Every year, on the first Monday of October, the Supreme Court begins its annual term. Every year, around that time, court watchers predict to varying degrees that it will be a blockbuster term; the most pivotal period in the high court’s history. Here’s the thing: They are almost always right. The Supreme Court plays a major role in deciding (or effectively deciding) many of the major political and legal questions of the day. So it’s almost a cliché at this point to say that the 2021–2022 term will be a highly consequential one as well.

As the remainder of the court’s term unfolds in 2022, it will matter how the justices decide high-profile cases on abortion, gun rights, public health, and more. But over the long term, the coalitions that emerge out of those decisions will be important signals for future cases that come before the court.

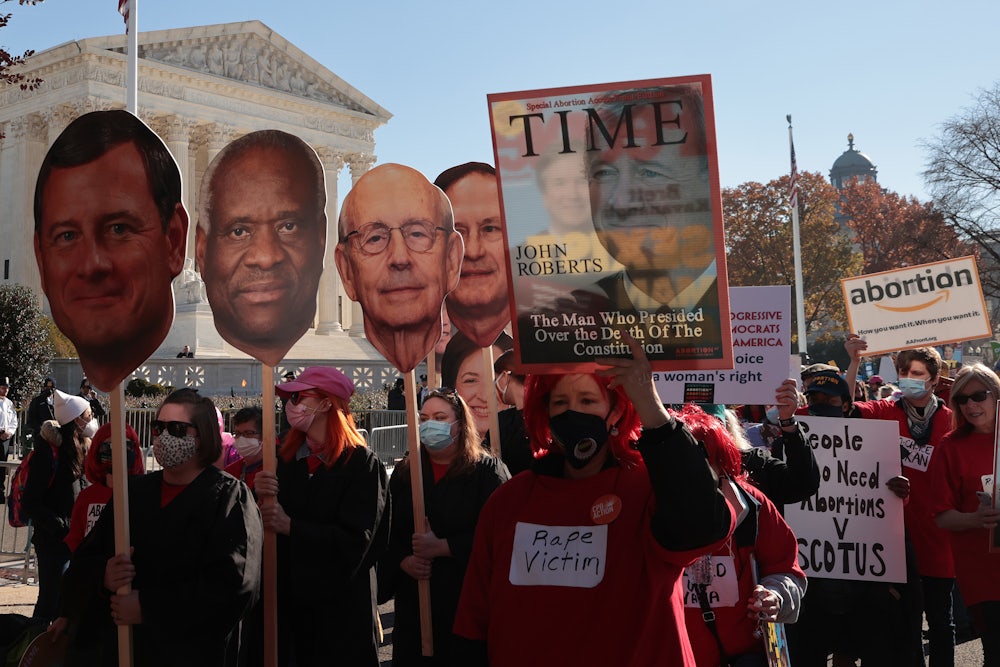

At the forefront of the docket this term are abortion rights. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the justices are squarely considering a Mississippi law that bans the procedure after 15 weeks of gestation—a direct challenge to Roe v. Wade. Five of the six conservative justices, excluding Chief Justice John Roberts, appeared ready at oral arguments to overturn Roe. Roberts’ questions suggested that he might favor a narrower ruling that gives states more power to restrict abortion without overturning Roe entirely. But there did not appear to be any takers among his conservative colleagues during the high-profile session.

If Roe is overturned, there will be swift consequences. The New York Times estimated last week that legislatures in at least 22 states would move to either ban or virtually ban abortion as quickly as possible. Other states would likely see major political clashes on the subject; only a few explicitly protect abortion rights under current state law. The court gave Americans a taste of the new frontier earlier this month when it decided Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson. Though the court left open a narrow lane for Texas abortion providers to challenge the state’s controversial bounty law in federal court, it also refused to block the law from being enforced while litigation continues. Coupled with the likely outcome of Dobbs next spring or summer, the Roe v. Wade era may already be over in Texas.

