It’s about time America became disenchanted with foodies. Pig, Michael Sarnoski’s foodie noir about loss, love, and labor in Portland, Oregon’s restaurant scene, doesn’t leave them much room for redemption. It tells a story that starts with the titular pig who is, however, virtually absent from the film. It is this absence that propels the film’s narrative, which offers a none-too-subtle critique of what counts and what doesn’t in the world of high-end cuisine, baked into a formulaic kidnap-movie plot. Pig spends most of its time sending up the manners and morals of an industry that promises diners real food at premium prices, selling them feel-good stories and ethical peace, all while abusing workers and animals. This is often painfully heavy-handed, but it speaks to a fundamental truth about a troubled industry.

The pig is a truffle pig. The best in the business. When we meet her, she is leading Rob, played by a bearded, unkempt Nicolas Cage, to valuable truffles across a vast expanse of Pacific Northwestern forest. She is, it turns out, his only companion, sharing his Thoreauvian cabin, shoddy and spartan except for the kitchen, which is well equipped enough to cook mushroom-stuffed pastries. The two live their isolated life off the land, but like Thoreau, they are far from self-sufficient. Their livelihood depends on their one link to civilization and, as will be revealed, to Rob’s past: Amir, an ambitious young truffle broker who drives a yellow Camaro and listens to lectures about classical music. When the pig is stolen and Rob assaulted by truffle-hunting junkies—a not altogether unbelievable scenario in rural Oregon—it is Amir who grudgingly offers to take him to the city to find her.

Pig’s Portland feels like an episode of Portlandia as written by Chuck Palahniuk, not least because one of Rob and Amir’s first stops is a sort of perverse underground pugilisim circuit for restaurant staff, where one person can pay to tee off on the other, who cannot defend themself. Rob subjects himself to a flogging in exchange for information about the pig, but in doing so reveals his true identity as Robin, a pioneering chef who for reasons never fully made clear (it may have had something to do with his wife dying, it maybe had something to do with disillusionment) left success and fame behind, but did not leave on good terms. Whatever Robin did to the man who mauls him in that ill-lit basement, à la Edward Norton tenderizing Jared Leto in Fight Club, we are made to feel that he didn’t deserve it.

Pig is a fable. And it is a fable marked by penance, borne by Rob in heartbreak and beatings. With more ham-fisted symbolism, Cage’s character becomes increasingly disheveled and bloody as the movie goes on, never cleaning himself off, even when he stops by an old friend’s humble bakery or an impossible-to-get-a-seat, hyperlocal restaurant. It is here that Rob delivers what will likely be the movie’s most talked-about monologue: a rebuke of the pretentiousness of the foodie scene and its fetishization of the idea of “real food” that, while caricatured by Sarnoski, peppers actual mainstream American food writing and discourse.

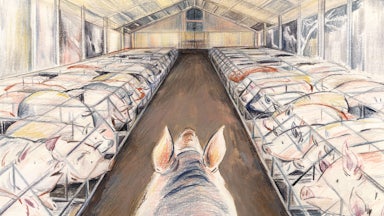

In the movie, as in no-less-obnoxious real-life restaurants, as well as a great deal of foodie writing—think Michael Pollan and Mark Bittman and their literary progeny— there is a fetishization of untainted, unprocessed, artisanal food. Not only is this frequently elitist (who’s actually eating truffles, or hand-slaughtered free-roaming chickens, for that matter?) It also fetishizes in a far more Marxian sense: It focuses on the product itself and not how it actually made its way to the plate. In Pig this is made painfully clear when a white-clad chef launches into a poetic explanation of truffles as local terroir to the very person who digs them out of the ground. What Pig shows through Rob’s increasingly desperate search is the very real supply chain behind the perfectly curated food world, including butchers, waiters, kitchens, and ingredients dug by hand from the earth and peddled by slick entrepreneurs.

Behind the foodie ideal there are real people doing real work, often brutally mistreated and underpaid, making it no different from the conventional food industry it works so hard to differentiate itself from. As the United States ostensibly bounces back from the Covid-19 epidemic, many restaurants are unable to find staff, many of whom could not even qualify for unemployment insurance because their base pay was too low. Many such formerly exploited employees now understandably refuse to return to the industry for unsustainably low pay.

