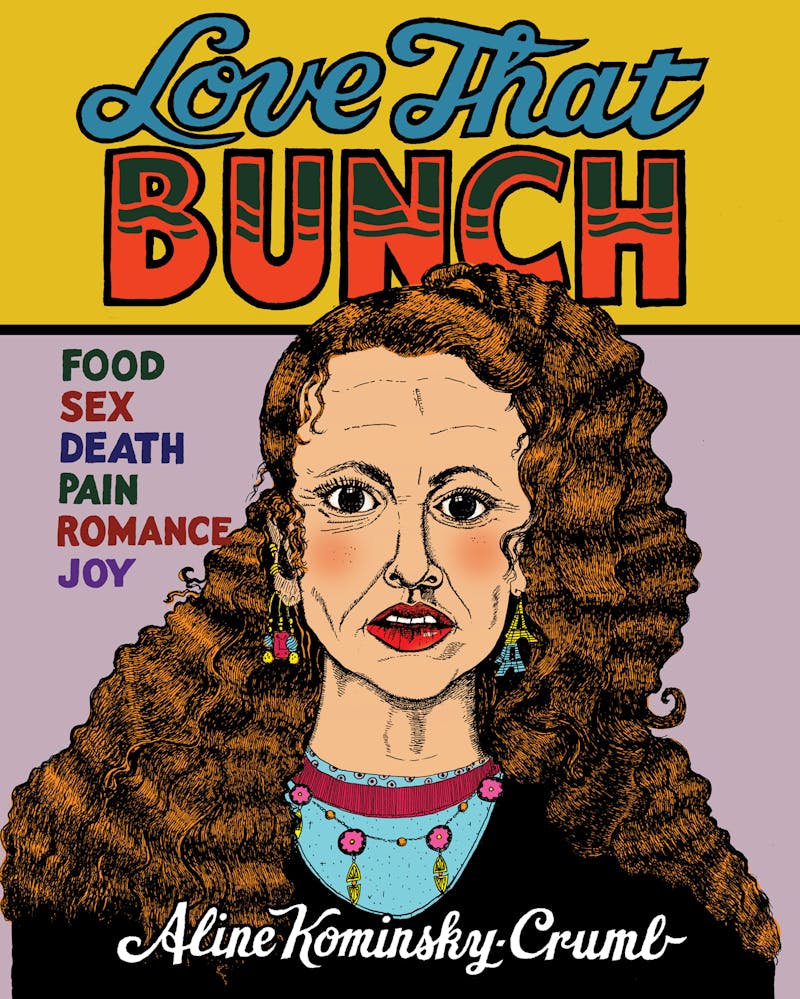

Aline Kominsky-Crumb has been an underground comics hero for a very long time, but only recently has she started to receive her proper due. Last year, David Zwirner Gallery exhibited a large selection of her work, along with art by her husband, R. Crumb. Now, Drawn & Quarterly is publishing a definitive collection of Kominsky-Crumb’s work, Love That Bunch. Borrowing unapologetically from life, Kominsky-Crumb draws with a line that is unmistakably her own. She sat down with me to talk about her influences, her art, feminism, and more.

Were you a big comics nerd as a kid?

No, not at all. My parents were very pretentious and upward-striving. They made me do ballet, and tennis, and horseback riding. They wanted to make someone that a Jewish orthodontist would want to marry. Real class. So they didn’t like us to read comics, but I used to watch old cartoons on Saturday morning TV. I really liked Little Lulu, because she was this tough girl. They’d say, “This is the boy’s clubhouse, you can’t come in!” But she always found a way to get in there.

But I wasn’t a comics nerd at all: My comedy comes from stand-up in New York. My grandfather was a huge wannabe comedian, and he took me to see every comic in New York: Jackie Mason, Alan King, Henny Youngman, Don Rickles. My humor is directly related to that in terms of storytelling: self-deprecating, self-referential, very autobiographical stuff about the family, about daily life, that sort of thing. Also Joan Rivers, Phyllis Diller: They were the only two women comics that I was interested in, so my work comes out of that.

I’ve also been a painter since I was 8 years old. I went to Cooper Union, I got a degree in art, so my work also comes from a fine art background. I was very influenced by German Expressionist art—art of pain and agony. Put those two things together and that’s what my work is really about.

What about influences?