Naturally, nothing that happens at the Supreme Court is final until the justices release a decision to the public. Some anti-abortion activists still fear a repeat of the 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, when Former Justice Anthony Kennedy initially provided the fifth vote to strike down Roe after oral arguments, then changed his mind and co-wrote a compromise ruling that kept abortion rights mostly intact for another three decades. Abortion-rights groups, by comparison, largely expect the worst now that Kennedy and Ruth Bader Ginsburg have been replaced by Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

Abortion isn’t the only conservative policy priority before the court this term. In New York State Rifle and Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, the court’s conservative justices look ready to strike down the Empire State’s strict limits on concealed-carry permits on the grounds that they violate the Second Amendment. The ruling will end a decade-long drought on gun-rights rulings at the high court, one apparently driven by Roberts’ unwillingness to hear cases involving gun restrictions. Justice Clarence Thomas, subtweeting at least some of his colleagues in recent years, complained that his colleagues were treating the individual right to bear arms as a “second-class right.” A key issue in Bruen is just how much leeway state and local governments should receive when crafting gun-related restrictions. If the majority opts for strict scrutiny, the most grueling hurdle for governments to overcome, then a wave of other gun-related restrictions could also be imperiled.

There are signs that Roberts’ influence—and his less combative form of conservative legal thinking—isn’t completely spent. Since this summer, for instance, the court has declined multiple opportunities to block state and local public health officials from issuing vaccine mandates. Justices Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch signaled in public dissents over the last few months that they would be willing to enjoin those mandates on religious-freedom grounds in some cases. But they appear to have been outvoted by Roberts, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and the court’s three liberals in every instance so far. That 3-3-3 coalition will almost certainly be tested in the months ahead as right-wing litigants bring legal challenges against the Biden administration’s testing mandate for most major employers.

But the court is still poised to potentially deliver crushing blows to other progressive policy aspirations. In late October, the Supreme Court announced that it would hear West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, a case that could have major implications for U.S. climate policy. The lawsuit, brought by a group of Republican-led states, asks the court to sharply narrow a provision of the Clean Air Act that the EPA has used to regulate carbon emissions. If the court rules that the EPA went too far, it would fall to Congress to pass new legislation to give the agency that power—and if it doesn’t, the U.S. could find it impossible to meet its commitments on reducing carbon emissions. The implications for international efforts to limit climate change’s impact would be seismic.

It’s not too late for the court to add new cases to its docket this term, either. Two closely watched petitions involve the use of race and diversity in college admissions. Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College is a Title VI challenge against Harvard University for allegedly penalizing Asian American applicants in its admissions process. A companion case involving the University of North Carolina raises similar points against a public university. The organization named in both cases was founded by Edward Blum, a legal activist who targets laws and policies that help racial minorities. His greatest victory to date was in Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, where the Supreme Court shattered a keystone provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Both lawsuits ask the court to overturn a line of Supreme Court cases that allow colleges to consider race and diversity during the application process. Their primary target is Grutter v. Bollinger. In that decision in 2003, the court ruled that a student admissions process that ensured a “critical mass” of students from “underrepresented” communities would enter the University of Michigan’s law school did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. Former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who authored the court’s opinion, suggested that the policy might no longer be needed in 25 years. The court’s current conservative bloc, however, might be more willing to move up the timeline and strike down affirmative-action programs more broadly.

When the court closed out its 2019-2020 term last year, Roberts appeared firmly in control of the court’s direction. The chief justice often used his swing vote to compel the court’s four liberals and four conservatives to hand down narrower rulings on hotly contested issues. But Ginsburg’s death last September, and Barrett’s subsequent ascension, upended that finely wrought balancing act. After spending the last term digesting the court’s sudden ideological shift, the conservative justices now have an opportunity to decide where they will go, what they will use to get there, and how quickly they will travel along the way.

What are the practical consequences? By this time next year, Americans could live in a country where legal access to abortion has vanished in half of the states, where concealed-carry requirements for firearms are broadly loosened, where colleges and universities can no longer consider diversity in their admissions process, and where the Environmental Protection Agency can’t regulate carbon emissions. Much of 2022’s political attention will revolve around the November midterms, when Americans will vote in hundreds of House races and elect one-third of the Senate. Nine of those Americans will also be voting next year on the country’s future—and their ballots will count a lot more.