Three years before he died at 75 in 2015, Julian Bond sat down for an interview on his life and work. Asked how he would like to be remembered, Bond replied, with his characteristic alloy of amiable candor and laconic wit:

I want a double-sided headstone. On one side, I want it to say, “Race Man” and that means a man who doesn’t dislike other races, but who’s proud of his own and wants to lift it up. The other side is going to say, “Easily Amused.”

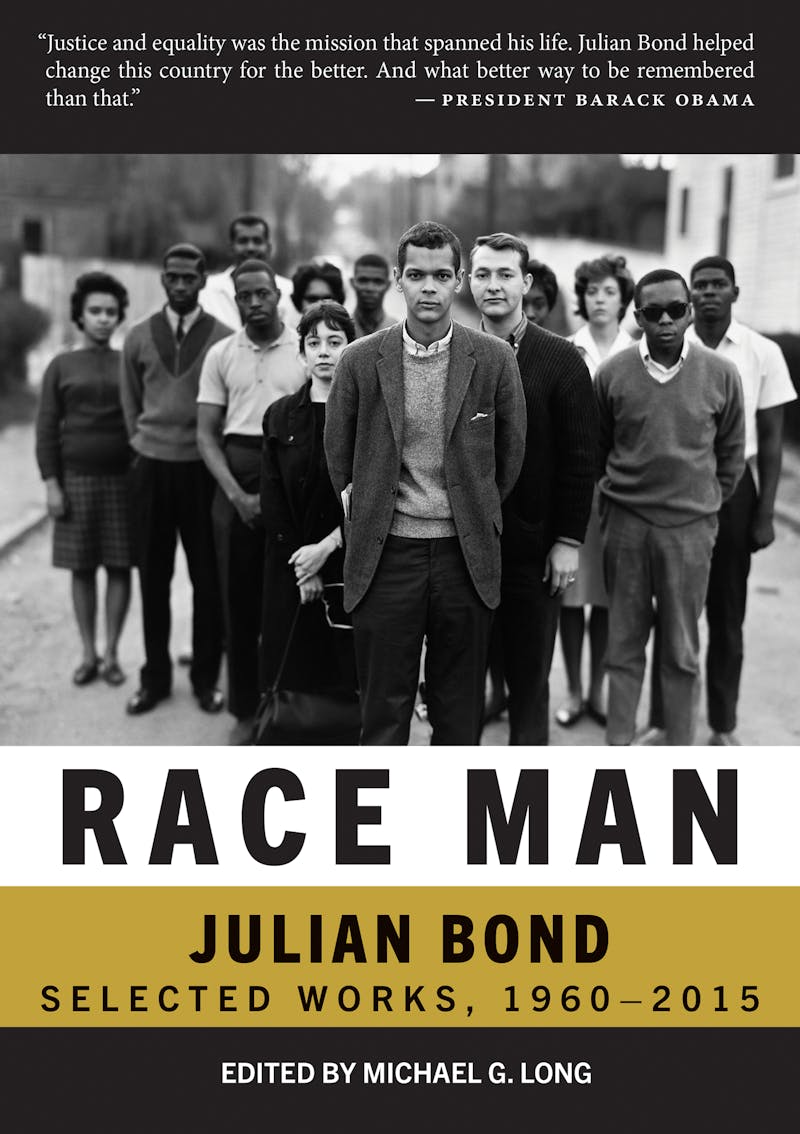

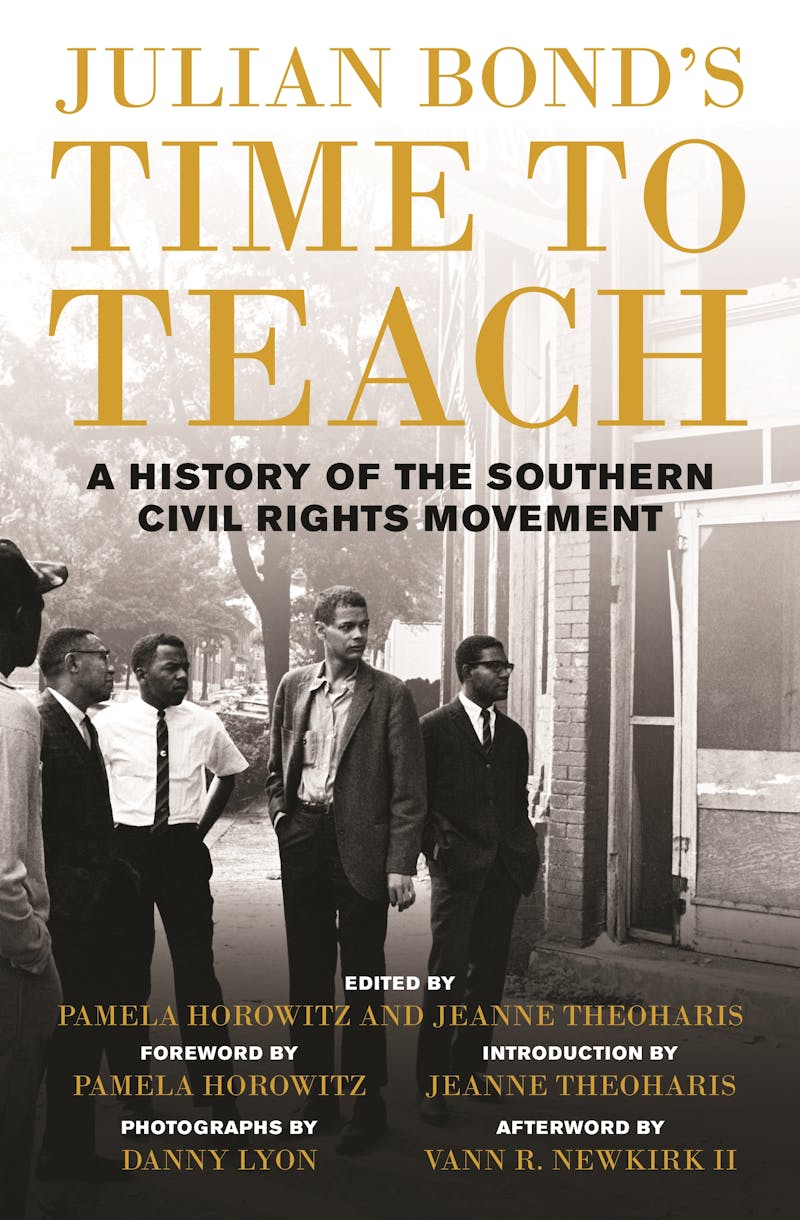

The first side of Bond comes through in two new collections of his writing: Race Man—a volume of Bond’s speeches, op-ed columns, interviews, and autobiographical essays—and Julian Bond’s Time to Teach, a narrative history of the Southern civil rights movement assembled from lectures Bond delivered at the University of Virginia, Harvard, and other schools. Among the fabled activists who risked their lives and transformed those of many others in the civil rights movement, Bond stood out with his smooth patter, winsome charm, and understated glamour. While his writings alone can’t completely evoke that variegated image, they remind us what he and others of that insurgent generation meant to America: The Bond that emerges from these books is a complex, fascinating presence, whose expansive intellect and sociopolitical commitment gave activists and students a model to adopt, and adapt, as their own.

Yet the lessons from his career are far from straightforward. Neither of the new books deals with the vexing question of how or why so many great expectations for Bond went unfulfilled. Even now, whenever his name comes up among those who were alive and politically aware during the twentieth century’s second half, they wonder how someone so telegenic, witty, and skilled in the mechanics of political life never ascended to higher office. How had Bond, who’d seemed better placed to attain national prominence than any African American politician of his generation, never risen to a position in federal government? Among political leaders of similar promise and magnetism in the same era, perhaps only Mario Cuomo matches Bond in the cumulative swirl of “what-ifs” and “why-nots” around their respective paths.

