Entry #203 in the Dylan to English Dictionary, billed by author A.J. Weberman as “the most useful and authoritative translation of Bob Dylan’s poetry you can own,” provides the Dylanological definition of garbage as: “Empty talk, vacuousness, inferior work produced by other artists.” And Weberman, who lays claim to coining the word Dylanology, knows garbage. In the early 1970s, he was infamous for sifting through the trash cans outside Bob Dylan’s Greenwich Village apartment. Weberman was rummaging for clues, angling to unlock the mysteries of his idol: discarded song lyrics, intimate letters, something. What he mostly excavated, according to a 1971 Rolling Stone profile, amounted to “a mound of dog crap and a mountain of odoriferous, soiled disposable diapers.”

Like many in the early 1970s, Weberman saw his hero as an apostate, who had forsaken his role as the voice of a generation. He engaged Dylan with open hostility, lurking outside his house and drawing him into a series of belligerent (and highly entertaining) phone calls. Weberman subjected Dylan’s lyrics to microscopic close readings and played his records backward to reveal hidden meanings. Weberman’s Dylan to English Dictionary is a similarly demented project: the result of ingesting every word of Dylan’s songs into an early computer using punch cards, to find a way into those famously impenetrable lyrics. The results may be wholly cockamamie. But the undertaking itself illuminates so much of Dylanology, a discipline animated by the shared belief that Dylan needs to be deciphered. The mission of the Dylanologist is to serve as codebreaker, or some augur of the divine.

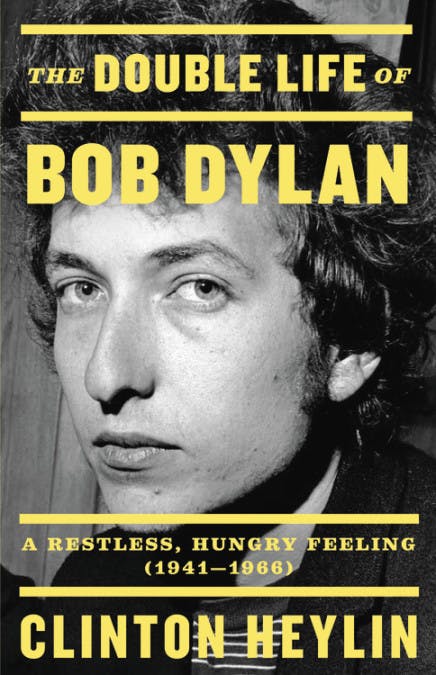

If Weberman was written off as an unhinged oddity in the ’70s, he’s an absolute pariah now. He has spent decades propagating phony theories that Dylan has AIDS (contracted from a dirty heroin needle) and, more recently, that Bob Dylan has died, a casualty of the coronavirus pandemic. Yet the discipline he invented lives on and is now serious business. There’s no mention of the disgraced dean of Dylanology in The Double Life of Bob Dylan: A Restless, Hungry Feeling (1941–1966), the first volume of a new biography by Clinton Heylin, whose own body of Dylanological research numbers eight books, including the thrice-revised biography Behind the Shades and a multipart analysis of each of Dylan’s 600-plus songs. Weberman’s Dylanological preeminence can, by now, be safely disavowed.

Certainly, Heylin sets out to elbow past all other comers, making bullying attempts to clear the crowded field of Dylan researchers, biographers, and armchair obsessives. Ian Bell’s Dylan biographies are “pseudo-historical.” An introduction to a book of Dylan photographs written by august rock journalist Dave Marsh is “insipid.” Longtime confidant Victor Mayamudes’s Another Side of Bob Dylan is “thin gruel.” The online resource About Bob Dylan proves only “ostensibly reliable.” Dylan’s own 2004 memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, is “unreliable,” something that even rookie readers took for granted at the time of publication. Readers are meant to be humbled before such pomposities. Here comes Clinton Heylin to hew a path through the trash heap of vacuous biographies and inferior works. Something is happening here, and this guy—and only this guy—knows what it is.

Heylin’s book arrives at an opportune time. Bob Dylan turned 80 this week. Last year’s Rough and Rowdy Ways album received the sort of universal critical acclaim that has eluded Dylan in recent decades: a welcome (and frankly relieving) reminder that his genius could still find purchase as he entered his ninth decade. He also made headlines for striking a blockbuster deal with Universal Music, which purchased Dylan’s robust back catalog for an undisclosed sum (rumored at about $300 million). Between such big-ticket accounting, and the recent work’s mournful, in places downright funereal tone, it’s hard not to be reminded that Bob Dylan will not be here much longer and is, as they say, “making arrangements.”

