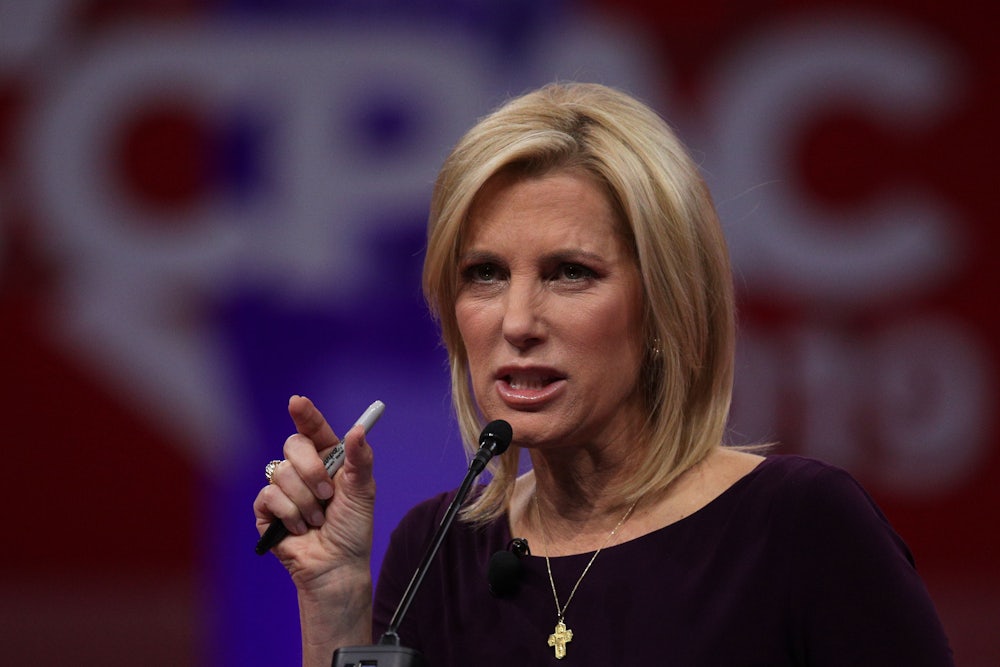

Laura Ingraham’s monologue on Thursday evening was all about canceling the myriad corporations—including Delta and Coca Cola—who have come out against the restrictive new voting bill signed into law in Georgia last week. “It’s time to teach corporate America that if they attack Georgia or any state like it for doing what they did to secure their right to vote, these corporations are going to face the wrath of GOP officials as well as the tens of millions of American consumers who support them,” Ingraham said, perhaps thinking of the groups who have successfully convinced companies to stop advertising on Fox News. “That means lobbyists and CEOs, they need to be told in no uncertain terms if you try to help the left rig elections, we’re going to punish you.”

The editors of National Review came to a similar conclusion earlier the same day, arguing that Georgia Republicans should stand up to “the capture of America’s major corporations by the social-justice-warrior wing of the Democratic Party,” claiming that the titans of industry running these companies were actually being held hostage by the woke mob. Perhaps most brazenly, they argued that corporations threatening to pull out of a state passing laws aimed at disenfranchising voters was an affront to “the democratic right of a free people to pass laws through their elected representatives, chosen in free and fair elections.”

The fierce criticism the bill has received—and, particularly, its emergence as a wedge between the GOP and its corporate base—has put the Republican Party and its backers in the media on the defensive. But the contortions being offered to make this bill seem benign are in themselves damning. No one in conservative media can actually justify the bill’s existence because it is unjustifiable in and of itself: Aimed at eliminating nonexistent fraud, the bill’s actual purpose is to make it harder for Democrats to win elections.

The defenders of Georgia’s bill are particularly offended by critics’ invocation of Jim Crow. Writing in The Washington Post, Henry Olsen referred to these critiques as a “calumny” that “besmirches an effort that largely succeeds at balancing extensive voter access with strong election integrity.” National Review’s Rich Lowry, meanwhile, writes that “the old Jim Crow was billy clubs and fire hoses; the alleged new Jim Crow is asking people to write a driver’s license number on their absentee-ballot envelopes.”

