When I was an undergraduate, long ago, there was a legend at my college concerning a student who was up for a summa cum laude degree in English literature and failed not only to garner that high honor but to receive an honors degree at all. According to the legend, this happened because, during his oral exams, he confessed that he had never read the multivolume novel Middlemarch by British author George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans). The legend was assumed to be apocryphal, but also to indicate the English department’s conviction that if you had not read this work, then ipso facto you had not mastered this chosen field of study.

What was it about Middlemarch that made it so important? Its complete title is Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life, and it is described in its Wikipedia entry as following “distinct, intersecting stories with many characters.” In fact, the book has more than two dozen distinct and important characters. Henry James wrote of them, “All these people, solid and vivid in their varying degrees, are members of a deeply human little world, the full reflection of whose antique image is the great merit of these volumes.” Eliot depicted, in all its fullness and complexity, an entire provincial social order, discernible as such.

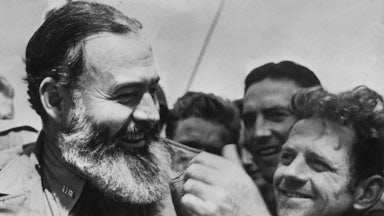

I thought of George Eliot and Middlemarch recently while watching the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) series about the twentieth-century American writer Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway, in contrast to Eliot, never wrote much about the social milieu with which he was most familiar, his hometown of Oak Park, Illinois, and the neighboring city of Chicago, though he surely must have considered doing so. The PBS documentary, and my own readings, suggested why he could never have successfully completed such a project.

In any Hemingway short story or novel, whether it is filtered through a first- or third-person narrator, there is really only one perspective presented, one voice: that of the author. Whether it is Nick Adams, or Jake Barnes, or Lieutenant Henry, or an elderly Cuban fisherman, it is the perceptions of Hemingway himself that you are given, and his voice—his singular, inimitable, incantatory voice—that you hear. There is nothing wrong with this, and in fact, given the goal Hemingway set for himself when he began writing in earnest in Paris in the 1920s—to learn to describe not the emotion a character experienced, but the thing or phenomenon that produced the emotion, which in turn would evoke a similar reaction in the reader—it could hardly have been otherwise. Such a methodology can only be brought to bear through the consciousness of a single individual.

The Hemingway protagonist is typically alone. Nick Adams, the sole character of “Big Two-Hearted River,” fishes all by himself throughout one of the longest short stories the author ever wrote. Jake Barnes, the shattered World War I veteran and narrator of The Sun Also Rises, has surrounded himself with a group of carousing expatriates, but the reader senses a hollow loneliness beneath the glittering life of Paris. This foreshadows a pattern in Hemingway’s real life, in which he was adept at assembling groups of transitory comrades, but a failure at fostering and preserving deeper human ties. At the end of A Farewell to Arms, Lieutenant Henry, leaving his love on the slab where she has just died in childbirth, walks back to the hotel, alone, through the rain. In the finale of For Whom the Bell Tolls, Robert Jordan, an American volunteer serving the Loyalist cause in Spain, lies alone on the ground, his gun poised, awaiting certain death at the hands of an approaching column of Fascist troops. The elderly fisherman Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea, who has finally caught a giant marlin after 84 straight days of failure but then lost it to sharks, might have pulled it to shore unscathed if accompanied by the young assistant who had left for a new crew after his family lost patience with Santiago’s bad luck.

What about politics? Hemingway once remarked that the best use for the pages of The New Republic was as toilet paper. Though he covered various political events as a young journalist in Europe, political issues per se are absent from his fiction up to the mid-1930s. This attitude contrasts with the keen interest in political affairs, focused on the Reform Act 1832 (which expanded the franchise in Britain), shown by various characters in Middlemarch, reflective of that author’s social concerns. Taken to task by leftist writers for his apparent indifference to the plight of the proletariat in the Depression, Hemingway wrote to a friend, “I cannot be a communist now because I believe in only one thing: liberty.” However, the onset of the Civil War in 1936 in Spain, a country dear to his heart, drew his attention. He went to Spain as a war correspondent, advocating for the Republican cause while refusing to expose the atrocities committed against noncommunist Loyalists by thugs subservient to Joseph Stalin. Asked if he was now a communist, Hemingway’s Robert Jordan famously retorted that he was, rather, an anti-fascist.

The remainder of Hemingway’s life is a sad tale of increasing physical and mental deterioration, escalating alcoholism and marital discord, and unbearable frustration at his inability to write like the Hemingway of old, now only a legend. He did, however, eke out one final, unique masterpiece, The Old Man and the Sea, which helped win him a Nobel Prize, and which William Faulkner speculated might be considered the greatest American literary achievement of their generation. Faulkner, attuned, like George Eliot, to the complexity of human life, had said that “man will not merely endure: he will prevail.” Hemingway, portraying a fisherman alone at sea against the elements, proclaimed: “Man is not made for defeat.... A man can be destroyed but not defeated.”