On December 21, 2021, the attorneys general of 16 states, including agricultural powerhouses like Iowa and Minnesota, sent a letter to Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack and his fair-competition czar, senior adviser Andrew Green. In it, they called on the U.S. Department of Agriculture to enforce the Packers and Stockyards Act, initially passed in 1921 to check rampant market manipulation and fraud in the meat industry. The timing of the letter wasn’t accidental. A White House analysis released earlier that month showed that the profits of the country’s biggest meatpackers has soared 300 percent. Attacking Big Meat now slots into the Biden administration’s increasing focus on antitrust in the face of rising inflation: The White House seems to hope that cracking down on corporate concentration can rein in runaway food prices on consumer goods like meat, winning goodwill before November’s midterm elections. Now its plan for that has become clear. On Monday, the White House announced a $1 billion investment aimed at promoting fair competition in the meat industry, with a focus on expanding the processing capacity of smaller and independent slaughterhouses and cracking down on violations of competition laws.

Attacking the meat oligopoly has its economic and political virtues. America’s major meat processors regularly jack up prices, expose workers to heinous working conditions—and, most recently, to Covid-19—and profit from widespread animal cruelty. But $1 billion just to stimulate competition against them from smaller firms is both not enough and far too much.

The White House plan assumes that the main problem with big meat companies is their size; more numerous, smaller processing companies would therefore be better, providing the same quantity of the same products, more reliably, and at lower prices. But, on the one hand, there is no guarantee that even a billion dollars can stimulate that sort of change in the meat market absent much stronger regulatory crackdowns on the multibillion-dollar meat giants. On the other, it is far from clear that what the U.S. needs is more meat companies given its ostensible commitment to meeting climate targets. If anything, the administration should focus on policies that would force the meat industry to pay the full price for the environmental and public health problems it causes. But accounting for these so-called externalities would mean making meat far more, not less, expensive.

The American meat industry is more concentrated today than when the Packers and Stockyards Act was passed 100 years ago. Then, five huge companies controlled upward of 70 percent of the meat market. Today, the top four processors in beef, pork, and chicken control, respectively, 85, 70, and 54 percent of their markets. Processors like Tyson and Cargill are middlemen: They sometimes own their own farms, but more often they buy live animals from farmers, slaughter them, process them into cuts like bacon or burgers, and sell those to restaurants or retailers or export them.

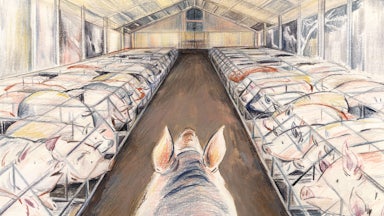

When only four companies play this role in huge industries, this gives them tremendous leverage over both regulators, such as the USDA, which are supposed to keep them in check, and over the entire meat value chain from farm to supermarket. For farmers, this leads to a monopsonistic relationship, where most animals are not sold on the open market but through direct contracts with processors, who can impose low prices and force high debt in relationships that have been compared to sharecropping. For retailers and consumers, this can mean higher prices completely unrelated to higher production costs. Major processors like Smithfield, JBS, and Tyson are regularly sued for alleged price-fixing and even for using complex software to facilitate collusion on prices. They are frequently forced to pay multimillion-dollar settlements. In 2016, one lawsuit alleged that price-fixing by the chicken industry alone costs the average American family over $300 per year. (The industry has disputed that it colludes on prices, attributing recent price spikes to increasing input prices, supply chain bottlenecks, and both labor shortages and higher wages paid to incentivize workers back into abattoirs.) Consolidation also gives processors massive leverage over their poorly paid workers. Giant, centralized slaughterhouses operate at breakneck speeds and are hazardous workplaces, but with minimal government regulation and few unions, processors rarely feel pressure to improve wages or working conditions. Farmers, workers, and consumers looking to do business with kinder, gentler meatpackers have few options to choose from, and they’re all terrible.