To make sense of Bond’s legacy, the “easily amused” side of him is just as important. As a public figure, his greatest strength may have been his ability to persuade his followers, radical and non-radical alike, to think and act outside their respective comfort zones. He believed contradictory things could be true without canceling each other out, and if he didn’t seem bothered or weighed down by paradox, it may be because he believed being reasonable was more important than being doctrinaire. He was, fundamentally, a humanist, and sometimes the only option a humanist has is to be “easily amused” with people’s frailties. To many now angered by up-to-the-minute injustice and folly, this may be too weighty a contradiction to carry around. Julian Bond made it look easy without compromise or capitulation. He may have been on to something.

Bond was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1940. The son of an eminent scholar, he seemed fated to spend his whole life in academia. His father, Horace Mann Bond, became president of historically Black Lincoln University in Chester County, Pennsylvania, when Julian was five years old, and the younger Bond attended George School, a local Quaker prep school. The tenets of nonviolence and collective decision-making taught there left a lasting impression on Bond, as did his father’s insistence that education was to be used to help those most in need. Like other Black teenagers of his generation, Bond was emotionally affected and politically awakened by the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi in 1955. “It terrified the 15-year-old me,” he recalled. “I asked myself, ‘If they will do that to him, what won’t they do to me?’”

At Morehouse College in Atlanta, he took a philosophy course taught by Martin Luther King Jr. In early 1960, as he later (and often) recalled it, his Morehouse classmate Lonnie King Jr. showed Bond a newspaper article about Black students at Greensboro’s North Carolina A&T State University staging a “sit-in” at the whites-only lunch counter at the local Woolworth’s. King asked Bond if he thought this was the sort of thing that could happen here, and Bond replied by saying it should and would sooner or later. King, as Bond recalled, then said, “Why don’t we make it happen here?” In other accounts, Bond says the riposte “What do you mean we?” froze in his throat before they both were recruiting other students at the schools comprising the historically Black Atlanta University Center to forge their own passive resistance assault on Atlanta lunch counters. “Within a few weeks,” Bond recalled, “77 of us had been arrested.”

By April 1960, the legendary activist Ella Baker encouraged Black student movements throughout the South to form an organization of “nonviolent direct action” independent of established civil rights groups. Hence, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee came into being. Bond, with characteristic self-deprecation, often referred to himself in those years as primarily an “office functionary” for SNCC, working mostly as the group’s publicist, writer, or press relations specialist. He’d also cultivated a literary bent in those years, publishing poetry in SNCC publications and elsewhere. Perhaps his most lasting achievement as a poet, which for some reason isn’t included in Race Man, was this gnomic couplet:

Look at that girl shake that thing

We can’t all be Martin Luther King.

It was in these and other writings that Bond’s droll humor surfaced and would over time become part of his appeal, along with his good looks, serene composure, and verbal fluency.

Someone like that, activists reasoned, should go into politics. And when a new, predominantly Black legislative district was created in Atlanta, Bond’s friends, including SNCC’s chairman, John Lewis, urged Bond to pursue the vacant seat. SNCC marshaled its forces for door-to-door campaigning throughout the district, and Bond handily won in 1965, with 82 percent of the vote. The following January, when Bond turned 26, the Georgia House of Representatives denied him his seat by a 184–12 vote because he came out in support of a SNCC resolution opposing the Vietnam War. The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that December that the Georgia House had denied Bond his First Amendment rights, and it was required to seat him.

