In

March 2007, The Spectator, the London weekly magazine, published a truly

remarkable column. “Prepare

yourself for a veritable carpet-bombing of name-dropping,” its author said, and

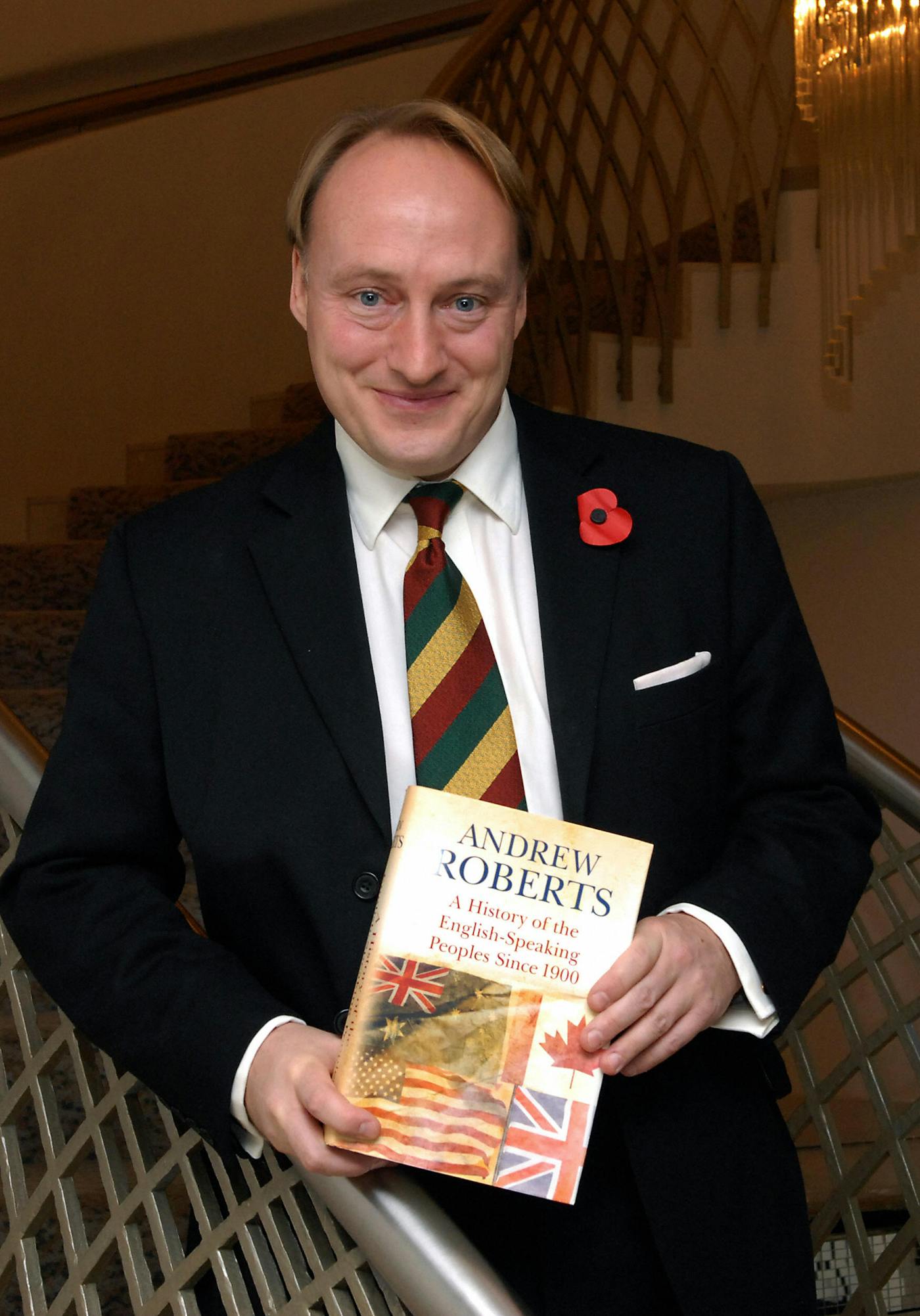

he wasn’t kidding. Andrew Roberts had

published a new book, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples Since 1900,

a continuation of, and homage to, Sir Winston Churchill’s History of the English-Speaking

Peoples. Now Roberts was following in his hero’s footsteps to America for an author

tour like no other.

