In June, Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds signed a bill that prohibits “race scapegoating” and “race stereotyping” in K-12 education, as well as teaching “specific concepts” such as “the United States of America and the state of Iowa are fundamentally or systemically racist.” The law, which targets critical race theory without naming it, defines race scapegoating as “assigning fault, blame, or bias” to a race or sex “because of their race and sex,” or claiming members of that race or sex are “inherently racist”—consciously or unconsciously. The bill is in the spirit of a dead measure from Iowa that sought to cut funding to schools that teach The New York Times’ 1619 Project, claiming it attempts to “deny or obfuscate the fundamental principles upon which the United States was founded.”

Iowa is one of 26 states that have introduced bills to restrict language that indicts white Americans in perpetrating slavery and anti-Black racism. Many of the bills sample from one another, echoing the same refrain: The 1619 Project and critical race theory are “racially divisive,” indoctrinating students into anti-American ideology. Eleven states have enacted bans on “critical race theory,” but with the exception of Idaho’s, “critical race theory” is not mentioned in the legislation. States with measures to defund schools that teach the 1619 Project are more explicit in their repudiation. A Texas bill says that “teachers may not require an understanding of the 1619 project,” and Arkansas called the 1619 Project a “racially divisive and revisionist account of history” and a threat to the “integrity of the union.”

This fraudulent criticism and all of its embellishments—critical race theory is not, in fact, taking over America’s classrooms—are part of the growing Republican furor over the Times’ Pulitzer Prize–winning project, which was conceived by reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones and launched in 2019. The ongoing project “aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of our national narrative.” Its necessity is proven by the conservative backlash to it. Iowa, for instance, was founded on the oppression of Black people. In 1839, Iowa’s first territorial legislature enacted an “Act to regulate Blacks and Mulattoes,” forbidding Blacks or “mulattoes” from settling in Iowa without proof of their “actual freedom,” and Iowa’s 1859 Constitution gave the right of suffrage to “every white male citizen” and only permitted “free, white males” to be members of the House of Representatives.

But such historical truths often don’t make it into K-12 curricula because American education, like American governance, has focused on white lives since our founding. You might even say that we’ve always had race theory in the classroom: the teaching, implicitly and sometimes explicitly, of a white-centric view of history.

American education in the 1800s was pure chaos. Universities prescribed their own requirements for entry, and high schools curated their own curriculum maps, creating anarchy for university entrance procedures. The diversity in admission requirements made it difficult for high schools to prepare their students for college admissions. In 1885, Dr. Cecil Bancroft, principal of Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, complained that “in out of over forty boys preparing for college next year at Andover we have more than twenty senior classes getting students ready for twenty separate colleges.” In 1870, reading English was required for Harvard, while Princeton required English grammar and orthography. Yale required Sallust; Harvard did not.

So in July 1892, the National Education Association tried to bring method and uniformity to America’s education system. It commissioned a “Committee of Ten” to recommend an orderly nationwide system of education. Members of the committee included one representative of public secondary schools, one professor, one headmaster of a girl’s high school, one private school headmaster, one public secondary school principal, and five college presidents. All of them were white.

The Committee of Ten organized nine “conferences” based on subjects the Committee of Ten found to be common in schools: Latin; Greek; English; other modern languages; mathematics; physics, astronomy, and chemistry; natural history (biology, including botany, zoology, and physiology); history, civil government, and political economy; geography (physical geography, geology, and meteorology). Each conference—made up of 10 white men—convened for three days to answer questions such as: At what age should certain subjects and topics be introduced? How many years and hours per week should each course be studied? Should subjects be taught differently for pupils who are going to college?

This project provided the foundation of the K-12 American educational system today. At the end of the nine conferences, the Committee of Ten delivered a report to the NEA with the following recommendations: eight years of elementary education, four years of secondary education, an assortment of electives; all courses should last the same number of minutes, and the recommended programs of study resemble an education with which most Americans are familiar. The power to determine the purpose of education and codify what is worthy of study was wielded by white men, who viewed education through a white aperture.

