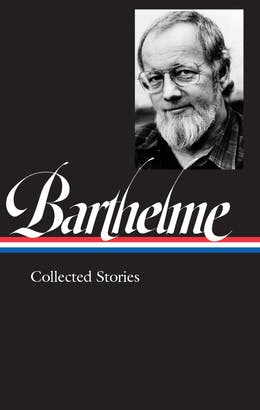

Decades after his premature death—in 1989 at the age of 58—Donald Barthelme might be the one indisputably minor American short story writer of the last century who remains a pleasure to read and reread. He focused primarily on surreal, unpredictable short stories that were often good but rarely great. He experimented with form restlessly and surprisingly from one story to another but rarely created anything that hadn’t been seen before in the works of those writers he admired—Samuel Beckett, Arthur Rimbaud, Gertrude Stein, Alain Robbe-Grillet and S.J. Perelman. He could amuse the heck out of readers but rarely made them laugh out loud. And he composed each story as if it were an idiosyncratic fling designed to please nobody but himself.

At a time when American fiction was growing almost too ambitiously wild and unpredictable—with big, staggeringly imagined works coming from Thomas Pynchon, John Barth, William Gass, and William Gaddis—Barthelme remained true to his smaller, more easily graspable absurdities. He was, in fact, about as wild and wacky as the sometimes unbearably sensible New Yorker ever got. Which is to say—not that wild and wacky at all.

As his biographer and former student Tracey Daugherty recalled, when Barthelme taught creative writing at the University of Houston in the 1980s, he gave his students the following assignment:

Find a copy of John Ashbery’s “Three Poems,” read it, buy a bottle of wine, go home, sit in front of the typewriter, drink the wine, don’t sleep, and produce, by dawn, twelve pages of Ashbery imitation.

The intention was clear—to force his students to stop overthinking and over-managing their work and just let the words flow. These were all hallmarks of the Barthelme “method”—one that served him well enough to produce more than a hundred short stories, five novels, several failed marriages, and countless failed relationships, and a career-long ability to charm readers even when those readers had no idea what he was doing.

Of course, people who develop well-organized methods of “loosening up” are rarely very “loose” to begin with. The premier “de-loosener” in Barthelme’s life was probably his father, a Houston-based architect inspired by Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe. As Donald’s brothers Frederick and Steven described it in their grueling memoir, Doubling Down, the family home that their father designed was a wild agglomeration of wood and copper siding filled with “elegant Saarinen chairs, the bent birch of Aalto dining tables and chairs, almost every piece of furniture or fabric that Charles and Ray Eames ever designed.” It was the sort of house that would make a young man like Donald into something of a bricoleur, while at the same time teaching him to hate bricoleurs. Another Barthelme brother, Peter, described their father as a “verbal bully,” and it seems as if his imposing presence and intelligence both inspired his many talented children and cast a shadow that none of them ever escaped.

A girlfriend reported attending one of the father’s frequent slide shows in which he deliberately lingered over a photo of Donald’s first wife, just to see how it might affect her. He was continually berating Donald for his avant-garde tastes in art and literature, which probably only made Donald more determined to maintain them. The Barthelme house was such a discordant site in the Houston suburbs that people often stopped their cars and got out to stare, and at one point, the Barthelme family en masse came outside to perform high kicks in a chorus line until the annoying looky-loos drove off home to their boring modular lives. It’s hard not to see the entire Barthelme oeuvre—now canonized in a Library of America edition—as a similar sort of performative jeering at the conformist 1950s in which Barthelme was raised.

Barthelme might have had a less successful career if not for a few decent bursts of luck along the way. His youthful occupation as a museum curator developed in him a fondness for discordantly arranged items and subjects, and as an influential, prescient editor of Forum at the University of Houston, he became an early proponent of the likes of Gass, Norman Mailer, and Walker Percy, all of whom eventually (and not coincidentally) became early proponents of Barthelme. Through these developing connections, he found an important literary agent in New York, and in 1963 he was taken on board by the most powerful fiction editor of his time, Roger Angell at The New Yorker.

Angell had never displayed much interest in avant garde fiction, but Barthelme seemed to fit into The New Yorker’s fictional timeline quite neatly—providing a segue from the end of S.J. Perelman’s long career (he was one of Barthelme’s early fictional influences) to Woody Allen. Manhattan was the perfect subject for Barthelme’s comic method, and he certainly produced most of his best short fiction while living there in the 1960s and 1970s. The city-jumble of always-shifting relationships between people, their jobs, and their locations on the city map provided the perfect ambience for stories in which weird things just generally happened as part of the landscape. And the medley of feelings that strike an individual simply by walking up and down the same busy and always changing streets—sadness, joy, surprise, wonder, boredom, fear, anomie, angst—is just the emotional soundtrack that a typical Barthelme story requires.

