Ernest Hemingway had the chance to become the spokesman of the war generation, or, more particularly, he came to be regarded as the spokesman of that generation by those who had not, in their own persons, known the experience of war. The phrase which he had culled from one of his many conversations with Gertrude Stein and printed opposite the title page of The Sun Also Rises—“You are all a lost generation”—was destined to faire fortune. And to this he appended another quotation from the aged and charming cynic of Ecclesiastes, which not only pointed the title of his book, but linked its own disillusionment with another so old and remote in time as to seem a permanent proclamation of the vanity of things.

His own generation admired him, but could also appraise how special his experience had been. It was still a younger generation, those who were school-boys at the time of the War; who were infatuated with him. Hemingway not only supplied them with the adventures they had missed; he offered them an attitude with which to meet the disorders of the postwar decade. It was they who accepted the Hemingway legend and by their acceptance gave it a reality it had not had.

It is as one who dictated the emotions to contemporary youth that Hemingway has been compared to Lord Byron. The comparison is in many ways an apt one. The years of Byron’s fame were not unlike the decade after the last war. The hopes raised by the French Revolution had then been frustrated and all possibilities of action were being rapidly destroyed by those in power. In the 1920’s, the disintegration of the social fabric which began before the War became apparent to almost anyone. Here and there were new faces in politics, but Hemingway, who had worked on a Midwestern paper in his youth, gone abroad shortly after the War as correspondent to a Canadian newspaper, come into contact with the literary diplomats at the Quai d’Orsay, followed the French troops of M. Poincare into the Ruhr, known Mussolini when he too was a journalist, seen war and government from both sides in the Turkish-Greek conflict, was not likely to rate the new gangsters above the old gangs. It should have been obvious to a disinterested observer in 1922 that there was no longer much prospect of immediate revolution in the countries of Europe. It was in 1922 that Hemingway seriously began his career as a writer.

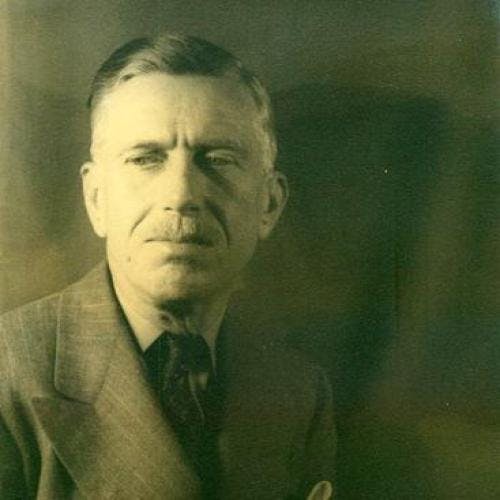

He was to become, like Byron, a legend while he was in his twenties. But when I first met him in the summer of 1922 there could be no possibility of a legend. I had just come abroad and calling on Ezra Pound had asked him about American writers of talent then in Paris. Pound’s answer was a taxi, which carried us with decrepit rapidity across the Left Bank, through the steep streets rising toward Mont, Saint Genevieve, and brought us to the Rue du Cardinal Lemoine. There we climbed four flights of stairs to find Ernest Hemingway. He had then published nothing except his newspaper work, none of which I have ever seen; so that my impressions could be only personal. From that time until 1930 I saw Hemingway fairly constantly. Since then he has retired to Florida, and I have seen him but once. Any later impressions I have are gathered entirely from his books.

Hemingway, as he then appeared to me, had many of the faults of the artist, some, such as vanity, to an exaggerated degree. But these are faults which from long custom I easily tolerate. And in his case they were compensated for by extraordinary literary virtues. He was instinctively intelligent, disinterested, and not given to talking nonsense. Toward his craft he was humble, and had, moreover, the most completely literary integrity it has ever been my lot to encounter. I say the most complete, for while I have known others who were not to be corrupted, none of them was presented with the opportunities for corruption that assailed Hemingway. His was that innate and genial honesty which is the very chastity of talent; he knew that to be preserved it must constantly be protected. He could not be bought. I happened to be with him on the day he turned down an offer from one of Mr. Hearst’s editors, which, had he accepted it, would have supported him handsomely for years. He was at the time living back of the Montparnasse cemetery, over the studio of a friend, in a room small and bare except for a bed and table, and buying his midday meal for five sous from street vendors of fried potatoes.

In attempting to say what has happened to Hemingway, I might suggest that, for one thing, he has become the legendary Hemingway. He appears to have turned into a composite of all those photographs he has been sending out for years: sunburned from snows, on skis; in fishing get-up, burned dark from the hot Caribbean; the handsome, stalwart hunter crouched smiling over the carcass of some dead beast. Such a man could have written most of Green Hills of Africa.

