No piece of Covid-era filmmaking has been praised quite as much as the 13-minute montage that opened the second impeachment trial of Donald Trump. CNN’s Chris Cillizza argued that it was “unfathomable that any senator—Republican or Democrat—could watch that 13-minute video and not be changed by it.” The Washington Post’s Margaret Sullivan noted that “every second seemed as terrifying as the day it was recorded. More so, in fact.” MSNBC’s Chris Hayes opened his television show by playing it in its entirety.

It is undoubtedly a powerful piece of filmmaking (as was the video, never before seen, that was featured on the second day of the trial). Consisting of footage captured by security cameras, cell phones, and uncharacteristically frightened television cameramen, the video distilled the events of January 6 into a concise and harrowing narrative: A mob, spurred on by the president, attacked the Capitol and came astonishingly close to harming or even killing members of Congress and members of the executive branch. It provided an irrefutable account of the president’s role in an event that left seven dead and threatened the peaceful transition of power.

The video was so damning that it short-circuited political reporters’ hard-wired impulse to equivocate, water down, and, above all, hear both sides. The visual evidence on display—aided, it should be added, by the incompetent performance of Trump’s defense attorneys—made the Republican case irrelevant. How could they compete with such stirring documentary evidence? The video got such rave reviews that it would surely have a 100 percent fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes had it been given a theatrical release. Trump’s own impeachment lawyers praised it during their opening statements. Even Steve Bannon was impressed!

The video was so convincing, however, that it led reporters and analysts into some erroneous historical revisionism. The second impeachment trial is an open-and-shut case, they said; the first one, not so much. The truth was that the first impeachment trial was also open-and-shut, and the fact that it is no longer seen as such reveals the extent to which the Republican narrative continues to dominate coverage of Washington.

Writing in Mother Jones before the proceedings, for example, David Corn argued that the first impeachment was “much like a prosecutor attempting to nab a crime boss by concentrating on a single illegal act for which the proof was rock-solid,” but that “Trump was not impeached for his overall assault on the rule of law” as was happening in Impeachment Part Two. The New York Times’ resident conventional-wisdom generator, Peter Baker, meanwhile, made the case that the big problem with Impeachment Part One was that the case against Trump was too “abstract.”

This was no phone call transcript, no dry words on a page open to interpretation. This was a horde of extremists pushing over barricades and beating police officers. This was a mob smashing windows and pounding on doors. This was a mass of marauders setting up a gallows and shouting, “Take the building!” and “Fight for Trump!” …

Where the case against Mr. Trump a year ago turned on what might have seemed like an abstract or narrow argument about his behind-the-scenes interactions with a far-off country, Ukraine, the case this year turns on an eruption of violence that Americans saw on television with their own eyes—and that the senators serving as jurors experienced personally when they fled for their lives.

There is a correct (if somewhat crass) argument here: The assault on the government that Trump instigated was so visceral, so violent, that it could not be denied, whereas no one was literally hurt by the actions that led to his first impeachment. But there is nevertheless an astonishing amount of memory-holing on display here.

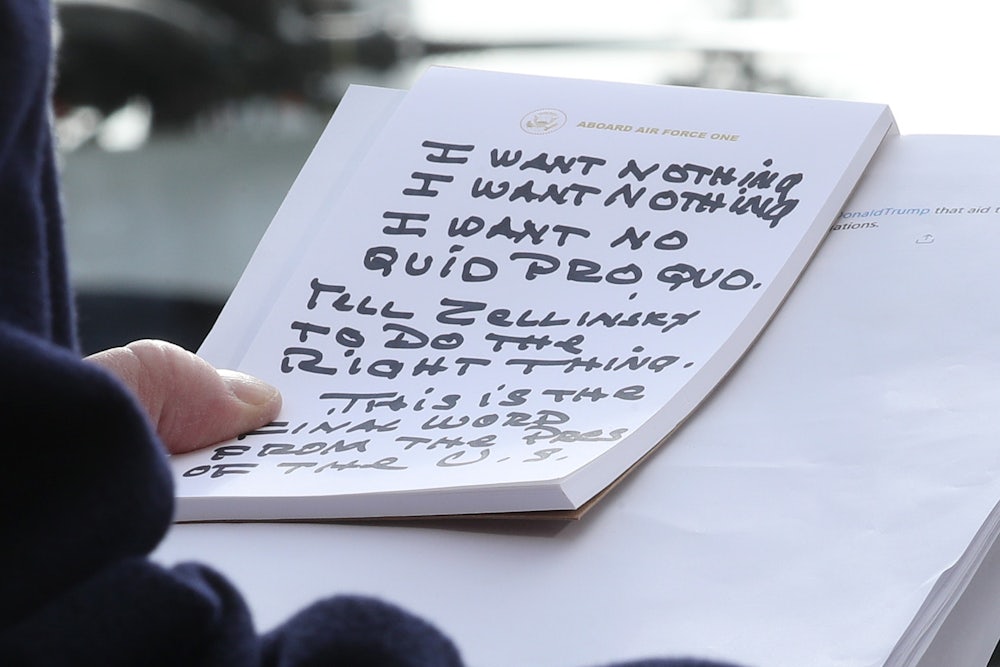

There was nothing “dry” or “open to interpretation” about the transcript that led to Trump’s first impeachment. That transcript depicted the president of the United States threatening to withhold aid to a smaller country unless it opened a frivolous investigation into his most dangerous political rival. Yes, Trump had committed a great number of possibly impeachable offenses prior to that phone call, but Democrats chose to focus on this offense for two reasons: One was that it was open-and-shut in ways that other cases were not, and the other was that it captured Trump’s assault on the rule of law and American democracy.

And while the Democrats did not have anything like the 13-minute video that was played on Tuesday, it did have bombshell testimony from a number of players—Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, Fiona Hill, the Trumpian Gordon Sondland—that made for what the media would consider “good television.”

There was nothing “abstract” about this trial. Here was a president caught in the act of trying to get a foreign government to interfere with a U.S. election. That this is essentially being treated as analogous to busting Al Capone on charges of tax evasion—nothing could be further from the truth.

This revisionism stems from Trump’s success at muddying the waters and from efforts by Republicans and conservative media to downplay the seriousness of Trump’s infractions. They were successful in that effort, not only getting Trump acquitted but convincing the press to remember the controversy as a typical partisan conflict. Democrats say he did something wrong, but Republicans disagree. How will we ever figure out what really happened?

All it takes, apparently, to break this approach to politics is compelling, irrefutable video evidence. But this standard leaves nearly all that takes place in politics up for debate—it also makes the standard of an impeachable offense impossibly high. “Compelling, violent visuals can be brilliant at communicating the truth, but they shouldn’t be necessary to that end,” writes Jon Allsop in Columbia Journalism Review. The result is a situation in which Trump’s many outrageous actions—including the ones that got him impeached two years ago—are all but excused because they pale in comparison to a violent assault on the Capitol.

The video showed by Democrats on day one of the second impeachment trial broke the “objective” reporter’s studied refusal to admit what was in front of his nose. But it also revealed the remarkably high bar required to get reporters to acknowledge basic reality.