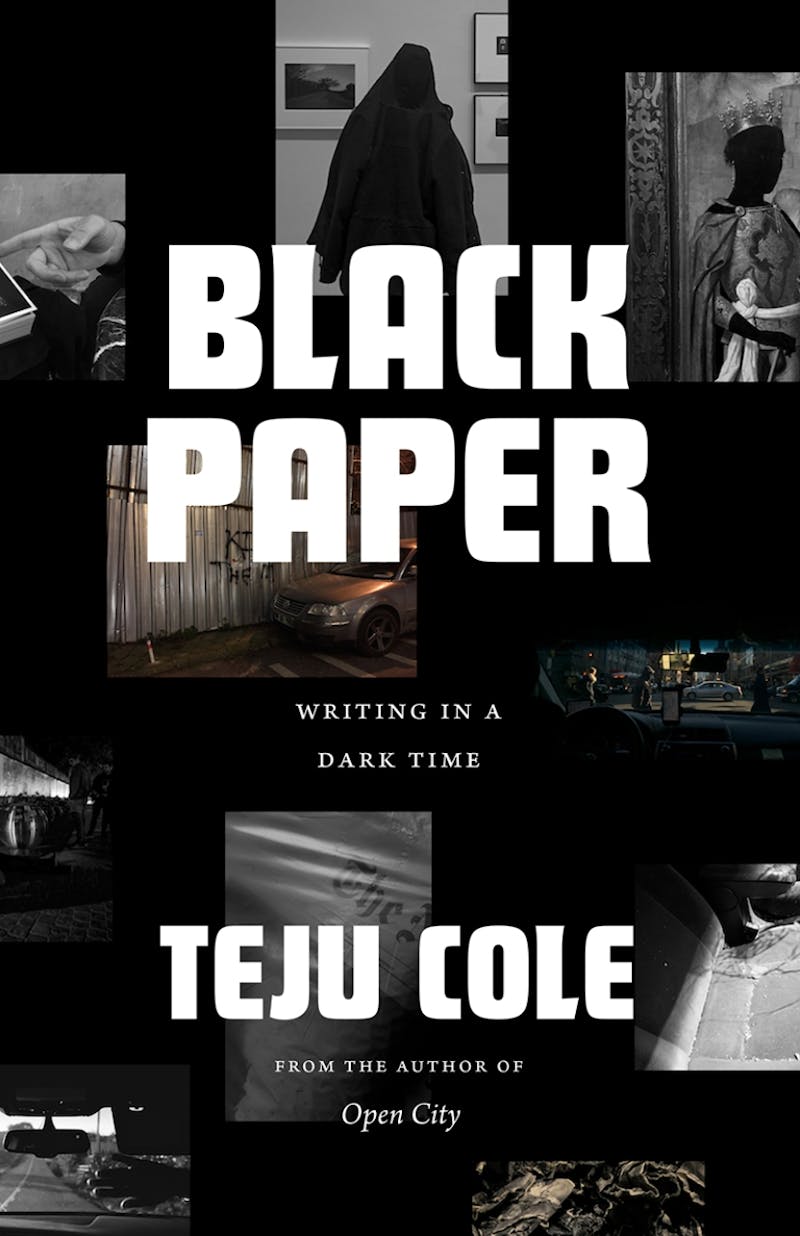

Each thing has its shadow: the name of the baroque painter Caravaggio, which reads “like two words conjoined”—the painterly technique of chiaroscuro and braggadocio, or boastfulness; the Danish philosopher Ludvig Holberg and the slave ships he invested in; Rilke’s famous poem about a caged panther and his less-known, startlingly racist verses about caged Ashanti people. In his new essay collection Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time, the Nigerian American novelist and critic Teju Cole explores the flickering of light and shadow in photography, classical music, painting, and literature, and applies the same theme to elegies for departed friends, artists, and intellectuals, and the kind of rambling but penetrating meditations on cities that have characterized his novels.

Largely focused on photography (Cole is a photographer himself and frequent photography critic), these essays also encompass migration, the history of slavery, Trump’s presidency, “African” as an identity, and the movie Black Panther. Cole often goes to places where the conventional connotations of light and dark reverse: the harsh, cheapening, glare of photography, for instance, in moments when the camera is unwelcome or the instant he discovers the Sesotho word serithi, which can mean “shadow” but also “aura,” “dignity,” “presence,” or “confidence.” The word black, with all its shades and connotations, provides a through line in what might otherwise be an impossibly abstract conceit for a book. The title refers to the making of carbon copies, where “black transported the meaning” from page to page; Cole is intent on finding meaning in the dark. These things shadow Cole’s work: the exclusion of people from nations and from personhood and the sense that art cannot possibly do enough. What lights his way is his certainty that, on occasion, it can.

The strongest arguments in the book are found in essays that Cole originally wrote for The New York Times Magazine. He takes up Susan Sontag’s question of what good can come from regarding the pain of others and focuses it on migration, that realm of human suffering that has perhaps replaced war as the source of the most iconic, tragic photos of the contemporary era. And while much photography about migration, like war, intends “to depict the suffering of people ‘out there’ for the viewing of those ‘back home,’” Cole argues that the intended audience for such photos is directly implicated in the policies that keep people out.

