Plenty of Hollywood auteurs can claim a Freudian dimension

to their work. But how many ever met the great man himself? When Oscar-winning

director Billy Wilder was 19 years old, he was making a living in the rackety

world of journalism in Vienna. He wrote for Die

Bühne and Die Stunde, composing

crosswords, squibs, columns, gags, movie reviews, theater reviews, interviews,

anything and everything. In those days, his byline was Billie Wilder (he

changed the spelling when he moved to Paris and decided “Billie” was a girl’s

name); the surname was pronounced “vilder,” rhyming with “builder.”

He haunted Vienna’s café scene and wrote in a snappy version of the distinctively European manner termed feuilleton (the word survives in today’s German newspapers for their arts sections). It was the style of writing you’d find in that part of the publication languidly perused by the discerning literati in cafés: the reviews, the critical essays, and the personal musings. Wilder himself rhapsodized about café culture: “Coffeehouses have something in common with well-played violins. They resonate, reverberate and impart distinct timbres.”

In December 1925, Wilder’s editor told him to go to Sigmund Freud’s house at Berggasse 19 and ask him what he thought about the growing phenomenon of fascism, without any sort of arrangement or appointment—an ambush-interview that the British tabloids call “monstering” someone. So young Wilder—whose 1950 movie Sunset Boulevard was to feature the most famous Oedipal relationship in movie history, between aging silent star Norma Desmond and young screenwriter Joe Gillis; and whose 1959 comedy, Some Like It Hot, would show the fluidity of identity (“I tell ya, it’s a whole different sex!”)—rang the bell and asked the maid if Dr. Freud was at home. Sigmund Freud appeared, with a napkin around his neck; Billy Wilder had the bad taste to interrupt his lunch. Freud ignored his proffered business card and curtly told him to be on his way.

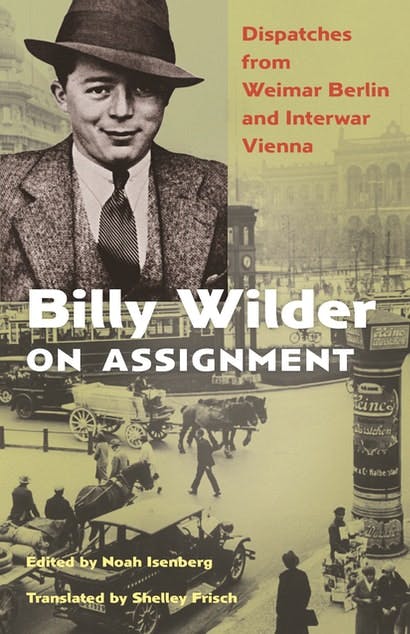

Sadly, Wilder’s own write-up of this aborted interview does not surface in Billy Wilder On Assignment, a richly enjoyable and atmospheric selection of the director’s journalistic writings in Vienna and later in Weimar Berlin, edited by Noah Isenberg and translated from the German by Shelley Frisch. In interviews, Wilder later also remembered putting the same question about fascism to Alfred Adler, Richard Strauss, and Arthur Schnitzler as part of a general article. Sometimes he claimed to have spoken to all four on the same day. Was the article abandoned? Lost? Was he exaggerating or even inventing? I don’t think so: The very fact that Freud had nothing to say argues in Wilder’s favor. Wilder the fabulist would be unable to resist a pithy quote.

The journalistic work of Billy Wilder in Vienna and Berlin

paints an amazing picture of improvisation and survival, excitement, cheek, and Schnauze. This was a young man who, with

nothing much in the way of formal education, made a decent living in

journalism and then, by cultivating a side hustle in screenwriting, created the

parallel career in the movies that was to be his ticket out of the European

inferno. This thrilling and valuable book lets us see the European roots of a director who made so many classic American movies, and how they were shaped in

the tumult and horror of the twentieth century.