In New York, which he was pleased to say “radiates reactionary chic,” Roberts was greeted by Tom Wolfe, Norman Podhoretz, and Jayne Wrightsman, before “Harry Evans and Tina Brown gave a dinner for 50.… The following night Henry and Nancy Kissinger gave a dinner party” where he met George F. Will, Peggy Noonan, and Rupert Murdoch (“charming, witty, good-natured, and even slightly retiring”). But that was nothing as compared with the welcome that awaited him in Washington. First he bumped into John Bolton, “who said he was enjoying the book,” before Irwin Stelzer threw a big party, “and his friends Irving and Bea Kristol, Charles Krauthammer, Richard Perle, and Charles Murray stayed for dinner afterwards.”

A picture was already forming of this Englishman and his American admirers even before the next day at the White House, where “we were asked if we’d like to spend some time before lunch in the Oval Office with ‘the reviewer-in-chief.’” Ushered into the presence, “I had 40 minutes alone with the Leader of the Free World, talking about the war on terror.” President George W. Bush “was full of resilience and fortitude—as I’d taken for granted he would be—but he was also thoughtful, charming and widely read.” Then to lunch, where he met Karl Rove and Dick Cheney. As it happened, Cheney had just returned from “Bagram air base in Pakistan” (Roberts meant Afghanistan, but then these pesky stans are so confusing), where he was seen boarding USAF Strom Thurmond with Roberts’s book under his arm. And yes, the aircraft that was bringing democracy and equality to the benighted Pashtuns really was called that, after the South Carolina governor and then senator who for so long insisted that “all the laws of Washington and all the bayonets of the Army cannot force the Negro into our homes, into our schools, our churches.”

Since then, Roberts has written more books, including a biography of Churchill three years ago. Here is where I come in, and where some disclosure is called for. My own new book, Churchill’s Shadow, has just been published in London and shortly comes out in New York. Both books divided opinion. In my case, some reviewers liked the book, but Roberts didn’t—he really didn’t, as he made clear in a two-page diatribe in the Spectator, of which more later.

But first of all, who was this truly unusual author with such a stellar array of friends and fans in Washington? Now 58, Andrew Roberts was educated at Cambridge and published his first book in 1991, a biography of Lord Halifax, the foreign secretary who might have succeeded Neville Chamberlain as prime minister in the crisis of May 1940 but made way for Winston Churchill. And a very good book it was, justifiably establishing Roberts’s name, before he followed with another fascinating book, in 1994, a collection of essays called Eminent Churchillians. One essay was a ferocious assault on Lord Mountbatten’s reputation, another described the hostility so many Conservatives felt toward Churchill until or even after he became prime minister, and one more, maybe the most revealing, was on “Churchill, Race and the ‘Magpie Society,’” looking hard at his racial attitudes, or simply his racism.

Over the next quarter-century, Roberts published numerous books, some better than others, ranging from a full-dress biography of Lord Salisbury, Queen Victoria’s last prime minister, to others that were frankly potboilers. But he also found another career, as a polemical journalist or provocateur, describing himself as “extremely right-wing.” Once again, he wasn’t kidding. A quarter-century ago, when others favored Western intervention in the bloody Balkan conflicts, only Roberts advocated the use of tactical nuclear weapons against Serbia. Fast-forward to early this year, when most people thought that the horrible riots at the Capitol on January 6 were the work of right-wing fanatics, but only Roberts insisted that the blame for the violence lay squarely with Hollywood liberals. From then to now, he has never been afraid of voicing views for which extreme is the word, though not the only one.

It almost goes without saying that he has long been passionately hostile to the European Union. In 1995, he published a quaint dystopian thriller, or something, called The Aachen Memorandum. Set 20 years later, in 2015, it described an England absorbed into the United States of Europe after a referendum rigged by a pro-European elite, while Iain Duncan-Smith, Niall Ferguson, and Michael Gove are freedom fighters in an underground Anti-Federalist Movement, and John Redwood leads a “Free British” group from Oslo (the names are all Europhobic politicians and pundits). I remember the editor of a Conservative national newspaper remarking to me at the time that the book was one more example of how “Europe” drove right-wingers stark mad.

