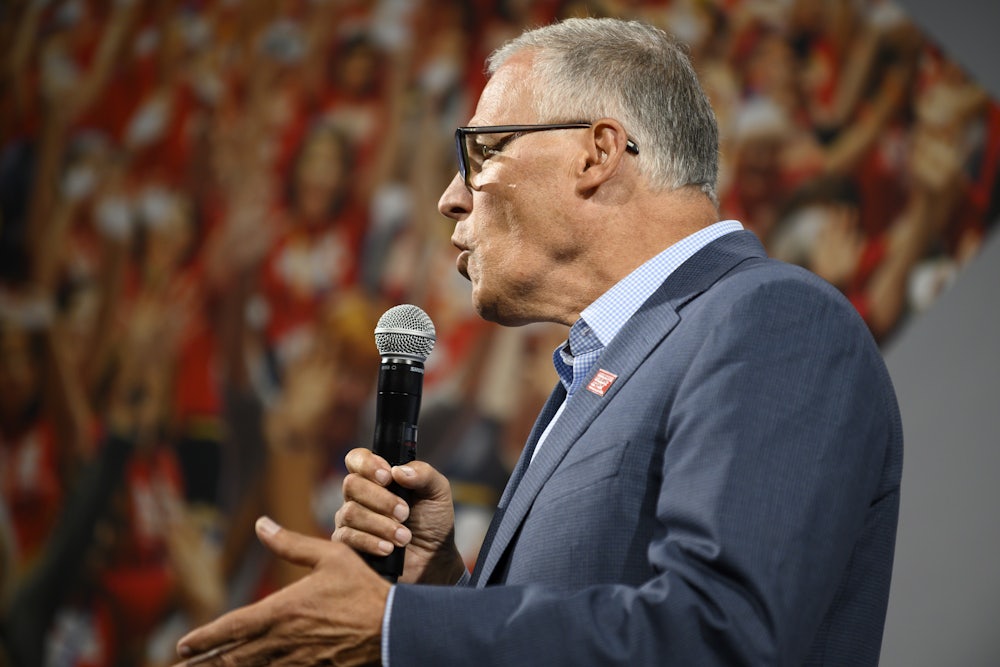

Last week, Washington Governor Jay Inslee signed into law a series of historic climate-focused bills. The new measures included limitations on single-use plastic and styrofoam; a hard cap on carbon emissions and a clean fuels standard; and, maybe most ironically in hindsight, the establishment of an environmental justice council. In a different world, the series of public signings would have been universally praised by the parties who spent the past year championing the bills through the state legislature. Instead, the focus has been on the policies the governor chose to exclude at the last minute.

Tucked down at the very bottom of the announcement heralding Inslee’s signing of these bills was a single sentence: “The governor also signed partial vetoes for sections of HB 1091 (veto) and SB 5126 (veto).” The latter of the two bills, SB 5126, was also known as the Climate Commitment Act. The Climate Commitment Act was the first successful piece of state legislation to establish a net-zero carbon emissions goal of 2050, albeit with an offset market designed to please the polluting powers that be at BP. But it was also crafted to address the state’s existing consultation process with the 19 tribal nations that hold lands in the state, particularly with regard to sacred sites and burial grounds. Consultation is the process by which state agencies must meet with tribes affected by upcoming development projects to ensure that any environmental, cultural, economic, or religious concerns or issues raised by affected tribal nations are weighed by developers and regulators as they determine whether to greenlight a particular project. But the consultation sessions, which are also mandated and carried out by federal agencies, have thus far been designed by state and federal agencies alike to function as little more than a box to be checked, consistently leaving Indian Country open to exploitation.

Section 6 of the Climate Commitment Act was designed to address this shortcoming, as it added the requirement of consent to the consultation process. That is, if a future project brought by the state or private developers encroached on tribal lands in a way that a nation viewed as intrusive or overly cumbersome, the state would recognize the tribe’s ability to decline the project full-stop. This is what is known as Free, Prior, and Informed Consent, a standard set by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007 that is only just now being considered by governments in the United States and Canada. It is what it looks like when settler policy actually respects tribal sovereignty. And this is what Inslee opted to remove from the bill.