The Conference of History reported that “general European history has the advantages of offering subjects capable of detailed and intensive study, and of furnishing a contrast to that development of the Anglo-Saxon race which is the main thought of English and American history.” The topics that the Conference of History suggested for a program of study were American history and American civil government; European history (French, Greek, Roman, and English history, specifically).

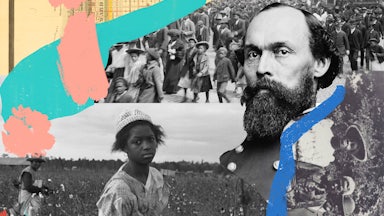

Only 29 years after America abolished chattel slavery, the committee members could not fathom that their Black countrymen had a culture worthy of preservation and study. The lack of Black history or study of the evils of slavery or white supremacy was not an oversight. One 36-year-old member of the Conference of History, a professor of jurisprudence and political economy at Princeton, was a Ku Klux Klan enthusiast and chattel-slavery apologist who believed Blacks were an “inferior” race: future President Woodrow Wilson. Wilson’s interpretation of history was so sympathetic to slavery and the KKK that quotes from his book, History of the American People, were featured in the film Birth of a Nation, which Wilson screened at the White House.

In an 1892 Atlantic Monthly essay titled “The Education of the Negro,” William T. Harris, Commissioner of Education from 1889 to 1906 and chairman of the Committee of Ten, wrote:

Here is the chief problem of the negro of the South. It is to retain the elevation acquired through the long generations of domestic slavery, and to superimpose on it the sense of personal responsibility, moral dignity, and self-respect which belongs to the conscious ideal of the white race. Those acquainted with the free negro of the South, especially with the specimens at school and college, know that he is as capable of this higher form of civilization as in slavery he was capable of faithful attachment to the interests of his master.

The work of the Committee of Ten ushered in a new era of universal liberal arts education for K-12 students regardless of their “destination.” The legacy of the Committee of Ten was progressive, but progress in America is seldom absent of antagonism toward Black Americans. Education has progressed since the early 1900s, but legislation to ban teaching that “one race or sex is inherently racist or sexist” is still a way of antagonizing Black history.

Texas Governor Greg Abbott is a stalwart of this tradition. “To keep Texas the best state in the nation, we can never forget WHY our state is so exceptional,” he tweeted last month. “I signed a law establishing the 1836 project, which promotes patriotic education & ensures future generations understand TX values. Together, we’ll keep our rich history alive.” Abbott’s words echo the Conference on History, which wrote in its 1892 report that “history furnishes the best training in patriotism,” and “Americans know that our country is great, better than we know why it is great.”

On July 16, the Texas Senate passed a bill that would remove the requirements from a new law, H.B 3979, to teach concepts like the immorality of slavery and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a Dream” speech. It also removes references to historical figures of color and women from the curriculum requirements. According to the bill, a teacher who chooses to discuss a “widely debated and currently controversial issue” must try to “explore the topic from diverse and contending perspectives without giving deference to any one perspective”—except if that contending perspective is the 1619 Project, as the legislation forbids a teacher to require an “understanding of the 1619 Project.”

The backlash against the Times’ project and critical race theory is instructive. As Nikole Hannah-Jones tweeted recently, “The fights against the #1619Project have never been about an accurate rendering of history.” The litany of Republican legislation to ban Black-centric narratives is a reverberation of the Conference of History’s intent to train students in a white, “patriotic” view of the past. The right wants students to believe that white Americans, even slaveholders, were redeemable—even ultimately virtuous—purveyors of the American experiment in freedom. They want to preserve a history that forgives and forgets all the wrongs committed in the service of white supremacy. They want to remain the heroes of the country’s history, despite all evidence to the contrary.