His

politics intruded even into Roberts’s weightier books. The 1999 biography

of Salisbury was dedicated to Margaret Thatcher, linking her with Salisbury, by

way of a phrase of his, as an “illiberal Tory.” For Roberts, this was the highest

term of praise for both of them, although they really had far less in common

than that suggests. Salisbury was a brilliant diplomat and a great foreign

secretary, but in domestic politics a mere embodiment of reaction, or inaction.

By following his own laconically expressed principle, “Whatever

happens will be for the worse, and therefore it is in our interest that as

little should happen as possible,” Salisbury ensured that both Irish Home Rule

and social reform were delayed by a generation. “Mrs. T” was in many ways the opposite, “a woman who through character and

conviction changed the country,” and you’d need more than one guess for who

wrote that unlikely if accurate tribute, which is to say Perry Anderson of the New Left Review.

Nor were Salisbury and Thatcher Roberts’s only heroes. Within a matter of years of Eminent Churchillians, he had become a preeminent Churchillian himself. In 2000, he gave a lecture on “Churchill and His Critics” at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. This was where Churchill gave his famous Iron Curtain speech in March 1946, and Westminster College has since become the most wondrous of all Churchillian shrines, with iconography ranging from a Christopher Wren church transported bodily from the City of London to a large statue of Churchill to a part of that Iron Curtain, in the form of a piece of the Berlin Wall.

In his lecture, Roberts took on Churchill’s critics with his usual intransigence. Listing all the great controversies in Churchill’s life—Gallipoli in 1915, intervention in Russia in 1919, rejoining the gold standard in 1925, the general strike the following year, his campaign against Indian nationalism in the 1930s, the fire-bombing of Germany in 1942–45, and much more besides—Roberts concluded, “I personally believe he made the right choice in almost every single one of those cases, displaying a far better track record of good judgment than any of his contemporaries.” That was a truly remarkable verdict, and more than Churchill himself thought, regretting, in particular, the gold standard decision and uneasy about the killing of half a million German civilians by bombing.

Besides, Roberts defiantly claimed that “the English-speaking peoples seem to have a settled view of Churchill’s glory which no amount of historical debate will now alter.” But do they, or should they? And who are these “English-speaking peoples,” anyway? We learned more when Roberts published that book that wowed the Bush administration, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples since 1900. The phrase “English-speaking peoples” had been current since the nineteenth century, but Churchill took it up at an interesting time. During the 1920s, like many politically conscious Englishmen, he was bitterly resentful of the U.S. The Americans had entered the Great War later than he thought they should have done and then suffered few casualties by European standards, before the postwar years when they had implacably insisted on the repayment of war debts from England.

In 1928, Churchill was growing restless as chancellor of the exchequer (a position for which he was exceptionally ill equipped) and thought of moving to be foreign secretary, when his wife, Clementine, reminded him of the difficulty: “Your known hostility to America might stand in the way.” But the following year, a luxurious and lucrative American tour quite changed his mind, and the seeds were planted of what he was originally, and significantly, going to call a history of “the English-speaking races.”

By the time Roberts wrote his sequel, he was not only self-appointed keeper of the flame but more Churchillian than Churchill. At the grim conclusion of the Boer War in 1901–02, Boer civilians were interned in concentration camps—yes, we called them that—where appalling numbers of women and children died. The horror was heroically exposed by Emily Hobhouse, an Englishwoman; bravely denounced by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the leader of the Liberal Party; and abhorred by Churchill: “I have hated these latter stages with their barbarous features.” But not by Roberts, who wrote that the blame for the concentration camp deaths lay with their inmates themselves, and their insanitary habits.

In similar manner, the Amritsar massacre in the Punjab in 1919, when at least 379 Indians were killed by troops of the Raj, was denounced by Churchill in Parliament: “Frightfulness is not a remedy known to the British pharmacopoeia.” But not by Roberts, who defended the massacre for having restored order: “It was not necessary for another shot to be fired throughout the entire region.” No wonder that The Economist called this book “a giant political pamphlet larded with its author’s prejudices,” while Jacob Weisberg wrote, in Slate, a piece entitled “Bush’s Favorite Historian: The strange views of Andrew Roberts.” Apart from noting that the book was littered with obvious mistakes, Weisberg was startled by Roberts’s fanatical tone: “The fire-bombing of Dresden was ‘justified,’ the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki positive in various ways. The abuses at Abu Ghraib, Roberts writes, were of course overstated and resulted from ‘the fact that some of the military policemen involved were clearly little better than Appalachian mountain-cretins.’” And he concluded that “with this book, Andrew Roberts takes his place as the fawning court historian of the Bush administration.”

