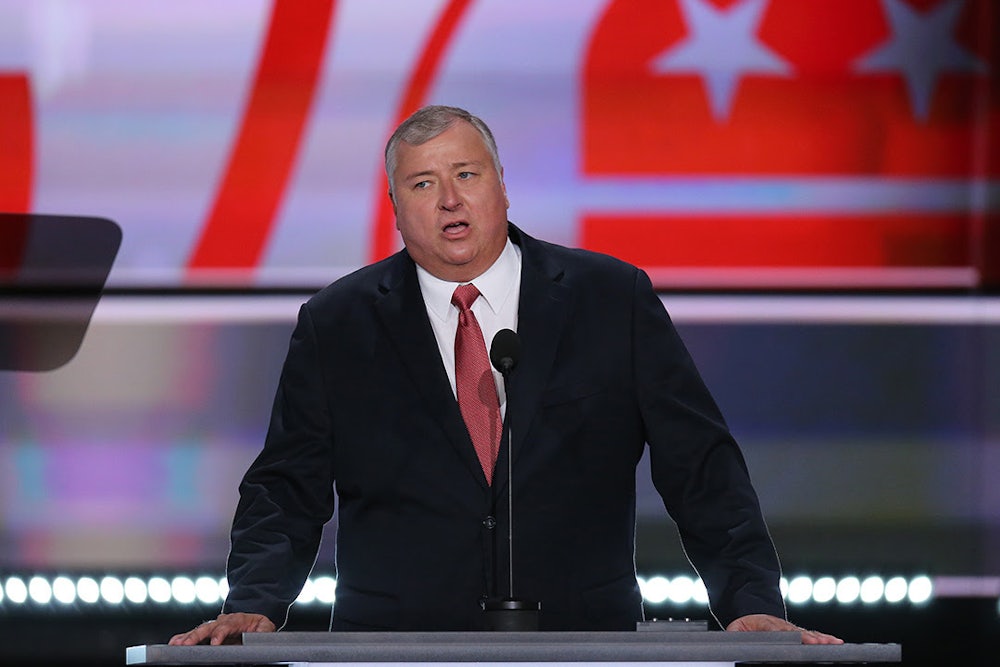

It’s not a great month to be running a utility company. Last week, Ohio Republican House Speaker Larry Householder’s farm was raided as part of an FBI investigation into a $61 million conspiracy between GOP leadership and the utility FirstEnergy to pass a wide-ranging bailout for coal and nuclear plants that also kneecapped the state’s clean energy and energy efficiency measures. In brief, House Bill 6 put Ohioans on the hook for propping up power plants that would otherwise have shut down. In the wake of the arrests, even Republican Governor Mike DeWine is now calling for its repeal.

The details revealed by the FBI’s affidavit this week aren’t an aberration. As political scientist Leah Stokes pointed out this week in Vox, utility cash flows freely through state capitols to battle climate-friendly measures. Even relatively modest lobbying expenditures with state legislatures can yield big wins for fossil fuel interests. Utility watchdogs expect more shoes will drop soon, both on FirstEnergy—which has yet to be formally charged—and its counterparts around the country.

In the past few years, coal interests have grown increasingly desperate to secure their place in a changing state energy landscape. Sometimes, as in Ohio, utilities have coal investments they don’t want to give up. In other cases, the companies that dig coal out of the ground are having trouble getting utilities companies to pay for it. In a recording obtained by The New Republic from the American Legislative Executive Council’s annual summer meeting, Indiana coal companies can be heard angling for another lifeline—albeit in ways less extreme than the criminal process that birthed HB 6 one state over. Its lobbying also hints, however, at a brewing conflict between two industries that have historically found themselves on the same side of the battle against clean energy: “For many decades, the coal mining industry and the coal-burning utilities were aligned over any policy that threatened coal. What you’re hearing in the tape is that divergence,” David Pomerantz, executive director of the utility watchdog Energy Policy Institute, told me.