The very ingredients that small-scale foodies rave about are often hard to come by, leading to widespread fraud. That’s as true in the world of artisanal meat as it is in the world of truffles: Most recently, Bay Area foodie darling Belcampo Meats was revealed—fittingly, by a disgruntled employee—to be repackaging conventional meat as if it were humanely, regeneratively, and all-the-restly raised.

Bosses in foodland are every bit as craven and cutthroat as anywhere else. The high-end consumers and the food journalists who support these businesses have started to realize this, thanks to countless exposés and whistleblowing in the past few years—but not before turning monstrous celebrity chefs into cultural icons. Gordon Ramsay abusing an employee by forcing her to call herself an “idiot sandwich” is not only one of the internet’s most recognizable memes but a feather in the cap of Ramsay, who has capitalized on the abuse to coax cheap laughs on late-night TV. The list of chefs lauded by the food media but outed by their abused employees as tyrants, including Mission Chinese Foods’ Danny Bowien and Fat Rice’s Abe Conlon, is a long one. Rob, we are led to believe, was exactly this sort of abusive superchef. In this sense, while Pig may read as pastiche, it also certainly picks the right villain: Darius, a sociopathic foodie impresario who acts as the link between the real work of food production and the appearance of breezy epicureanism at Portland’s froufrou eateries.

This whole world, based on fetish of the local and real, is itself not real, says Rob, straight-faced, bloodied. Even the customers who fancy themselves gourmets are implicated: In addition to being end consumers in value chains that, while labeled “local,” can be filled with exploitation and fraud, these high-end diners are also rubes. All of this echoes the very real story of the Pacific Northwest’s infamous destination Willows Inn, where fake ingredients and “racist, sexist and homophobic slurs” aimed particularly at female kitchen staff, were par for the course behind the $500-a-night real food experience sold to diners.

If there is something worth salvaging from the foodie world, the movie seems to suggest, it is the act of cooking and the pleasure of eating itself, freed from pretension and the drive for profit, be it the mushroom pastry from the opening scene or the intricate meal of its climax. But to hear Rob tell it, it is precisely this kind of experience that, once packaged and price-tagged, becomes devalued. This is all very melodramatic, of course. (One can’t help but think of Fight Club again and Edward Norton’s pop-Marxist call to look at the emptiness behind the veil of imperfect-on-purpose consumer goods, “crafted by the honest, simple, hard-working Indigenous aboriginal people of wherever.”) But it’s not untrue.

Value and who gets to decide about it is a theme that runs through the movie. “You have no value,” an old acquaintance tells Rob at one point. It also applies to the women in the movie, reflecting the gendered dynamics of the Michelin-star world but also the sausage party that is the cast. Women are virtually absent, appearing as minor characters or, like the pig, as absences: Rob’s dead wife; Amir’s almost-dead mother; the tragic Greek characters Hestia and Eurydice, after whom restaurants are named. After the past few years of sexism and harassment scandals in the food world, this depiction feels cruelly apt.

All of these thematic ingredients come together in the pig. Her disappearance, we find out eventually, is a matter of familial and business judgment of what is valuable for whom. Consistent with the instrumentalization of animals in the American food system, including in the meat-forward world of the foodies, most characters in the film see the pig’s disappearance as a matter of Rob being deprived of a source of income or a tool or, perhaps, a pet, something with economic or sentimental value. On more than one occasion, he is offered money to replace her.

But this is not what the pig is to Rob. She is the one thing in the movie that has no instrumental value to anyone. She isn’t even a truffle pig. Rob doesn’t need her to find the fungi, he eventually reveals to Amir. He needs her as a companion, as interspecies kin. “I love her,” he confesses in a scene that, acted or directed any differently, might have been comical but instead is heartrending. There are no happy endings, here, only brief moments of respite, like a fine meal well cooked.

Pig is set in the world of foodies, but it is an Americana fable with a much broader moral: It’s all bullshit, except for the things that aren’t. Look for those things and cherish them. They don’t last. There’s a practical lesson here, too: Reforming the food business, starting with better protections and wages for labor in haute cuisine and fast food alike, couldn’t hurt, either.