What even such critics failed to notice was that the thesis of that book is simply false. It purports to relate “the four world-historical struggles in which the English-speaking peoples have been engaged: the wars against German nationalism, Axis fascism, Soviet communism, and fundamentalist terrorism.” They may have been “engaged” in those struggles, but they didn’t win them. Kaiser Wilhelm II’s imperial Germany was defeated by the blood-sacrifice of the French army, and “Axis fascism” was defeated by the blood-sacrifice of the Red Army, with the English-speaking peoples playing a decidedly lesser part. Nor did those English-speaking peoples “fight Communism” together except once in Korea, but that was the first—and so far the last—war fought under the auspices of the United Nations, with French, Turkish, and Indian troops, as well. British soldiers conspicuously did not fight in Vietnam, although President Johnson very much wanted at least a token British force.

But of course the whole point of that decidedly teleological book was the last struggle, against “fundamentalist terrorism.” As Weisberg said, Roberts was “present-minded in the extreme, returning at every stage of his narrative to justifications for Bush’s actions in Iraq. The neoconservatives who want to spread democracy in the Middle East are the heirs to compassionate Victorians who sought to civilize India, China, and Africa.” In one of his weirder passages, Roberts wrote that “just as in science-fiction people are able to live on through cryogenic freezing after their bodies die, so British post-imperial greatness has been preserved and fostered through its incorporation into the American world-historical project.”

Two years after his visit to the White House, and quite undaunted by events, Roberts was still insisting that “history will show that George W. Bush was right: Iraq has been a victory for the US-led coalition, a fact that the Bush-haters will have to deal with when perspective finally—perhaps years from now—lends objectivity to this fine man’s record.” He continued to write books on sundry subjects, including Napoleon, whom he greatly admires, and then his Churchill biography. One reviewer thought his book the best one-volume life of Churchill, and another called it “a thousand pages of literary purgatory.” A more balanced view came from Gerard DeGroot, a professor at St. Andrew’s University, writing in the London Times. He didn’t dismiss the book but found it “more reportage than reflection,” and a work that “harks back to those relentlessly adulatory hagiographies produced immediately after the war.” Roberts’s basic technique was simple: Whenever Churchill did something admirable or said something noble, he was extolled; whenever he did something deplorable or said something ignoble, he was extenuated, usually by way of claiming that he was simply a man of his age. Again and again, Churchill will say something shocking, and we will be told that everyone else said the same. If he is right and virtuous, he is uniquely so, if he is wrong and repugnant, well, so was everyone else.

Since that book was published, Roberts has found yet another hero: “This is your Churchill moment, Boris,” said one of his recent headlines, or again, “MPs love to complain about Boris. But his hero also endured a barrage of unhelpful criticism,” or yet again, “How Boris is taking lessons from his hero Churchill.” To which I will only say that if Mike Huckabee hadn’t watched the movie Darkest Hour and then tweeted “in @realDonaldTrump we have a Churchill,” then there could be no more entirely ludicrous comparison than between Winston Churchill and Boris Johnson.

Authors should keep quiet about reviews, or at least confine their plaints to friends, as Evelyn Waugh did in a letter to Sir Maurice Bowra, “I’m glad you liked my book. The reviewers don’t, fuck them.” In fact, the London reviews of my book have been friendly enough, except for that howl of rage by Andrew Roberts. Not only is my book a “character assassination too far,” he says, full of mistakes, some of which traduce Churchill, it is “relentlessly sneering” and written in a “tone of perpetual snideness.” Others must judge, but it’s hard to reconcile those words with Dominic Sandbrook’s verdict in The Sunday Times that “this book is never mean-spirited, and never degenerates into a demolition job.”

