For those of us who grew up enjoying (and have grown old romanticizing) the bright, resplendent four-color pleasures of comic books, it may be time to admit we’ve been had. It may once have seemed that comics offered intelligent young men and women an escape from the awfulness of middle-American life. But seeing today how thoroughly those serial fantasies have infiltrated every aspect of modern culture, it’s beginning to look as if comics largely reinforced our worst impulses and instincts.

From their early days, comic books taught kids about a Manichaean universe in which subterranean, irrational, and irredeemably evil forces continually threatened society’s superficial order. The popular, early detective strip Dick Tracy envisions criminals as creatures from the “lower orders,” such as a “tramp” who flagrantly steals rides on trains (and murders the hard-working guard who tries to stop him). Later they develop into genetically twisted, born-bad mutant-freaks such as Mumbles, Pruneface, Flattop, and the Mole—a rogues’ gallery often referred to as “the Grotesques.” Their collective homicidal methods include stabbing, shooting, immolation, and freezing people to death in refrigerator cars or scalding them in steam baths. To stop these evil-mutant types from taking over the world, Dick Tracy and his square-jawed fellow cops meet force with force, firepower with firepower. And they always, always win. As one newspaper editorial replied to complaints about the violence in Dick Tracy: “The sooner a child finds out what kind of world it is, the better he or she is equipped to get along in it.”

What children “learned” from early crime comics was that people with lots of money were at the endless mercy of people without any. From the time The Batman first appeared in Detective Comics in 1939, his enemies were, like Tracy’s, noted for their disfigurements—such as the Joker, Two-Face, and Clayface. And in a typical story, “crime” was something usually committed by people with nothing, against those with too much—often by means of jewel-thievery and house-breaking, or by robbing banks and trains. In The Batman’s first appearance, Commissioner Gordon enlists Bruce Wayne to investigate the murder of “old Lambert … at his mansion”; and “victims” of the next two issues include both the Van Smiths and the Vander Smiths. The Batman routinely hangs men outside high skyscraper windows or pummels them senseless in order to obtain confessions. No Miranda rights for these creeps. They were born bad and deserved everything they got.

Comic villains disputed the very idea of “civilization” with Tommy-gun bursts of animated nihilism—memorably dramatized by the Joker’s staccato “HA HA HA”s. Or, like Dr. Doom and Dr. Octopus, by devising diabolical scientific machinery for enslaving the world. As comics “evolved” over the next 50 years, these humanoid but deeply inhumane monsters grew only more irrational, sadistic, and destructive, slaughtering wider and wider swathes of humanity, until eventually the likes of Galactus and Thanatos were annihilating thousands, millions, and billions of sentient life forms at a time.

Jeremy Dauber’s American Comics: A History is an entertaining, big, and (sometimes

too) comprehensive survey of the comics industry, from its inception in early

twentieth-century newspapers to the latest Marvel Cinematic Universe megamovie

crossover empire. What quickly grows clear is how adroitly a simple format—sequences

of narrative panels, dialog bubbles, and a story line that might take many

months, years, or even decades to reach a conclusion—thrived in almost every

commercial medium that came along, spreading rapidly to magazines, radio, movie

serials, television, film, and games. But despite this facility to span media and

cultures, most comic books continued to dispense the same nonsense they started

with, depicting a universe in which people are defined by the brute exercise of

power. Not to mention the unbelievably exaggerated ways their bodies always

seem about to burst out of their Spandex.

It didn’t have to get so ugly. From the beginning, comics offered many bright alternatives to their own superhero nonsense, with a wide range of pleasing and still unusual comics, such as the surreal and anarchic dream-comedies, Little Nemo in Slumberland and George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, and later the lush, resplendent marvels of Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant, a series of panel illustrations thrumming with color and vitality that rivaled only Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon as one of the most beautiful Sunday color strips ever produced.