Jay Inslee is not an anti-sovereignty climate denier in the mold of Republican counterparts Kristi Noem or Kevin Stitt. Inslee is a lifelong Democrat, atop one of the most progressive state governments in the country, and has established himself as the nation’s loudest and most progressive governor on climate. His short-lived 2020 presidential campaign was kicked off by him declaring the climate crisis “the most daunting challenge” facing the nation. Ten months later, when his candidacy sputtered to an end, he again underscored his commitment to pushing the remaining Democratic candidates to adopt what he viewed as the necessary climate and environmental policy goals. And prior to his veto, Inslee, who is now in his third term as governor, had also built and maintained a fairly strong record of working with the tribal nations his state shares the land with to ensure that, on issues from representation at the state capitol to the fuel tax codes, tribes were adequately represented and heard. But with the stroke of his pen last week, much of that goodwill dissipated.

In a document organized and released by Jaime Martin, the Snoqualmie Tribe’s executive director of governmental affairs, tribal leaders and Democratic state legislators together slammed Inslee for the veto. Fawn Sharp, the president of the National Congress of American Indians and the vice president of the Quinault Indian Nation, described Inslee’s decision as “cowardly,” and an “ambush.” Sharp concluded that “the only thing I will ever agree with Donald Trump about is that Jay Inslee is a snake.” Robert de los Angeles, chairman of the Snoqualmie Indian Tribe, said in a statement that the veto will go down as “a permanent stain on [Inslee’s] record.” Democratic Representative Mike Chapman said he would not have lent his vote to the Climate Commitment Act “without the consultation language that the Tribes negotiated,” and state Senator Kevin Van De Wege acknowledged that “Inslee broke trust with Washington’s Tribes in a away that complicates and damages dialogue with tribes statewide.”

This veto is, admittedly, an abrupt turn from the path the Washington state government had been following in previous years. In 2019, Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson even instituted a policy of tribal consent, requiring his office to seek the approval of tribal nations “before initiating a program or project that directly and tangibly affects tribes, tribal rights, tribal lands and sacred sites.” Ferguson’s policy also updated the attorney general’s litigation process, requiring that the office consult with tribal nations before filing any subsequent legal actions against them. Where Ferguson’s policy applied only to the attorney general’s office, though, the Climate Commitment Act sought to bring the rest of the state government up to speed.

In a statement to the Seattle Times, Inslee’s spokesperson, Mike Faulk, excused the veto by pointing out that the other bills signed by Inslee all contained measures focused on improving tribal-state relations and reminding the Times that tribal consultation policies already exist through the state and federal government. But as Inslee did in his explanation of the veto, Faulk revealed their ultimate gripe with the language in the bill: It was, he said, “written so broadly that it would have made it possible to challenge just about any related project anywhere in the state.”

What Inslee and Faulk highlighted in their critiques of the Climate Commitment Act’s consent section is slightly different from the Biden administration’s ongoing delay in adopting FPIC. Where the White House is weighing its commitment to tribal sovereignty and its desire to appease labor groups (who reportedly oppose FPIC on the grounds that tribal nations will be able to block future job-producing projects), the concerns of the Washington state executive office, by comparison, appear much more petty. It is not an accident that, in Inslee’s official veto explanation, his office went out of its way to underscore that the consent measure “does not properly recognize the mutual, sovereign relationship between tribal governments and the state.” Here, a state government—which is, legally and politically speaking, below the level of tribal nations, who maintain a government-to-government relationship with the federal government—is attempting to overstate its own powers.

Call it a governmental Napoleon complex or, as Sharp did, Inslee being a snake. Either way, what you’re left with is yet another egregious example of how even the most progressive officials, when pressed to relinquish a modicum of their government’s power in the name of righting institutionalized wrongs of colonialism, continue choosing power over Indigenous rights.