Byron’s legend is sinister and romantic, Hemingway’s manly and low-brow. One thing is certain. That last book is hard-boiled. If that word is to mean anything, it must mean indifference to suffering and, since we are what we are, can but signify a callousness to others’ pain. When I say that the young Hemingway was among the tenderest of mortals, I do not speak out of private knowledge, but from the evidence of his writings. He could be, as any artist must in this world, if he is to get his work done, ruthless. He wrote courageously, but out of pity; having been hurt, and badly hurt, he could understand the pain of others. His heart was worn, as was the fashion of the times, up his sleeve and not on it. It was always there and his best tricks were won with it. Now, according to the little preface to Green Hills of Africa, he seems to think that having discarded that half-concealed card, he plays more honestly. He does not. For with the heart the innate honesty of the artist is gone. And he loses the game.

The problem of style is always a primary one, for to each generation it is presented anew. It is desirable, certainly that literature reflect the common speech; it is even more necessary that it set forth a changed sensibility, since that is the only living change from one generation to another. But to an American who, like Hemingway, was learning the craft of prose in the years that followed the War, that problem was present in a somewhat special way. He must achieve a style that could record an American experience, and neither falsify the world without nor betray the world within.

How difficult that might be, he could see from his immediate predecessors; they had not much else to teach. On the one side there was Mr. Hergesheimer, whose style falsified every fact he touched. On the other was Mr. Dreiser, a worthy, lumbering workman who could deliver the facts of American existence, all of them, without selection, as a drayman might deliver trunks. Where, then, to start? To anyone who felt there was an American tradition to be carried on, there was but one writer who was on the right track: Sherwood Anderson. When he was in his stride, there was no doubt about it, he was good. The trouble with Anderson was there was never any telling just how long he could keep up his pace. He had a bad way of stumbling. And when he stumbled he fell flat.

So did Mark Twain, who loomed out of the American past. All authentic American writing, Hemingway has said, stems from one book: Huckleberry Finn. How much he was prepared to learn from it may be ascertained by comparing the progress of the boys’ raft down the Mississippi with the journey of Jake and his friend from France to Spain in The Sun Also Rises. Mark Twain is the one literary ancestor whom Hemingway has openly acknowledged; but what neither he, nor Sherwood Anderson, who was Hemingway’s first master, could supply was a training in discipline.

It was here that chance served. But it was a chance from which Hemingway carefully profited. There was one school which for discipline surpassed all others: that of Flaubert. It still had many living proponents, but none more passionate than Ezra Pound. In Paris, Hemingway submitted much of his apprentice work in fiction to Pound. It came back to him blue-penciled, most of the adjectives gone. The comments were unsparing. Writing for a newspaper was not at all the same as writing for a poet.

Pound was not the young American’s only critical instructor. If Hemingway went often to 70 bis, Rue Nôtre Dame des Champs, he was presently to be found also at 12, Rue de Fleurus. There he submitted his writings to the formidable scrutiny of Gertrude Stein. It was of this period that Hemingway said to me later: “Ezra was right half the time, and when he was wrong, he was so wrong you were never in any doubt about it. Gertrude was always right.”

What she taught Hemingway must be in part left to conjecture. Like Pound, she undoubtedly did much for him simply by telling him what he must not do, for a young writer perhaps the most valuable aid he can receive. More positively, it was from her prose he learned to employ the repetitions of American speech without monotony. (I say this quite aware that Miss Stein’s repetitions are monotonous in the extreme.) She also taught him how to adapt its sentence structure, inciting in him a desire to do what Hemingway calls “loosening up the language.” She did not teach him dialogue. The Hemingway dialogue is pure invention.

In The Sun Also Rises, each of the characters has his own particular speech, but by the time we reach Death in the Afternoon and the extraordinary conversations with the Old Lady, there is no longer even the illusion that there is more than one way of talking. It is a formula, in that book employed with great dexterity and no small power; but it is dramatic only in words; in terms of character it is not dramatic at all.

We were in the garden at Mons. Young Buckley came in with his patrol from across the river. The first German I saw climbed up over the garden wall. We waited until he got one leg over and then potted him. He had so much equipment on and looked awfully surprised and fell down in the garden. Then three more came over further down the wall. We shot them. They all came just like that.