What seems to have bugged Roberts is the sheer lèse-majesté in challenging his own holy writ; his view that Churchill “made the right choice in almost every single one of those cases” discussed above, or that there should be “a settled view of Churchill’s glory which no amount of historical debate will now alter,” views I certainly dispute. His title, Churchill: Walking With Destiny, echoes Churchill’s own exalted words: that upon his appointment as prime minister in May 1940, “I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.” Roberts follows this to the extent of dividing his book into two parts, “The Preparation” until May 1940 and then “The Trial.”

An alternative view comes from a great historian. My revered friend Sir Michael Howard died almost two years ago, the day after his ninety-seventh birthday. He wrote a still unsurpassed history of the Franco-Prussian War and many other books, was Regius professor of modern history at Oxford and then a professor at Yale, as well as one of the 24 British holders of the Order of Merit, and much else besides. Besides, he was a scornful critic of the Bush administration and its unneeded and unwinnable wars, calling the invasion of Iraq “a bad idea whose time has come.” But then, unlike the men who thought up that bad idea, he knew something of the reality of war. At Salerno, in 1943, Lieutenant M.E. Howard of the Coldstream Guards won the Military Cross leading his platoon in a night action against German lines, a contrast indeed to the saber-rattling draft-dodgers and flag-waving chicken hawks of the Bush administration.

A lifetime later, that old soldier wrote, “The problem, for the historian, is not, as so many Americans believe”—and have been encouraged to believe by hero-worshipping biographers—“why Churchill’s advice was ignored for so long, but how it was that a man with so unpromising a background and so disastrous a track record could emerge in 1940 as the savior of his country.” That’s a problem that I have at least tried to address, quite unlike Roberts, for whom, in his belief that Churchill had “a far better track record of good judgment than any of his contemporaries,” the problem doesn’t exist.

Indeed, so angrily determined is he to defend Churchill at all times and in all ways that he makes claims that are demonstrably false. My “insinuation that Churchill had fascist leanings in the 1920s is not supported by anything better than quotes from his avowed political enemies,” Roberts shouts, thereby drawing a magisterial rebuke from Lord Lexden, a former Conservative Party official and a learned political historian: “How much more effective Andrew Roberts would be if he did not feel impelled to defend Churchill against almost every hint of criticism. He denies that Churchill had ‘fascist leanings in the 1920s,’” and yet, “visiting fascist Italy in 1926, he declared that ‘your movement has rendered a service to the whole world’; as late as 1937 he spoke of ‘the enduring position in world history which Mussolini will hold.’”

But still on Roberts goes, often with preposterous defenses of his hero, in the pages of the right-wing Daily Telegraph, and in a new podcast called “History Defended,” culminating in what must be the most sublime sentence of all: “Black lives mattered to Winston Churchill, which is why he fought to defend the empire on the northwest frontier of India.” He really did say that. Well now, in 1897, Churchill “fought to defend the empire” in a punishment mission against the Pashtuns of Afghanistan. As he wrote to a friend, “After today we begin to burn villages. Every one. And all who resist will be killed without quarter … there is no doubt we are a very cruel people.”

The following year he fought in Sudan against the Mahdi, the bin Laden of his age, and the people the British of the time called the dervishes, his ardent Muslim followers. “I have a keen aboriginal desire to kill several of these odious dervishes,” Churchill wrote to his mother, and so he did at the battle of Omdurman, killing several himself among the 10,000 who were wiped out mostly by machine-gun fire. Much later he called the Hindus “a foul race,” and during the terrible Bengal famine of 1943, when colleagues were shocked by his indifference to the horror compared with his response to reports of famine in Greece, he said, “The starvation of anyway underfed Bengalis matters less than that of sturdy Greeks.” And in his very last Cabinet meeting as prime minster before he retired in 1955, he said the Conservatives should fight the forthcoming election on the slogan “Keep England white.” Yes, Black lives mattered to Churchill.

My own view would be that, although racial attitudes in general were obviously different 80 years ago from ours today, even then, “Churchill was more profoundly racist than most.” Who could have written that? Why, it was Andrew Roberts in his “Churchill, Race and the ‘Magpie Society.’” In that essay in 1994, Roberts quoted Desmond Morton, one of Churchill’s wartime aides, who recalled his private language: “Negroes were ‘n----s’ or ‘blackamoors’, Arabs were ‘worthless.’” And the Chinese and Indians were described in ways one prefers not to print these days. As Roberts wrote then, Churchill “was a convinced white—not to say Anglo-Saxon—supremacist and thought in terms of race to a degree that was remarkable even by the standards of his own time … in a way which even as early as the 1920s shocked some Cabinet colleagues.” All of which is to say that Churchill’s views and vocabulary were very much not “perfectly orthodox thinking at the time.” At which point one begins to wonder, does Andrew Roberts actually read his own books?