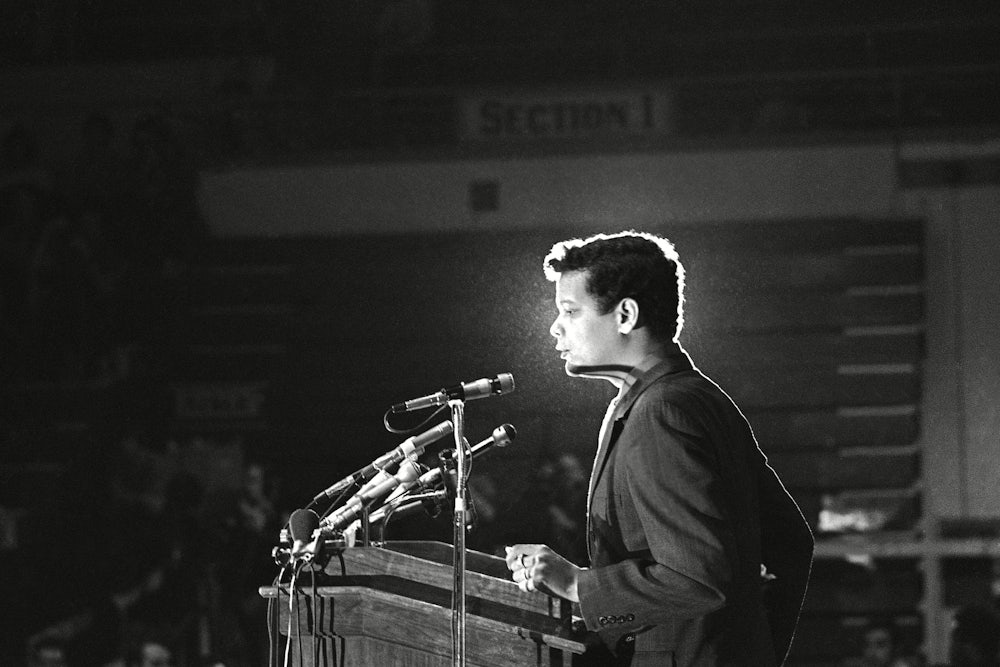

The furor gave him national renown, and two years later, at the roiling 1968 Democratic National Convention, he helped lead a racially integrated group of progressive Georgia Democrats opposing the state’s delegation, led by segregationist Governor Lester Maddox. Bond seconded the nomination of anti–Vietnam War politician Eugene McCarthy as the party’s presidential candidate. In a challenge to establishment Democrats, Wisconsin delegate Ted Warshafsky even nominated Bond for vice president. During the subsequent roll-call vote, Bond withdrew his name from consideration because, at 28, he was seven years below the constitutionally required age minimum for executive office. “He had done this,” reported Norman Mailer, “with the sort of fine-humored presence which speaks of future victories of no mean stature.”

It is difficult to overstate how, in the immediate afterglow of his emergence in Chicago, Julian Bond assumed an aura approaching rock-star magnitude. I remember covering—or trying to cover—for my high school newspaper a speech he gave at Hartford’s Trinity College in the fall of ’68, where the crowd spilled so far out of the lecture hall that loudspeakers were hastily installed in the corridors. The emotions he aroused were painfully easy to account for: In the aftermath of the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, Bond appeared to their bereft followers to be a tousled amalgam of King’s frontline civil rights credibility and Kennedy’s diffident, boyish charm. Journalist Marshall Frady, in a profile of Bond published the year before in The Saturday Evening Post, neatly captured Bond’s physical presence at the time: “tall, willowy, almost wraithlike, with a quiet and finely modulated voice textured, it seemed, of flannel.”

Bond sustained this supernal aura well into the next decade, with more lectures throughout the country, regular radio commentary, and numerous television appearances (including a hosting gig on Saturday Night Live that gave his easy-does-it drollness ample space to roam), all the while advancing from the Georgia House to its state Senate. Even from this modest platform, Bond’s positions assumed greater dimension and drive; he attacked not only white supremacy and institutional racism, but also sexism, South African apartheid, and the Republican right’s reactionary worldview. His tours of college campuses in the 1970s yielded the dispiriting sight of diminishing student activism. “Perhaps,” he’d reflected, “the time will come when the campus will be a center for social change and protest—for the moment, it has reverted to being a factory for social certification.”

Bond’s fellow Georgia Democrat, Jimmy Carter, would not be spared his disdain. Unlike other notable Black Atlantans, such as Mayor Maynard Jackson and King’s deputy (and future U.N. Ambassador) Andrew Young, Bond didn’t support Carter’s bid for the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination, citing the onetime Georgia governor’s retrograde, if later-renounced, views on the Voting Rights Act. Even after Carter became president, Bond kept the pressure on; a frequent riff in his late 1970s speeches jibes that Carter “may know the words to our hymns, but not the numbers on our paychecks,” in reference to the president’s anti-inflation policies that Bond claimed were hurting the poor and minorities.

