Sculpture can tell us a lot about the surface of things. Classical sculpture tells us how a muscle flexes, how a robe folds over a knee, how breasts sit on a body. Modern sculpture can do more: Richard Serra’s massive, tectonic pieces disturb and re-form one’s sense of space and weight (and mortality, if one is up for it). Koons’s stainless steel balloon animals evoke the hidden perversities of the banal. Despite the changes in subject over the centuries, in sculpture we deal mostly with outsides. The earth-shifting quality of Serra comes from the material’s stubborn texture, its impenetrability. The subtle menace of Koons’s work is born of its steely sheen, which works like a grin plastered on a face. In marble sculpture, the precision of the chisel is evinced in a coiled heap of hair that, though frothy, is stonily permanent. Sculpted bodies are hard. Pieces can crack off but not open.

But if the body could crack open, how would sculpture render it? What shapes would this opening take? Eva Hesse and Hannah Wilke—two artists at the center of Erotic Abstraction, a new show at Acquavella Gallery in New York—help to answer this question. On a biographical level, the urge to link the artists makes sense. They were born only four years apart, in 1936 (Hesse) and 1940 (Wilke). They were both Jews and had close ties to tragedy: Hesse arrived in New York in 1939 after fleeing Nazi Germany, her mother committed suicide when Hesse was 10, and she herself died of a brain tumor at 34. Wilke—born in New York—felt surrounded by death in the wake of the Holocaust, her father died suddenly when she was 20, and she died at 52 of cancer. Though there’s no evidence that the artists met, the two painters turned sculptors (turned performance artist–filmmaker, in Wilke’s case) overlapped in New York City’s experimental 1960s art world.

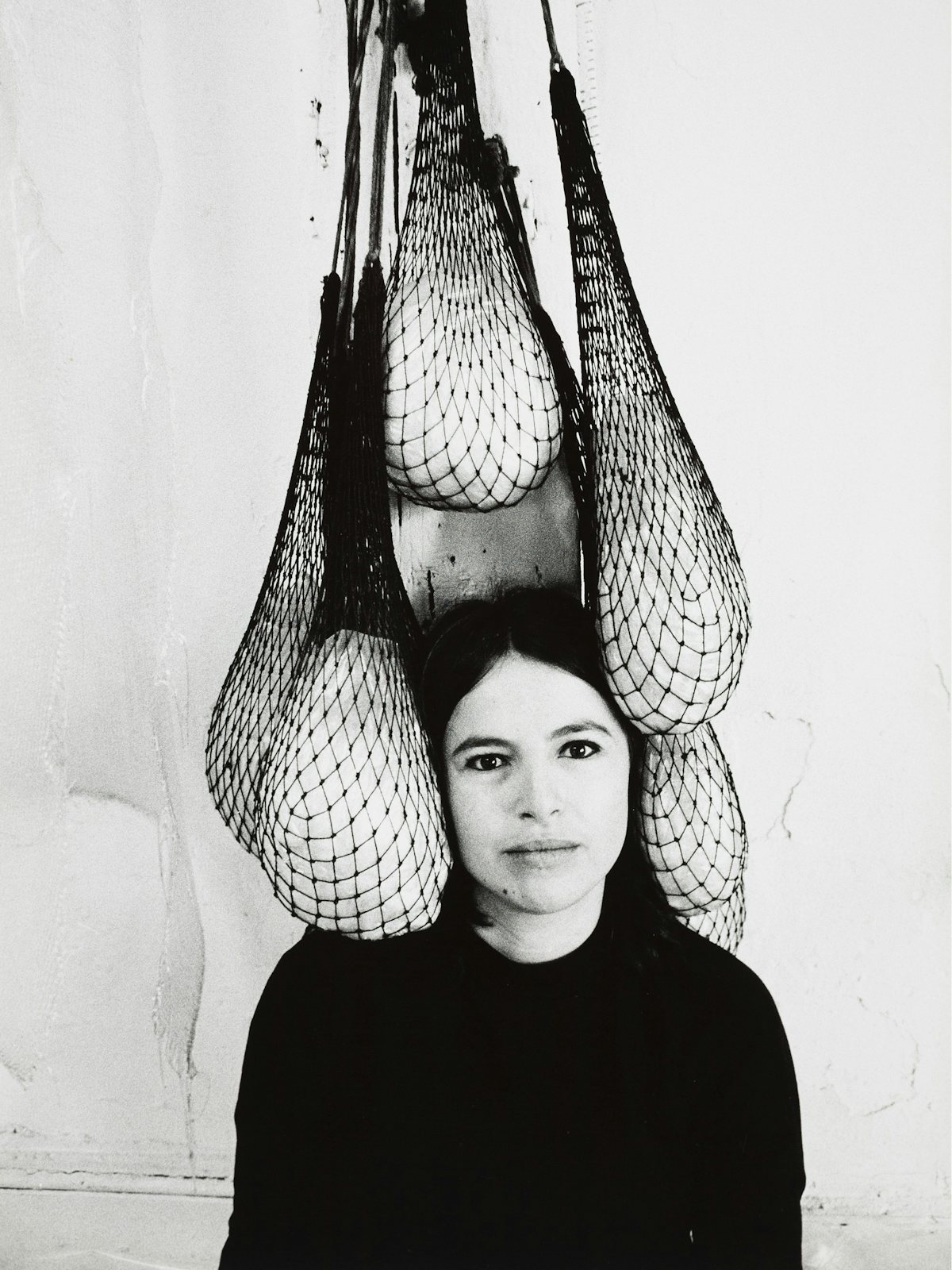

Hesse’s and Wilke’s experiments are captured in real time, in fabulous photos included in the exhibition catalog: Both artists can be found standing or kneeling among liquid latex, fiberglass, and eccentric found objects. In the late ’60s, the appearance of such radical, unwieldy materials was a sure sign that minimalism—the reign of rigid, “inorganic” geometric forms—was ceding to a more “organic” aesthetic. The purities of shape (invigorating or dull, depending on your disposition) were being laid to rest in favor of more “uneven” and conspicuously process-driven art. Where Donald Judd’s boxes might feel shaped and lacquered by platonic form, the work of artists like Hesse and Wilke belonged to the human. Their work is not a formal given but rather the scene of a visible investigation.

