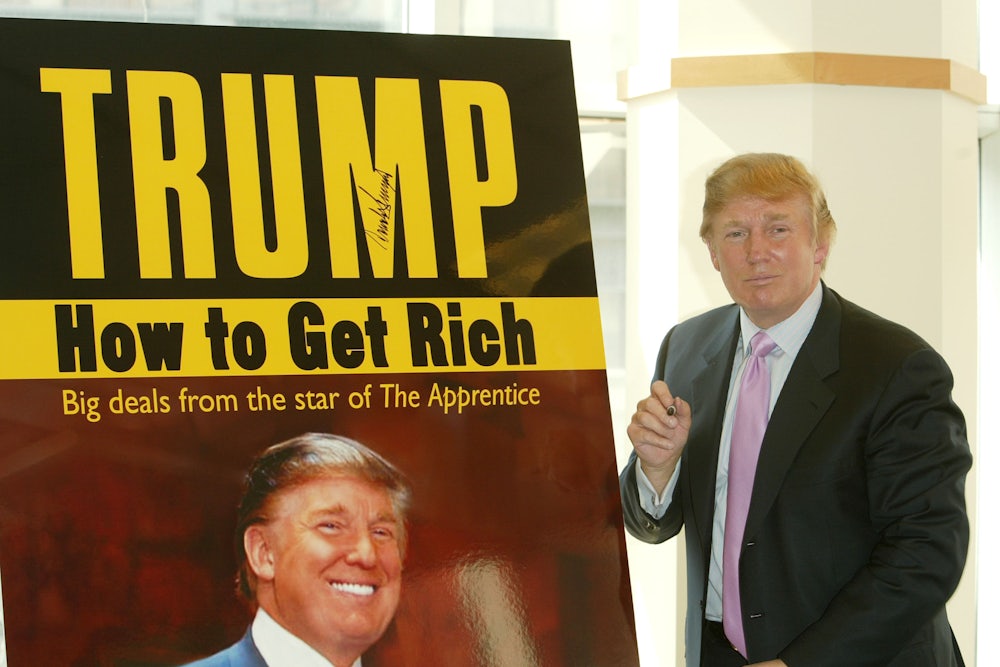

On Friday, Donald Trump released a statement that was odd, even by his own demented standards. Unprompted, the former president informed the public that he was working on “the book of all books” but that he had “turned down two book deals, from the most unlikely of publishers”—presumably large, prestigious, New York City–based firms—because he just didn’t feel like going that route at the moment. The statement concluded with Trump teasing yet another unspecified project, which he described as “much more important” than the previously touted “book of all books.”

What was Trump really up to? It’s possible his outburst was sparked by a little touch of jealousy: Trump is reportedly peeved that Mike Pence inked a substantial deal from Simon & Schuster, which had published Crippled America, the most recent of The Donald’s literary offerings, in 2015. But it may also have simply been Trump’s latest attempt at ginning up interest from publishers in some new postpresidency book. Days after his election loss, people close to Trump (if not Trump himself) were claiming he was being “bombarded” with potential book offers that were supposedly worth upward of $100 million, a number conveniently higher than the one Barack and Michelle Obama were given for their books in 2017. Given the fact that what has materialized since those heady days amounts to bupkis, one can only assume this was Trump’s first desperate attempt to start a bidding war for a book no New York publisher seems to want.

If New York’s largest publishing houses were hesitant to publish Trump in the immediate aftermath of the 2020 election, as I and others reported last November, there’s virtually no chance that a “Big 5” publisher will be willing to take him on after the Capitol insurrection. As The New Republic first reported, Simon & Schuster’s Jonathan Karp told his staff at a town hall meeting last month that the company wouldn’t be publishing the former president. On Tuesday, Politico surveyed the Big 5 publishers and reported that “none of the sources said they had heard about such potential book offers, and most said they wouldn’t touch a Trump project when he does start shopping a book around.”

None of this is especially surprising. And there hasn’t been anything in recent months that might get the Big Five to reconsider their decision or make them less wary of working with Trump. The former president’s short-lived “blog,” for instance, did not hint at the possibility that he had any deeper insights or observations, drawn from his time as the “Leader of the Free World,” to offer the world; it instead largely consisted of nutty conspiracy theories about how the election was stolen from him. It’s hard to escape the strong impression that any book he might produce would focus heavily on these kinds of lies, a third rail for any respectable publisher. Simon & Schuster dropped Josh Hawley for his role in the insurrection; there’s simply no way a Big 5 publisher would work with an unrepentant Trump.

