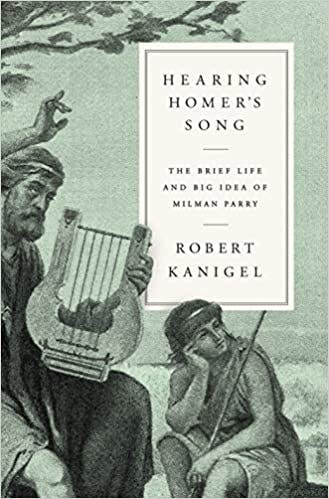

One afternoon in 1935, Milman Parry, a 33-year-old scholar whose research would revolutionize the study of Ancient Greek poetry, was unpacking his suitcase at the Palms hotel in Los Angeles. According to his wife, Marian, Parry was naked from the waist up and rummaging through his clothes when he accidentally jostled a handgun tangled up in a shirt, which sent a bullet into his heart. Underneath a news photograph of Marian taken later that year, a caption read: “Mrs. Milman Parry, who was widowed in Los Angeles, recently, when her husband, in a tragic example of professorial absent-mindedness, accidentally shot himself to death.”

Or at least, as Robert Kanigel writes in his new biography, Hearing Homer’s Song: The Brief Life and Big Idea of Milman Parry, that’s the official version. Whether Milman Parry really died by absentmindedness, suicide, or mariticide—which we will never know, as he was cremated without an autopsy—he was definitely dead, and no longer able to explain himself.

In the story of the tangled-up gun, however, Kanigel gives us Parry’s brief career in miniature: It doesn’t make sense, and yet it happened, and it changed the humanities forever. Parry was a Californian druggist’s son, whose 13 short years in the field undid centuries of prior scholars’ labor, in a flash of inspiration that appears to have first struck him at the tender age of 20, when he was completing his master’s thesis. Barely out of his teens, Parry proposed arguments in that thesis so strong they could have emerged from several lifetimes’ work but seem to have come almost out of nowhere, as Athena sprang fully formed from Zeus’s skull. The thesis barely has any footnotes.

Such a life, such a career, and such a death seem almost beyond explanation. But Kanigel shows that, curiously, Parry’s research tackled a comparable problem. In telling the story of his life—and his atrocious marriage, hitherto not much discussed—Kanigel unites it with Parry’s work to frame a single, massive question: What’s the relationship between tradition and inspiration?

Born middle-class in Oakland in 1902, Milman Parry became famous posthumously for his idea that The Odyssey and The Iliad, thought by many to have been written by an individual human being named “Homer,” were actually the accumulated results of centuries of oral performance by different people.

His argument was that the name we give to that supposed author disguised a bias modern folk have for writing and against listening. In Kanigel’s words, literary critics of the twentieth century associated reading and writing with “advanced civilizations,” and disliked the “repetition and stereotype” that characterizes oral poetry, a leaning that “blinded them to the fecund richness of illiterate cultures.” Although this theory had been modestly proposed by a number of scholars before Parry, and the groundwork was laid by the French scholar Marcel Jousse, who himself grew up amid the oral songsmithery of a largely illiterate community in France, Parry’s innovation lay in the scientific way he proved his inklings.

Using numerical methods, he counted exactly how many times the “ornamental epithets’’ so characteristic of Homeric epics—“γλαυκῶπις Ἀθήνη” (“bright-eyed Athena”), “πολυφλοίσβοιο θαλάσσης” (“loud-roaring sea”), and so on—appeared, and, crucially, where in the dactylic hexameter of the poem’s lines they cropped up. Such epithets were not, Parry showed, functionally descriptive at all; they tended to provide no new information about whatever story was being told but instead existed for what he called the “convenience” of people performing the song. The epithets showed up in “prescribed position and order,” he wrote, essentially filling in metrical gaps wherever they occurred, “giving a permanent, unchanging sense of strength and beauty.”