The first 16-page, book-length comics were assembled from daily sequences of popular strips like Mutt and Jeff and Foxy Grandpa; but soon the printing presses of New York were working overnight to produce some of the first regularly published comic books, notably The Funnies and Comic Monthly. As more books were produced, their readership grew, challenging the predominance of pulp magazines like Doc Savage at the newsstands and occupying restless children in the decades before TV.

It was probably due to the extraordinary success of The Shadow—about a masked crime-fighter sliding his way through New York’s mean streets—that comics began developing their own “costumed characters” (as they were originally called). The first of these, The Phantom, didn’t possess special strengths or powers but only the illusion of them. Wearing the purple costume passed down by his father and living in the same broody, candlelit cave, The Phantom’s special quality was an ability to pose as a white immortal watching over Africa like a strict but caring colonial parent.

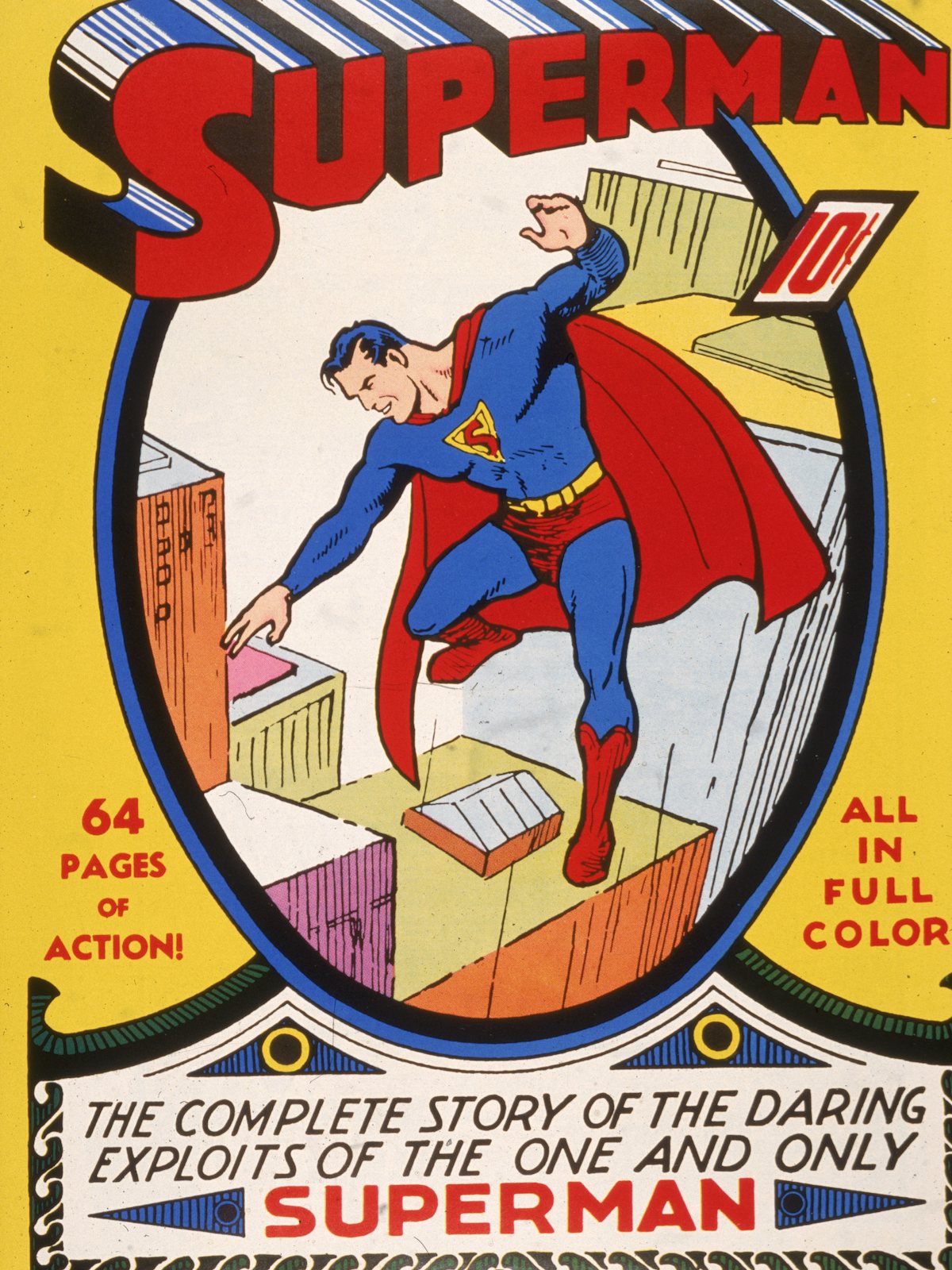

Only when Superman came along did the characters acquire superhuman powers. Drawn and written into existence by two teenage Jewish kids from Cleveland, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the original Superman script took several months to find a venue in the June 1938 issue of Action Comics. And when it finally appeared, it established three important notions in the marketing of superheroes: The super-character might well carry on super- dupering for many, many decades to come; the “origin” issue would eventually skyrocket in value; and the creators could sell all rights to their characters for as little as $130 and spend the rest of their lives in litigation. (Many years after creating Superman, Siegel was still writing for pay-per-page rates at DC, while Shuster was being arrested for vagrancy in Central Park and illustrating “kinky tales of adventure, bondage and torture” with characters that looked suspiciously like Jimmy and Lex Luthor.)

As Dauber argues, the “super-powers” were not on their own the secret of Superman’s success. What was more appealing was the idea that such powers might secretly reside in a clumsy, thickly bespectacled, blue-haired, all-round average guy like Clark Kent. Siegel himself later explained:

As a high school student … I had crushes on several attractive girls who either didn’t know I existed or didn’t care I existed. It occurred to me: What if I was real terrific? What if I had something special going for me, like jumping over buildings or throwing cars around, or something like that? Then maybe they would notice me.