Several essays make the case that certain photos do not need to be seen. The “kinship of photography and violence” is evident in the verb to shoot, in photography’s role in colonialism, scientific racism, and surveillance, and in the double standards of newsworthiness and decorum that apply to journalistic images of dead bodies of different races. Context is key for Cole, as it was for Sontag: A photo of women in Nicaragua gasping at the stench of dead bodies in the street is just a picture, however moving, of “the universality of grief,” unless it can inspire investigations into the politics and history behind it. The policies that led to the famous photo of a father and daughter drowned in the Rio Grande might be better, less spectacularly, illustrated by “a president, a member of Congress, a Border Patrol agent, a lobbyist, a judge.” In considering photos of migrants in refugee camps in Europe, Cole is drawn to the work of Richard Mosse, panoramic images made with military-grade thermal cameras, which he thinks succeed in “evoking racial horror rather than prettily displaying it.”

Cole acknowledges that a project like Mosse’s risks becoming a mere aestheticization of the problem. There is no guarantee that people will see those anonymous heat signatures as a reflection of the inhumanity of their own society any more than they will when viewing work that still grasps at the bare-minimum goal of “humanizing” the other’s plight. Still, it is easy to agree with Cole’s contention that the comfortable owe the afflicted “a measure of privacy.” As he writes: “Among the human rights is the right to remain obscure, unseen, and dark.”

When he expresses skepticism about the power of an image depicting pain to change policy or the idea that “literature inspires empathy,” Cole channels many a jaded journalist. And yet, he writes, it is true that sometimes much worse than taking a photo is not taking it, or not being allowed to take it, and horror must sometimes be looked at. Alongside Caravaggio’s masterful depictions of gruesome scenes, Cole scrutinizes a video captured in a Libyan slave market. As he writes in a fragmentary essay on Syria (its atrocities and its art), “I need to understand what I am sad about, not in hopes of obliterating the sadness, but in hopes of lessening it.” Perhaps the point is that we ought to look at documentary evidence the way we look at paintings—for meaning, not for information. “When you’re looking at a field,” he notes, “someone can always walk across that field. A painting, on the other hand, is settled. It is there to be looked at. It stills the frenzy of the human heart.”

Photographs nonetheless offer Cole a chance to move lightly across his forms and themes, as in an “incantation” about the photographer Marie Cosindas, whose cluttered, warmly colored compositions, Cole says, are “like watching a single sentence unfurl over several pages, driven along by an invisible, inner consistency.” The entire six-page essay is one such sentence. “Shattered Glass” begins with the image of the holes made in the windows of the Las Vegas Mandalay Bay resort by a mass shooter in 2017 and meanders through the history of glass in the photographic technique—today, “the mobile phone is a kind of window, and it is always on the verge of breaking.”

This collection of Cole’s feels rawer and more personal than those that have come before—Blind Spot and Known and Strange Things—layering as it does his art essays with homages to lost friends and analysis of his own 2012 novel, Open City. There are moments when the self-citation begins to feel self-indulgent or when the highbrow tips into the merely pretentious (as with his studious avoidance of naming “the tweeting president”). “Conversations between characters are all well and good; countesses must, I suppose, sweep into rooms, as they do in certain novels. But the secret reason I read,” Cole confesses, “the only reason I read, is precisely for those moments in which the story being told is deeply alert to the world.” I admit I share his preference for novels that feature unsettling encounters with landscape or art over countesses, but I am still relieved when he shows a little sense of humor. (Looking at old paintings, he writes, “can sometimes feel like a diverting, or irritating, stroll among White people’s ancestors.”)

Cole attempts to be of his time, and the particular political mood of the early Trump years provides a backdrop to these essays—they were written amid that perpetual foreboding, the clenched teeth and depression, the outrage so often articulated that the bottom fell out of the word. But it is art that abstracts itself a few steps from the present that most inspires him: Watching, for instance, newly declassified footage from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s YouTube channel of nuclear weapons tests in light of Trump’s nuclear brinkmanship leads him to consider photographic responses to the disaster at Fukushima, images “simultaneously primordial and futuristic,” relaying the “curious twinship of mourning and premonition.” The work of the photographer Lorna Simpson and the painter Kerry James Marshall offer Cole similar distance and solace in his confrontations with the contemporary burdens of Blackness.

The newest essays in the book, originally given as a series of lectures in 2019, treat the topic of the senses. Brief but expansive riffs on synesthesia and belonging, and on epiphany and experiences that stop a little short of it, reflect the flaneur’s ideal that noticing is a form of affection and an ethic: “To list is, somehow, to love.” Citing examples from W.G. Sebald, Orhan Pamuk, and Toni Morrison, he engages in this list-making himself, excerpting Open City’s descriptions of New York at length and cataloging his meandering in Beirut, Naples, Oslo, and other cities he comes to know. This ethic connects, in turn, to his heavier subjects, to writing as “testimony” and a “commitment shored up by history” and the difficult work of bearing witness. The feeling of sadness that obviously motivated these essays, the feeling of being weighed down by all one is called to see—the phrase is bearing witness, after all—is made lighter by the example of other artists, the potential for joy in sensing all the world is.