He is also indignant at my writing about “what he calls ‘the Churchill cult,’” which implies that I have made up this phrase and concept, when the existence of a Churchill cult in England, but even more in America, has been discussed for decades past. The very first issue of the satirical magazine Private Eye in 1961 bore the spoof headline “Churchill cult next for party axe?” (meaning the Tory Party), before Christopher Hitchens included an essay called “The Churchill Cult” in his 1990 book Blood, Class, and Nostalgia.

And this spluttering vexation is comical coming from a man who is veritably the L. Ron Hubbard of the Churchill cult. Roberts described another book tour, for his Churchill biography: “I’ve just returned from a ten-week, 18-state, 27-city, 87-speech book tour there, and can report that the enthusiasm for all things Churchillian in the USA is stronger now than at any time since his death. Merely bringing out a new biography of him secured me interviews on all the major TV morning news shows, invitations to speak at three presidential libraries, and a place on The New York Times bestseller list for nine weeks. There are active Churchill appreciation societies in 14 states and more being set up.” He ended this tour in Texas, where he admired “George W. Bush’s excellent portrait that hangs in the Dallas Country Club” before “dinner à trois with the former president and Laura Bush.” And there is no Churchill cult?

But maybe the real key to Roberts’s anger becomes clear when he accuses me of deriding “anyone who has had the temerity to admire Churchill” or “who has sought instruction or inspiration from his life and career.” It’s hard to see what temerity—“excessive confidence or boldness”—is really required to admire him, since people do it the whole time. And yet whom could he have in mind? Well, of course, he means people such as that “fine man” George W. Bush, who loved to stand in front of the bust of Churchill in the Oval Office while quoting him, as well as Roberts’s other friends in that fine man’s administration, Cheney and Bolton and the likewise Churchill-spouting Donald Rumsfeld.

One of my themes, while describing Churchill’s remarkable afterlife, is that his name has been endlessly invoked, along with the names of “Munich” and “appeasement,” which he turned into curses. And yet on every single occasion when that has happened, it has unfailingly led to disaster, with Korea, Suez, and Vietnam among the earlier cases. But never has Churchill ’s name played such a part as in the wars in Afghanistan, where he fought as a young man, and Iraq, a country he almost invented. One might say that there was no shortage of excessive confidence or boldness 20 years ago among those in Washington who sought instruction or inspiration from Churchill. Whether that inspiration led to glorious victory, judge for yourself.

One last word. My book is not intended to be “relentlessly anti-American,” as Roberts calls it, and I don’t believe it will seem so except to a “fawning court historian of the Bush administration” or to anyone else who thinks that Bush was a fine man and that “Iraq has been a victory for the U.S.-led coalition.” Nor is it intended to be merely an assault on Churchill. “Will biographers of Churchill ever break the habit of either lauding or denigrating him unduly?” Lord Lexden writes in his rebuke to Roberts. “They shirk the historian’s central task, which is to weigh up this extraordinary man’s successes and failures calmly and dispassionately.”

By contrast with some others, I’ve at least attempted to do just that. And I honestly believe that Churchill has suffered less from his critics than from adoring hero-worshippers and cultic appropriation. Andrew Roberts is only one, though a notable one, of those who have not only extolled Churchill but used him as an icon, in the full sense, like the holy images once held up before the Czar’s armies as they marched to battle, and often to death and defeat. Churchill’s shroud was waved to justify the invasion of Iraq, and then Brexit. In these and other cases, the shroud-wavers suppose that Churchill was uniquely wise and far-seeing, when he was quite obviously and gravely wrong about many things for much of his life.

He was right in 1940, gloriously right, when his magnificent defiance of Hitler was a rare personal triumph that changed the course of history. And I say so not least because the Churchill of the Finest Hour deserves to be rescued from hagiographers, court historians, and a certain “extremely right-wing” polemicist.