To prove this further, Parry traveled to the then Yugoslavia, to record the works of the guslars (Balkan singers who sang and played a single-stringed instrument). It was an odd approach to studying Ancient Greek, except when one considers, as Kanigel does, the fact that Milman and Marian had been close with a group of anthropologists, as undergraduates in California, who believed in the comparative method. The guslars showed that Parry was right: Their songs, which were very long, authorless, and dedicated almost exclusively to tales of local heroism and historical grandeur, much like the Homeric epics, would change in quality and in content according to the artist performing them, who, in many cases, made bits up as he went along.

On these trips across what is now Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Albania, Parry took with him a young assistant, Albert Lord, who inherited the project’s vast recording collection when his boss died. This is the reason Parry’s name is probably best known in the formulation “Parry and Lord,” for it was Lord who would alert the world to its bias against the oral in The Singer of Tales, published in 1960. Its most important fan was probably Walter Ong, whose 1982 book Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word influenced thinkers far outside the world of classics.

What came to be known as the “oral-formulaic theory” spread across disciplines, and Lord himself learned Old and Middle English in order to apply the ideas to the epics of northern Europe, like Beowulf. Even better, Kanigel follows the tendrils of Parry’s stories into yet more surprising places. Albert Lord met the Albanian writer Ismail Kadare at a 1979 conference in Ankara, Turkey, it turns out. After hearing his “tale” about Parry’s travels, Kadare wrote a novel about it, published in 1988 as Le Dossier H.—“H” for Homer.

Kanigel looks for clues in an unplumbed region of Parry’s life: his unhappy marriage to Marian, whose own undergraduate degree was cut short by her unexpected pregnancy with their first child. Parry was a social conservative who expected Marian to keep house and tend their offspring. He dragged her across Europe, leaving her indoors while he went adventuring. Kanigel quotes Harry Levin, a student of Parry’s, who recalled his unkind treatment of Marian alongside other forms of his social conservatism: In Yugoslavia, Levin said, Parry “respected the hierarchical nicety with which his hosts handed out the different cuts of meat,” since such an approach to society “seemed invested with an order” that modern life lacked.

It appears odd at first that a man so radical in his academic work would be staunchly retro in his personal politics. But it’s less surprising when we consider his particular attitude toward the “traditional” in poetry.

The word “tradition” has over time become irrevocably intertwined with social politics, evidenced by the way Kanigel describes Parry’s views on women as “traditional.” But there is nothing at all inherently politically conservative about tradition, in Parry’s formulation. He wrote his doctorate in 1920s Paris, surrounded by Modernist writers and artists who were defining their work as nontraditional even as they sought to use modern techniques to reimagine classic texts (think of Joyce’s Leopold Bloom representing a twentieth-century Odysseus), giving rise to a newly conservative definition of “tradition” by dint of contrast. Parry was personally a fan of Apollinaire, Eliot, and Cummings, his student Levin recalls, but in the manner of a pleasure kept strictly separate from the workday.

The etymology of the word contains the keys to Parry’s enthusiasm. Tradition is, like the word extradition, based on the idea of things being handed over, from the Latin tradere. So “traditional” poetry was for Parry not about stasis but about the dynamic handing-down of the most valuable in a culture over vast stretches of time, preserving the best of it while subjecting the rest to change. It was not a stifling bind but the very medium of certain kinds of poetry. The Homeric epic, he wrote, was “the highest possible development of the hexameter medium to tell a race’s heroic tales.”

Parry posited the oral-formulaic technique as the acme of nonmodern creativity, and as a result he emphasized the collective authorship of a people over the individual inspiration of a person—hence his odd invocation of “race” in a discussion about poetry. His theories could not but valorize the collectivity and insularity of such peoples, which ultimately led him to respect their values—however retrograde, hierarchical, or obsessed with violent “heroism”—almost indiscriminately.

Whether Modernist or “traditional,” many thinkers of the interwar period were obsessed by the role of history and the passing of time in art. They simply came up with different interpretations of what to do about it, with some breaking away from the past and others diving into it. We live today with the fruits of those writers’ labors, for they defined for us notions about what poetry is and is not, and has or has not been. Kanigel’s biography shows that those definitions have led historical lives of their own, through a portrait of a man who best embodied Hippocrates’ old axiom: “Ὁ βίος βραχύς, / ἡ δὲ τέχνη μακρή,” (“Life is short, and art long”).