By the time Carter had been inaugurated in 1977, Julian Bond might well have been the most famous state legislator in America. If there’s little in Race Man that delves into his workaday legislative record in those years, it may be partly because his celebrity at the time was so much larger than his office. He could have been, in anybody’s universe, a man of letters, a politician, a television host, even a movie actor and was, at various times of his life, all of these, though only through the most generous indulgence could you consider his bow-tied cameo in Greased Lightning an auspicious foundation of a big-screen career. Not that he ever wanted such a thing. He certainly didn’t need it, preferring to lend his textured, flannel voice to such tasks as narrating Eyes on the Prize, the epochal 14-part documentary about the civil rights movement, whose installments ran in 1987 and continued in 1990.

Still, the higher Bond’s public profile rose, the more Mailer’s expectations of “future victories” seemed to recede. He’d considered his own presidential run in 1976 (he was by then 36), first as a Democrat and then as an independent nominee of the National Black Political Convention. He was “flattered, but didn’t want the responsibility of running for president while trying to get reelected to the Georgia State Senate.” However much history had induced the reserved, scholarly son of Horace Mann Bond to devote his life to social and political activism, Bond’s career in electoral politics disclosed a reticence that belied the most extravagant hopes for his future. As far back as 1967, Marshall Frady observed that, in contrast with Lewis, James Forman, Stokely Carmichael, and other SNCC leaders, Bond “usually seemed … to have a difficult time taking himself or his situation seriously. He more suggested one of those languid, leisurely, bright, introspective and exquisitely detached young men in Henry James novels, always preferring to dwell on the periphery of passionate events and conflicts.”

By the mid-1980s, ascension to the national office for which he’d so long seemed destined appeared within his grasp. He ran for Congress in 1986 as a representative for Georgia’s majority Black 5th Congressional District, which Bond helped establish through his own efforts as a state senator. But the August primary for the Democratic nomination yielded inconclusive results. Bond and his friend and SNCC comrade John Lewis entered into a brutal and, to friends of both men, heartbreaking runoff campaign. Lewis depicted his onetime colleague on the groundbreaking 1970s Voter Education Project as lackadaisical and out of touch with the concerns of the district’s residents. Bond was even more taken aback when Lewis demanded that his old friend take a drug test. Bond adamantly refused, he insisted, as a matter of principle; he’d bristled just as much 20 years before, when, during the furor over losing his state representative’s seat, a reporter asked whether he was a communist. Bond said no, but angrily added that he would never answer such a question again. “I resent it. It implies that I don’t have the intelligence to arrive at the position I have taken without having been manipulated by someone else.”

When the votes were counted in the 5th District race, Lewis received 34,548 to Bond’s 32,170. Bond’s close friendship with Lewis was damaged beyond repair. (“We see each other from time to time,” Bond said in a 2002 interview, “and I would like to think we’re cordial. But it has never healed.”) Bond’s wife, Alice, whom he’d married in 1961 when both were college students, made the drug use rumors public after the election, with allegations that he’d used cocaine supplied by a woman with whom he’d allegedly had an affair. She later retracted the charges, but she and Bond separated in 1987 and divorced two years later. As Bond’s marriage unraveled, so did his reputation in Atlanta, where he’d lived, gone to school, raised a family, and served in the state legislature for two decades. He left for Washington, D.C., because, as he told an interviewer years later, Atlanta “had become not a happy place for me. It was a place I didn’t want to live anymore.”

More than anything, the congressional loss marked the melancholy end to what once seemed to be an incandescent political destiny. The dynamic impression Bond made on that Chicago convention floor in 1968 convinced many Americans at the time that if anybody was destined to be the nation’s first Black president, it was Horace Julian Bond. And while from the late 1980s till his death, his fame endured as a television personality, NAACP chairman, emeritus leader of the Southern Poverty Law Center (which he helped found in 1971), and a teacher and movement historian, his political career would resound as a cautionary tale of unfulfilled promise and squandered opportunities, just as John Lewis had ruefully declared. “I love Julian like a brother,” Lewis said. “But he fumbled the ball. He had unbelievable opportunities. He just didn’t take advantage.”