It is easy to see how a story like this could convey the impression that Hemingway is indifferent alike to cruelty and suffering. And yet this tale is a precise record of emotion. What we have here is not callousness, but the Flaubertian discipline carried to a point Flaubert never knew—just as in the late war military control was brought to such perfection that dumb cowed civilians in uniform, who cared nothing for fighting and little for the issues of battle, could be held to positions that the professional soldiers of the nineteenth century would have abandoned without the slightest shame. In this account of the Germans coming over the wall and being shot, one by one, all emotion is kept out, unless it is the completely inadequate surprise of the victims. The men who kill feel nothing.

But this was a point beyond which Hemingway himself could not go. And in the stories that follow the first little volume, published in Paris and called In Our Time, he is almost always present in one guise or another. That is not to say, as might be assumed, that these stories are necessarily autobiographical. Wounded in the War, Hemingway was a very apprehensive young man. Indeed, his imagination could hardly be said to exist apart from his apprehension. I should not call this fear. And yet he could hardly hear of something untoward happening to another that he did not instantly, and without thought, attach this event to himself, or to the woman he loved. The narration is still remarkably pure. But there is always someone subject to the action.

For this is another distinction. In Flaubert, people are always planning things that somehow fail to come off—love affairs, assignations, revolutions, schemes for universal knowledge. But in Hemingway, men and women do not plan; it is to them that things happen. In the telling phrase of Wyndham Lewis, the “I” in Hemingway’s stories is “the man that things are done to.” Flaubert already represents a deterioration of the romantic will, in which both Stendhal and Byron, with the prodigious example of Napoleon before them, could not but believe. Waterloo might come, but before the last battle there was still time for a vast, however destructive, accomplishment of the will. In Hemingway, the will is lost to action. There are actions, no lack of them, but, as when the American lieutenant shoots the sergeant in A Farewell to Arms, they have only the significance of chance. Their violence does not make up for their futility. They may be, as this casual murder is, shocking; they’re not incredible; but they are quite without meaning. There is no destiny but death.

It is because they have no will and not because they are without intelligence that the men and women in Hemingway are devoid of spiritual being. Their world is one in time with the War and the following confusion, and is a world without traditional values.

It is the privilege of literature to propose its own formal solutions for problems which in life have none. In many of the early stories of Hemingway the dramatic choice is between death and a primitive sense of male honor. The nineteen-year-old Italian orderly in A Simple Enquiry is given to choose between acceding to his Major’s corrupt desires and being sent back to his platoon. Dishonor provides no escape, for in The Killers the old heavyweight prizefighter who has taken that course must at last lie in his room, trying to find the courage to go out and take what is coming to him from the two men who are also waiting in tight black overcoats, wearing gloves that leave no fingerprints. One can make a good end, or a bad end, and there are many deaths beside the final one. In Hills Like White Elephants, love is dead no matter what the lovers decided. “I don’t feel any way,” the girl says. “I just know things.” And what she knows is her own predicament.

The Spaniards stand apart, and particularly the bullfighters, not so much because they risk their lives in a spectacular way, with beauty and skill and discipline, but because as members of a race still largely, though unconsciously, savage, they retain the tragic sense of life. In The Sun Also Rises, the young Romero, courteous, courageous, born knowing all the things that the others—wise-cracking Americans, upper-class British or intellectual Jews—will never learn, is a concentration of contrast. And yet the character in that novel who most nearly represents the author is aware, as soon as he has crossed the border back into France, that it is here that he belongs, in the contemporary world. He is comfortable only where all things have a value that can be expressed and paid for in paper money.

The best one can do is to desert the scene, as every man and woman must do sooner or later, to make, while the light is still in the eyes, a separate peace. And is this not just what Hemingway has done? Is there a further point to which he can retire than Key West? There he is still in political America, but on its uttermost island, no longer attached to his native continent.

His vision of life is one of perpetual annihilation. Since the will can do nothing against circumstance, choice is precluded; those things are good which the senses report good; and beyond their brief record there is only the remorseless devaluation of nature, which, like the vast blue flowing of the Gulf Stream beyond Havana, bears away of our great hopes, emotions and ambitions only a few and soon disintegrating trifles. Eternity—horribly to paraphrase Blake—is in love with the garbage of time.

What is there left? Of all man’s activities, the work of art lasts longest. And in this morality there is little to be discerned beyond the discipline of the craft. This is what the French call the sense of the métier and their conduct in peace and war has shown that it may be a powerful impulse to the right action; If I am not mistaken, it is the main prop of French society. In The Undefeated, the old bullfighter, corrupt though he is with age, makes a good and courageous end, and yet it is not so much courage that carries him as a proud professional skill. It is this discipline, which Flaubert acquired from the traditions of his people and which Pound transmitted to the young Hemingway, that now, as he approaches forty, alone sustains him.