Writing in The Washington Post shortly after the January 6 Capitol insurrection, Margaret Sullivan noted a sea change in American journalism. After months of Republican lies about voter fraud and an attempt to disrupt the presidential transition, “the gloves have come off,” she wrote. “The language that journalists feel free to use is far more direct, far less mired in cautious respect for the highest office in the land.”

Even the reporters most wedded to access, and to the conventions of “both sides” journalism, were clearly describing what was happening in front of their noses. Reality was not determined by partisanship, situated somewhere between a comment from a Democrat and one from a Republican. The moment demanded journalism that was clearer and less “neutral.” American democracy itself was under threat.

There was a sense that the conventions that had defined political journalism for decades may have been shifting under the weight of the unfolding crisis. How can you practice both-sides journalism when one of the sides had turned its back on democracy? Media outlets became explicit: Any claim of fraud or a “stolen” election was not only a lie, but a big lie.

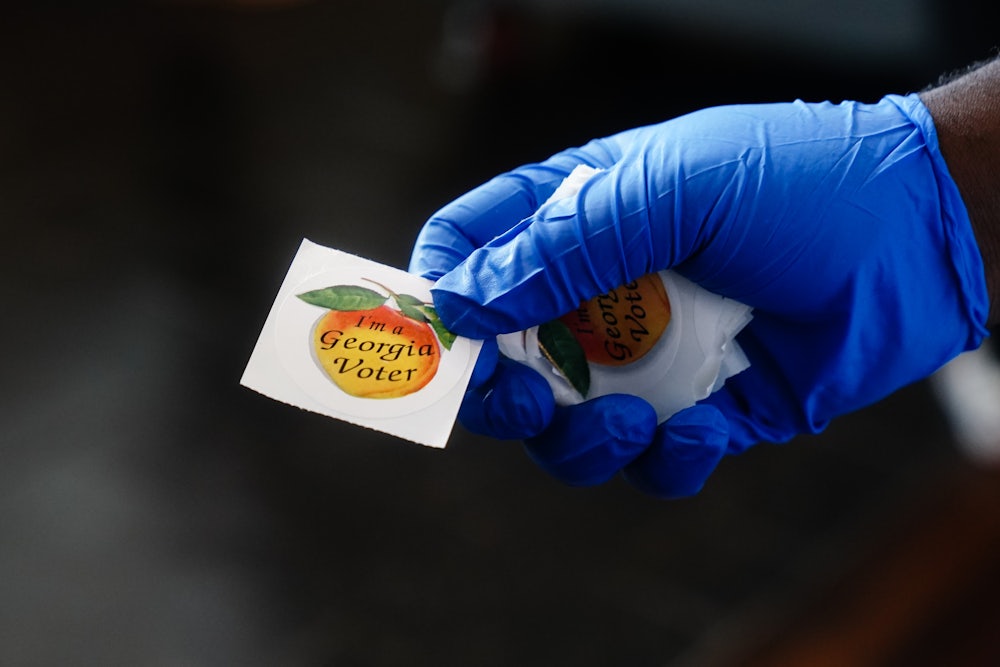

But a strange thing has happened over the last few months. Across the country, the Republican Party began proposing, then passing, sweeping new laws to restrict voting access—over 250 such proposals in 43 states, according to a Brennan Center study released two weeks ago. Last week, Republicans in Georgia, which just elected two Democrats to the U.S. Senate for the first time in decades, passed a bill that will add ID requirements to voting, decrease access to ballot drop boxes, and even block non-poll workers from providing food and drink to people waiting in line to vote.

The law also removes the secretary of state, who had resisted Trump’s efforts to overturn Georgia’s election results, from the Board of Elections, replacing him with a figure who answers to the legislature. If such a figure had been in place in the 2020 election, it is possible that Georgia’s electoral votes would have been baselessly handed to Trump last year.

The GOP is, in other words, laying the groundwork to steal elections, both by limiting access to poor and non-white voters and by making it easier to overturn unfavorable results. This is all happening as a direct result of Trump’s lies about a “stolen election,” which have, ironically, created the pretext for Republicans to do exactly that in states across the country. But despite this connection, the press is reverting to its old, bad ways, treating an existential threat to democracy as a mere partisan conflict.

On Meet the Press, Republican Pat Toomey made the case that “there is a completely false narrative about so-called voter suppression” coming from the left. “You look at the Georgia law, there’s no voter suppression,” he said, adding that the new policy has “nothing to do with race.” These are statements you hear a lot in defense of the Georgia bill, but moderator Chuck Todd didn’t push Toomey on them. Instead he wondered if the changes were a “good look,” given Trump’s loss in the presidential election—oh no, Republicans are acting like sore losers!

Politico Playbook noted the passage of the restrictive new measures by writing, “Your move, Democrats.” The Republicans have made their move (sweeping changes to voting laws based on lies); now it’s time for Democrats to make a partisan gambit in response, which is invariably painted as being equivalent to the GOP’s authoritarian maneuvers. National Journal’s Josh Kraushaar, meanwhile, noted the silver lining for Democrats, which is that the “overheated” allegations of suppression would help turn out their base, even though the whole point of this wave of laws is to restrict Democrats from doing exactly that.

There is an assumption that Republican efforts to subvert democracy are roughly akin to the Democratic Party’s interest in getting rid of the filibuster, which it would then use to pass sweeping voting rights legislation. The idea is that although Republicans are currently making it harder for Democrats to vote (which is good for Republicans) Democrats may respond by making it easier for everyone to vote (which is good for Democrats). In the jaundiced calculus of Beltway reporting, these things are similar—nothing more than electoral ploys to alter the parties’ prospects. (It is, per Kraushaar’s point, rarely considered that these bills could also be about juicing Republican turnout—having convinced their voters that elections are regularly stolen, the GOP now must convince them that the fraud issue has been fixed, or risk their voters ceasing to turn out altogether.)

Many in the press remain curiously averse to ascribing intent, even when it’s obvious. The goal of these bills couldn’t be clearer—Republicans want to make it easier for them to win elections and easier to overturn them when they don’t. We know this because Republicans have spent the last several months making false claims that the 2020 election was “stolen” from Donald Trump and because his campaign, working in concert with state legislatures in battleground states, tried to overturn it. These events culminated in a literal insurrection that left five people dead. Having failed to succeed in overturning an election in 2020, they are changing the rules to make it easier.

There should be nothing partisan about strengthening democratic safeguards, especially after what happened at the Capitol on January 6. For a brief moment, the Beltway press understood that. Let’s hope it’s not too late when they remember it again.