This type of operatic outrage at allegations of racism has been a calling card of the right for decades. (They are particularly rich coming from anyone working at National Review, which literally defended segregation.) In this instance, these writers ignore the actual substance of the criticisms. The point of the comparisons to Jim Crow is that Republicans in states across the country are working to limit access to voting in ways that will disproportionately affect minority voters. These new restrictions are more subtle than the crude racism of Jim Crow, but that’s the entire point of these laws: to discriminate without having nakedly racist language on the books. As a Washington Post analysis concluded, we are witnessing “the most sweeping contraction of ballot access in the United States since the end of Reconstruction, when Southern states curtailed the voting rights of formerly enslaved Black men.”

The New York Times, meanwhile, has identified 16 provisions in the bill that make it harder for many Georgians to vote. Joe Biden won the state by a 2-1 margin among absentee voters; the law restricts and curtails vote-by-mail and other forms of early voting. Absentee ballots have “strict ID requirements” that could result in many being thrown out; ID requirements themselves have been found to depress turnout among minority voters in particular. At the same time, the law also criminalizes anyone providing food and water to voters standing in lines to vote who isn’t a poll worker. Long lines have been shown to discourage people from voting, and Georgia has had very, very long lines in recent years. Defenders of the law have noted, as Lowry does, that “Poll workers can provide food and drink for general use.”

There are two issues here. One is that policies that encourage long lines are a voter suppression tactic in and of themselves; by making it harder (and, in Georgia’s case, literally criminalizing) to give food and water to people waiting in line, the Georgia law is making it harder to vote. At the same time, it’s not clear what problem this is actually trying to solve. Theoretically, it prevents “electioneering” by non-poll workers—in this formulation, offering food and drink to someone is akin to fraud. But the defenders of the law have not been able to identify any examples of people bribing those waiting in line with food and drink or, more strangely, of someone waiting in line for hours and then voting for a specific candidate because they were given food and drink by someone.

National Review’s Charles Cooke, blaming Stacey Abrams for the whole thing, went as far as to suggest that the response to changes to Georgia’s voting laws was equivalent to Trump’s efforts to overturn the state’s result. “One cannot help but feel sorry for Secretary of State Raffensperger and his chief operating officer, Gabriel Sterling, who have now been required twice within the last six months to face down an angry, tempestuous mob while armed with nothing more potent than the uninspiring truth,” he wrote. The “uninspiring truth” here is that this law isn’t intended to suppress votes, when a great deal of evidence suggests that is exactly what it is meant to do. Lowry, at least, is upfront about the assumption he’s laboring under. “The deeper point is that in the contemporary United States, with such wide and ready access to the ballot, changes around the edges don’t disenfranchise people,” he writes. Voter suppression, in other words, is a fantasy. (It’s not.)

One big question is missing from all of these defenses, however: What is the actual problem this law is solving? Olsen alludes to it when he suggests that the law “balances” concerns about access with those of integrity. But this law only exists because of the baseless charges of fraud made by Donald Trump and his allies after his 2020 loss. There have been no instances of actual fraud and no reason to introduce sweeping new measures aimed at “balancing” voting access with anything. There is no reason to believe it would exist had he legitimately won the election.

Although these writers are shocked—shocked!—that Democrats are rallying their base against these efforts, Republicans have a very clear political motivation for pushing through these laws. They have spent months convincing their voters that the election was “stolen,” that Donald Trump is the rightful president, and as Ingraham argued, that the left is determined to continue rigging elections unless they are stopped. But this is, in itself, a political problem for Republicans—what exactly are they doing to break the hold that Antifa, George Soros, and Joe Biden have over our elections? And, similarly, why should their voters turn out at all if a shadowy cabal of CEOs, voting technology companies, and Democrats are just going to alter the results anyways? Now they need to convince them that they’ve fixed the problems, so they’ll continue going to the polls. In Georgia, Republicans have found a path forward: Fix a nonexistent problem while creating a host of new ones.