A central investigation of Wilke’s: In how many ways can I shape the vulva, with what materials, and to what end? Wilke’s stated concern was to create “a formal imagery that is specifically female.” The gallery puts Hesse’s and Wilke’s work in separate rooms—and in Wilke’s, the labial folds abound. On view are some of her more obvious vulvic forms—what in interviews Wilke variously refers to as her “cunts” and also her “gestural folds”—which are made from glazed ceramic, terracotta, and tightly kneaded erasers (her bubble-gum and dryer-lint forms are not on view). Wilke’s latex-based abstract work, like Ponder-r-rosa 1 (1974), appears like blooming ocean flora pinned to the back wall. Amoebic swaths of latex are bundled together with snaps in The Orange One (1975), which yearns for your touch on the right wall. Indeed, all around the room the body bursts, or flaps, out at you.

But among Wilke’s work there is also a certain quietness. Staring at Untilted (c. 1970s), comprised of over 20 glazed ceramic vulvas that sit close together on a white wooden board, one finds that some of these seashell-esque structures are shier than others. Some show more of their insides (which is really the inside of an inside) so that, when bent down, one can see how in certain forms Wilke’s palm has bent the clay just so, creating concavities only visible upon close viewing. In the intimate room the repeated vaginal viewing disarms the viewer, and also arms the vulva: When, at the far end of the wall, 62 tiny hand-pressed erasers are meticulously glued to a postcard of the Lincoln Memorial, it feels like a vulvic invasion. It made me laugh out loud.

Hesse’s work involves the same investigations of material. It was she, in fact, who pioneered the use of latex in sculpture in 1967. Upon first encountering Hesse’s work, I found it rather elusive and obscure. As if it harbored a secret I was not apt to find out; its special knowledge wasn’t meant for me. Those vertical sheets of cheesecloth, latex, and fiberglass in Contingent—what should I feel toward them? The 19 individual open-lidded cylinders of Repetition Nineteen III, made of fiberglass and polyester resin—what were they telling me?

Then one of her pieces unlocked them all. Hesse’s Accession I (1967) is made of a large open-lidded steel box. Hundreds of tiny holes have been drilled through on each side of the box, and a soft rubber tube has been pushed through each of these holes. The effect is, to use the gallery’s word, erotic. Not in the conventional phallic sense (though there is a hint of unrestrained flaccidity), but in a deeper, carnal sense. In looking at the work, one can’t help but imagine an individual finger pushing the rubber tubes through each of the tiny drilled holes, over and over again. There’s been a repeated squeezing through a tight enclosure, and therein lies a sense of release—like pus pushing through a pore. There’s also the violent urge to stick your hand into the box and feel the rubber tubes press their bulbous tips against your palms. And those tubes, on closer inspection, resemble the fingerlike villi that line the digestive tract. This is fitting, as the piece works not just on you but through you, and a tingling begins as it makes its way.

At the gallery, walking into Hesse’s room, one finds more tinglings among intimate oddities: There are cords hand-dipped in plaster, cloth-covered electrical wires, protuberant half-spheres. More cords (81) dangle mysteriously from a volcanic-looking Masonite board thickened with bits of wood (Iterate, 1966-67). Charging down the wall is a line of interconnected latex boxes—the color and texture of molted skin (an exhibition copy of Sans III, 1969). After 10 minutes in the Hesse room, the linkage between her and Wilke begins to feel frayed. Hesse’s work is galactic. It is more nebulous than Wilke’s and wider in scope, with a sense of cosmic absurdity.

It turns out that the artists’ stated differences of artistic “mission” further belie claims of synchronicity. Of her forms, Wilke has said, “I was aware by the time I was 20 that they were vaginas and we talked about it in college at the time.” Wilke traces her development to the early ’60s, when she “worked in ceramics, creating layered vaginal forms in natural browns and terracotta. [She] added color in around ’63, pink ceramics, and that’s when the vulvic forms evolved.” Hesse, on the other hand, is intentionally evasive when it comes to linking any intelligible image to her work. In her diaries she writes in the spirit of Gertrude Stein or Samuel Beckett:

I would like the work to be non-work. This means it would find its way beyond my preconceptions. What I want of my art I can eventually find. The work must go beyond this. It is my main concern to go beyond what I know and what I can know. The formal principles are understandable and understood. It is the unknown quality from which and where I want to go. As a thing, an object, it acceded to its non-logical self. It is something, it is nothing.

In interviews Hesse refused—politely—to allow her work to be reduced to the erotic, or even to correlate to specific images. In another entry, she writes:

a bag is a bag

a semi-sphere – a semi-sphere

a tube a tube

1 art is what is

2 tension and freedom

3 opposition and contradiction

4 abstract objects

5 not symbols for something else

6 detached but intimate personal

Hesse’s cosmic extratextual art and Wilke’s specific language do not gel, and in a sense it does a disservice to both artists to link them as closely as the curators would like. Wilke’s material seems to have known its destiny before being shaped; whereas in Hesse, the shaping and destiny feel simultaneous, and spontaneous. The consequences of this are eminent in the work. At the very least, however, to see them side by side is to get a full picture of what it meant (and still means) to gleefully evade the canon, and of what it takes to be defiantly unplaceable in the pantheon of art.