Barthelme’s was a restless, hungry and, to a large extent, unformed intelligence, and almost every one of his stories encapsulates his odd narrative charm in all its loose and shaggy glory. A lifelong “fan of” (rather than, say, “adherent to”) the existentialism of Sartre and Kierkegaard, he sympathized with their notions of the human personality as a vast, always-yearning shopping bag of emptiness. In his story “Daumier,” the central character designs surrogates who can go out in the world and (unlike their progenitor) achieve satiation. The “authentic self,” the narrator argues,

is a great dirty villain.… It is insatiable. It is always, always hankering. It is what you might call rapacious to a fault. The great flaming mouth to the thing is never in this world going to be stuffed full.

For Barthelme, the notion that individuals are continually “hankering” after more stuff with which to make themselves feel whole is more than a philosophical concept—it was a way of producing stories that often resemble hungry collages of various wild stuff the author has seen, imagined, imitated, and heard—which is probably why the typical Barthelme paragraph is stuffed with numerous unrelated facts, fantasies, quotations, and the names of real people who aren’t actually the real people they might have actually been. (Such as, for example, Daumier, and the surrogates he releases into the world.)

Some of his earliest stories in Come Back, Dr. Caligari (1964) are so densely fragmented with allusions to artists, philosophers, and pop icons, and so thin on anything resembling a story or a point of view, that they can be hard to follow. The oddly sculpted sentences are stitched together like tessellated fragments of absurdist comedy, like swathes of Bretonian automatic writing that have been systematically rewritten to elicit pleasurable, and pleasurably broken, prose rhythms.

Under Angell’s editorship, Barthelme’s stories grew imaginatively leaner and less chaotic, and the wild dense surrealist flights of his early stories were threaded along thin semblances of plot that usually somehow worked. “The aim of literature,” a character pronounces (in one of the earliest stories, “Florence Green Is 81”) “is the creation of a strange object covered with fur that breaks your heart.” For Barthelme, they were words to live by both inside and outside the realm of his fiction, for he seemed like a man whose heart was broken many times.

Barthelme always seemed to be fleeing one formal restriction for another—marriages, jobs, homes—and the same dynamic played out in his fiction, which began blossoming in the mid-1960s during his second divorce. He roved constantly and restlessly from one idiosyncratic story structure to another. He told stories in the form of text and marginal commentary (“To London and Rome”), as a sequence of bubble-like bursts of experience (“Bone Bubbles”), as a tourist guide to a country that sounds like one we recognize but is actually another country entirely (“Paraguay”), as a six-page single sentence that never finds its ending, and as a lengthy catechism that begins:

In the evenings, usually, the catechist approaches. “Where have you been?” he asks.

“In the park,” I say.

“Was she there?” he asks.

“No,” I say.

Most of his stories read like collages of facts, nonfacts, imaginary blips and bleeps, and quotations from famous figures that might or might not be entirely accurate (Schlegel, Daumier, Goethe, Kierkegaard all commonly appear, or are quoted); others include actual collages that operate more as discordant juxtapositions than as commentaries—as in “At the Tolstoy Museum,” which features some geometric lines and mismatched pillars surrounding a huge bust of the Russian novelist over the caption: “Museum plaza with monumental head (Closed Mondays).” Or “The Explanation,” in which “Q.” and “A.” debate the qualities and uses of a “machine” that is illustrated by a recurring large black box that takes up a third of the page and seems to signify nothing. (Another story is titled “Nothing: A Preliminary Account.”)

Then, of course, there was “The Balloon,” one of Barthelme’s most reprinted and celebrated stories, which assembles roughly five pages of public commentary on the appearance of a non-specifically described balloon that appears above Manhattan’s 14th Street (“the exact location of which I cannot reveal”) and “expanded northward.” And while the balloon elicits much “public warmth” from “ordinary citizens,” the critical reaction bristles with complications:

::::::: “abnormal vigor”

“warm, soft, lazy passages”

“Has unity been sacrificed for sprawling quality?”

“Quelle catastrophe!”

“munching”

Postmodern lists of unrelated items and categories abound in a typical Barthelme story. The meaninglessness of personal life extends everywhere—into marriages, families, careers, cities, politics, and even the sky—across which Barthelme’s balloon-image of everythingness soars free from everything except human interpretation. His characters go looking to meet women at Manhattan loft parties where they encounter King Kong being groomed by his girlfriend, Cynthia Garmonsway. (“Cynthia formerly believed in the ‘enormous diversity of things’; now she believes in Kong.”)