ALEC is an organization bringing together conservative state legislators and private sector lobbyists. The recording of its Energy, Environment, and Agriculture Task Force meeting, which took place on July 16, offers a rare insight into the shifting politics of energy. The last 20 minutes of the meeting feature a lengthy, near-apoplectic presentation from Matthew Bell, a former Republican state representative in Indiana and founding partner of the political consultancy Catalyst Public Affairs Group. Bell, via Catalyst, has been tapped by Alliance Coal and Sunrise Coal to stop the state from retiring its fleet of coal-fired power plants. The group concedes that customers have good reason to want renewables: “No one would deny today that we work in an evolving energy mix,” Bell said. “Yet data shows us that if we today were to shut down every coal plant in the state of Indiana … we would have the impact of lowering global temperatures over the next 80 years by less than two one-thousandths of one degree. So the goal of an environmentally friendly policy is not appreciably impacted by early retirement of coal plants.” Repeating the same stat later, Bell referred to this impact as “three one-thousandths” of one degree.

But Bell, surprisingly, focused his ire not on radical environmentalists but rather on investor-owned utilities, or IOUs, which, he argued, are doing a disservice to lowly ratepayers by switching from coal, which is mined in Southern Indiana. As coal has grown more expensive relative to natural gas and, more recently, renewables, utilities have begun shifting away from it. Across the country, even some of the most historically intransigent IOUs in Deep Red states are beginning to set net-zero targets to decarbonize their grids, a move that allows them both to get positive press coverage and make money amid shifting economic realities in the power sector.

As the HB 6 battle played out in Ohio last summer, the Northern Indiana Public Service Company, or NIPSCO, announced it would move to get off coal entirely by 2028, replacing it with wind and solar with battery storage at a cumulative savings of $4 billion. That goal was reflected in its Integrated Resource Plan filing with the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission, or IURC, which sets rates of return and profit for power providers and has tended to handle most policy matters related to the state’s electricity industry. Not long afterward, another one of the state’s other major utilities—Vectren Energy—also filed an IRP stating its intention to transition from coal: It now plans to use just 12 percent coal in its energy mix by 2025.

“It’s not like the regulators there are environmental heroes. They just couldn’t justify keeping that plant online,” Pomerantz said of recent developments in Indiana. The story is similar, he said, for the utility companies. “They’re all going to profit. They get to rate-base all those renewables. Profit is just better for them on renewables than for gas because it’s all capital expenditure,” whereas gas infrastructure requires them to purchase a continual supply of fuel.

Bell, in the meeting, complained about IOUs’ hypocrisy on renewables: “Those same investor-owned utilities who talk about being carbon neutral suggest that it’s important to build a natural gas plant in Indiana to bridge the gap, with the hope of retiring that plant early and deploying a new green technology at some point in the future. The ratepayer pays every time that construction occurs,” he said. He’s got a point—natural gas is unsustainable and greenhouse gas–intensive, and building out new gas-fired power plants and associated infrastructure now will lock in emissions for decades to come. But that’s not the whole story of what’s happening in Indiana or what’s irking his clients.

As Bell mentioned at the start of his talk, energy prices have indeed skyrocketed over the last several years, but not because utilities have begun moving away from coal, as he suggests. “We spent $13 billion propping up these old coal plants. That’s why bills in Indiana have increased,” said Kerwin Olson, executive director of Indiana’s Citizen Action Coalition, which has worked on energy and utility issues in the state since the 1970s. The costs of keeping those coal plants online have been passed down to consumers and prompted several of the state’s utilities to move to new sources of energy. “The great irony here is that it is the utility companies shutting down these coal plants based on sheer economics. It isn’t because of the CAC or the Sierra Club,” said Olson. Recently, the CAC has worked with an odd-bedfellows coalition, including environmentalists, the Chamber of Commerce, and IOUs to fight off a proposal by the coal industry to put a new temporary moratorium on the construction of electric generation capacity over 250 megawatts, leaving utilities to stick with their existing coal fleets.

