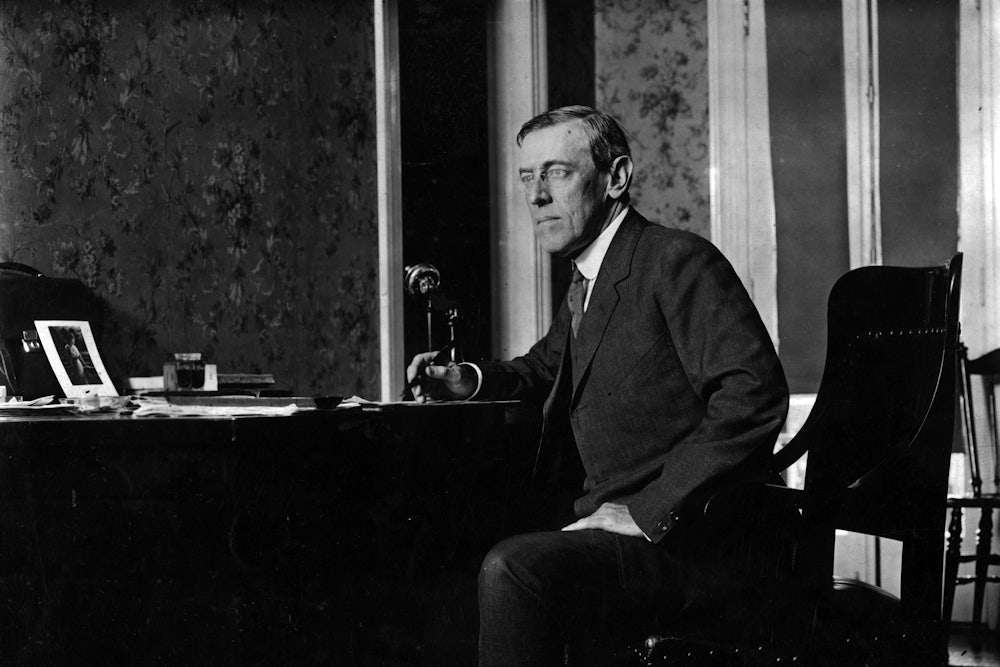

Princeton University’s school of public policy has long been named for Woodrow Wilson, the twenty-eighth president of the United States. But on June 27, the university announced that his name would be removed due to Wilson’s long record of racism. Said the university, “We have taken this extraordinary step because we believe that Wilson’s racist thinking and policies make him an inappropriate namesake for a school whose scholars, students, and alumni must be firmly committed to combatting the scourge of racism in all its forms.”

“Wilson’s segregationist policies make him an especially inappropriate namesake for a public policy school,” Princeton President Christopher L. Eisgruber said. “When a university names a school of public policy for a political leader, it inevitably suggests that the honoree is a model for students who study at the school. This searing moment in American history has made clear that Wilson’s racism disqualifies him from that role.”

This decision was a hard one for Princeton, given Wilson’s deep personal ties to the university and the university’s long ties to the South. Not only was Wilson a student at Princeton, he was a professor there for many years, culminating in his becoming president of the university. As president, Wilson not only refused to admit any black students, he erased the earlier admissions of black students from the university’s history.

For years, Princeton has struggled with Wilson’s legacy. A committee was appointed in 2015 to look at the issue and make recommendations. However, its report said that the name of the Woodrow Wilson School should be retained for the time being. A New York Times editorial at the time said this was wrong and urged the removal of Wilson’s name.

Although Princeton received a great deal of input about Wilson’s record on race, I’m not sure if the university fully appreciated just how racist he had been—especially given that he was not some cigar-chewing Southern politician pandering to ignorant neo-Confederates, but the best-educated president in American history (law degree from the University of Virginia; Ph.D. in government from Johns Hopkins). If anyone knew better, he did.

The explanation is that Wilson was a man of the South. I think many people erroneously believe he was from New Jersey, where he served as governor before becoming president. In fact, he was born in Staunton, Virginia, in 1856. Much of his childhood was spent in Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

Wilson’s father, Joseph Wilson, was an itinerant Presbyterian minister who defended slavery on biblical grounds. During the war, his church was used as a hospital by the Confederate Army, and young Woodrow witnessed General William Tecumseh Sherman’s devastating march to the sea. The Civil War and its aftermath left a deep impression on Wilson for the rest of his life.

Much of Wilson’s professional work as an academic dealt with the Civil War and Reconstruction. He always took a Southern point of view, seeing slavery as relatively benign, militant groups such as the Ku Klux Klan as fairly harmless, and Reconstruction as a disaster.

