loan—which is why the nineteenth-century Populist movement also agitated against the gold standard.)

Leonard’s book is an indispensable account in many respects—his coverage of the invisible bailout of the repo market alone stands as a bracing case study in how the false pieties of quantitative easing directly stoked ruinous asset bubbles. But Leonard is also that rarest of financial reporters who conscientiously tracks the real-life consequences of the Olympian deliberations undertaken by the paper economy’s gatekeepers. All too many chronicles of monetary policy and market convulsions focus on outsize masters-of-the-universe storylines—be it the policy ruminations of an Alan Greenspan or Paul Volcker, the lurid Treasury-looting deals struck by a Michael Milken or an Elizabeth Holmes, or the in-a-class-by-himself market delusions of Donald Trump.

Leonard archly notes that the full implications of the Q.E. era escaped public notice in real time thanks to an American media ecosystem that “was fractured and degraded in 2010 in ways that both mirrored and accelerated the decay of America’s democratic institutions.” In The Lords of Easy Money we have a richly reported, accessible, biting, and long-overdue remedy to that system failure.