Siegel had understood why young boys were so gripped by these colorful characters in their ridiculous costumes emblazoned with thunderbolts, hourglasses, and American flags—they knew what it felt like to be Clark Kent. But they wanted to imagine being somebody a lot better.

Dauber’s previous books concern Jewish comedy and the work of Sholem Aleichem, so it’s understandable why the early comics industry might attract him. From Harry Hershfield’s long-running Abie the Agent, about a Jewish car salesman who promoted the pleasures of assimilation, comics were, like the Hollywood movie industry, disproportionately owned and operated by young Jewish men—from Stan Lee (born Stanley Martin Leiber) and Jack Kirby (Jacob Kurtzberg) to Bill (Milton) Finger (Bob Kane’s collaborator on the creation of The Batman, who only received posthumous credit in 2015) and, perhaps most notably of all, Will Eisner, the most visually inventive comic writer, artist, and editor of his generation. Eisner may have best summed up the prevalence of Jewish talent in comics when he said: “There were Jews in this medium because it was a crap medium … it was an easy medium to get into.” Whatever the reason, it’s hard to consider the birth of commercial comic books without recognizing its deep debt to immigrant Jewish culture—a history that would eventually inspire Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (2000).

What these young, largely self-taught talents recognized was that living in America required submerging who you felt yourself to be in order to be accepted by a culture that increasingly respected obedience, repetition, and conformity. In such a country, everybody must have felt they harbored a secret identity.

Strangely, the fact that comics described an imaginary world presided over by violent masked vigilantes didn’t raise many eyebrows. What finally concerned psychologists and sociologists was the medium’s depictions of two cultural taboos that have always seemed especially worrisome to Americans: sex and death. In the 1950s, the great rogue publisher William Gaines caught the brunt of a crusade led by Dr. Fredric Wertham, whose influential 1954 indictment of comics, The Seduction of the Innocent, argued that superhero and horror comics were leading children “into nightmares, into anxieties, into moral confusion. The influence, however great or small, was never a good one.” He was especially concerned that some “comic panels contained hidden pictures of genitalia, which you could see if you squinted.”