However, Wilson was very adept, politically. When running for governor he successfully courted black voters, but in office did nothing for them. The same pattern emerged when Wilson ran for president. Even W.E.B. Du Bois was sufficiently impressed with him to give him his endorsement. Later, Du Bois was bitterly disappointed.

Elected president in 1912, only the second Democratic president since before the Civil War, Wilson appeared to be the quintessential Progressive Era leader. But he understood that the South was the base of the Democratic Party, as well as the region to which he had the most affinity. Moreover, the progressive ideology of the era was in many ways quite racist.

Wilson made certain that the South was well represented in his Cabinet, designating Albert Burleson of Texas as postmaster general and North Carolinians David F. Houston as secretary of agriculture and Josephus Daniels as secretary of the Navy. Although Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo was living in New York at the time of his appointment, he was born in Georgia and spent much of his life in Tennessee. In the words of one historian, “The President surrounded himself with men whose racial views were Southern in the narrowest sense.”

At one of the first Cabinet meetings of the new administration, on April 11, 1913, Burleson urged the institution of racial segregation throughout the federal government. Wilson said nothing against it, so Burleson, Daniels, and McAdoo interpreted his silence as constituting permission for them to impose segregation within their departments at their own discretion. No announcement was made of the new policy, but it quickly became known that the Wilson administration was instituting a major modification in the treatment of black workers throughout the federal government from what had been the case under postwar presidents. Historian Kathleen Wolgemuth describes the changes:

By the end of 1913, segregation had been realized in the [Treasury Department’s] Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the Post Office Department, the Office of the Auditor for the Post Office, and had even begun in the City Post Office in Washington, D.C. This involved not only separated or screened-off working positions, but segregated lavatories and lunchrooms.… In the office of the Auditor of the Navy … screens set off Negroes from whites, and a separate lavatory in the cellar was provided for the colored clerks.

In 1914, the Civil Service began demanding photographs to accompany employment applications for the first time. It was widely understood that the only purpose of this requirement was to weed out black applicants.

According to Wilson biographer Arthur S. Link, “Burleson and McAdoo made a clean sweep of Negro political appointees in the South and allowed local postmasters and collectors of internal revenue either to downgrade or dismiss Negro workers with civil service status.” The postmaster in Atlanta fired 35 blacks, and the chief federal tax collector in Georgia said publicly, “A Negro’s place is in the cornfield.”

Blacks were also dismayed by Wilson’s policy of replacing black political appointees with whites in positions blacks had held for many years through Republican and Democratic administrations. For example, the U.S. envoys to Liberia and Haiti, as well as the register of the Treasury, had traditionally been blacks. Wilson replaced them all with whites, denying blacks even the tiniest bit of political patronage. “Negroes not only failed to make progress toward equality in securing patronage … during Wilson’s administration but actually lost ground in their struggle for equal recognition by the national government,” historian George Osborn observed.

“What happened in Washington in 1913 involved more than the growing toleration of petty prejudices,” historian Henry Blumenthal wrote, 50 years later. “Worse than that, trust was violated, and hope was lost.”

After being put off for a year, a delegation of black leaders finally met with Wilson to discuss their concerns in November 1914. The meeting did not go well. According to a New York Times report, Wilson “resented” the attitude of the group, especially its principal spokesman, William Monroe Trotter, whom Wilson said he would never meet with again. The president said he had never been addressed in such an insulting fashion since taking office. He insisted that the segregation policy was for the comfort and best interests of both blacks and whites.

In 1915, blacks were again insulted by Wilson when he arranged for a private showing at the White House of the notoriously racist movie, The Birth of a Nation, based on his friend and classmate Thomas Dixon’s book, The Clansman. Even by the standards of the time, it was over the top in its glowing portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan, and there were many protests against it in Boston, New York, and elsewhere. However, the producers of the film were successful in countering them by pointing to the White House showing, which was attended by Wilson, senior members of Congress, and the Supreme Court. Afterward, Wilson reportedly said of the movie, “It is like writing history with lightening. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”

Sadly, Wilson’s segregation policy lived on after him. Republican presidents of the 1920s kept the races separated in the civil service even though blacks were predominately members of the GOP in those days. Even Democrat Franklin Roosevelt continued the policy, which was only ended by Harry Truman.

Not surprisingly, Donald Trump, the most racist president since Wilson, has come to Wilson’s defense, attacking Princeton for excising his name from its policy school. Conservative columnist Ross Douthat called the university’s decision “fundamentally dishonest” because it was only made under pressure from left-wing activists.

Like removing statues of treasonous Confederate politicians and military leaders, one would have preferred Woodrow Wilson’s racism to have been recognized much earlier. But that is no reason not to act now. Maintaining monuments to reprehensible people and policies out of a misplaced sense of history is foolish and insulting to African Americans who suffered for centuries under slavery and Jim Crow. Princeton is doing the right thing.