There’s also the matter of Dylan’s personal archives—a massive data dump of notebooks, contracts, manuscripts, films, tapes, and correspondence—being sold off to the University of Tulsa in 2017. Heylin’s new research draws heavily from this collection. More than a conventional, or conventionally readable, biography, A Restless, Hungry Feeling feels more like a hefty appendix to extant Dylan bios, or an advanced research seminar in Dylanology. Heylin lays out his own project a little ghoulishly, declaring it “a new kind of biography written in the same milieu as its subject but with the kind of access to the working process usually possible only after an artist’s death.” In his music and presentation of himself, Dylan has always been mercurial, recalcitrant, unknowable: a wiggly mess of creative impulses that Heylin hopes to pin down, playing the Dylanologist as lepidopterist.

At the risk of dismissing the whole venture out of hand, I can’t help but wonder how useful this is. First of all, there’s a simple matter of credibility. Heylin, like anyone who cares even a little bit about Bob Dylan, takes for granted that his subject is a master fabulist, if not a compulsive liar. From his made-up name to his imagined backstory, to his preternatural ability to mimic folk and blues forms that Heylin describes as “uncanny,” the “real” Dylan has always seemed like a bit of a phantasm. This idea, of Dylan telling truths from behind a mask, is productively mined in his 2019 collaboration with director Martin Scorsese, The Rolling Thunder Revue—an entertaining conflagration of tour doc and playful fabrication that Heylin waves away as mere “mockumentary.” If this penchant for fabulism is so deeply baked into Dylan’s DNA, then why should anyone reasonably expect that his private manuscripts or personal letters would adhere any more to the capital-t Truth?

Dispelling Dylan’s various myths, self-styled and otherwise, also has a diminishing effect. It’s like explaining a magic trick. Throughout his career, Dylan’s identity mutated—from warbling folkie to motor-mouthed rock poet to country troubadour, Christian evangelist, and beyond—as he followed his muse, or his whims, or whatever. He defies expectation and seems creatively beholden to not much beyond his own shifting fancies. I imagine this is why most people like Bob Dylan. Because this is why I like him. And if other people like him for other reasons? Well, then that only certifies his status as the man of manifold possibilities, a Bob for all seasons. Rifling through old letters and contracts for clues to the “real” Dylan can feel a little beside the point, like fact-checking The Iliad against archaeological excavations from ancient Greece. Does Heylin expect to find some smoking gun, a scrawl in an old journal reading, “I am going to make a point of performing my identity, to vex and frustrate the public, and particular critics and biographers?” Such a po-faced confessional seems unlikely, and Heylin knows it. Even the titular “double life” conceit of these new biographies seems insufficient for an artist who recently boasted of containing multitudes.

Heylin’s book betrays the frustration of this knowledge. It’s riven with the sort of nastiness that marks first-rate obsessives, whose interest in a subject calcifies in time into a thinly veiled hatred, as the object of their affection fails to reveal its fullness. (A few years back, I was amused by a conspiracy maintaining that The Beatles did not, in fact, exist at all. For such true fanatics, obliteration becomes a form of ownership.) The feeling that Heylin is spoiling his subject is compounded by the author’s writing, which has its own curdling effect. It’s not long before Heylin’s parenthetical corrections of quotes and typos, and his excessive deployment of “[sic]” seem like little more than rank pedantry. His persistent use of locutions such as “learnt” and “’twas” and “knew not” is grating in its pretension. Ditto his reference to a 2011 auction block of Dylan manuscripts as “mouth-watering fare.” Never missing an attempt to diss Dylan’s half-remembered, half-imagined memoir, Heylin repeatedly refers to Dylan as “the Chronicler.” Not since a 2013 Metallica biography habitually identified drummer Lars Ulrich as “the Young Dane” do I recall being so twitchily irritated by a cutesy diminutive.