There is, however, nothing unfocused or lackadaisical about the sensibility behind Race Man or Time to Teach. The polemics in the former are charged with an impassioned, often acerbic impulse to challenge hidebound dogma and reactionary thinking wherever he found it. He came down as hard on Louis Farrakhan (“a black Pat Buchanan or David Duke,” whose “vision of black Americans as pathologically unsuited for citizenship has its parallels in the most racist diatribes of white supremacists”) as he did on Jimmy Carter. He took seriously his reputation as a “race man,” but his expansive view of human liberation took in far more than Black America. In response to criticism, even from the Black community, that gay rights were in no way analogous to civil rights for racial minorities, Bond insisted that “gay and lesbian rights are not ‘special rights’ in any way. It isn’t ‘special’ to be free from discrimination—it is an ordinary, universal entitlement of citizenship.” On the other hand, he rejected analogies of the civil rights movement to the anti-abortion “Operation Rescue” protests:

The civil rights demonstrators faced taunts and threats. Today’s antiabortionists taunt and threaten those who brave their picket lines. The civil rights movement fought for the right to cast a vote. The antiabortionists want to cast women’s votes for them.

Teaching took up much of Bond’s life in the 30-plus–year aftermath of his political career, and you can understand while reading Time to Teach why his history courses were so popular. His lectures were both concise and thorough in rendering the transfiguring events of the 1960s with just enough prologue about the movement’s origins in post–World War II America and its complex pathways through American life up to King’s 1968 assassination. He weaves his own memories into the narrative, always pertinently. He recalls visiting the ruins of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church with Lewis and other SNCC members on the afternoon the church bombing killed four young girls. “The bombing confirmed the ineffectiveness of nonviolence for many and relegated it to tactical use alone for many more, rather than a way of life. And it underscored the need for political power.” (My italics.)

Bond believed it was possible to bring radical aspirations to non-radical processes, to contain one’s expectations without compromising one’s integrity. In an appearance Bond and Lewis made in 1974 on William F. Buckley Jr.’s Firing Line, they spoke with the conservative gadfly about such issues as Black voter registration and the efficacy of “getting things done” for the Black community within the political process. With urbanity that matches his interlocuter’s, Bond analyzes Black political power, locally and nationally, as applied to such issues as housing, employment, and economic development. At one point, as if the discourse is reaching into the present moment, the issue of excessive police violence against Black citizens in Atlanta is introduced into the discussion, with Bond insisting that neither he nor Lewis argue that just because more Black people vote, in the South and elsewhere, that gratuitous police shootings of Black people will stop.

Nevertheless, as an example of how some things could change the political or social equation, Bond tells the story of a visit he and Lewis made to an Alabama town to speak at a meeting of Black residents. Outside, he tells Buckley, there was a Black man beating his wife with a shotgun. When a sheriff arrived on the scene, the man pointed a shotgun at him, and the sheriff said, “Brother man, give me that gun,” which the man then did.

BOND: Now I don’t know if this sheriff’s predecessor would have done it differently. He might have shot the man, or he might have called in his deputies and had them surround him or something.… But he said, “Brother man, give me that gun.”

BUCKLEY: Did the woman survive?

BOND: Oh yes … and the man who beat her survived, too, and the sheriff survived. So I think the political process does change those kinds of things. It doesn’t guarantee [change]. It never has, for any group of people in this country. It’s never guaranteed instant anything.

To those impatient for change, especially now, this may sound like undue moderation, or, worse, capitulation. But Bond’s equanimity toward the push-pull transactions of democracy seamlessly coexisted with his unyielding indignation toward injustice in all its forms. He set a template for future activism that can be both skeptical and assertive, measured and combative, pragmatic and progressive.

So what if he didn’t make it beyond the Georgia state Capitol himself? When the crucial do-over of last fall’s dual U.S. Senate elections in Georgia came down to the wire in January, one of the regions deciding whether Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff would win their seats, and thus alter the Senate’s Republican majority and provide the state with its first two Democratic senators in a generation, was the 5th Congressional District in Fulton and DeKalb counties—the district Julian Bond helped create almost 40 years before. He didn’t win that seat as he’d hoped. But sometimes you don’t have to get what you want, or what others believe you should have, in order to change America. You don’t even have to be around to see it happen.