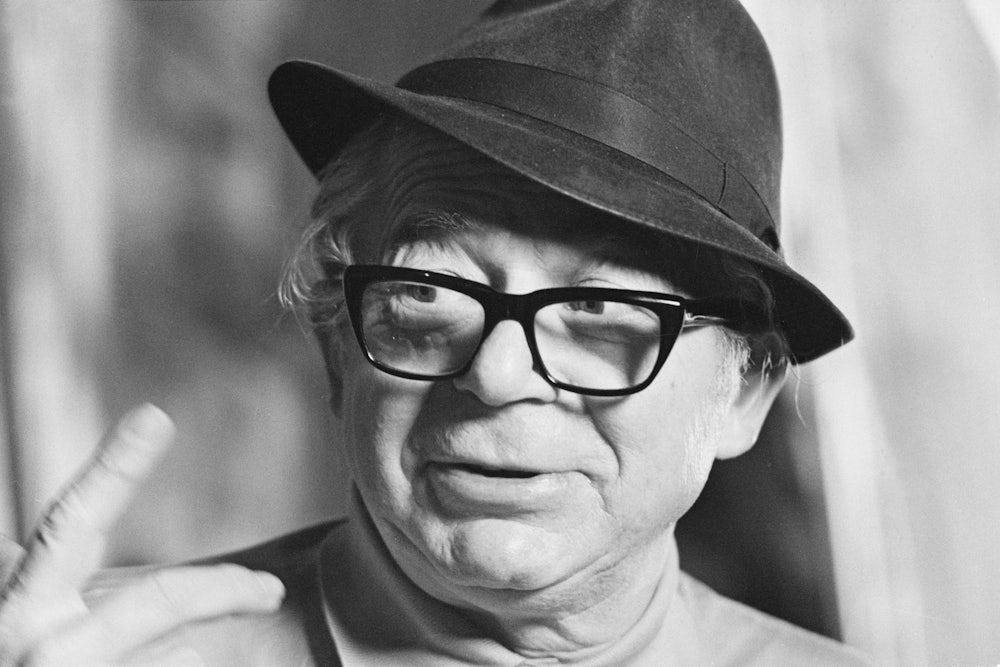

In Vienna, Wilder’s crowning achievement was to interview jazz titan Paul Whiteman. Already affecting the rakish hat that stayed with him all his adult life, he got embedded in Whiteman’s entourage when he and his orchestra traveled on from Vienna to Berlin. Wilder stayed on in Berlin, one of the most important movie industry cities in the world. It was from Berlin in the early 1930s, seeing how Nazism was to take over Germany, that Wilder joined the Jewish exodus, heading first for Paris and then, when Columbia Pictures bought his script for a comedy caper called Pam-Pam and even offered to pay the boat fare, Wilder sailed for Los Angeles. Wilder’s father had died in Berlin on a visit to his son. But his mother, grandmother, and stepfather remained behind in Austria. All were murdered in the camps.

Wilder’s journalism shows us the European roots of Americana, and of course the colossal enthusiasm for America—the Amerikanismus—that was everywhere in Berlin and Germany in the late 1920s and early ’30s, an association annulled by the grim nationalist diktat of Hitler and then effaced in the cultural memory by the fact of America and Germany’s enmity in World War II. Wilder adored the American reportage of his great journalistic mentor in Berlin, Egon Erwin Kisch, who published his account of U.S. travels in a tone of ironized infatuation as Paradies Amerika. Wilder naturally reviewed Hollywood movies, including ones from his own future stars Gloria Swanson and Erich Von Stroheim. Wilder the critic is dismissive in these pages about Von Stroheim’s much-cherished, much-cut masterwork Greed: “lopsided and full of meaningless symbols.” Did Von Stroheim ever see that review? Did Wilder ever dare mention it to him when they worked together?

It is in 1929 for the Berlin paper Tempo, that Wilder mentions the taste of a wildly fashionable new drink that would still have been unfamiliar to his readers: “Coca-Cola, which tastes like burnt tires. But it is said to be very refreshing.” (Later, in Wilder’s 1961 movie One, Two, Three, James Cagney was to play a Coca-Cola executive in Cold War Berlin.) Like so many European incomers to the United States, Wilder brought with him something that is often overlooked in histories of prewar immigration—an existing passion for America, whose cultural life Europeans naturally invigorated and reinvented with their own experience and expertise. You could read Wilder’s journalism as part of the pre-history of America, or maybe it is that you could read his movies, particularly his comedies, as a post-history of Europe—the styles and talents of Europe, extensively assimilated and normalized in America’s safe prosperity and freed from the tragic horror of European history.