Coal companies weren’t too happy about the defeat. “When NIPSCO filed that IRP, that shook the ground,” Olson said. “We’ve seen a lot of coal come offline in Indiana. We’re seeing a lot of proposed coal retirements because of cost to customers.” Since then, coal money has flowed into Indianapolis to push through a series of coal-friendly measures, including an HB 6-style bailout called HB 1414; former Trump EPA head Scott Pruitt, who resigned amid a torrent of ethics and management scandals, is now registered as a lobbyist there. And while CAC and its allies fought off the moratorium, they didn’t manage to prevent the creation of a 21st Century Energy Policy Development Task Force, which Bell praised on the call. Composed of a bipartisan group of state lawmakers and experts appointed by Governor Eric Holcomb, who has close ties to the state’s coal industry, the task force has met five times so far and is due to deliver its recommendations to the governor and the legislature by December 1. Olson suspects the task force will seek to create an alternative to the IRP process that will be more amenable to coal than either utilities or state regulators in the IURC. “The bottom line is that the coal interests want to get rid of that IRP process. Why? Because now the IRP process is a public and transparent process that allows people like my organization to participate, hire experts, and criticize its inputs and outputs,” he said.

Predictably, then, Bell criticized state regulators in his remarks. “They were made to be a rate-setting body,” Bell told ALEC members of the IURC. “They were not made to be a policymaking body. Yet more and more when utilities present integrated resource plans and accelerated depreciation, they are in effect setting policy. The legislature has ceded that power to the regulatory commission, and in doing so left the ratepayer without an incredibly important advocate. I want to encourage you as policymakers to reclaim that responsibility that is yours,” he concluded. The 21st Century Energy Policy Development Task Force is presumably one such model for wresting power from regulators.

Maneuvering for task forces and bailouts is a far cry from the salad days of King Coal. But the industry remains a potent political force, and as the last few years in Ohio and Indiana show, coal won’t go down without a fight. “It’s the last dying gasps of the coal industry,” Pomerantz told me. “They like this storytelling better when they get to say they’re fighting the crazy radical hippies, but at this point, they’re fighting the utilities. There’s no loyalty left in the investor-owned utilities for coal.”

This all puts the Edison Electric Institute—the trade association for investor-owned electric utilities—in an awkward spot, both on calls like the one July 16 and in coalitions like ALEC, which have historically been a united front on fossil fuel boosterism. Helping to host the ALEC webinar was Jennifer Jura, private sector chair of ALEC’s Energy, Environment and Agriculture Task Force and director of external affairs for EEI. Some of her members are still fighting renewables, but a growing number are spurning their traditional allies in the coal industry by switching over to other fuel sources, for reasons having nothing to do with idealism.

Like ExxonMobil and other fossil fuel interests, EEI funded climate denial through the 1990s despite knowing full well the reality of the threat posed by rising temperatures. Also like various fossil fuel companies, it has made a show in the last few years of its commitment to decarbonization. The group has shown up in force at gatherings like annual U.N. Framework Conventions on Climate Change meetings to “tell the U.S. electric power industry’s story of clean energy leadership,” despite its members still battling clean energy measures at home. The current director of climate programs for EEI, Eric Holdsworth, previously served nine years as the deputy director of the Global Climate Coalition, a group funded by fossil fuel companies and other business interests to undermine U.S. participation in the Kyoto Protocol through disinformation campaigns casting doubt on the scientific consensus about climate change.

Whatever this brave new world of climate policy will look like, coal and old-school climate deniers are getting left behind. “Outside of a couple kooks in the Trump administration, there’s really no place left where you can go full climate denial and be taken seriously. If there is one it would be ALEC, but even that has changed,” said Pomerantz. “That part of the conversation is basically over.”

A previous version of this article misstated the capital of Indiana.