The first artist I went towards was Justin Green. His book Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary influenced me more than anything. It’s the first autobiographical comic ever done, as far as I know, and mine was the second. I was the first woman to do that.

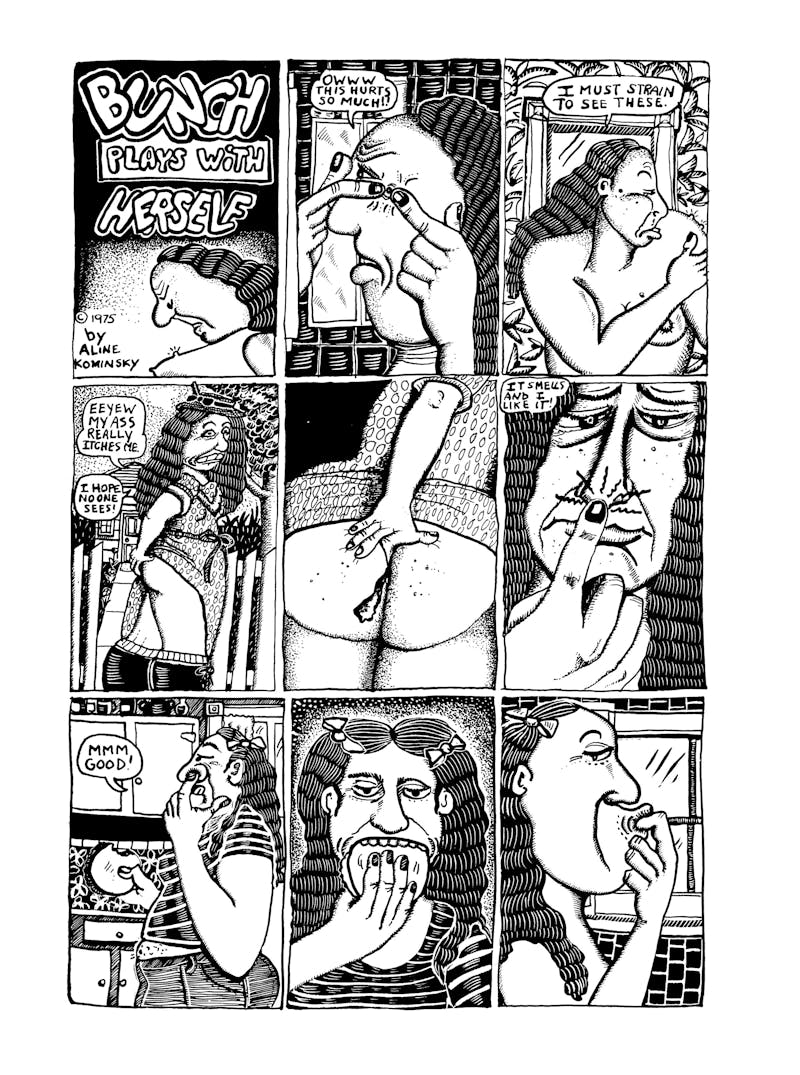

Women at that time—in the early 70s—were very militant feminists, and there wasn’t a lot of humor. They thought my work was too self-deprecating and they didn’t like it. They made stories where they turned themselves or their female characters into superheroes, because they were big comics fans, they came out of a comics background. They were romanticizing women and trying to make women powerful and empower them. I understand that, too. But my work was too ... I showed myself being raunchy, wanting to have sex with men, and being a bad girl and taking drugs.

So you and your coterie were locating strength in two totally different approaches to being vulnerable. One approach is, “Lets act like there’s no vulnerability, let’s be tough.” And then there’s the tradition of New York humor: If you are eloquent and funny and insightful about your vulnerabilities, then you gain a kind of mastery over them.

Yeah. Also, if as a woman you can be really gross and really throw it all out there, it’s very rebellious. I drew myself on the toilet on the cover of a comic book. I like it, but women thought that was degrading.

To acknowledge that we exist in the world as bodies?

Well, don’t ask me! But we split up. The other bad women and I went in one direction, and we became Twisted Sisters, and the other group went on to be Wimmen’s Comix. There was a humor impairment there for me; that was the problem. I didn’t think those women had a good sense of humor. This was the first time where I felt like I was really out of Long Island and away from my family, and really living a life that I always imagined was possible. I had tons of boyfriends, I didn’t want to settle down, I was completely wild and I was having fun and I didn’t want anything to hold that back.