In 1954, in an effort to stave off direct government oversight of their industry, comics publishers established a self-regulating body called the Comics Code Authority. Very soon, it proved to have a restraining effect on many comic artists and writers, and even brought many popular comic lines (especially the more violent ones) to an end. Of all the comic producers who would be put largely out of business by the Comic Code (“Respect for parents, the moral code, and for honorable behavior shall be fostered”), Gaines seemed the most personally offended. His favorite productions at EC, or Educational Comics, such as Vault of Horror and Tales From the Crypt, reveled in gross-out humor and depictions of a non-Manichaean world where the line between good and evil was hard to distinguish—if it existed at all. In these comics, bad men seemed to drive the engine of their own destruction; and the notion of “family values” dissolved in a view of humanity as a sex-obsessed, immoral jungle of wife-murderers and husband-stabbers. The gnarly old Crypt Keeper and his big, hungry cemetery were out there waiting for all of us.

EC comics, like Gaines’s later venture into humor publishing, Mad magazine, produced wildly comic caricatures of everything that was vain, foolish, and self-aggrandizing about American consumer culture; and they strenuously avoided presenting anything that looked like a “moral lesson.” (Except maybe this one: “Don’t be a total idiot like most people.”) And in retrospect, this refusal to moralize makes its comics sort of heroic. As Dauber writes, they “suggested a certain moral commonality with the monstrous.” One story about an abusive stepfather being run through a meat grinder was presented as “Grounds … for Horror!” and another, concerning a seller of bad meat who ends up displayed in his own butcher case, was captioned: “Taint the Meat, It’s the Humanity!”

While most comic publishers quickly fell in line behind the “Comic Code Authority,” Gaines defended his books before Senator Estes Kefauver’s committee investigating the influence of comics on juvenile delinquency and delivered possibly the most enjoyably rereadable testimony ever delivered to Congress—especially when he offered his opinion on the most “tasteful” way of displaying a severed human head on a comic cover.

The greatest strength (and problem) with comic books has got to be their almost octopus-like ability to grab onto any form of storytelling and make it theirs. They have thrived as pornography in cheap “Tijuana Bibles”; as educational materials in Classics Illustrated adaptations of Moby Dick; and as intro-level summaries of Heidegger and Foucault; as speculations on the Holocaust in Art Speigelman’s acclaimed Maus books; as multicultural autobiography in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006), Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000), and Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese (2006); and even as formidable muckraking exposés, such as Joel Andreas’s Addicted to War (which includes detailed footnotes and an index).

In fact, iterations of comic formats have spread so widely that it’s difficult to enter any home or bookstore in the world without encountering them. This has resulted in two qualities of comics that have both frustrated their creative development and intensified their production: Dauber describes these as “continuity exhaustion” and “brand expansionism.” And in today’s mega-conglomerate world, it’s hard to have one without the other.

“Continuity exhaustion” refers to the way some comics, after decades of serial publication, began carrying too much excess baggage. Characters had trouble jettisoning their outdated fashion sense, so they often appeared to be living in a 1940s time bubble; and the serial events of their story lines grew so complicated and contradictory that it was hard for readers (and writers) to keep up. For example, Jimmy Olsen’s career as a “cub reporter” started to look like a dead end after 50 years of nonadvancement; and after decades of flirtation, Lois still didn’t know how she felt about the two most important men in her life, Superman and Clark Kent, or understand why one of them always left a room just before the other one entered.

Then there was “brand expansionism,” leading the more successful comics (Batman, The Avengers, Spider-Man) to spin off characters into their own comics (Venom, Robin/Nightstalker, Hawkeye); and while the “crossover” potential of these interconnected story lines might boost sales, they also erected quandaries of plot complications. Meanwhile, the same villains endlessly came and went like shoppers in the Bloomingdale’s revolving door. It grew hard for the readers to keep up; and possibly even harder for the writers.