A pervading sense of mean-spiritedness is never far from these pages. That tone is most obvious in the author’s chary regard of his icon. There is persistent air of suspicion, as Heylin develops the image of Bob Dylan as a “Mr. Hyde, a boozer and pill-popper and womanizer,” who would alienate friends and loved ones as he sculpted the popular persona of an “alter-Dylan.” Yet how suspect is this turn, really? As Dylan moved from folk darling to proto–rock star—realizing, per Heylin’s anguished verbiage, that “his preordained role was to tie a lover’s knot around the red, red rose of folk-rock and rock ’n’ roll’s thorny briar”—he became “public property.” If a Pynchonian abstention from public life was, by 1965, pretty much impossible, then Dylan did the next best thing. He recast himself as an obstinate enigma, quarreling with nosy journalists (merely “frustrated novelists” in his estimation), foiling folknik audiences with his played-way-too-loud rock music, and trolling The Beatles. (Heylin recounts the first encounter between the two most important pop acts of the 1960s in hilarious detail, describing Dylan answering the phone in the Fab Four’s NYC hotel suite with “This Is Beatlemania here.” Whether such antics are snide or hysterical likely boils down to personal taste.) If Weberman’s Dylanophilia was openly combative, Heylin’s has soured into sniping and cattiness. He writes about Dylan like a posturing pickup artist negging for attention.

Still, Heylin’s claim to be king of Dylanologists may well be apt. If nothing else, A Restless, Hungry Feeling serves as the literary equivalent of being stuck at the bar next to a Dylan Guy: the sort of superfan who bores with tedious trivia and is all too eager to correct any half-formed opinion offered by the more casual listener.

Heylin’s subsequent volumes, and their marshaling of the Tulsa archives, may prove more fruitful, if only for rounding out the history of periods in Dylan’s career that aren’t so exhaustively diarized. However revisionist its approach, A Restless Hungry Feeling can’t help but slog across land well trodden. Even casual fans are likely familiar with the highlight reel of Dylan’s mid-’60s apostasy: going electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, being decried as a “Judas” during a 1966 concert in Manchester, etc. Let’s see lengthy fact-checks on the story of Dylan performing all of Blood on the Tracks solo for Graham Nash. Or six pages on the time he played a harmonica in the wrong key on Letterman. Where’s the tell-all of Dylan’s little-seen 1987 film Hearts On Fire, directed by the guy who made Return of the Jedi?

Dylan’s mid-’60s run has already merited intense focus. Scorsese’s 2005 doc, No Direction Home, which runs three and a half hours, also wraps in 1966. Greil Marcus, likewise, has dedicated an entire book to 1965’s “Like a Rolling Stone.” This investment makes sense. Dylan’s shape-shifting in this period spoke not only to the fluctuations of popular music taste but the whole world. The so-called youth culture was aging out of blue jeans and bubblegum and making new demands of the world. Dylan once said of Woody Guthrie, “You could listen to his songs, and actually learn how to live.” For the generation following in the heels of the beats and the folkies, Dylan’s music proved similarly life-affirming.

A Restless, Hungry Feeling ends teasing Dylan’s fateful motorcycle wreck in the summer of 1966, “when he went for a spin on his cherished Triumph, and nearly met his Maker.” It’s a common fork in the understanding of Dylan’s career. It marked the end of a period of rabid productivity that birthed Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde—a remarkable trifecta of records that stand as the apogee of Dylan’s trademark impenetrability, lyrically and otherwise. Some claim the crash also changed Dylan’s vocal timbre, or even that it snuffed out some divine spark of inspiration flickering within him that would never burn as brightly again. It also marked Dylan’s withdrawal from society. It would be eight years before he would tour again, during which time he cultivated what The New York Times termed the “jealous protectiveness of his privacy” and “the legend of a mysterious recluse.”

Heylin’s book speaks to how attentive Dylan has always been to this legend. Raised on rock ’n’ roll, he was a product of celebrity culture and ambassador of the emerging form of popular music. With an intuitive understanding of stardom and its wages, he defined the times by keeping half a step ahead of them. Like another New York City transplant of the era, Andy Warhol, Dylan was preternaturally hip to the idea that an artist’s real art was himself. Beyond his forbidding talent as a songwriter and composer, Dylan was smart. And savvy. And funny. And always desperate, as he told the Toronto Star’s Robert Fulford in 1965, “to get rid of some of the boredom.”

Dylan’s music, at least in the uberproductive interval described in Heylin’s new volume, spoke in a way that was universal and nonspecific. It’s as generous as it is impregnable in affirming different lives in different ways. If Heylin or any other biographer finds something sneaky or duplicitous, or underhanded, or otherwise Mr. Hyde-like about this, it may speak more to their character than it does to Dylan’s. Because, as Dylan once snarled in a testy telephone exchange with A.J. Weberman, the greaseball granddaddy of Dylanology and still the artist’s only worthy nemesis, “I’m not Dylan. You’re Dylan.” The rest, Dylanologically speaking, is garbage.