You can sense Robert Caro’s disappointment after he asks a group of CUNY Newmark Graduate School journalism students if they’ve seen a typewriter before and nearly every hand shoots up. The typewriter he is standing over is a Smith Corona Electra 210, a model practically synonymous with him. It is—no surprise—no longer being made. Caro has several backups, which he scavenges for parts, but is down to 10. If, that is, you don’t count the one that has now become a museum display and, at the same time, a kind of metaphor for Caro himself.

The typewriter also marks Caro’s first lesson to the 20-odd graduate students who are crowded around him. Caro, the most influential biographer of the last century, is leading them through selections from his archive, which has recently gone up as an exhibition at the New York Historical Society. It is likely the first permanent public exhibition of an archive devoted to a living author in the country. (Everyone, it should be noted, was vaccinated and masked except for Caro—his bifocals fog up—and this was late October, before omicron.)

“People ask me why my books take so long,” Caro said. “I’m very fast. When I was at Newsday, I was on the rewrite desk—I was the fastest rewrite guy,” he said barely disguising the hint of pride.

But when it came to writing books, he recalled a piece of advice from an old creative writing professor at Princeton, R.P. Blackmur, a poet and critic perhaps best remembered now for being parodied by Saul Bellow in Humboldt’s Gift.

“Mr. Caro,” Blackmur told him, “you’re never going to achieve what you want to achieve if you don’t stop thinking with your fingers.” And so Caro endeavored to slow down by whatever means necessary. “I write my first draft in longhand,” he continues. “Sometimes many first drafts. And then I go to a typewriter, and I use a typewriter instead of a computer basically because a typewriter is slower.” He continues making revisions through the entire publishing process, not just in galleys but in page proofs, something that’s practically unheard of. (“He breaks all the rules,” jokes Paul Bogaards, a Knopf publicity executive who has worked with Caro for more than 30 years.)

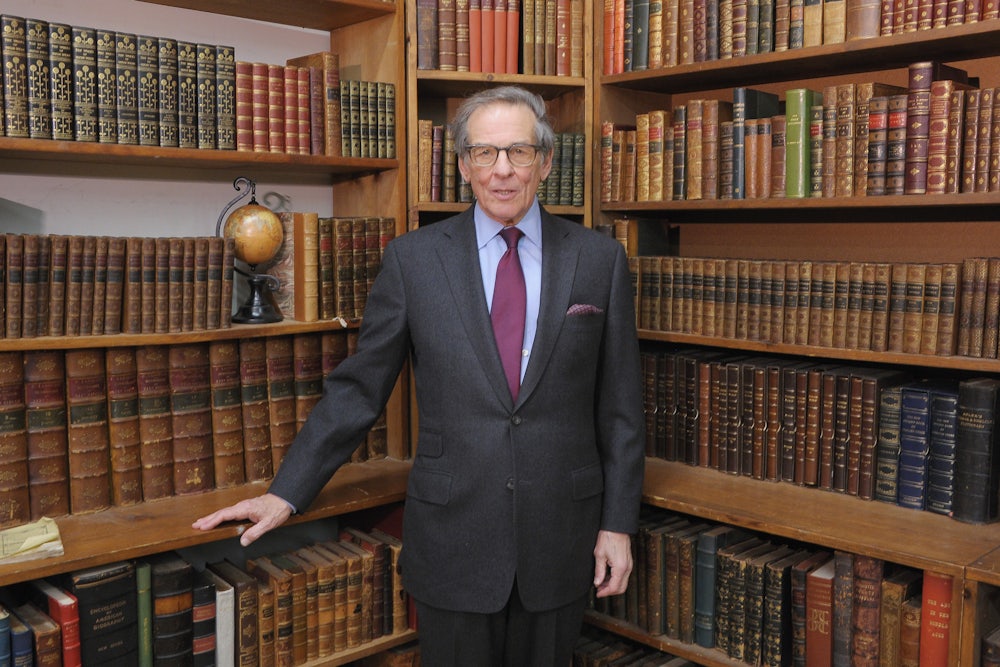

Dressed casually (at least by his standards) in a red sweater and suit but no tie—he famously writes from home in a full suit, an anomaly in the ubiquity of Covid-era casual work-from-home attire—Caro is, in some ways, an odd choice as a mentor to journalism students in the 2020s. (Caro, who hasn’t worked on a news desk since the late 1950s, is also mortified by the challenges facing young journalists in digital newsrooms. Asked in a 2019 Gothamist interview about Chartbeat, the analytics tool that tracks, among other things, page views and engagement time on articles, Caro joked that it was “the worst thing” he had ever heard of.)