To break through these entanglements, the major chains began “restarting” their old comics and movie franchises over and over again. So fresh versions of baby Superman landed on Earth in the 1980s, the 1990s, and so on. Peter Parker kept getting bitten by that same radioactive spider—whether he was Tobey Maguire in 2000, or Andrew Garfield in 2012, or Tom Holland in 2017. And then various “limited series” comics appeared, set in alternate universes. In one, the entire Avengers cast became flesh-eating zombies. In another, Kal-El’s baby ship lands in Russia and he fights alongside his comrades against capitalist America. Familiar heroes were reimagined as old and wrinkly, as in The Dark Knight Rises and Batman: Year 100. Or as combatants in Elizabethan England. There were futuristic versions and MAX-rated adult-only versions and versions where they fought each other to the death in demolition-derby-style contests. But despite this overabundance of alternate universes, and the labyrinthine complications of the story lines, the only thing none of the major superheroes ever did was just finally die and go away. There was always some new embodiment, or some new film franchise, coming along to make them whole again.

At the height of comics expansionism in the early 1980s, Spidey and Superman began appearing on school lunch boxes, barbecue aprons, baseball caps, and computer mouse pads; they performed as bobble-headed sports team mascots and were developed into television shows, films, and even some Broadway musicals. (Sure, everybody remembers the disaster that was Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, but what about 1966’s It’s a Bird … It’s a Plane … It’s Superman?) Eventually, when turn-of-the-millennium CGI technology caught up with all that web-swinging and Hulk-smashing, the blockbuster movies arrived, and now nobody can make them stop.

Today our century-old comic culture is owned and operated by toy manufacturers and hedge fund billionaires—pretty much the same sort of people who own and operate everything else. And now that they know how to sell us all the same old crap we bought before, they will never stop selling it, and we will never stop buying it. The “eternal return” of comic book culture will continue presenting the “birth” and “rebirth” of the same superheroes until it’s impossible to tell one big “issue number one collectible!” from another.

For all its strengths, American Comics: A History often feels more like advocacy for the medium than an analysis of it. Many pages are filled with quick synopses and appraisals of notable comics that came along over the last hundred years, along with reflections on how the once-family-owned companies that invented comics were eventually subsumed by megagiants. At times, reading Dauber’s warm, appreciative comments on everything from Neil Gaiman’s Sandman to Moebius’s Heavy Metal feels like strolling through Roger Angell’s essays on baseball, where every game in the sun is entangled with the memory of every other game ever played in a sort of eternal blissful childhood of sunny bleachers and savory, dripping hotdogs.

But comics are a more duplicitous and all-devouring game than baseball. They have climbed up out of every venue they conquered and oozed into our shopping plazas and schools, infecting our national conversations and body politic, and even emblazoned themselves across the fuselages of death-dispensing tanks and planes. Comics—the commercial, corporate-owned and multi-commodifiable ones—have affected the way Americans, and other nations, think about America to a degree that may be far more destructive than any ideology. They reinforce the idea that power is the greatest thing we can imagine for ourselves; that the “bad guys” are unregenerate serial predators who need to be locked up so deep they won’t ever be seen again; and that the “best” person wins only if they bring the most weaponry to the game.

There have been many genuine pleasures in comic books over the decades, from the pure narrative joy of Carl Barks’s Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge to Robert Crumb and Harvey Pekar’s minimalist tales of untidy, barely-middle-class sadnesses in American Splendor. And yet corporate greed has commodified the superhero metaphysic until it permeates almost every inch of our lives with visions of irredeemable urban decay. Meanwhile, the signposts of decay have hardly changed at all—rainy neon XXX-rated porn theaters and homeless people standing around flaming garbage bins to keep warm—just the sorts of places where no sensible culture would want to see masked vigilante superheroes running around kicking ass.