Earlier in your career you didn’t get your due. Now you have this big old book, and legions of fans (like me!). That must feel kind of strange. Or—how does it feel?

It feels really good actually! One reason is that young women are doing some great stuff now. When I saw Lena Dunham put herself on the toilet on TV, I fell out of the chair, because I wondered if she’d seen my comic. I wonder if I influenced that. So I see that it has filtered down into the culture of women’s expressiveness.

Also, a lot of great comic artists like Alison Bechdel, Phoebe Gloeckner—all of those women were influenced by me, and that’s so satisfying. What more can you ask for? Now, I’m the great-grandmother among young comics.

But I didn’t set out to do anything. I was just an artist, and the work that I did came out of pain and anger, and it was my way of dealing with my horrible family. I didn’t set out to do anything revolutionary or create a style or be a groundbreaker at all. I only know how to write about my life. That’s it.

You went out to Arizona to finish art school, right?

Yeah. I was at Cooper Union here, but then I got mugged like three times because I lived on the Lower East Side and it was so dangerous back then. I finished my fine art degree at the University of Arizona.

There’s this one panel that’s in the book, where you are looking at a painting in a gallery and you’re thinking: If I can figure out how to do this, I can get out of Long Island. That made me think about status, and the line between fine art and commercial art. Is that a tension that has bugged you over the years?

I don’t think about that kind of stuff at all. You have to realize that I left New York 50 years ago: I’ve lived in the country, in the sticks, away from anything. I live in a small village in the mountains in the south of France, so most of the time I don’t even think about that shit.

You know, I’m an artist, I just work. I don’t make much money. Fortunately my husband does. His work is very valuable, so we are able to live.

Actually one of the first pieces I wrote for The New Republic in my current job was about the show at David Zwirner last year.

You wrote that? It was good!

You saw a lot of my paintings there, they sort of mixed it all together and did such a good job of hanging it. I had just finished a really long story for this book and I had sent it to them three days before I arrived. When I came to the gallery the day before the show they were hanging it. They gave the story its own room, and it made me cry. I was so touched, so happy. Such a great gallery.

Coming from New York and having pooh-poohed the whole fine arts scene there, and then ending up at that gallery ... it was the ultimate. It was an indication of everything in a way—the fact that I gave it all up, went away 50 years ago, didn’t care—and then I end up there. I have to say that it was deeply satisfying.

Are you one of those people that sits down and sketches out the structure of a whole page, or are you more the type that starts at the top of the piece of paper with no plan?

I always have a seed of an idea. I use the story as a guise to say something; I usually have a deeper purpose in my story. It’s like a rant, a critique or whatever. I have lots of stories written in my notebook, but the ones that speak to me and the ones that make me tell them—there’s something in there that I really need to stay. Then the story sort of arranges itself as I go. I don’t know where it’s going to go exactly, always.

Do you sit and think up your punchlines beforehand?

No, but I’m really funny in real life. But then I don’t remember most of the things I say, so when I sit down my mind is completely blank and then what pops out, pops out. Robert will say, “Too bad you told that story, you should do it as a comic!” Then I’m like, “Well, I just told it to you. It’s gone.”

When Robert and I worked together for The New Yorker we were obliged to plan things more. It was much tighter form because you had only three pages, you couldn’t say fuck and you couldn’t write sex. On the other hand, we kind of liked the strictness too. They would put us in ridiculous situations and ask us to be journalists and stuff like that. It had to make sense—it had to be accepted by them—but they never rejected a story that we gave them.

They have a great new cartoon editor over there now.

Well, I don’t work for them anymore. Robert got kind of on the outs with them. He doesn’t really want to work that much anymore, for anybody. Robert is through with public life, because he got famous very young and it really fucked him up.

He was such a nerdy guy in high school. No girl would ever look at him. He was miserable. His teeth got knocked out when he was 15 years old, so he went through high school with no front teeth. Big glasses, very skinny. He was miserable. But then he was the man of the hour; Janis Joplin’s groupies want to fuck him. Artistically it kind of screwed him up and then people ripped him off so much. He was really bad at business. Anyway, it all turned out ok. We’re successful enough.

Is Bunch a character? What kind of relationship do you have with her?