Although Caro is among the most influential nonfiction writers of the last century, his mammoth biographies of the shadowy New York kingpin Robert Moses and President Lyndon Johnson are, in many ways, throwbacks. They’re immense, covering ground that few, if any authors, are allowed to attempt today. The Power Broker, his book about Moses, comes in at over 1,200 pages, while there are currently four volumes in his biography of Johnson, spanning thousands of pages covering the thirty-sixth president from his birth until 1964. He is currently at work on a fifth volume, which is expected to cover Johnson’s legislative accomplishments during his first full term as president, as well as his escalation of the Vietnam War. The books themselves resemble, as much as anything, the totemic novels of the midcentury.

But Caro’s great subject—power—and his approach to journalism are as pertinent and vital here in the young years of this century as is the close, empathetic attention he pays toward those who become caught in the crosshairs of the powerful.

He takes care to point out a steno notebook that he and his wife, Ina—a name that Caro pronounces with an r, in a New York accent that is, sadly, swiftly vanishing—used to track the racial demographics of Jones Beach–goers. Caro had discovered that Moses had purposefully built the bridges over New York’s parkways too low to ensure that buses couldn’t take inner city residents to the beaches of Long Island but wanted to prove it. He made three columns—for white beachgoers, Black beachgoers, and Hispanic beachgoers—with whites overwhelmingly in the majority.

“I’ll never forget seeing this and thinking you could institutionalize racism with concrete,” he said. It’s a moving image but also a move that sums up Caro’s holistic, dogged approach to journalism: You find something researching and go out into the world to make sure it’s true. He deservedly has a reputation as a lion of the literary world of the last century—and the way he writes about the Texas Hill Country that Johnson was raised in is as vivid and distinct as anything in American literature—but the Newsday reporter is still there.

Asked if he has a word count he tries to reach each day, he laughs and gestures toward another notebook in the archive. He aims to write 1,000 words a day. On the days he didn’t hit the mark you can see, faintly, one word written and often underlined: “lazy.” But much of the archive and Caro’s lessons to the students reflect his determination. In 2019, he published Working, a book that could be considered a companion to the New York Historical Society exhibition itself, which covers much of the same ground. Working is, in many ways, a journalism school in and of itself, a document of a dogged reporter whose triumphs are nearly always hard won. One anecdote, for instance, recalls the effort that Caro and his wife expended in an attempt to track down a classmate of Johnson’s, their only clues to his whereabouts being that he had moved to a town in Florida, “north of Miami,” with “beach” in its name. Naturally, they found him.

But so much of what Caro talks to the students about is about how to find something even richer: a sense of place. When he first visited the remote Texas Hill Country, he came to a swift realization: “I’m not understanding these people, and therefore I’m not understanding Lyndon Johnson.” And so he made a decision: He and his wife would move there. (“Why couldn’t you write a book about Napoleon?” he remembers Ina, who has written several books about French history, saying to him.)

He had, until that point, spent most of his life in New York City—with a stint at Princeton and another in Boston as a Nieman fellow. “Everything about the poverty of that area … was so unbelievable to me, a city boy,” he said. This was half a century ago, but there is still wonder in his voice. The women were stooped—in the Hill Country they call it “bent”— from carrying buckets of water drawn from wells 75 feet deep for decades. Eventually, Caro got it: “That was Lyndon Johnson’s world. A lot of things that people didn’t understand about Lyndon Johnson become very clear if you just learn about the place where he grew up.” All it took was moving to remote central Texas.

The doggedness is built into his approach to writing, as well. Asked if he ever gets stuck, he does a performative eye roll—“Well, yeah!” But, he says, he tries to get stuck in the outline. “I can’t write a book until I see the whole book,” he says. “You try to do all the research before you ever start writing. I try to see the whole book right down to the last line before I start writing. What I do is I put up an outline, it’s on a corkboard. The corkboard is about 22 feet long.” This is how the Johnson books are composed: First on corkboard, then on a notepad, then typed, and then, after thousands of revisions big and small, published at last.

But one thing has remained the same, Caro tells the students, “I started as a journalist. Now I suppose I’m called a historian. For me, I’ve been doing the same thing all my life. The techniques I use to find out things for my books are the same techniques I learned as an investigative reporter.” His archive at the New York Historical Society is as much a monument to how a life-altering devotion to the writing process itself is perhaps more precious than any published work.