And they often find themselves losing ground in systems of relationships that seem like surreal versions of musical chairs—every time the music stops, there are either fewer chairs or fewer players. In “City Life,” he charts the multitudinous relationships that come spinning out of Elsa and Ramona’s arrival to “the complicated city,” which involves their potential partners Jacques and Charles, a fireman named Vercingetorix, and a blues singer named Moonbelly, who achieves some commercial success with his hit record, “Cities Are Centers of Copulation.” When Ramona gives birth to a boy, she avoids the problem of assigning paternity by claiming it’s just “an ordinary virgin birth.” And yet however much Ramona tries to “soft-pedal” the idea, people “persisted in getting excited about it.” In Barthelme’s stories, love isn’t an act between two people; it’s a sort of sociopolitical riot.

But even when the stories bear some semblance to what readers might think an ordinary story looks like (wherever the hell that is), Barthelme never stops banging around and smashing and rearranging his words into sentences and his sentences into paragraphs until there’s hardly a predictable phrase or syntactical arrangement in sight, as if he was roving through traditional grammar textbooks with a wooden mallet and sticking the broken shards in attractive little configurations with anonymous white paste from a child’s school art project. Every passage is a form of play—the play of the author with the reader, the play of the reader with each weird little contraption of story, and the inevitable play of readers with one another. (“What the hell did the balloon represent?” “Maybe it didn’t represent anything!” “Maybe it did!”)

As Barthelme iterated in various interviews and essays at various times: “Writing should be playing, you know.” And it was his blithe addition of “you know” that made it clear he didn’t consider there was any other way to write. His stories are like magpie nests of brightly gleaming oddities and mismatched subjects. And while the stories were always surreal, they dealt with mundane realities: the inhospitality of men to women (and vice versa); the boring and inexplicable nature of most jobs and professions; and the unpredictability of everyday life, which leads to a sense of almost exhausted irony on the part of Barthelme’s protagonists.

At its worst, Barthelme’s quirkiness can wear you down, and reading a massive collection of Barthelme in one dense LOA volume like this might, at times, feel like a terrible responsibility. Each story features so many elisions, random juxtapositions, and broken categories of meaning that even the swift clear sense of narrative closure that usually arrives in the final paragraph can’t prevent a reader from thinking: OK, that was amusing. So what?

Barthelme’s may be a meaningless world, but it is not an unbelievable one, especially coming out of the consumer-mad 1960s and ’70s, when everybody was filling their homes with junk they didn’t need. And while the political nature of Barthelme’s fiction doesn’t grow much more elaborate than ironic commentary on urban consumer culture, it’s hard to read any of his stories without laughing, or smiling, or maybe doing a little of both. Friends recalled that when he wrote, he typed away happily, laughing out loud as he wrote; and it is one of the pleasures of reading him that our pleasures feel like they’re being shared with the now dead author.

In his later years, Barthelme’s innovative fictions grew slightly less exotic and surprising. He began producing more personal and reflective stories, such as the title story of “Overnight to Many Distant Cities,” in which the collage of wild narrative fragments includes items culled from his own life—such as a teenage misadventure in Mexico that Barthelme enjoyed with one of his brothers. And many of his late stories focus on the private lives of men and women who were—like Barthelme and his various partners—lively, sad, lost, gentle, angry, and always searching for the next relationship or story. Like the narrative presence that reveals itself at the conclusion of “The Dolt,” Barthelme lived each day, and wrote each story, with the knowledge that: “Endings are elusive, middles are nowhere to be found, but worst of all is to begin, to begin, to begin.” Barthelme’s humor is very unlike that of Beckett, who saw the shadow of endings looming blackly over every human striving. For Barthelme, the world was almost always ironically starting over again into the next weird and remarkable story. Until, of course, the stories stopped with Barthelme’s premature death by throat cancer—which almost certainly resulted from a lifetime of excessive smoking and drinking.

By the time Barthelme died, the meta-fictional landscape had pretty much already subsided—and with the possible exception of Pynchon—whose fabulations were growing increasingly concerned with the real world of Reaganomics (Vineland) and 9/11 (Bleeding Edge)—most of the writers who attended Barthelme’s Postmodern Dinners in New York were fading from center stage in Manhattan’s always-fickle literary scene. But while the likes of Barthelme, Gass, Robert Coover, and Walter Abish were no longer celebrated as much as the new generation of so-called “minimalists,” it’s hard not to see Barthelme’s influence in the work of those who came after him: Raymond Carver, Tobias Wolff, Ann Beattie, Richard Ford, and even Donald’s younger brother Frederick. These so-called more “realistic” writers all seemed Barthelmian in their own quiet ways, producing short and loosely plotted stories about lost people in broken relationships, always moving homes and jobs, and never quite happy wherever it is they happen to be. They told their stories, like Barthelme, as sequences of short, eccentric, perfectly formed little scenes. And just like Barthelme, they broke our hearts, over and over again—whether wild or mundane, weirdly unbelievable or all too believable—with reflections of our common, ineffable, and totally surreal human life.