Yeah, she’s a character. I reveal what I choose to reveal. A lot of it is me, a lot about her is true, but I pick and choose so I think it’s a character. I’m fond of the characters. I think in old age I’m much kinder and gentler. Bunch has been with me for a long time so I feel an attachment to her.

Have you ever felt constrained by the works you’ve done in the past and wanted to change things up?

Neither. Not super happy nor constrained, just I really don’t feel in control. What comes out just comes out. It just hasn’t changed that much; over time, my voice has stayed fairly consistent, amazingly. I don’t know if I’m stable, but I’m authentic. I think some of my early work is a little bit extreme and out there. I think life is less like that now, but I don’t know. I just recently did Of What Use is an Old Bunch? which is pretty raunchy! It’s not that different in sentiment from the first story I did. There’s a part of me that’s stayed true to that self ever since.

When I see people that I once knew years ago, there’s some of them that I can’t even recognize. Some are still them, just older. I feel that I am still myself, just older. The thread is still very clear.

Are there any favorite things that they left out in the book?

No. They put everything into the book that they could find copies of that they could print! My stuff was very obscure and I don’t have all the original artwork, so it was a case of what they could get. They did such a great production of it; it was a pleasure to work with them. Some of those stories were printed very light or too dark in other versions, so they corrected everything and evened it out so it’s very readable.

It’s very emotionally heavy for me to read all the old stuff, so I haven’t sat down and read the whole thing yet. But I’m going to.

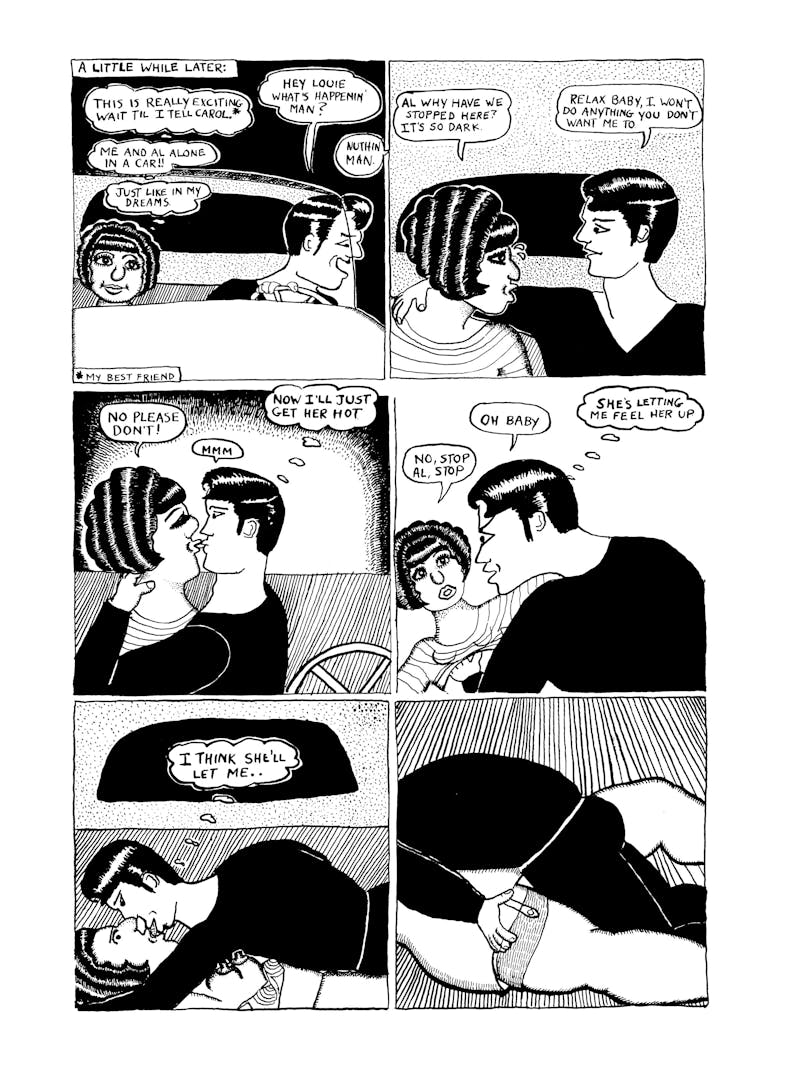

A lot of the stuff from when you were young, when you talk about your family and some of the sexual experiences … it’s really heavy.