In Vienna, Wilder’s most breathless and most excitable journalism centers on the arrival of the Tiller Girls on the train at Vienna’s Westbahnhof—a naughty-but-nice English female dance troupe, known for their saucy high-kicking routines. He writes: “These are the Tiller Girls, the charming Lawrence Tiller Girls from Manchester. Everyone is chirpy, busily squealing and giggling. You don’t know where to look first. Sixteen magnificent girls, gathered together, cultivated in all parts of the world. Those figures, those legs, those little faces, and well-bred to boot; aristocratic you might say.” Some Like It Hot was of course remade from a German film called Fanfaren Der Liebe (itself remade from a French film), but Wilder was clearly, ecstatically remembering something from his own past.

His big break in Berlin came when, desperate for cash and as yet without journalistic contacts, he took a job as a dancer-for-hire at the Hotel Eden, one of the tuxedoed young men dancing with married ladies, while their bored, portly husbands sat it out. As Wilder reports in the Berliner Zeitung Am Mittag:

Table 91. An older lady in a bottle-green dress, with a long neck and hair the color of egg yolks; and a little lady, whose reddish snub nose is trying too hard to look uppity. I stand in front of them, a second Buridan’s ass, sweat on my brow, showing all my colors, helpless and wobbly. Then I mechanically thrust my torso forward, toward the one with the snub nose, purse my lips and say very softly: ‘May I ask for this dance…?’ … The little one gets up, places her chubby arm around my shoulder. We dance.

It could be a Wilder movie.

As good fortune would have it, one of the seated husbands was the poet and novelist Alfred Henschke (pen-named “Klabund”), who was amused by young Billy Wilder gallantly guiding his wife, stage star Carola Neher, around the dance floor; he struck up a conversation and encouraged Wilder to write up his account, which was to be the cornerstone of his Berlin journalistic life and the most substantial and cinematic of the pieces collected here. (As for Carola Neher, she divorced Henschke, went to the Soviet Union in 1934, where she was eventually to be denounced as a Trotskyite, and died in prison in 1941.)

Wilder doesn’t mention fascism in these pages. His journalism doesn’t register it. Maybe that isn’t too surprising. Berlin itself was the city most resistant and indifferent to Nazism at the time. In some ways, Wilder’s journalism is the epitome of Weimar Berlin: though not in that decadent and specious style that we have all learned to recognize from the movie Cabaret. Wilder’s journalism is not in denial exactly, but it defiantly offers an alternative to the ugly new extremism. His writing is intent on not giving fascism the oxygen of publicity or the time of day.

He is jaunty and funny and cordially cynical with the rhythms of the born entertainer—something like a 1930s incarnation of Fran Lebowitz. Wilder often sought out a kind of metropolitan innocence, perhaps most characteristically in this novelistic sketch for the Berliner Börsen Courier, called “Berlin Rendezvous,” in 1927—a reverie about where men and women meet up for a first date in Berlin: “the Kranzlerecke, the famous street corner on Kurfürstendamm, the Berolina in Alexanderplatz, and the Normaluhr, the oversized clock at the Zoo railway station.” This last, in fact, is a key location for the 1930 movie he wrote: Menschen Am Sonntag (People On Sunday), an experimental narrative of ordinary people’s “urban pastoral” experiences in Berlin on the weekend. That is the “reality” toward which Billy Wilder’s journalism gravitated.

Or is it? The most brilliant piece in this collection is Billy Wilder’s short story “Wanted: Perfect Optimist,” again published in the Berliner Börsen Courier in 1927, a fiction with something of Gogol or Kafka. It is set in New York and is about a man who answers a job ad and finds that his employer will pay him handsomely for doing nothing other than smiling. He has to just sit in the chair and smile—but his mouth must never relax from a convincing smile the entire working day. It is desperately hard, but he keeps fanatically smiling. Finally, his boss confesses that he has been crookedly selling moldy food and he needed a jolly optimist in the office to boost his brazen confidence: “When I see you, nothing can go wrong, nothing!” But when the man comes into the work the next day, the office door is chained with a notice: “Closed down for bankruptcy.” Did Wilder, in this story, foresee the endless, fatuous smiling optimism that preceded the Wall Street crash of 1929 or Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 and the drumroll of impending spiritual bankruptcy? Either way, when Billy Wilder boarded the RMS Aquitania in 1934, bound for the U.S., he was nursing his own, doggedly persistent kind of optimism.