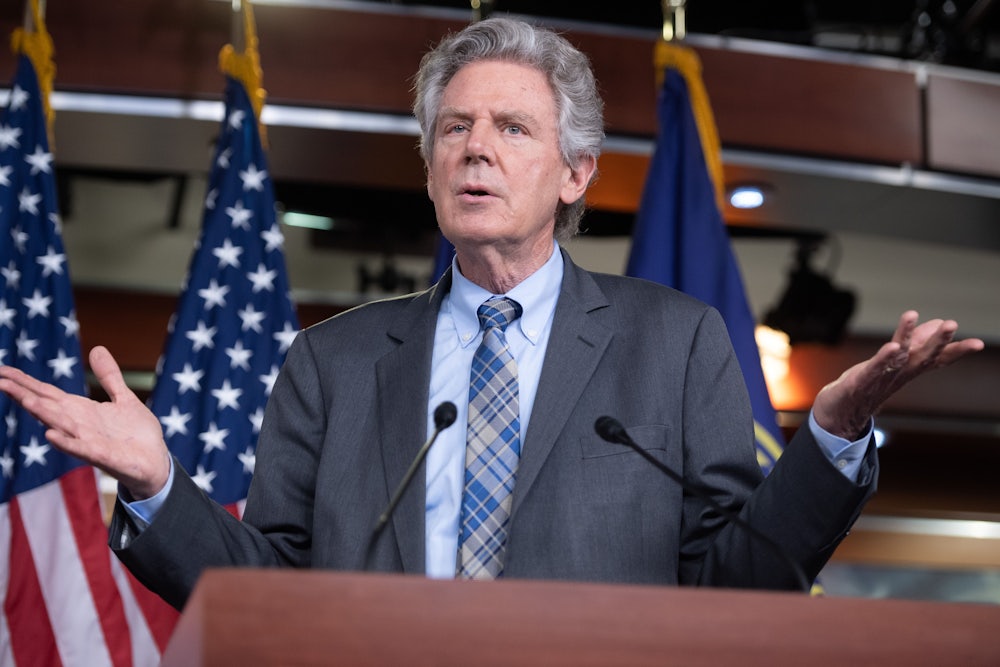

In a sleepy virtual hearing on Monday, New Jersey Democrat Frank Pallone—chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee—introduced former Energy Secretary Ernie Moniz as the first witness to talk about his sprawling infrastructure proposal, the LIFT America Act. As Moniz declared in a standard disclosure prior to the hearing, he also serves on the board of Southern Company, a vertically integrated for-profit electric utility. Pallone, in turn, has gotten $12,500 worth of campaign contributions from Southern Company in the last three election cycles, and $343,318 in total from electric utility PACs over the same time period, per the Center for Responsive Politics.

While the $12,500 from Southern is chump change by current Beltway standards, all told, Pallone took in the fifth-largest haul of corporate PAC money of any House candidate last cycle, as Sludge reported last week. Pallone, who since becoming chair of the committee in 2018 has been the filter through which legislation on everything from agriculture to health care to climate change flows, has received rapidly increasing contributions from the energy industry in particular. Since becoming the ranking Democrat on the Committee in 2014, he’s gotten a total of $594,926 from energy and natural resource company PACs, including $298,000 just this past cycle. That’s up from the $173,619 he got from the same groups in the 2018 cycle, $92,219 in 2016, and $31,088 in 2014. Top donors have included PSE&G, NRG, and FirstEnergy, the utility at the center of a massive corruption investigation in Ohio. His campaign contributions from oil and gas companies—while modest compared to electric utility company contributions—have doubled over the last two cycles, from $21,000 to $45,500.

So what are Pallone’s corporate donors getting in return?

As a rule, spending by fossil fuels interests is highly partisan, with Republicans raking in far more of it than Democrats. And committee chairs and ranking members getting an influx of cash from relevant industries isn’t exactly novel. In the Senate, for instance, Joe Manchin—who heads the Energy and Natural Resources Committee—accepted $339,000 from energy and natural resource PACs this past cycle alone, including $136,000 from oil and gas PACs and $137,000 from electric utilities. Over the same period, ranking Republican John Barrasso, of Wyoming, got $705,650 from energy and natural resource PACs, with $347,000 of that coming from oil and gas PACs and $221,250 from electric utilities.

Unlike either Manchin or Barrasso, Pallone has a broadly liberal voting record and isn’t among the body’s most conservative Democrats, boasting a 96 percent lifetime score from the League of Conservation voters. But he’s been at odds in recent years with more progressive colleagues who want to go further and faster on climate, and snuff out corporate influence on politics. In 2019, he spoke out against a push from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and climate organizers to shun fossil fuel money. As he told WNYC’s Brian Lehrer at the time, “Where do you draw the line? Does that mean that somebody who works for the utility can’t contribute to me?” After a previously chilly relationship with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, his chairmanship has been seen as a means of keeping more left-leaning members at bay since Democrats won the chamber back in 2018.

The nearly 1,000-page CLEAN Future Act Pallone co-sponsored—released in a less ambitious form last year, as an alternative to the Green New Deal—would require power providers to run on clean power by 2035 toward a target of reaching net-zero emissions across the economy by 2050, in line with the Biden administration’s stated goals. But what “clean” means is the subject of some debate: At least for a while, that includes “natural,” or fossil, gas. One central component of the wide-reaching bill is a clean electricity standard that allows for power companies to trade zero-emission electricity credits among themselves to comply with its mandates. Zero-emitting sources are eligible for full credits, but lower-emitting sources—including gas—are eligible for partial credits so long as they fall below carbon-intensity thresholds that will start phasing down in 2030 through 2035. Utilities can make alternative compliance payments, as well, and the Environmental Protection Agency can extend individual companies’ compliance timeline through the 2030s by one year at a time for up to five years total. The measure has been opposed by some 300 climate and social justice groups. “Sacrificing the very definition of ‘clean’ in order to achieve 100 percent clean energy is self-defeating,” the groups wrote in a letter to Congress earlier this month.

Utilities play an odd role in climate politics. Many are finding that transitioning off coal is actually good for their bottom line. Some are now leapfrogging over natural gas entirely, thanks in part to state-level clean electricity standards and the falling cost of renewable power. Still, power companies are eager to navigate any changes to their sector on their own terms and avoid mandates that might force them into compliance. Voluntary commitments to reach net-zero by 2050 have proliferated among utilities over the last few years, but typically still fall well short of what’s needed to meet even the relatively moderate targets pledged by the administration. Like the CLEAN Future Act targets, such promises lean heavily on carbon capture and storage technologies that remain unproven at scale. Electric utility political spending is prolific at the state level, where they regularly buy off regulators and legislators—sometimes literally, as was allegedly the case of Ohio House Speaker Larry Householder. Utility donations aren’t as high-profile as those of major oil and gas companies, despite the two industries having worked together to fund climate denial at the national and international level for decades after their executives first became aware of the threat of global warming.

What might be most remarkable about Pallone’s donations from corporate polluters is just how unremarkable they are in Washington. His office has not responded to a request for comment for this article.