A lot of people have said to me, “That first story is about a rape.” And I had to say, well, it’s interesting you say that, because it wasn’t that to me. The guy was a cad and he dated me for a year just to have sex with me, and he did that serially. I didn’t realize it but I was madly in love with him. It was the most painful thing that I ever experienced emotionally, and my heart was broken, but I was so hot for him! I wanted to have sex with him. It was deeply fulfilling for me, but the next day he broke up with me. That was emotional rape. It wasn’t physical rape at all.

I think we are in this moment where people are trying to draw very big, clear lines, which is good, because it’s going to protect people. But it does mean flattening out a lot of the intricacies of experience.

Yes. The forbidden bad boy was totally what I wanted. I still think that the build-up to that was the ultimate erotic experience. Then the ultimate cruelty.

Having multiple selves, all kind of exploded out in your work, you get to give a literal voice to conflicting feelings. One part of me wants this, one part of me doesn’t. One part of me hates the other part of my self.

That’s so often the real situation. There’s abuse of power and there’s crime, and then there’s also ambivalent sex play between people that is very, very difficult to maneuver around. So many things. I think what’s inexcusable is the abuse of power.

I’m a real hard-ass about this stuff because I was a teacher for so long, teaching college kids, and I knew so many dudes who would sleep with their students.

That’s why I didn’t become a professor. I was offered a teaching position in the art department [in Arizona], and I was going to do it. I was debating between moving to San Francisco and drawing comics or doing that, which would have been a wiser career move in certain ways, in terms of making money and having stability. But I saw all my teachers and they were all alcoholics, they were all fucking these young students and I was like, “What am I going to be? I’m already an alcoholic!” I just saw a sordid future for myself if I stayed there.

Actually the thing I always felt bad about was that they always had amazing wives, and even in front of the wives I fucked the husbands, which was stupid, but whatever.

You can’t blame your younger self.

That’s the one thing I regret. But you can’t have regrets about that, because I did have fun and it did propel me to San Francisco to draw comics. I made the right choice. I went with the adventurous, insecure choice. And that was a good decision for me.

In New York people stay in this sort of extended adolescence, where they just act like college kids forever.

I stayed in adolescence until I was 50. I consider 50 when I got over adolescence.

I never wanted to get married and have kids and yet, I’ve been with the same man since I was 23. We always had a flexible relationship, we let each other grow and move on in life. We had such a deep, spiritual bond, right from the beginning, there was something really deep between us. I don’t like to put this into words, but we both kind of knew that there was something there and we could stand each other on a day-to-day basis.

It’s very unusual. The whole thing is very unusual.

I still like living with Robert very much. We have a big house; we don’t see each other that much. He stays up until 5 in the morning, I get up at 7 in the morning. We have about two hours in bed together, so it doesn’t give us much time to do much. And you know, I come home from teaching yoga and have giant salad and some squid and some weird thing and he’s having bread and butter and jam. He sleeps in the morning and he stays up late. We’re like ships passing.

Do you think that’s what makes it work so well?

For me, yeah—I couldn’t be in traditional marriage at all. Not at all. I thought being a mother was very difficult, very painful. I had some postpartum problems, that’s when I went into deep therapy because of the pain caused by being a mother and loving this child so much that instead of being happy it felt painful. I thought, why can’t I just feel happy? And that propelled me to really work on myself some more.

It’s very complicated. Having grandchildren is totally fun because you don’t have that neurotic aspect. I get along with my daughter really well now; she’s this great person that I admire. She admires me, too. You know, we don’t have a cultural gap like I do with my mother. We like a lot of the same things, although taste-wise she’s completely understated and doesn’t like color. She likes simple environments and I live in the kitsch palace. Look at me! I’m like a Christmas tree.

You’re in such good shape, and super health-conscious. How do I square that with your work, which is not about being perfect?

I was a wild, out-of-control person, but I gradually got it together. I gradually got healthier, partially from expressing my anger and pain in my work and partially from therapy and partially from yoga. All of those things, and having kids, and being loved by one man for almost 50 years—all those things make you get better and make you get it together. All of that. I started out as such an out-of-control, self-destructive human being.

When I look back at pictures, when I thought I was ugly—I was beautiful! It’s so sad that I didn’t appreciate it then. I was gorgeous and I felt so ugly and I think that is such a sad thing, you know. I actually feel more attractive now at my age than I did then.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.