What is new is how publishers are justifying the decision not to work with an ex-president, an unprecedented move in recent history. Apart from presidents who either died in office or were incapacitated shortly thereafter, every American president over the last century has published a book with a major house; William Howard Taft was the last ex-president not to write a memoir about his time in office.

For this ex-president, however, publishers recite simple, defensible narrative: A Trump book would not be truthful and would be impossible to fact-check. “It would be too hard to get a book that was factually accurate, actually,” one “major figure in the book publishing industry” told Politico. “That would be the problem. If he can’t even admit that he lost the election, then how do you publish that?” In a recent town hall meeting, Karp told staffers Simon & Schuster wouldn’t publish Trump because he couldn’t be counted on to write an accurate book about his time in office. (Simon & Schuster has, however, recently inked deals with Vice President Mike Pence and former senior adviser and connoisseur of “alternative facts” Kellyanne Conway.)

This is an anodyne defense, but it’s a telling one, especially in the context of conservative publishing. Books are famously not fact-checked—the standard practice at Big 5 imprints is that fact-checking is optional and must be paid for by the author out of pocket. And while outright fabulism in the vein of a James Frey or Jonah Lehrer will get a book pulled, the idea that publishers have a strict code of accuracy, let alone a set of journalistic ethics, simply doesn’t track. In the more respectable corners of publishing, the editing process involves a fair amount of rigor and fact-checking. But there are all kinds of corners in which looser standards are applied, and that is particularly true when it comes to conservative books and books by politicians.

During the conservative publishing boom of the 1990s and the 2000s, book publishers were more than happy to have right-wing, hyperpolitical imprints churning out garbage because that garbage was highly lucrative. As Timothy Noah wrote in Slate in 2008, “Simon & Schuster and the other big publishing houses have started conservative imprints, at arms’ length and with noses held, because they recognize them to be a gold mine.” These publishers, Noah continued, understood that “conservative imprints aren’t required to adhere to the same standards of truth as the grown-up divisions.”

During this same period, there really wasn’t a left-wing equivalent of these publishers—though it’s certainly true that your typical Big 5 imprint has a distinct liberal leaning. (Interestingly, a left-wing equivalent of conservative publishing did emerge during the Trump era, but it appears already to be dormant again.) But dubious works of history and politics from writers like Dinesh D’Souza and Jonah Goldberg represented the more reputable part of these publishers’ work. An adherence to fact-checking beyond a book authored by Donald Trump would, as I argued last year, call into question mainstream publishing’s entire conservative publishing apparatus.

It’s certainly true that Trump’s lying carries world-historical import, but there’s more going on here than concern over factual accuracy. There is some irony here. A Trump memoir would have incredible commercial potential—and would likely sell hundreds of thousands of copies, at the very least—but only if it was truly bombastic and chock full of lies. That, and that alone, is what his audience is fiending for; in all likelihood it’s what his most ardent critics want, as well. Publishers have, perhaps conveniently, concocted a condition that is appealing neither to them nor to Trump. Donald Trump could never produce an accurate book, thus they could never sell one.

The point about the truthfulness of Trump’s hypothetical book is, most likely, more of a fig leaf than a justification. Publishers are more afraid of revolts from staffers, authors, and bookstores that could ultimately cost them more than they might gain by publishing a million-seller from Donald Trump, both in terms of money and reputation. (Simon & Schuster has already taken a reputational hit just for signing up Pence and Conway.) Every publisher knows the shitstorm they would kick up, both internally and externally, if they handed Donald Trump a book deal and a fat check, regardless of what strings were attached. They have decided they want no part of it.

That’s not to say that a publisher won’t emerge. Regnery, the independent conservative imprint that picked up Josh Hawley after he was dropped by Simon & Schuster, is one possible home, though there are several smaller, conservative presses that would love to go into business with Trump. Self-publishing is also an option, and Trump would have no problem distributing a book in stores without a traditional publisher. But Trump’s own vanity and hunger for acceptance from Manhattan’s cultural elite make such a move unlikely, even as a last resort. And then there’s money: Trump is clearly in the hunt for something in the range of what President Obama got, but that simply isn’t going to happen. He could cook up a profit-sharing deal with a smaller publisher or rake in huge margins by self-publishing, but neither option would allow him to say he got a bigger advance than Barack Obama.

Trump, meanwhile, is convinced that the commercial appeal of his book will outweigh all of this. In a statement to Politico on Monday, he insisted that he was writing a book and that publishers were desperate for it. “If my book will be the biggest of them all, and with 39 books written or being written about me, does anybody really believe that they are above making a lot of money? Some of the biggest sleezebags [sic] on earth run these companies.” That might be true, but it might not be true enough.