All of this makes Big Meat ripe for government intervention. Antitrust action can indeed fight the practices and results that price-fixing lawsuits have complained about in highly consolidated industries like meatpacking. Trustbusters aim for a more crowded and competitive marketplace that drives down processing costs and reaps rewards for both farmers and consumers. Farmers would have more potential buyers, consumers more sellers, and workers more employers. Although the Biden plan has some provisions to crack down on collusion, its main action along these lines is to invest in “independent” processors, in theory bringing new players into the market and giving them the financial backing to go toe-to-toe with the big boys. The plan provides $375 million in grants and $275 million in additional loan support to help build new, independent processing plants, and then rounds out the billion with funds for workforce training, technical assistance, research and development, and inspection-fee waivers. All of this comes out of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act’s $1.9 trillion.

As far as trustbusting goes, however, this is unusually weak sauce. While $1 billion may be large enough to boggle your mind, it’s actually chump change in the titanic meat industry that does hundreds of billions dollars worth of business in a year. It may take years for new plants to be built, pass inspections, and to come on line, meaning little of this $1 billion is likely to help either consumers or farmers today, or even by November.

Then there’s another problem: Introducing more players into a market defined by a high-volume, low-margin production may temporarily increase competition, but it would take sustained government intervention—either through the continued subsidization of independent processors or by actually breaking up large players—to prevent such a market from reconsolidating. Absent active government oversight of the strong sort suggested by the attorneys general back in December, the big processors will simply wait for the right moment to do what they’ve always done and gobble up the independent processors. In the shorter term, major processors may just keep charging high prices because the small players can’t move enough volume to reliably meet the demand of major retailers or restaurants. Since these measures do nothing to alter the fundamental labor dynamics of processing itself, which, even in “independent” plants, will still be done at breakneck speeds by a workforce disproportionately composed of immigrants of color, they offer only the promise of many more, slightly smaller exploiters.

Trustbusting alone is a sisyphean task, with the boulder of reconsolidation rolling back down the hill the moment government scrutiny and political pressure eases. If meat prices—either because of the White House’s actions or other market dynamics—dropped back to 2020 levels, would trustbusters have the political juice needed to keep meat processors small? If not, this $1 billion would be throwing good money after bad. And if competition and collusion are really the problems, why not, as Matt Bruenig suggests, simply nationalize one of the major players? That would end the alleged cooperation practices critics claim are the heart of the problem. There is no political will for such a radical solution, but that’s largely because there’s no political will for any real solution at all.

However we may deal with competition in meat processing, it may be merely menu planning on the Titanic. Biden’s approach is a weak pass at a decent idea: breaking up a few corporations’ stranglehold on consumer goods. But it also takes government policy further down the path of subsidizing the price of meat and away from what science tells us planetary health requires. Government policy already directly subsidizes a steady flow of cheap animal feed that helps keep meat prices artificially low. And thanks to lax regulations, “our government subsidizes the giant meat corporations indirectly by allowing them to push devastating costs onto the public with impunity,” explains Yale Law School’s executive director of the Law Ethics and Animals Program, Viveca Morris. What do those devastating costs look like? A huge contribution to climate change, increased risks of zoonotic illnesses and antibiotic resistant bacteria, brutally exploited workers, polluted landscapes and waterways, deforestation, metabolic illness, heart disease, diabetes, and abused animals.

The unfortunate reality—still considered a political third rail—is that the only policy that would address these costs would be one that reduces the amount of meat produced. Truly sustainable policy would mean ensuring that the price of meat reflects the real cost of meat’s production, no matter how upset that would make consumers. Something like Senator Cory Booker’s Farm System Reform Act would be a start (though we’d also recommend abolishing the USDA). Making sure these kinds of changes don’t simply increase food inequality would take thoughtful planning, as well.

Building back better slaughterhouses and promising lower prices might seem like a good midterm strategy right now, but it’s hardly a fail-safe political plan. In the long run, serious action on climate change and corporate concentration in animal agriculture will require facing the catastrophic price of cheap meat. Telling American consumers they have a government-backed entitlement to cheap meat will make that future, inevitable reckoning all much more painful for Democrats.